The Origins of Old Catholicism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Calvinism in the Context of the Afrikaner Nationalist Ideology

ASIAN AND AFRICAN STUDIES, 78, 2009, 2, 305-323 CALVINISM IN THE CONTEXT OF THE AFRIKANER NATIONALIST IDEOLOGY Jela D o bo šo vá Institute of Oriental Studies, Slovak Academy of Sciences, Klemensova 19, 813 64 Bratislava, Slovakia [email protected] Calvinism was a part of the mythic history of Afrikaners; however, it was only a specific interpretation of history that made it a part of the ideology of the Afrikaner nationalists. Calvinism came to South Africa with the first Dutch settlers. There is no historical evidence that indicates that the first settlers were deeply religious, but they were worshippers in the Nederlands Hervormde Kerk (Dutch Reformed Church), which was the only church permitted in the region until 1778. After almost 200 years, Afrikaner nationalism developed and connected itself with Calvinism. This happened due to the theoretical and ideological approach of S. J.du Toit and a man referred to as its ‘creator’, Paul Kruger. The ideology was highly influenced by historical developments in the Netherlands in the late 19th century and by the spread of neo-Calvinism and Christian nationalism there. It is no accident, then, that it was during the 19th century when the mythic history of South Africa itself developed and that Calvinism would play such a prominent role in it. It became the first religion of the Afrikaners, a distinguishing factor in the multicultural and multiethnic society that existed there at the time. It legitimised early thoughts of a segregationist policy and was misused for political intentions. Key words: Afrikaner, Afrikaner nationalism, Calvinism, neo-Calvinism, Christian nationalism, segregation, apartheid, South Africa, Great Trek, mythic history, Nazi regime, racial theories Calvinism came to South Africa in 1652, but there is no historical evidence that the settlers who came there at that time were Calvinists. -

Missionary History of the Dutch Reformed Church

Page 1 of 2 Book Review Missionary history of the Dutch Reformed Church Being missionary, being human is a must, especially for those with an interest in missiology. It not Book Title: Being missionary, being only provides a fresh perspective on the missionary history of the Dutch Reformed Church (DRC) human in South Africa, it also provides a clear description of the interactive relationship between context and mission. The author is a respected missiologist who is also well acquainted with the history of Book Cover: mission in the Southern African context. His method of research can be termed an interdisciplinary approach of interaction between culture, religion, and political economy. He describes the social history in terms of waves of change. His intention is to describe the periods he distinguishes as waves, because this specific term makes good sense when describing the periods of extraordinary mission endeavor. The first wave describes the period, 1779−1834. In what he calls ’a reflection on the early Dutch Reformed Mission’, he describes the period that falls in the framework of the freeing of the slaves, Author: as well as the development of a colonial society in the Cape Colony. This is also the period of Willem A. Saayman mission-awakening in the protestant churches of Europe. It was during this time that Van Lier and Vos had established a ministry with far-reaching consequences in the Cape Colony. Both these ISBN: ministers cultivated a much greater sense of mission involvement amongst the free-burghers in the 9781875053650 Colony. During this period the focus of mission work was mostly directed towards the slaves – a Publisher: group that was not only subjected to the worst possible human brutalities and dehumanisation, but Cluster, Pietermaritzburg, was also regarded as non-Christian. -

HISTORICAL ANTECEDENTS of ST. PIUS X's DECREE on FREQUENT COMMUNION JOHN A

HISTORICAL ANTECEDENTS OF ST. PIUS X's DECREE ON FREQUENT COMMUNION JOHN A. HARDON, SJ. West Baden College HPHE highest tribute to the apostolic genius of St. Pius X was paid by * his successor on the day he raised him to the honors of the altar: "in the profound vision which he had of the Church as a society, Pius X recognized that it was the Blessed Sacrament which had the power to nourish its intimate life substantially, and to elevate it high above all other human societies." To this end "he overcame the prejudices springing from an erroneous practice and resolutely promoted frequent, even daily, Communion among the faithful," thereby leading "the spouse of Christ into a new era of Euchari^tic life."1 In order to appreciate the benefits which Pius X conferred on the Church by his decree on frequent Communion, we might profitably examine the past half-century to see how the practice which he advo cated has revitalized the spiritual life of millions of the faithful. Another way is to go back in history over the centuries preceding St. Pius and show that the discipline which he promulgated in 1905 is at once a vindication of the Church's fidelity to her ancient traditions and a proof of her vitality to be rid of whatever threatens to destroy her divine mission as the sanctifier of souls. The present study will follow the latter method, with an effort to cover all the principal factors in this Eucharistic development which had its roots in the apostolic age but was not destined to bear full fruit until the present time. -

