Station Area Planning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cruise Handling.Cdr

Cruise Handling MUMBAI GOA OPERATIONAL HEADQUARTERS White House, Church Road, Manickpur, Vasai (W) MUMBAI 401 202. Mahatashtra INDIA. Tel.:- +91 22 65720888. Mobile: +91 9168259988 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.tvsholidaymakers.com Cruise Handling India Namaste !!! International cruise companies are increasingly looking to the east, finding new destinations and ports of call for their cruise programs. As the demand for cruise vacations grows and passenger capacities expand, more and more cruise lines are finding India an increasingly popular destination. The Indian coastline is massive, the ports of call many, each with its own flavor and history. Amongst them are Mumbai, Tarkali, Goa, Cochi, Cananore, Chennai, Lakshadweep and Andaman Islands, smaller ports of Gujarat and more. Our Specialists Years of experience in handling cruise ships calling at Indian ports at MUMBAI / GOA / TARKALI (new port in Maharashtra Konkan) give our team the competitive edge to ensure that your passengers are extended professional, personalized services. Our specialists in ground operations ensure perfect execution of all arrangements, seamlessly. Services we offer.... Ground Transportation - AC Coaches & AC Cars [Small / Medium/ Executive] for Cruise guest Sightseeing & Elephanta caves excursion, Shore excursions, Day outing etc. Planning the itinerary with Principal Agents and inputs on port details and services. Port inspection and operational feasibility. Innovative shore excursions with the best of local guides govt. approved. Liaison with Govt. Authorities, Shipping Agents and Local agents. Complete turn around operations in our region - International / Domestic Airport. TVS Holiday Makers offers one of the largest, newest and most comfortable air-conditioned fleets in India- Mumbai, Tarkali, Goa. We can easily accommodate any size group as we feature 45, 39, 22, 15, 10 passenger coaches as well as 4X4 Fortuners and Private car for VIP’S. -

00 Stage 1 Final Report

Action Plan for Heritage Conservation and Environment Improvement of Erangal Precinct INCEPTION REPORT May 2010 Submitted to Mumbai Metropolitan Region – Heritage Conservation Society (MMR-HCS) MMRDA, Bandra Kurla Complex, Bandra (East), Mumbai 400 051 Prepared by HCP Design and Project Management Pvt. Ltd. Paritosh, Usmanpura, Ahmedabad- 380 013 Action Plan for Erangal Precinct PROJECT TEAM Project Director Shirley Ballaney, Architect – Urban and Regional Planner Project Leader Bindu Nair, Geographer – Urban and Regional Planner The Team Sonal Shah, Architect – Urban Planner Archana Kothari, Architect – Urban Planner Krupa Bhardwaj, Architect – Urban Planner Rashmita Jadav, Architect Atul Patel, CAD Specialist Suresh Patel, CAD Technician Action Plan for Erangal Precinct CONTENTS 1 Background to the Project 1.1 Significance of the Project 1.2 Objectives of the Project 1.3 Scope of Work (TOR) 1.4 Outputs and Schedule 2 Detailed SOW and Road Map 2.1 Detailed SOW and Methodology 2.2 Work Plan 2.3 Changed Focus of the Project 3 Base Map 4 Introduction 4.1 Location and Connectivity 4.2 Regional Context 4.3 History and Growth of Erangal 5 Preliminary Assessments 5.1 Development Plan Proposals 5.2 Built Fabric and Settlement Structure/Pattern 5.3 Access and Road Networks 5.4 Land Use 5.5 Intensity of development/FSI utilization 5.6 Land Ownership Pattern 5.7 Landmarks and public spaces 5.8 Community Pattern 5.9 Occupational Pattern 5.10 Typology of Structures 5.11 Cultural Practices 5.12 Sewerage 5.13 Solid Waste Management 5.14 Social Amenities 6 Review of the Precinct Boundary 6.1 Rational for Revising the Precinct Boundary 6.2 Details of the Revised Precinct Boundary and the Buffer Zone Appendices Appendix 1: Review of some of the Material Appendix 2: Questionnaire Action Plan for Erangal Precinct LIST OF MAPS Map No. -

