Church and State in Dutch Formosa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Calvinism in the Context of the Afrikaner Nationalist Ideology

ASIAN AND AFRICAN STUDIES, 78, 2009, 2, 305-323 CALVINISM IN THE CONTEXT OF THE AFRIKANER NATIONALIST IDEOLOGY Jela D o bo šo vá Institute of Oriental Studies, Slovak Academy of Sciences, Klemensova 19, 813 64 Bratislava, Slovakia [email protected] Calvinism was a part of the mythic history of Afrikaners; however, it was only a specific interpretation of history that made it a part of the ideology of the Afrikaner nationalists. Calvinism came to South Africa with the first Dutch settlers. There is no historical evidence that indicates that the first settlers were deeply religious, but they were worshippers in the Nederlands Hervormde Kerk (Dutch Reformed Church), which was the only church permitted in the region until 1778. After almost 200 years, Afrikaner nationalism developed and connected itself with Calvinism. This happened due to the theoretical and ideological approach of S. J.du Toit and a man referred to as its ‘creator’, Paul Kruger. The ideology was highly influenced by historical developments in the Netherlands in the late 19th century and by the spread of neo-Calvinism and Christian nationalism there. It is no accident, then, that it was during the 19th century when the mythic history of South Africa itself developed and that Calvinism would play such a prominent role in it. It became the first religion of the Afrikaners, a distinguishing factor in the multicultural and multiethnic society that existed there at the time. It legitimised early thoughts of a segregationist policy and was misused for political intentions. Key words: Afrikaner, Afrikaner nationalism, Calvinism, neo-Calvinism, Christian nationalism, segregation, apartheid, South Africa, Great Trek, mythic history, Nazi regime, racial theories Calvinism came to South Africa in 1652, but there is no historical evidence that the settlers who came there at that time were Calvinists. -

The First Episode of Formosa Church: Robertus Junius (1629-1643)

The First Episode of Formosa Church: Robertus Junius (1629-1643) The First Episode of Formosa Church: Robertus Junius (1629-1643) Lin Changhua(林昌華) 荷蘭阿姆斯特丹自由大學 神學研究所哲學博士 本院歷史學教授 摘要 尤羅伯牧師(1629-1643)為荷蘭改革宗教會派駐台灣宣教師當中,成果最為豐碩 的一位。他在 1606 年誕生於充滿自由和寬容思想的鹿特丹市,在 19 歲時進入萊登大 學當中,專門為培養服事於東印度地區的「印度學院」(Seminarium Indicum)就讀畢 業之後經由鹿特丹中會派遣,前往東印度地區服事,他在 1629 年來到福爾摩沙。在 1643 年時約滿回歸祖國。歸國後在台夫特(Delft)教會服事一段時間,後來前往阿姆 斯特丹教會,他在該城設立一間專門訓練前往東印度神職人員的訓練學校。在台灣 14 年的服事期間,建立教會,為 5400 人洗禮,並且設立學校教導原住民孩童,也設立 一間「師資訓練班」栽培 50 名原住民作為小學校的師資。荷蘭人來到台灣以前,西 拉雅原住民有強制墮胎的習俗,這樣的風俗可能是千百年來流傳下來的風俗,原住民 本身不以為意。但是,對宣教師來講,殺害無辜嬰孩的行為是干犯《十誡》的嚴重罪 行,不是歸咎於風俗習慣就可以視而不見。於是尤羅伯牧師認為要解決這個問題,必 須雙管齊下,首先是透過行政的力量阻止西拉雅的女祭司繼續進行殺嬰的行為,再來 透過教育的方法,編撰相關的教理問答,讓原住民改掉這個風俗習慣,而他所編撰的 教理問答也可以算是荷蘭教會「脈絡化神學」(contextual theology)在台灣的實現。由 131 玉山神學院學報第二十四期 Yu-Shan Theological Journal No.24 於在台灣的宣教成果極為卓著,因此在 1650 年代的英國有人撰寫一本小書讚揚他為 5900 人洗禮的偉大成果,而台灣的宣教也成為荷蘭改革宗教會在東印度地區宣教的模 範。 Keywords: Dutch East India Company, catechisms, contextualization, Zeelandia 132 The First Episode of Formosa Church: Robertus Junius (1629-1643) In 1624, Dutch East India Company1 established a colony in Formosa, at the same time Christian clergymen start their service in the island thus mark the genesis of Formosan church. During East India Company’s administration in the island from 1624 till 1662, more than 30 ministers came to served there. Amongst them, the greatest missionary of Dutch Reformed Church was Rev. Robertus Junius. He was not the first minister served in Formosa, however due to missionary zeal as well as linguistic talent, he was able to baptized 5400 native inhabitants, established schools for Formosan children and youth during his 14 years of service in Formosa. Beside these establishments, Junius also compiled several contextualized versions of Formosan catechisms to teach native Christian, and his method can be defined as the first contextualization endeavor in Taiwan church history, a significant step for Taiwan theological reflection. -