The Puritan and Presbyterian Versions of the Netherlands Liturgy

THE PURITAN AND PRESBYTERIAN VERSIONS OF THE NETHERLANDS LITURGY DANIELJAMES MEETER Wainfleet,Ontario English Puritanism was defined in great part by its non-conformity to the Book of Common Prayer. But not all Puritans altogether rejected the discipline of written liturgies'. Some Puritans (and a few Scottish Presbyterians) had an established liturgy to contend with that was much more congenial to their Calvinism, the Netherlands Liturgy of the Dutch Reformed Church. These were the "Dutch Puritans," as the historian Keith Sprunger has labelled them, the exiles, expatriates, and merchants who set up English-speaking congregations in the Netherlands2. The Dutch Puritans of a conservative "presbyterian" bent were content to conform to the Netherlands Liturgy, publishing an English translation of it, the "Leyden Lyturgy," sometime around 16403. But others, to the consternation of the Dutch Reformed Church, refused the use of even this Calvinistic form of worship. In this article I will examine the varieties of Puritan contact with the Netherlands Liturgy during the early 1600's. I will begin by reviewing the Dutch Reformed Church's approach to liturgical conformity, as 1 See Horton Davies, TheWorship of theEnglish Puritans (Westminster: Dacre Press, 1948); see Bryan Spinks, Fromthe Lordand "The BestReformed Churches ":A Studyof theEucharistic Liturgyin the EnglishPuritan and SeparatistTraditions 1550-1633. Bibliotheca Ephemerides Liturgicae,"Subsidia," no. 33 (Rome: Centro LiturgicoVincenziano, Edizione Liturgiche, 1984);and see Bard Thompson, Liturgiesof theWestern Church, paperback reprint (NewYork: New American Library, 1974), pp. 310-41. 2 Keith Sprunger, DutchPuritanism: A Historyof Englishand Scottish Churches of theNetherlands in theSixteenth and SeventeenthCenturies, Studies in the History of Christian Thought, vol. -

St. Francis of Assisi Parish ! ! !! ! the Catholic Community in Weston ! Sunday, Aug

35 NǐǓLJNJdžǍDž RǐǂDž ! WdžǔǕǐǏ, CǐǏǏdžDŽǕNJDŽǖǕ 06883 ! ST. FRANCIS! We extend a warm welcome to all who ! worship at our church! We hope that you ! will find our parish community to be a place ! where your faith is nourished. ! OF ASSISI ! ! Rectory: 203 !227 !1341 FAX: 203 !226 !1154 Website: www.stfrancisweston.org Facebook: Saint Francis of Assisi ! The PARISH! Catholic Community in Weston Religious Education/Youth Ministry: ! ! 203 !227 !8353 THE CATHOLIC COMMUNITY IN WESTON Preschool: 203 !454 !8646 ! ! RdžDŽǕǐǓǚ OLJLJNJDŽdž HǐǖǓǔ ! August 4, 2019 Monday Through Friday 9:00 a.m. ! 4:00 p.m. ! SǖǏDžǂǚ Mǂǔǔdžǔ ! Saturday Vigil ! 5:00 P.M. Sundays 8:00, 9:30 ! Family Mass, 11:00 A.M. 5:00 p.m. Scheduled Weekly ! Except for Christmas & Easter. ! WdždžnjDžǂǚ Mǂǔǔdžǔ ! Monday ! Friday ! 7:30 A.M. Saturday & Holidays ! 9:00 A.M. ! HǐǍǚ Dǂǚ Mǂǔǔdžǔ ! 7:30 A.M. , Noon , 7:00 P.M. ! NǐǗdžǏǂ ! Novena prayers in honor of Our Lady of the Miraculous Medal every Saturday following the 9:00 A.M. Mass. ! SǂDŽǓǂǎdžǏǕ OLJ RdžDŽǐǏDŽNJǍNJǂǕNJǐǏ ! Saturdays, 4:00 !4:45 P.M.; Sundays 4:00 P.M. ! SǂDŽǓǂǎdžǏǕ OLJ BǂǑǕNJǔǎ ! The Sacrament of Baptism is offered every Sunday at 12:00 noon. Please make arrangements for the Pre !Baptismal instructions after the birth of the child in person at the rectory. Pre !instruction for both parents is required. ! SǂDŽǓǂǎdžǏǕ OLJ MǂǕǓNJǎǐǏǚ ! Arrangements must be made at the rectory in person by the couple. Where possible, arrangements should be made one year in advance and no later than six months. ! SǂDŽǓǂǎdžǏǕ OLJ AǏǐNJǏǕNJǏLj ! Communal anointings of the sick are celebrated. -