Mumbai Railway Vikas Corporation Limited Detailed Project Report for Proposed 3 & 4 Railway Lines Between Pune – Lonavala

Detailed Project Report – 3rd & 4th Lines between Pune-Lonavala section (63. 84 Km) of Central Railway MUMBAI RAILWAY VIKAS CORPORATION LIMITED DETAILED PROJECT REPORT FOR PROPOSED 3RD & 4TH RAILWAY LINES BETWEEN PUNE – LONAVALA JUNE 2016 Mumbai Railway Vikas Corporation Ltd. Page 1 Detailed Project Report – 3rd & 4th Lines between Pune-Lonavala section (63. 84 Km) of Central Railway 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Brief History: rd th PECT Survey for 3 & 4 Line between Pune-Lonavala was sanctioned in 1997 – 98 and report was submitted to Railway Board in 2001 at a total cost of Rs.322.44 cr. Further, RECT survey for only 3rd line was sanctioned by Railway Board in 2011-12 and the Survey Report was under scrutiny at HQ. The work for Third B. G. Line between Pune -Lonavala was sanctioned by Railway Board vide Pink Book Item no. 22 of Demand No. 16 under Doubling for the year 2015-16 at the cost of Rs. 800 crores. Detailed Project Report with feasibility study and detailed construction estimate for proposed third B.G. line was prepared by Central Railway at a total cost of Rs. 943.60 Crore. It was sanctioned by Railway Board vide letter No. 2015/W1/NER/DL/BSB-MBS-ALD dated 31.03.2016 under Gross Budgetary support. The work has been assigned to Mumbai Railway Vikas Corporation Ltd (MRVC) vide Railway Board‟s letter No. 2015/W-1/Genl/Presentation/Pt dated 11.12.205. Hon‟ble Chief Minister of Government of Maharashtra vide his D.O. letter No. MRD-3315/CR44/UD-7 dated 23.02.2016 addressed to Hon‟ble Minister of Railways had requested for sanction of 3rd and 4th line between Pune – Lonavala to run suburban and main line train services. -

By Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Vidyavachaspati (Doctor of Philosophy) Faculty for Moral and Social Sciences Department Of

“A STUDY OF AN ECOLOGICAL PATHOLOGICAL AND BIO-CHEMICAL IMPACT OF URBANISATION AND INDUSTRIALISATION ON WATER POLLUTION OF BHIMA RIVER AND ITS TRIBUTARIES PUNE DISTRICTS, MAHARASHTRA, INDIA” BY Dr. PRATAPRAO RAMGHANDRA DIGHAVKAR, I. P. S. THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF VIDYAVACHASPATI (DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY) FACULTY FOR MORAL AND SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY TILAK MAHARASHTRA VIDHYAPEETH PUNE JUNE 2016 CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the entire work embodied in this thesis entitled A STUDY OFECOLOGICAL PATHOLOGICAL AND BIOCHEMICAL IMPACT OF URBANISATION AND INDUSTRILISATION ON WATER POLLUTION OF BHIMA RIVER AND Its TRIBUTARIES .PUNE DISTRICT FOR A PERIOD 2013-2015 has been carried out by the candidate DR.PRATAPRAO RAMCHANDRA DIGHAVKAR. I. P. S. under my supervision/guidance in Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune. Such materials as has been obtained by other sources and has been duly acknowledged in the thesis have not been submitted to any degree or diploma of any University or Institution previously. Date: / / 2016 Place: Pune. Dr.Prataprao Ramchatra Dighavkar, I.P.S. DECLARATION I hereby declare that this dissertation entitled A STUDY OF AN ECOLOGICAL PATHOLOGICAL AND BIO-CHEMICAL IMPACT OF URBANISNTION AND INDUSTRIALISATION ON WATER POLLUTION OF BHIMA RIVER AND Its TRIBUTARIES ,PUNE DISTRICT FOR A PERIOD 2013—2015 is written and submitted by me at the Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The present research work is of original nature and the conclusions are base on the data collected by me. To the best of my knowledge this piece of work has not been submitted for the award of any degree or diploma in any University or Institution. -