Missionary History of the Dutch Reformed Church

Page 1 of 2 Book Review Missionary history of the Dutch Reformed Church Being missionary, being human is a must, especially for those with an interest in missiology. It not Book Title: Being missionary, being only provides a fresh perspective on the missionary history of the Dutch Reformed Church (DRC) human in South Africa, it also provides a clear description of the interactive relationship between context and mission. The author is a respected missiologist who is also well acquainted with the history of Book Cover: mission in the Southern African context. His method of research can be termed an interdisciplinary approach of interaction between culture, religion, and political economy. He describes the social history in terms of waves of change. His intention is to describe the periods he distinguishes as waves, because this specific term makes good sense when describing the periods of extraordinary mission endeavor. The first wave describes the period, 1779−1834. In what he calls ’a reflection on the early Dutch Reformed Mission’, he describes the period that falls in the framework of the freeing of the slaves, Author: as well as the development of a colonial society in the Cape Colony. This is also the period of Willem A. Saayman mission-awakening in the protestant churches of Europe. It was during this time that Van Lier and Vos had established a ministry with far-reaching consequences in the Cape Colony. Both these ISBN: ministers cultivated a much greater sense of mission involvement amongst the free-burghers in the 9781875053650 Colony. During this period the focus of mission work was mostly directed towards the slaves – a Publisher: group that was not only subjected to the worst possible human brutalities and dehumanisation, but Cluster, Pietermaritzburg, was also regarded as non-Christian. -

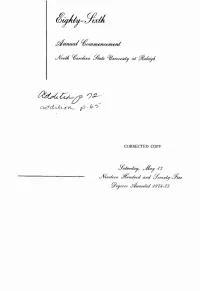

Mmum/ . CORRECTED COPY

Mmum/ . CORRECTED COPY DEGREES CONFERRED A CORRECTED ISSUE OF UNDERGRADUATE AND GRADUATE DEGREES INCLUDING DEGREES AWARDED JUNE 25, 1974, AUGUST 7, 1974, DECEMBER 18, 1974, AND MAY 17, 1975. Musical Program EXERCISES OF GRADUATION May 17, 1975 CARILLON CONCERT: 8:30 AM. The Memorial Tower Nancy Ridenhour, Carillonneur COMMENCEMENT BAND CONCERT: 8:45 A.M. William Neal Reynolds Coliseum ”The Impresario”, Overture Mozart First Suite in Eb ..........................................................................................Holst l. Chaconne 2. Intermezzo 3. March 1812 Overture ....................................................................................Tchaikovsky PROCESSIONAL: 9:15 AM. March Processional ..............................................................................Grundman RECESSIONAL: University Grand March Goldman NORTH CAROLINA STATE UNIVERSITY COMMENCEMENT BAND Donald B. Adoock, Conductor Marshals provided by Alpha Phi Omega, Blue Key, Golden Chain and Golden Theta Delta Ushers provided by Arnold Air Society and Angel Flight The Alma Mater Words by: Music by: ALVIN M. FOUNTAIN, ’23 BONNIE F. NORRIS, ]R., ’23 Where the winds of Dixie softly blow o’er the fields of Caroline, There stands ever cherished N. C. State, as thy honored shrine. So lift your voices! Loudly sing from hill to oceanside! Our hearts ever hold you, N. C. State, in the folds of our love and pride. Exercises of Graduation William Neal Reynolds Coliseum DR. JOHN TYLER CALDWELL, Chancellor Presiding May 17, 1975 PROCESSIONAL, 9:15 AM. Donald -

