Artificial Intelligence,” States That the Ending Is “The Film’S Most Sentimental Moment, Yet It’S Questionable Whether It Involves Any Real People at All” (220)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Isekai No Seikishi Monogatari

Tenchi Muyo! War on Geminar ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Intro: The Tenchi Muyo series is huge, and the canonicity may not be particularly clear to the uninitiated. This part of the series and Jump take place after the start of the main timeline and GXP. The story takes place in the world of Germinar, and you no longer need to worry about multiversal goddesses, planet-busting trees, and other such things for your stay. Following Masaki Tenchi's half-brother Masaki Kenshi, this story would normally start with the attack on the Swan (a flying landship), but it now starts with the arrival of Kenshi at the Summoning Ruins still not long before. This world is bathed in high levels of a relatively nondescript energy. This prevents nearly all technology from working above a certain altitude in addition to making others extremely sick, eventually to the point of death, should they stay in these areas. Even the pilots of this world's holy mecha cannot enter these areas or they both will shutdown. This has lead to the higher lands being covered in mostly normal flora and the occasional super flora. The people of this world have coped with this by building their cities lower than the effected areas and carving out valleys for travel. Take your pick of the purchases available below with the 1,000CP (choice points) provided, and be sure to read the notes. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Origins: How you start in this world. Your age is 15 and your gender stays the same. Both can be changed for 100CP. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Drop-In (Free) – You just show up in the Holy Land one day. -

Disney Pinocchio Pdf, Epub, Ebook

LEVEL 3: DISNEY PINOCCHIO PDF, EPUB, EBOOK M Williams | 24 pages | 21 Feb 2012 | Pearson Education Limited | 9781408288610 | English | Harlow, United Kingdom Level 3: Disney Pinocchio PDF Book The Fairy cryptically responds that all inhabitants of the house, including herself, are dead, and that she is waiting for her coffin to arrive. Just contact our customer service department with your return request or you can initiate a return request through eBay. Reviews No reviews so far. The article or pieces of the original article was at Disney Magical World. Later, she reveals to Pinocchio that his days of puppethood are almost over, and that she will organize a celebration in his honour; but Pinocchio is convinced by his friend, Candlewick Lucignolo to go for Land of Toys Paese dei Balocchi a place who the boys don't have anything besides play. After Pinocchio find her tombstone instead of house she appears later in different forms including a giant pigeon. The main danger are the rocks. They can't hurt you, but if they grab you they'll knock you to a lower level. After finishing this last routine you beat the level. Il giorno sbagliato. By ryan level Some emoji powers don't change As the player levels Up, the emojis are available for fans to play 6 with a blue Emoji with The article or pieces of the original article was at Disney Magical World. Venduto e spedito da IBS. The order in which you should get the pages is: white, yellow, blue and red. To finish the level, you have to kill all the yellow moths. -

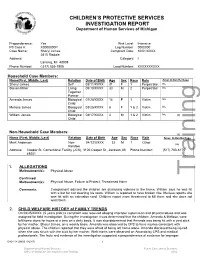

James CPS Investigation Report

CHILDREN’S PROTECTIVE SERVICES INVESTIGATION REPORT Department of Human Services of Michigan Preponderance: Yes Risk Level: Intensive PS Case #: X0000000P Log Number: 0000000 Case Name: Sheryl James Complaint Date: 10/01/XXXX 2815 Risdale Address: Category: I Lansing, MI 48909 Phone Number: ( 517) 555-1908 Load Number: XXXXXXXXXX Household Case Members: Name(First, Middle, Last) Relation Date of Birth Age Sex Race Role Amer.Indian Heritage Sheryl James Self 03/11/XXXX 31 F 1 Perpetrator No Steven Miller Living 05/10/XXXX 33 M 2 Perpetrator No Together Partner Amanda James Biological 07/28/XXXX 14 F 1 Victim No Child Melissa James Biological 03/25/XXXX 8 F 1 & 2 Victim No Child William James Biological 04/17/XXXX 4 M 1 & 2 Victim No Child Non-Household Case Members: Name (First, Middle, Last) Relation Date of Birth Age Sex Race Role Amer. Indian Heritage Mark Anderson Non- 04/12/XXXX 32 M 1 Other No Relative Address: Cooper St. Correctional Facility (JCS), 3100 Cooper St., Jackson, MI Phone Number: (517) 780-6175 49201 1. ALLEGATIONS Maltreatment(s): Physical Abuse Training Confirmed Maltreatment(s): Physical Abuse, Failure to Protect, Threatened Harm Comments: Complainant advised the children are disclosing violence in the home. William says he was hit with a bat for not cleaning his room. William is reported to have broken ribs. Melissa reports she was hit with an extension cord. Children report mom threatened to kill them and she does not want them. 2. CHILD WELFARE HISTORY of FAMILY TRENDS On 02/25/XXXX, (5 years prior) a complaint was received alleging improper supervision and physical abuse and was assigned for field investigation. -