MMR-Heritage Conservation Society

MMR - H E R I T A G E CONSERVATION SOCIETY ANNUAL REPORT 2015 - 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Contents Page No 1 Board of Governors………………………….. 03 2 Introduction…………………………………….. 05 3 Objectives of the Society………………….. 05 4 Activities during the year 2015-16 4.1 New project Proposals……………………… 08 4.2 On-going Projects…………………………….. 11 4.3 Concluded Projects…………………………… 14 5 Training and Awareness Programme.. 16 6 Publications……………………………………… 18 7 Funds………………………………………………… 19 1 2 1. BOARD OF GOVERNORS OF THE SOCIETY A. EX-OFFICIO GOVERNORS 1. Shri. U.P.S. Madan President Metropolitan Commissioner, MMRDA. 2. The representative of the Municipal Governor Commissioner, Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai 3. The representative of the Managing Director, Governor CIDCO 4. Shri. Sanjay K. Patil Governor Director, Archaeology & Museums,, Maharashtra State 5. Dr. Ramanath Jha Governor Chairman, Mumbai Heritage Conservation Committee 6. Shri. Sabyasachi Mukherjee Governor Director General, Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya B. NOMINEES OF ORGANISATIONS /ASSOCIATIONS 7. Prof. Mustansir Dalvi Governor Si Sir J.J College of Architecture 8. Shri. Madan Singh Chouhan Governor Superintending Archaeologist, Archaeological Survey of India, Mumbai C. INDIVIDUAL EXPERTS 9. Shri. D.T. Joseph, IAS (Retd.),Ex-Principal Governor Secretary, UDD, Govt. of Maharashtra 10. Shri. S. P. Pendharkar Governor Urban Planner 3 11. Shri. David Cardoz Governor Conservation Architect 12. Ms. Alpa Sheth Governor Structural Engineer 13. Shri. A.P. Jamkhedkar Governor Historian D. PRINCIPAL OFFICERS OF THE SOCIETY 1. Ms. Uma Adusumilli, Director Chief, Planning Division, MMRDA. 2. (a) Shri. Sunil Pimpalkhute Treasurer (Upto:23/07/2015) (b) Shri P.G. Mohite (From:24/07/2015) Financial Advisor, MMRDA 3. -

Heritage List

LISTING GRADING OF HERITAGE BUILDINGS PRECINCTS IN MUMBAI Task II: Review of Sr. No. 317-632 of Heritage Regulation Sr. No. Name of Monuments, Value State of Buildings, Precincts Classification Preservation Typology Location Ownership Usage Special Features Date Existing Grade Proposed Grade Photograph 317Zaoba House Building Jagananth Private Residential Not applicable as the Not applicable as Not applicable as Not applicable as Deleted Deleted Shankersheth Marg, original building has been the original the original the original Kalbadevi demoilshed and is being building has been building has been building has been rebuilt. demoilshed and is demoilshed and is demoilshed and is being rebuilt. being rebuilt. being rebuilt. 318Zaoba Ram Mandir Building Jagananth Trust Religious Vernacular temple 1910 A(arc), B(des), Good III III Shankersheth Marg, architecture.Part of building A(cul), C(seh) Kalbadevi in stone.Balconies and staircases at the upper level in timber. Decorative features & Stucco carvings 319 Zaoba Wadi Precinct Precinct Along Jagannath Private Mixed Most features already Late 19th century Not applicable as Poor Deleted Deleted Shankershet Marg , (Residential & altered, except buildings and early 20th the precinct has Kalbadevi Commercial) along J. S. Marg century lost its architectural and urban merit 320 Nagindas Mansion Building At the intersection Private (Nagindas Mixed Indo Edwardian hybrid style 19th Century A(arc), B(des), Fair II A III of Dadasaheb Purushottam Patel) (Residential & with vernacular features like B(per), E, G(grp) Bhadkamkar Marg Commercial) balconies combined with & Jagannath Art Deco design elements Shankersheth & Neo Classical stucco Road, Girgaum work 321Jama Masjid Building Janjikar Street, Trust Religious Built on a natural water 1802 A(arc), A(cul), Good II A II A Near Sheikh Menon (Jama Masjid of (Muslim) source, displays Islamic B(per), B(des),E, Street Bombay Trust) architectural style. -