The Origins of Old Catholicism

The Origins of Old Catholicism By Jarek Kubacki and Łukasz Liniewicz On September 24th 1889, the Old Catholic bishops of the Netherlands, Switzerland and Germany signed a common declaration. This event is considered to be the beginning of the Union of Utrecht of the Old Catholic Churches, federation of several independent national Churches united on the basis of the faith of the undivided Church of the first ten centuries. They are Catholic in faith, order and worship but reject the Papal claims of infallibility and supremacy. The Archbishop of Utrecht a holds primacy of honor among the Old Catholic Churches not dissimilar to that accorded in the Anglican Communion to the Archbishop of Canterbury. Since the year 2000 this ministry belongs to Archbishop JorisVercammen. The following churches are members of the Union of Utrecht: the Old Catholic Church of the Netherlands, the Catholic Diocese of the Old Catholics in Germany, Christian Catholic Church of Switzerland, the Old Catholic Church of Austria, the Old Catholic Church of the Czech Republic, the Polish-Catholic Church and apart from them there are also not independent communities in Croatia, France, Sweden, Denmark and Italy. Besides the Anglican churches, also the Philippine Independent Church is in full communion with the Old Catholics. The establishment of the Old Catholic churches is usually being related to the aftermath of the First Vatican Council. The Old Catholic were those Catholics that refused to accept the doctrine of Papal Infallibility and the Universal Jurisdiction. One has to remember, however, that the origins of Old Catholicism lay much earlier. We shouldn’t forget, above all, that every church which really deserves to be called by that name has its roots in the church of the first centuries. -

The Puritan and Presbyterian Versions of the Netherlands Liturgy

THE PURITAN AND PRESBYTERIAN VERSIONS OF THE NETHERLANDS LITURGY DANIELJAMES MEETER Wainfleet,Ontario English Puritanism was defined in great part by its non-conformity to the Book of Common Prayer. But not all Puritans altogether rejected the discipline of written liturgies'. Some Puritans (and a few Scottish Presbyterians) had an established liturgy to contend with that was much more congenial to their Calvinism, the Netherlands Liturgy of the Dutch Reformed Church. These were the "Dutch Puritans," as the historian Keith Sprunger has labelled them, the exiles, expatriates, and merchants who set up English-speaking congregations in the Netherlands2. The Dutch Puritans of a conservative "presbyterian" bent were content to conform to the Netherlands Liturgy, publishing an English translation of it, the "Leyden Lyturgy," sometime around 16403. But others, to the consternation of the Dutch Reformed Church, refused the use of even this Calvinistic form of worship. In this article I will examine the varieties of Puritan contact with the Netherlands Liturgy during the early 1600's. I will begin by reviewing the Dutch Reformed Church's approach to liturgical conformity, as 1 See Horton Davies, TheWorship of theEnglish Puritans (Westminster: Dacre Press, 1948); see Bryan Spinks, Fromthe Lordand "The BestReformed Churches ":A Studyof theEucharistic Liturgyin the EnglishPuritan and SeparatistTraditions 1550-1633. Bibliotheca Ephemerides Liturgicae,"Subsidia," no. 33 (Rome: Centro LiturgicoVincenziano, Edizione Liturgiche, 1984);and see Bard Thompson, Liturgiesof theWestern Church, paperback reprint (NewYork: New American Library, 1974), pp. 310-41. 2 Keith Sprunger, DutchPuritanism: A Historyof Englishand Scottish Churches of theNetherlands in theSixteenth and SeventeenthCenturies, Studies in the History of Christian Thought, vol. -