Ebook Download the Adventures of Pinocchio Ebook

THE ADVENTURES OF PINOCCHIO PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Carlo Collodi, Roberto Innocenti | 191 pages | 01 Sep 2005 | Creative Edition | 9781568461908 | English | Mankato, MN, United States The Adventures of Pinocchio PDF Book How it happened that Mastro Cherry, carpenter, found a piece of wood that wept and laughed like a child. Beyond hard work, he learns the virtue of self-sacrifice: on hearing that the Fairy is ill and destitute, Pinocchio sends her the money he is saving for new clothes for himself, his generosity winning him not just her forgiveness but the humanity he covets. Namespaces Article Talk. Theatrical release poster. French forces commanded by Napoleon Bonaparte had invaded Italy back in , bringing the peninsula under French control until After this latest scrape, the Fairy, with whom Pinocchio is now living, warns him against further misbehavior. Chairs for the students performing. During one job, he encounters Candlewick again, still a donkey and dying from overwork. This character clearly shows that when he is not honest with himself or others there are consequences. When he neglects his books in favor of idle entertainments, he suffers such misfortunes as being abducted, jailed, or transformed into a donkey. The Adventures of Pluto Nash. The Adventures of Don Quixote. This moral tale centers around Geppetto, a woodcarver, and his puppet Pinocchio who wants to become a real human being. Do not hit me so hard! October 16, Setting off for school, Pinocchio is almost immediately tempted to forego his duty by attending a puppet show. The Adventures of Pinocchio by Carlo Collodi. At this third lie his nose grew to such an extraordinary length that poor Pinocchio could not move in any direction. -

Views That Barnes Has Given, Wherein

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2018 Darker Matters: Racial Theorizing through Alternate History, Transhistorical Black Bodies, and Towards a Literature of Black Mecha in the Science Fiction Novels of Steven Barnes Alexander Dumas J. Brickler IV Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES DARKER MATTERS: RACIAL THEORIZING THROUGH ALTERNATE HISTORY, TRANSHISTORICAL BLACK BODIES, AND TOWARDS A LITERATURE OF BLACK MECHA IN THE SCIENCE FICTION NOVELS OF STEVEN BARNES By ALEXANDER DUMAS J. BRICKLER IV A Dissertation Submitted to the Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2018 Alexander Dumas J. Brickler IV defended this dissertation on April 16, 2018. The members of the supervisory committee were: Jerrilyn McGregory Professor Directing Dissertation Delia Poey University Representative Maxine Montgomery Committee Member Candace Ward Committee Member Dennis Moore Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Foremost, I have to give thanks to the Most High. My odyssey through graduate school was indeed a long night of the soul, and without mustard-seed/mountain-moving faith, this journey would have been stymied a long time before now. Profound thanks to my utterly phenomenal dissertation committee as well, and my chair, Dr. Jerrilyn McGregory, especially. From the moment I first perused the syllabus of her class on folkloric and speculative traditions of Black authors, I knew I was going to have a fantastic experience working with her. -

PINOCCHIO! by Dan Neidermyer

PINOCCHIO! By Dan Neidermyer Copyright © MCMXCIV by Dan Neidermyer, All Rights Reserved ISBN: 978-1-61588-124-6 CAUTION: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that this Work is subject to a royalty. This Work is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America and all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations, whether through bilateral or multilateral treaties or otherwise, and including, but not limited to, all countries covered by the Pan-American Copyright Convention, the Universal Copyright Convention and the Berne Convention. RIGHTS RESERVED: All rights to this Work are strictly reserved, including professional and amateur stage performance rights. Also reserved are: motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video or sound recording, all forms of mechanical or electronic reproduction, such as CD-ROM, CD-I, DVD, information and storage retrieval systems and photocopying, and the rights of translation into non-English languages. PERFORMANCE RIGHTS AND ROYALTY PAYMENTS: All amateur and stock performance rights to this Work are controlled exclusively by Heuer Publishing. No amateur or stock production groups or individuals may perform this play without securing license and royalty arrangements in advance from Heuer Publishing. Questions concerning other rights should be addressed to Heuer Publishing. Royalty fees are subject to change without notice. Professional and stock fees will be set upon application in accordance with your producing circumstances. Any licensing requests and inquiries relating to amateur and stock (professional) performance rights should be addressed to Heuer Publishing. Royalty of the required amount must be paid, whether the play is presented for charity or profit and whether or not admission is charged. -