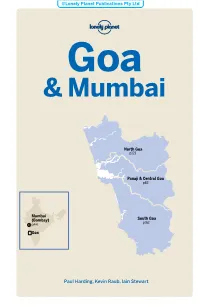

Goa & Mumbai 8

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Goa & Mumbai North Goa p121 Panaji & Central Goa p82 Mumbai South Goa (Bombay) p162 p44 Goa Paul Harding, Kevin Raub, Iain Stewart PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to MUMBAI PANAJI & Goa & Mumbai . 4 (BOMBAY) . 44 CENTRAL GOA . 82 Goa & Mumbai Map . 6 Sights . 47 Panaji . 84 Goa & Mumbai’s Top 14 . .. 8 Activities . 55 Around Panaji . 96 Need to Know . 16 Courses . 55 Dona Paula . 96 First Time Goa . 18 Tours . 55 Chorao Island . 98 What’s New . 20 Sleeping . 56 Divar Island . 98 If You Like . 21 Eating . 62 Old Goa . 99 Month by Month . 23 Drinking & Nightlife . 69 Goa Velha . 106 Itineraries . 27 Entertainment . 72 Ponda Region . 107 Beach Planner . 31 Shopping . 73 Molem Region . .. 111 Activities . 34 Information . 76 Beyond Goa . 114 Travel with Children . 39 Getting There & Away . 78 Hampi . 114 Getting Around . 80 Anegundi . 120 Regions at a Glance . .. 41 TUKARAM.KARVE/SHUTTERSTOCK © TUKARAM.KARVE/SHUTTERSTOCK © GOALS/SHUTTERSTOCK TOWERING ATTENDING THE KALA GHODA ARTS FESTIVAL P47, MUMBAI PIKOSO.KZ/SHUTTERSTOCK © PIKOSO.KZ/SHUTTERSTOCK STALL, ANJUNA FLEA MARKET P140 Contents UNDERSTAND NORTH GOA . 121 Mandrem . 155 Goa Today . 198 Along the Mandovi . 123 Arambol (Harmal) . 157 History . 200 Reis Magos & Inland Bardez & The Goan Way of Life . 206 Nerul Beach . 123 Bicholim . .. 160 Delicious India . 210 Candolim & Markets & Shopping . 213 Fort Aguada . 123 SOUTH GOA . 162 Arts & Architecture . 215 Calangute & Baga . 129 Margao . 163 Anjuna . 136 Around Margao . 168 Wildlife & the Environment . .. 218 Assagao . 142 Chandor . 170 Mapusa . 144 Loutolim . 170 Vagator & Chapora . 145 Colva . .. 171 Siolim . 151 North of Colva . -

The Editorial

MOVING BEYOND PAPERS THE EDITORIAL Hello there, folks! First of all, we would like to wish you a very New Year,has penned down all the things 'Fated to the Sword' series, with even more Happy New Year on behalf of our entire team that are new and trending among the young exciting twists and turns. This time around, of The Ruiaite Monthly! Just as the New Year and the elderly. Taking the New Year theme Safarnama has decided to help us explore brings with it an aura of joy, hope, love and ahead, Behind The Scenes talks about what our very own backyard called “Mumbai”, but positivity, we would like to present you our resolutions our Ruiaites are planning to from a true traveller's eyes. Reporting brings very first edition of the year 2018 with the break ( oops.. .we meant to say “make”! ). to us the hip and happening updates on UA'17 same level of love and positivity. Along the same lines, Insight brings to us a and other events. In Student's Corner, you Let’s check what every column has in store very interesting theme called 'New Year, shall see yet another magnificent piece of for you all this time. To begin New Me', but with a small twist. Open Forum poetry by our amateur. After all the reading with,BuzzAround gives us a reality check by fascinates us with tales of Dystopian business, go check our Artwall for a visual talking about the Bhima- Koregaon issue that societies. Tech Tricked follows the YouTube treat connected to the city! recently crippled Mumbai and Pune for two trend and brings to us the 'Science Rewind of Now then, Ruiaites, go ahead, begin your entire days, whileCareerWise brings to us 2017 ' whereas Science of Everything chalks new year with a bang! How to do that, you the “wise career options” in the Indian Film out the hits and misses of 2017. -