十七世紀的諷刺文章: 閻和赫立(Jan and Gerrit)兩個荷蘭人教師的對話 Lampoon in the 17Th Century: Samen-Spraeck Tusschen Jan Ende Gerrit

《台灣學誌》第二期 2010 年 10 月 頁 131-142 十七世紀的諷刺文章: 閻和赫立(Jan and Gerrit)兩個荷蘭人教師的對話 Lampoon in the 17th Century: Samen-Spraeck tusschen Jan ende Gerrit 賀安娟 國立台灣師範大學台灣文化及語言文學研究所副教授 [email protected] Introduction 〈東印度群島巴達維亞城四個荷蘭人的閒談〉這篇諷刺文章是在 1663 年印刷的。 作品中包含四個人物,第一位是商人,第二位是軍官,第三位是船員,最後一位則是教 義問答教師。全文總共 24 頁,包括兩部分。Monumenta Taiwanica 期刊的第一期即以這 篇對話作品第一部分的翻譯為專輯。第二部分的標題為「前大員及福爾摩莎總督尼可拉. 福伯(Nicolaes Verburgh)任內的福爾摩莎政府」。此部分的附錄當中收錄另一篇文章, 題目為「閻及赫立(Jan and Gerrit)兩位荷蘭人學校教師的對話——曾經進駐台灣,分 別任職於蕭壠(今台南佳里)及法弗蘭(今雲林虎尾)」。現階段我們最感興趣的課題, 也是這兩位曾經在台灣居留數年的荷蘭人教師之間的對話。 正如標題所示,閻及赫立這兩位教師之間的談話提到他們的在台經驗。根據這篇故 事的敘事架構,閻來台灣的時間較早,而且被派遣到荷蘭人最早從事宣教活動的區域, 也就是蕭壠的南部。赫立則剛從東印度群島回到荷蘭。如此的情節安排可提供一個思考、 比較的視角,讓讀者來評比閻和赫立兩人的經歷。此外,他們的對話乃是以福伯總督從 1650 到 1653 年的執政為主題。閻在 1650 年代之前來台灣工作,而赫立至少在福伯執政 期間曾經住在台灣。因此讀者若依照敘事邏輯,針對兩人的觀點做比較,亦顯得相當合 理。閻和赫立偶然相遇,隨即展開對話,彼此交流他們在台灣擔任學校教師的經驗。整 個故事的鋪陳依循嘲諷文類的規範,他們兩人批判當時藉由東印度公司的名義所推行的 宗教活動如何剝削在地老百姓。照他們的觀察,在地原住民的困境乃是因教育政策的怪 異實施方式所造成的。赫立特別在意的,即是以當地語言所施行的宗教教育。他並不反 對在地人民以他們的母語來接受教育,而是抨擊這種方式帶給宣教師極大的困難,因為 宣教師需要較長的時間才能嫻熟當地語言中相當數量的詞彙。在此之前,學校教師還得 132 《台灣學誌》第二期 代理宣教師的工作,直到宣教師當中有人能夠以在地語言流暢宣講基督教教義。閻和赫 立兩人在談話中暗諷荷蘭人宣教師「忙著填飽荷包」。在此場景中,有一些嚴苛批評即 便是針對尤尼士牧師(Rev. Robert Junius),亦不令人意外。1643 年尤尼士牧師回到荷 蘭後便捲入一場宗教辯爭。根本的原因在於他同時向阿姆斯特丹的高等宣教法院,以及 十七主任官的最高議會,控訴台灣教會的狀況。在台宣教師接到這個消息之後,大員合 議會(the Tayouan Consistory)覺得迫不得已必須為自己的立場申辯,連當時自認委屈的 在台宣教師也對尤尼士加以反擊。於是,雙方在這場宣教論戰中一來一往,相互指控。 其間,1649 年 10 月尤尼士曾經於阿姆斯特丹的高等宣教法院出席為自己辯護,同時法 院的判決也對他有利,但整個論戰的戰火仍舊延燒到 1652 年才平息。大員合議會雖被要 求撤銷控訴,但事後多年論戰的後遺症依舊存在。尤其是在台灣的荷蘭人社區,尤尼士 這個名字被列為黑名單。在這樣的情境下,閻頗為驚訝,尤尼士回到荷蘭以後,居然還 能夠教導其他的荷蘭宣教師台灣的在地語言新港語,為未來派駐台灣來做行前訓練。 赫立曾經被派任到法弗蘭。他批評福伯總督任由宣教師予取予求,給他們太多執行 -