Irenaeus Shed Considerable Light on the Place of Pentecostal Thought for Histories That Seek to Be International and Ecumenical

Orphans or Widows? Seeing Through A Glass Darkly By Dr. Harold D. Hunter Abstract Scholars seeking to map the antecedents of Pentecostal distinctives in early Christendom turn to standard reference works expecting to find objective summaries of the writings of Church Fathers and Mothers. Apparently dismissing the diversity of the biblical canon itself, the writers of these reference works can be found manipulating patristic texts in ways which reinforce the notion that the Classical Pentecostal Movement is a historical aberration. This prejudice is evident in the selection of texts and how they are translated and indexed as well as the surgical removal of pertinent sections of the original texts. This problem can be set right only by extensive reading of the original sources in the original languages. The writings of Irenaeus shed considerable light on the place of Pentecostal thought for histories that seek to be international and ecumenical. Introduction I began advanced study of classical Pentecostal distinctives at Fuller Theological Seminary in the early 1970s. Among those offering good advice was the then academic dean of Vanguard University in nearby Costa Mesa, California, Russell P. Spittler. While working on a patristic project, Spittler emphasized the need for me to engage J. Quasten and like scholars. More recently I utilized Quasten et al in dialogue with William Henn in a paper presented to the International Roman Catholic - Pentecostal Dialogue which convened July 23-29, 1999 in Venice, Italy. What follows is the substance of the paper delivered at that meeting.i The most influential editions of Church Fathers and Mothers available in the 20th Century suffered from inadequate translation of key passages. -

Blaise Pascal: from Birth to Rebirth to Apologist

Blaise Pascal: From Birth to Rebirth to Apologist A Thesis Presented To Dr. Stephen Strehle Liberty University Graduate School In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Course THEO 690 Thesis by Lew A. Weider May 9, 1990 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4 Chapter I. JANSENISM AND ITS INFLUENCE ON BLAISE PASCAL 12 The Origin of Jansenism . 12 Jansenism and Its Influence on the Pascals . 14 Blaise Pascal and his Experiments with Science and Technology . 16 The Pascal's Move Back to Paris . 19 The Pain of Loneliness for Blaise Pascal . 21 The Worldly Period . 23 Blaise Pascal's Second Conversion 26 Pascal and the Provincial Lettres . 28 The Origin of the Pensees . 32 II. PASCAL AND HIS MEANS OF BELIEF 35 The Influence on Pascal's Means of Belief 36 Pascal and His View of Reason . 42 Pascal and His View of Faith . 45 III. THE PENSEES: PASCAL'S APOLOGETIC FOR THE CHRISTIAN FAITH 50 The Wager Argument . 51 The Miracles of Holy Scripture 56 The Prophecies . 60 CONCLUSION . 63 BIBLIOGRAPHY . 65 INTRODUCTION Blaise Pascal was a genius. He was revered as a great mathematician and physicist, an inventor, and the greatest prose stylist in the French language. He was a defender of religious freedom and an apologist of the Christian faith. He was born June 19, 1623, at Clermont, the capital of Auvergne, which was a small town of about nine thousand inhabitants. He was born to Etienne and Antoinette Pascal. Blaise had two sisters, Gilberte, born in 1620, and Jacqueline, born in 1625. Blaise was born into a very influential family. -