It's a Conspiracy

IT’S A CONSPIRACY! As a Cautionary Remembrance of the JFK Assassination—A Survey of Films With A Paranoid Edge Dan Akira Nishimura with Don Malcolm The only culture to enlist the imagination and change the charac- der. As it snows, he walks the streets of the town that will be forever ter of Americans was the one we had been given by the movies… changed. The banker Mr. Potter (Lionel Barrymore), a scrooge-like No movie star had the mind, courage or force to be national character, practically owns Bedford Falls. As he prepares to reshape leader… So the President nominated himself. He would fill the it in his own image, Potter doesn’t act alone. There’s also a board void. He would be the movie star come to life as President. of directors with identities shielded from the public (think MPAA). Who are these people? And what’s so wonderful about them? —Norman Mailer 3. Ace in the Hole (1951) resident John F. Kennedy was a movie fan. Ironically, one A former big city reporter of his favorites was The Manchurian Candidate (1962), lands a job for an Albu- directed by John Frankenheimer. With the president’s per- querque daily. Chuck Tatum mission, Frankenheimer was able to shoot scenes from (Kirk Douglas) is looking for Seven Days in May (1964) at the White House. Due to a ticket back to “the Apple.” Pthe events of November 1963, both films seem prescient. He thinks he’s found it when Was Lee Harvey Oswald a sleeper agent, a “Manchurian candidate?” Leo Mimosa (Richard Bene- Or was it a military coup as in the latter film? Or both? dict) is trapped in a cave Over the years, many films have dealt with political conspira- collapse. -

Read an Excerpt

Excerpt Terms & Conditions This excerpt is available to assist you in the play selection process. You may view, print and download any of our excerpts for perusal purposes. Excerpts are not intended for performance, classroom or other academic use. In any of these cases you will need to purchase playbooks via our website or by phone, fax or mail. A short excerpt is not always indicative of the entire work, and we strongly suggest reading the whole play before planning a production or ordering a cast quantity of scripts. Family Plays Pinocchio Book and lyrics by Patty Carver Music by Patty Carver and Leo P. Carusone Based on the story by Carlo Collodi © Family Plays Pinocchio Interactive musical. Book and lyrics by Patty Carver. Music by Patty Carver and Leo P. Carusone. Based on the story by Carlo Collodi. Cast: 4 to 6m., 1 to 2w. (2 to 4+ either gender optional). Meet the Blue Fairy as she leads us on a magical journey through this retelling of the classic story. One day, Geppetto, the poor, old toymaker, finds an extraordinary piece of talking wood. He brings it home and decides to make it into a puppet named Pinocchio. Disagreeable Pinocchio immediately gets into trouble and learns important lessons. When he bullies a little cricket, he’s reminded to respect others. When he runs away, gets lost and tries to find his way home, he’s reminded of the wonderful life he had with Geppetto. When Pinocchio decides he no longer wants to be a puppet but a real boy, the Blue Fairy steps in and reminds him that if he wants to be real, he has to be good. -

Llllllllllll~Ll1lllllllll~~781894 814928 Sample File CHAPTER ONE: BASICS

I- I -J Sample file -4k 9 ~~llllllllllll~ll1lllllllll~~781894 814928 Sample file CHAPTER ONE: BASICS ...................... 4 M12 General Longstreet ................67 Infantry Walker Mk VI1 Cavalier ...... 68 Fantasy ............................................. 5 Infantry Walker Mk XI1 Roundhead . 69 Steampunk ....................................... 5 PzK IV Loki ..................................... 70 Alternate History ............................... 5 PzK V Valkurie ................................ 71 Modern Day/Near Future .................. 5 PzK VI Donner ................................ 72 Far Future ......................................... 5 PzK VI1 Uller ................................... 73 Marc A . Vezina. Senior Editor Space Opera .................................... 6 Gear Krieg Modern ............................. 74 Alistair Gillies. Contributor Espionage ........................................ 6 M1AI Abrams Mechatank .............. 77 Horror ............................................... 6 M3A1 Bradley IFW ......................... 78 Christian Schaller. Contributor Sentai ............................................... 6 M1025 HMMWV ............................. 79 Campaign Themes ............................... 6 The texts in Chapter 1. 5 and 6 are RT-72 Mechatank ........................... 80 Action ............................................... 6 R-57 SCUD Mobile Launcher .........81 based on the mecha rules texts cre- Adventure ............................. Phoenix Rising ................................... -