Island Beautiful

C H I NA APAN KOREA , J , AND FORMOSA Showi ng M issio n Statio ns o f Canadian C hurches Mission Statio ns Presbyteri an M ethodi st Angli can Provi nces Railways —i T he Great Wall Th e o le gle a l S e mlna w P r e s e n t e d b y Th e Re v . Ro b e r t H owa r d T H EI LAND A T I F L S B E U U I sland B ea utiful The S tory of Fifty Years i n North Formosa BY DUNCAN MACL EOD E A OF RE F TH BO RD FO IGN M ISSIONS O PRESBYTER I AN CHURCH I N CA NA DA C ONFED ERA T ON FE BU D NG T O RONT O I LI IL I . 1 923 CONTENTS CHA PTER I “ ILHA FORMOSA E EOPLET H I R R I E E E II TH P , RUL RS AND LIG ONS III THE PATHFINDER OF NORTH FORMOSA I V O E B E FI E M R A OUT TH PATH ND R . R V NEWEA . THE IN NORTH FORMOSA VI GROWTH OF THE NATIVE CHURCH VI I B K NEW I REA ING TRA LS VIII TO OTHER CITIES ALSO ’ I ! WOMEN S WORK ! WHAT OF THE FUTURE ? I U E FORMOSAN FACTS AND F G R S . I LLUSTRATI ONS PAGE TAMS UI HARB OR Fron ti spi ece THE FAMOUS FORMOSAN CLIFFS GOUGING CHI PS FROM A CAMPHOR TREE TEA PICKERS AT WORK TH E P FAMOUS TEM LE AT HOKKO CHURCH AT SI NTI AM E E E E E FI DE F G ORG L SLI MACKAY , TH PATH N R O NORTH F ORMO SA DR . -

Covery of the History of Taiwan 9 2

VU Research Portal Christian Contextualization in Formosa Lin, C.H. 2014 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Lin, C. H. (2014). Christian Contextualization in Formosa: A Remarkable Episode (1624-1662) of Reformed Mission History. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 09. Oct. 2021 Christian Contextualization in Formosa A Remarkable Episode (1624-1662) of Reformed Mission History Changhua Lin 1 2 VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT Christian Contextualization in Formosa A Remarkable Episode (1624-1662) of Reformed Mission History ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad Doctor aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. F.A. van der Duyn Schouten, in het openbaar te verdedigen ten overstaan van de promotiecommissie van de Faculteit der Godgeleerdheid op maandag 15 december 2014 om 11.45 uur in de aula van de universiteit, De Boelelaan 1105 door Chang-Hua Lin geboren te Hualien, Taiwan 3 promotor: prof. -

WILLIAM VAN DOODEWAARD, HUNTINGTON UNIVERSITY a Transplanted Church: the Netherlandic Roots and Development of the Free Reformed Churches of North America

WILLIAM VAN DOODEWAARD, HUNTINGTON UNIVERSITY A Transplanted Church: the Netherlandic Roots and Development of the Free Reformed Churches of North America Introduction and denominational development only came two hundred years later. These later arriv The history of Dutch Reformed denomina als reflected the intervening development of tions in North America dates back almost the church in the Netherlands, many now 400 years to the time when The Netherlands having a varied history of secession from was a maJor sea-power with colonial ambi the state church and ensuing union with tion. In 1609 the explorer Henry Hudson or separation from other secession groups. was sent out by the Dutch to examine pos Most of these immigrants settled into already sibilities for a colony in the New World. established Christian Reformed Church con Dutch colonization began soon afterwards gregations, some joined congregations of the with the formation of New Netherland Reformed Church in America, some chose under the banner of the Dutch West India existing Canadian Protestant denominations, Company. The colony at its peak consisted and the remainder established new denomi of what today makes up the states of New nations corresponding to other Dutch Re York, New Jersey, and parts of Delaware and formed denominations in the Netherlands.4 Connecticut.] With the colony came the establishment of the first Dutch Reformed One of the new presences in the late 1940s church in 1628 in the wilderness village of and early 1950s was a qUickly developing New Amsterdam. This small beginning of a association of independent Dutch Reformed viable Dutch community set in motion cen congregations sharing similar theological turies of Dutch migration to North America, convictions and seceder roots. -