Mumbai on the Move Approximately 4¼ Hours $$ Enjoyed

A Day in the Life: Mumbai on the Move Approximately 4¼ Hours $$ Enjoyed it? 4 out of 5 Value 3 out of 5 1 out of 1(100%)reviewers would recommend this product to a friend. Read 1 review | Write a review Experience the real, everyday Mumbai, including the highlights of this fascinating city, with its Western monuments and Eastern sensibilities. Begin at the beginning, with the Gateway of India. This is the city’s most famous landmark—an Indo-Saracenic archway built in 1911 to commemorate the visit of King George V and Queen Mary. It was originally conceived as an entry point for passengers arriving on P&O steamers from England; today, it is remembered more often as the place from which the British staged their final departure. You will stop here for photographs. Continue your excursion with an orientation drive through Mumbai passing prominent landmarks such as Flora Fountain, the university and Victoria Terminus. The latter is a most remarkable railway station, inspired by St Pancras Station in London. It was built during Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee year and is an extraordinary conglomeration of domes, spires, Corinthian columns and minarets in a style described by journalist James Cameron as Victorian- Gothic-Saracenic-Italianate-Oriental-St Pancras-Baroque. The first train in India left from this station in 1853; today, half-a-million commuters use the station every day. At theMani Bhawan Gandhi Museum you’ll visit the site that was Mahatma Gandhi’s Bombay base between 1917 and 1934. A series of tiny dioramas tell Gandhi’s life story. -

Auction Details Seller Details

95476 Auction Details Auction No MSTC/WRO/ORDNANCE FACTORY/2/DEHUROAD/1516/851[95476] Opening Date & Time 23042015::12:00:00 Closing Date & Time 23042015::18:00:00 Inspection From Date 08042015 Inspection Closing Date 22042015 Seller Details Seller/Company Name ORDNANCE FACTORY Location DEHUROAD Street DEHUROAD City PUNE 412101 Country INDIA Telephone 02027670205 Fax 0207671616 Email [email protected] Contact Person R.M.BENDRE LOT NO[PCB GRP]/LOT NAME LOT DESC QUANTITY ED/(ST/VAT) LOCATION Lot No: 265 L.F.NO.9914237894 MILD STEEL SCRAP CLASSC INCLUDING VARIOUS UNSERVICED CYLINDERS, LIDS, ORD.FACTORY, DEHU ROAD, RINGS CUTTINGS, PUNCHINGS END PIECES AND RUSTY STEEL BOXES SORTS AND 20 MT 12.5 / 5% SIZES. PUNE. State :Maharashtra Lot Name: MILD STEEL SCRAP CLASS C Lot No: 266 L.F.NO.0799983226 ORD.FACTORY, M.S.DRUM SORTS AND SIZES, CLOSE/OPEN MOUTH, RUSTY, DAMAGED WITH/WITHOUT DEHU ROAD, 1000 NO 12.5 / 5% LID AND DRIED WITH PARTIAL PINT. PUNE. State :Maharashtra Lot Name: M.S.DRUM SORTS & SIZES Lot No: 269 L.F.NO.9914232973 ORD.FACTORY, DEHU ROAD, LID FOR DRUM 600 MM DIA RUSTY / M.S. DRUM LID FOR 200/205 LTR CAP. 300 NO 12.5 / 5% PUNE. State :Maharashtra Lot Name: LID FOR DRUM 600 MM Lot No: 270 L.F.NO.2225109999 ORD.FACTORY, DEHU ROAD, TIMBER FIRE WOOD SCRAP. 15000 KG 12.5 / 5% PUNE. State :Maharashtra Lot Name: TIMBER FIRE WOOD SCRAP Lot No: 271 L.F.NO.9914221869 ORD.FACTORY, DEHU ROAD, ALUMINIUM SCRAP (TURNING & BORING ONLY). -