Church and State in Dutch Formosa

Church and State in Dutch Formosa Joel S. Fetzer J. Chrisopher Soper Social Science Division Pepperdine University Malibu, CA 90263-4372 [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT: This paper examines the politics of church-state interactions in Dutch Formosa. How did Dutch Christians and local indigenous converts relate to the colonial government in Taiwan during the Dutch era (1624–1662)? Did Protestant missionaries and their followers play a mainly priestly or prophetic role when dealing with the Dutch East India Company and its representatives in Taiwan? Did Dutch authorities adopt a laissez-faire attitude to native and foreign Christians' religious practices, or did they actively support the missionary effort in Formosa? This essay tests Anthony Gill’s political-economic model of church-state interaction by analyzing published collections of primary Dutch-language and translated documents on this topic and by examining related secondary works. The study concludes that although a few missionaries tried to soften the edges of colonial dominance of Taiwanese aborigines, most clerics enthusiastically participated in the Netherlands' brutal suppression of indigenous culture and even some aboriginal groups. The government, meanwhile, appears to have endorsed missionary activities on the assumption that conversion would "civilize the natives," who would in turn embrace Dutch colonization. In its relatively brief period of colonial control over Formosa (1624-1662), the Dutch state established a remarkably vigorous administrative apparatus that attempted to gain profit from the island’s abundant natural resources and to convert and Christianize the natives. Under the auspices of the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC), or Dutch East India Company, a highly complex administrative structure developed that included Calvinist missionaries and political leaders on the island, colonial authorities in the company’s Asian headquarters in Batavia, and a board of directors in the Netherlands. -

Confirmation Workbook 2016-2017

The Holy Sacrament of Confirmation Workbook 2016-2017 Icon of Pentecost © by Monastery Icons – www.monasteryicons.com Used with permission. “Come Holy Spirit and inflame our hearts with the fire of divine love!” Darryl Adams 540-622-8073, [email protected] St. John the Baptist Roman Catholic Church, Front Royal, VA A.M.D.G Table of Contents Weekly Class Schedule 5 Confirmation Preparation Entrance Questionnaire 6 Note to Parents 7 Specific Confirmation Prayers 8 Summary of the Faith of the Church 9 Summary of Basic Prayers 10 Preparation Checklist 12 Forms and Requirements (Final Requirements start on page 121) Confirmation Sponsor Certificate*1 14 Choosing a Patron Saint and Sponsor 16 Sponsor & Proxy Form* 19 Retreat from* 21 Patron Saint Report 23 Historical Report 24 Gospel Report 26 Apostolic Project 28 Apostolic Project Proposal Form 31 Apostolic Project Summary Form (2 pages) 33 THE EXISTENCE OF GOD 36 The Problem of Evil 39 Hell is Real 43 Guardian Angels including information from St. Padre Pio 47 Guardian Angel Litany 51 The Last Things 52 SACRED SCRIPTURE 55 Are the Books of the New Testament Reliable Historical Documents? 56 How do the Books of the New Testament indicate the manner in which they are supposed to be read? 57 Where the rubber hits the road… 59 How does the Church further instruct us on how to read the Holy Bible? 60 The Bottom Line 61 Diagram of Highlights of Christ’s Life 62 THE DIVINITY OF CHRIST AND THE HOLY TRINITY 63 What Jesus did and said can be done by no man 64 Who do people say that He is? 66 -