Black Families in New Net Joyce D

Black Families in New Net Joyce D. oodf riend University of Denver N ew Netherland becamehome to a sizeablenumber of In the past decade,the conceptual basis for the study black people during its brief history. Personsof African of blacks in colonial America has altered dramatically. heritage were present in the Dutch West India Instead of focusing on the institution of slavery and its Company’s colony as early as 1626 and their numbers evolution over time, historians such as Michael Mullin, increased substantially over the years. Whether Peter Wood, Ira Berlin, Allan Kulikoff, T.H. Breen and transported from a Spanish, Portuguese,or Dutch pos- Stephen Innes, and Philip Morgan have turned their session or native born in the colony, the blacks of New attention to exploring the actions of black people them- Netherland invariably attracted the attention of their selves.3As Gary Nash succinctly put it in a recent review European co-residents. Referencesto black individuals essay, “Afro-American studies in the colonial period or to groups of blacks are scatteredthroughout the Dutch [were reoriented] from a white-centered to a black- recordsof government and church. Yet surprisingly little centered area of inquiry . [Scholars] stressed the is known about the lives of these Africans and Afro- creative role of blacks in shaping their lives and in Americans: their ethnic origins, languages, religion, developing a truly Afro-American culture.“4 Unless this rituals, music, family and kinship structures, work ex- revised perspective is introduced into investigations of periences,and communal life remain largely unexplored. blacks in New Netherland, we will be unable to offer any fresh insights into the lives of the peoples of African This assertionmay strike someof you as not only bold, descentwho resided in this colony. -

TICCIH XV Congress 2012

TICCIH Congress 2012 The International Conservation for the Industrial Heritage Series 2 Selected Papers of the XVth International Congress of the International Committee for the Conservation of the Industrial Heritage § SECTION II: PLANNING AND DESIGN 113 A Study of the Hydraulic Landscape in Taoyuan Tableland: the Past, Present and Future / CHEN, Chie-Peng 114 A Study on Preservation, Restoration and Reuse of the Industrial Heritage in Taiwan: The Case of Taichung Creative Cultural Park / YANG, Hong-Siang 138 A Study of Tianjin Binhai New Area’s Industrial Heritage / YAN, Mi 153 Selective Interpretation of Chinese Industrial Heritage Case study of Shenyang Tiexi District / FAN, Xiaojun 161 Economization or Heritagization of Industrial Remains? Coupling of Conservation and CONTENTS Urban Regeneration in Incheon, South Korea / CHO, Mihye 169 Preservation and Reuse of Industrial Heritage along the Banks of the Huangpu River in Shanghai / YU, Yi-Fan 180 Industrial Heritage and Urban Regeneration in Italy: the Formation of New Urban Landscapes / PREITE, Massimo 189 Rethinking the “Reuse” of Industrial Heritage in Shanghai with the Comparison of Industrial Heritage in Italy / TRISCIUOGLIO, Marco 200 § SECTION III: INTERPRETATION AND APPLICATION 207 The Japanese Colonial Empire and its Industrial Legacy / Stuart B. SMITH 208 FOREWORDS 1 “La Dificultad” Mine. A Site Museum and Interpretation Center in the Mining District of FOREWORD ∕ MARTIN, Patrick 2 Real del Monte and Pachuca / OVIEDO GAMEZ, Belem 219 FOREWORD ∕ LIN, Hsiao-Wei 3 Tracing