Preparatory Survey on the Urban Railway Project in Pune City

PUNE MUNICIPAL CORPORATION PUNE, MAHARASHTRA, INDIA PREPARATORY SURVEY ON THE URBAN RAILWAY PROJECT IN PUNE CITY FINAL REPORT JUNE 2013 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. OS TOSHIBA CORPORATION JR(先) INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT CENTER OF JAPAN INC. 13-067 PUNE MUNICIPAL CORPORATION PUNE, MAHARASHTRA, INDIA PREPARATORY SURVEY ON THE URBAN RAILWAY PROJECT IN PUNE CITY FINAL REPORT JUNE 2013 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. TOSHIBA CORPORATION INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT CENTER OF JAPAN INC. Preparatory Survey on the Urban Railway Project in Pune City Final Report TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Abbreviations Page Chapter 1 Implementation Policy 1.1 Basic Policy of the Study ...................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1.1 Background of the Study............................................................................................... 1-1 1.1.2 Purpose of this Study..................................................................................................... 1-2 1.1.3 Approach to Conducting the Study ............................................................................... 1-2 1.1.4 Study Methodology ....................................................................................................... 1-7 1.1.5 Selection of Study Team Members and Schedule ......................................................... 1-9 1.2 Target Area of this Study ................................................................................................... -

Sl No. District Taluka / Tehsil Name Village Name 1 Pune Mawal

Land Schedule Taluka / Tehsil Gat No./ Survey Area Area Sl No. District Village Name Name No. (in Sqm.) (in Ha.) 1 Pune Mawal Parandwadi 264 19808.864 1.9810 265 9326.961 0.9330 266 6468.980 0.6470 267 9803.920 0.9800 268 19488.093 1.9490 273 30220.000 3.0220 275 25485.000 2.5485 276 11240.000 1.1240 Rasta 2305.000 0.2305 32 51920.000 5.1920 33 1420.000 0.1420 259 15160.000 1.5160 258 7355.000 0.7355 257 9115.000 0.9115 255 17795.000 1.7795 254 1425.000 0.1425 253 1455.000 0.1455 248 9530.000 0.9530 252 1485.000 0.1485 251 375.000 0.0375 250 480.000 0.0480 249 475.000 0.0475 245 1820.000 0.1820 244 765.000 0.0765 240 3845.000 0.3845 241 455.000 0.0455 239 570.000 0.0570 238 1320.000 0.1320 237 8340.000 0.8340 236 920.000 0.0920 235 980.000 0.0980 234 1540.000 0.1540 233 6110.000 0.6110 Page 1 of 71 Taluka / Tehsil Gat No./ Survey Area Area Sl No. District Village Name Name No. (in Sqm.) (in Ha.) 232 1430.000 0.1430 231 10040.000 1.0040 230 16245.000 1.6245 256 7740.000 0.7740 229 21345.000 2.1345 228 3175.000 0.3175 227 1820.000 0.1820 226 18620.000 1.8620 225 8230.000 0.8230 224 1260.000 0.1260 214 6555.000 0.6555 215 5665.000 0.5665 216 4230.000 0.4230 217 4235.000 0.4235 218 13820.000 1.3820 212 3135.000 0.3135 209 20.000 0.0020 207 7055.000 0.7055 202A 7145.000 0.7145 201 11305.000 1.1305 170 9270.000 0.9270 169 8690.000 0.8690 159 10690.000 1.0690 160 4590.000 0.4590 Total 46.5115 Page 2 of 71 Taluka / Tehsil Gat No./ Survey Area Area Sl No.