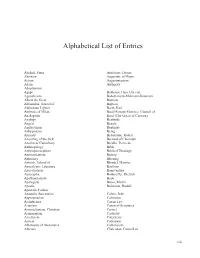

A-Z Entries List

Alphabetical List of Entries Abelard, Peter Attributes, Divine Abortion Augustine of Hippo Action Augustinianism Adam Authority Adoptionism Agape Balthasar, Hans Urs von Agnosticism Bañezianism-Molinism-Baianism Albert the Great Baptism Alexandria, School of Baptists Alphonsus Liguori Barth, Karl Ambrose of Milan Basel-Ferrara-Florence, Council of Anabaptists Basil (The Great) of Caesarea Analogy Beatitude Angels Beauty Anglicanism Beguines Anhypostasy Being Animals Bellarmine, Robert Anointing of the Sick Bernard of Clairvaux Anselm of Canterbury Bérulle, Pierre de Anthropology Bible Anthropomorphism Biblical Theology Antinomianism Bishop Antinomy Blessing Antioch, School of Blondel, Maurice Apocalyptic Literature Boethius Apocatastasis Bonaventure Apocrypha Bonhoeffer, Dietrich Apollinarianism Book Apologists Bucer, Martin Apostle Bultmann, Rudolf Apostolic Fathers Apostolic Succession Calvin, John Appropriation Calvinism Architecture Canon Law Arianism Canon of Scriptures Aristotelianism, Christian Carmel Arminianism Casuistry Asceticism Catechesis Aseitas Catharism Athanasius of Alexandria Catholicism Atheism Chalcedon, Council of xiii Alphabetical List of Entries Character Diphysitism Charisma Docetism Chartres, School of Doctor of the Church Childhood, Spiritual Dogma Choice Dogmatic Theology Christ/Christology Donatism Christ’s Consciousness Duns Scotus, John Chrysostom, John Church Ecclesiastical Discipline Church and State Ecclesiology Circumincession Ecology City Ecumenism Cleric Edwards, Jonathan Collegiality Enlightenment -

WILLIAM VAN DOODEWAARD, HUNTINGTON UNIVERSITY a Transplanted Church: the Netherlandic Roots and Development of the Free Reformed Churches of North America

WILLIAM VAN DOODEWAARD, HUNTINGTON UNIVERSITY A Transplanted Church: the Netherlandic Roots and Development of the Free Reformed Churches of North America Introduction and denominational development only came two hundred years later. These later arriv The history of Dutch Reformed denomina als reflected the intervening development of tions in North America dates back almost the church in the Netherlands, many now 400 years to the time when The Netherlands having a varied history of secession from was a maJor sea-power with colonial ambi the state church and ensuing union with tion. In 1609 the explorer Henry Hudson or separation from other secession groups. was sent out by the Dutch to examine pos Most of these immigrants settled into already sibilities for a colony in the New World. established Christian Reformed Church con Dutch colonization began soon afterwards gregations, some joined congregations of the with the formation of New Netherland Reformed Church in America, some chose under the banner of the Dutch West India existing Canadian Protestant denominations, Company. The colony at its peak consisted and the remainder established new denomi of what today makes up the states of New nations corresponding to other Dutch Re York, New Jersey, and parts of Delaware and formed denominations in the Netherlands.4 Connecticut.] With the colony came the establishment of the first Dutch Reformed One of the new presences in the late 1940s church in 1628 in the wilderness village of and early 1950s was a qUickly developing New Amsterdam. This small beginning of a association of independent Dutch Reformed viable Dutch community set in motion cen congregations sharing similar theological turies of Dutch migration to North America, convictions and seceder roots. -

Black Families in New Net Joyce D

Black Families in New Net Joyce D. oodf riend University of Denver N ew Netherland becamehome to a sizeablenumber of In the past decade,the conceptual basis for the study black people during its brief history. Personsof African of blacks in colonial America has altered dramatically. heritage were present in the Dutch West India Instead of focusing on the institution of slavery and its Company’s colony as early as 1626 and their numbers evolution over time, historians such as Michael Mullin, increased substantially over the years. Whether Peter Wood, Ira Berlin, Allan Kulikoff, T.H. Breen and transported from a Spanish, Portuguese,or Dutch pos- Stephen Innes, and Philip Morgan have turned their session or native born in the colony, the blacks of New attention to exploring the actions of black people them- Netherland invariably attracted the attention of their selves.3As Gary Nash succinctly put it in a recent review European co-residents. Referencesto black individuals essay, “Afro-American studies in the colonial period or to groups of blacks are scatteredthroughout the Dutch [were reoriented] from a white-centered to a black- recordsof government and church. Yet surprisingly little centered area of inquiry . [Scholars] stressed the is known about the lives of these Africans and Afro- creative role of blacks in shaping their lives and in Americans: their ethnic origins, languages, religion, developing a truly Afro-American culture.“4 Unless this rituals, music, family and kinship structures, work ex- revised perspective is introduced into investigations of periences,and communal life remain largely unexplored. blacks in New Netherland, we will be unable to offer any fresh insights into the lives of the peoples of African This assertionmay strike someof you as not only bold, descentwho resided in this colony.