We Offer Our Customers Industry-Leading Technology

POWERFUL NEWS FOR EVENT INDUSTRY PARTNERS THE MAIN What exactly are we selling? We offer our customers industry-leading technology. But we’re not just about the “machines” we deliver to our event sites. TM VOL. 3 / ISSUE 2 2004 THE INSIDER We’re also about the service. We burn a great deal of midnight oil putting together the perfect proposal or coordinating the delivery, setup and operation of our equipment. But no matter how we plan, events don’t always go as intended. So how do we handle the 4 am phone call from the movie set needing more power, or a change in the shooting schedule due to rain? Naturally, we take care of these requests with a sense of urgency, calm and professionalism. Sure, technology and service are important components of the event services business. But I think our success is tied even more to “intangibles” like job-specific knowledge and building personal relationships. Whenever we deliver more equipment to a customer or make our rounds, use the opportunity to listen, ask questions, offer creative solutions, and make sure KOHLER ‘ULTIMATE TEAM PLAYER’ we’re as proactive as possible. Believe we’re providing the best service in the business — but always look for ways to FOR HOLOCAUST TRIBUTE learn more and to meet more people. That means many loyal customers to us. And that’s how we as a company can Imagine increasing the guest list by a best compete — by staying ahead of the The event may be nationally couple thousand just a week before a big event. -

Script Teatring Fes Fai Egin PINOCCHIO

think haz fais Script teatring fes fai egin PINOCCHIO CHARACTERS GEPPETTO PINOCCHIO SOFIA, THE FAIRY GODMOTHER STROMBOLI TRACK * This symbol indicates the Track number on the album Canta y Haz Teatring. The album can also be found on our website www.recursosweb.com All rights whatsoeverin this script are strictly reserved. 2 PINOCCHIO SCENE 1 Some music is heard, the curtain opens. We see a puppet workshop full of wooden toys. Geppetto enters to the scene carrying a wooden trunk and he placed on a chair. Geppetto is tired. Geppetto: (Looking at his puppets) Hello, my little friends. I’m here. He puts his coat and hat on a chair. Geppetto: Look, look what I found in the woods, eh? A nice piece of wood. Grabbing the sleeve of his coat, greeting him as if it were a person. Geppetto: Hello my new friend, how are you? Geppetto goes to sit down on another chair, putting the piece of wood in front of it, but he falls onto the floor. Geppetto: Auuuu! We can hear a child giggle. Geppetto: What? Who is laughing? We hear the laughter again and Geppetto realizes that it was the tree trunk. Geppetto: Oh! It’s you! My new friend. I see!!! You like to play like a child. Mmmmm, let me see. Yes! You will be a child! Geppetto puts the wood inside a box and starts working with it. There is some music while Geppetto is working. Geppetto makes a wooden puppet. (Looking inside the box) Oh! Perfect! Now, the strings. (Geppetto puts the strings on the puppet) Perfect! You’re ready. -

Once Upon a Time There Was a Piece of Wood. It Wasn't a Fine Type of Wood

Once upon a time there was a piece of wood. It wasn’t a fine type of wood, the kind that’s used to make toys or furniture for the sitting room, but a cheap wood, good for burning in the fireplace. Old Geppetto, who worked as a carpenter, decided to use it to make the puppet that he had long wished for. The next day, Geppetto almost fainted when he saw Pinocchio skip around the house. “Dad, I want to go to school!” trilled the puppet in a voice that sounded like little silver bells. As he didn’t have a penny in his pockets, Geppetto rushed to sell the only coat he had to buy a spelling book, and sent him off to school. Along the way, Pinocchio heard a music of pipes and drums and discovered… a travelling show, no less! “Pinocchio, go to school!” said his When he had finished, the man rested his puppet conscience, but he on a shelf and said, admiringly: “Ah, wouldn’t it be wouldn’t listen and he nice if he was a real boy? I’ll call him “Pinocchio”. sold his spelling book In the middle of the night, the good Blue-Haired to buy a ticket for Fairy appeared in his house and, with her prodigious the puppet show. magic wand, she gave life to Pinocchio. 2 As soon as the puppets saw Pinocchio, they Seeing him in tears invited him up on stage. While Pinocchio, singing and having listened and dancing, was reaping a great success, to his story, the puppeteer, Mangiafuoco, a large man the man, who with a long beard as black as ink, deep down had rubbed his hands together a tender heart, at the sight of coins gave him five raining onto the shiny gold stage from coins and said: the enthusiastic ”Take these audience.