Genocide Or Terrorism?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boko Haram Beyond the Headlines: Analyses of Africa’S Enduring Insurgency

Boko Haram Beyond the Headlines: Analyses of Africa’s Enduring Insurgency Editor: Jacob Zenn Boko Haram Beyond the Headlines: Analyses of Africa’s Enduring Insurgency Jacob Zenn (Editor) Abdulbasit Kassim Elizabeth Pearson Atta Barkindo Idayat Hassan Zacharias Pieri Omar Mahmoud Combating Terrorism Center at West Point United States Military Academy www.ctc.usma.edu The views expressed in this report are the authors’ and do not necessarily reflect those of the Combating Terrorism Center, United States Military Academy, Department of Defense, or U.S. Government. May 2018 Cover Photo: A group of Boko Haram fighters line up in this still taken from a propaganda video dated March 31, 2016. COMBATING TERRORISM CENTER ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Director The editor thanks colleagues at the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point (CTC), all of whom supported this endeavor by proposing the idea to carry out a LTC Bryan Price, Ph.D. report on Boko Haram and working with the editor and contributors to see the Deputy Director project to its rightful end. In this regard, I thank especially Brian Dodwell, Dan- iel Milton, Jason Warner, Kristina Hummel, and Larisa Baste, who all directly Brian Dodwell collaborated on the report. I also thank the two peer reviewers, Brandon Kend- hammer and Matthew Page, for their input and valuable feedback without which Research Director we could not have completed this project up to such a high standard. There were Dr. Daniel Milton numerous other leaders and experts at the CTC who assisted with this project behind-the-scenes, and I thank them, too. Distinguished Chair Most importantly, we would like to dedicate this volume to all those whose lives LTG (Ret) Dell Dailey have been afected by conflict and to those who have devoted their lives to seeking Class of 1987 Senior Fellow peace and justice. -

Othering Terrorism: a Rhetorical Strategy of Strategic Labeling

Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal Volume 13 Issue 2 Rethinking Genocide, Mass Atrocities, and Political Violence in Africa: New Directions, Article 9 New Inquiries, and Global Perspectives 6-2019 Othering Terrorism: A Rhetorical Strategy of Strategic Labeling Michael Loadenthal Miami University of Oxford Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp Recommended Citation Loadenthal, Michael (2019) "Othering Terrorism: A Rhetorical Strategy of Strategic Labeling," Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal: Vol. 13: Iss. 2: 74-105. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5038/1911-9933.13.2.1704 Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp/vol13/iss2/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Othering Terrorism: A Rhetorical Strategy of Strategic Labeling Michael Loadenthal Miami University of Oxford Oxford, Ohio, USA Reel Bad Africans1 & the Cinema of Terrorism Throughout Ridley Scott’s 2002 film Black Hawk Down, Orientalist “othering” abounds, mirroring the simplistic political narrative of the film at large. In this tired script, we (the West) are fighting to help them (the East Africans) escape the grip of warlordism, tribalism, and failed states through the deployment of brute counterinsurgency and policing strategies. In the film, the US soldiers enter the hostile zone of Mogadishu, Somalia, while attempting to arrest the very militia leaders thought to be benefitting from the disorder of armed conflict. -

Assessment of States' Response to the September

i ASSESSMENT OF STATES’ RESPONSE TO THE SEPTEMBER 11, 2001TERROR ATTACK IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA AND THE NIGERIAN PERSPECTIVE BY EMEKA C. ADIBE REG NO: PG/Ph.D/13/66801 UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA FACULTY OF LAW DEPARMENT OF INTERNATIONAL LAW AND JURISPRUDENCE AUGUST, 2018 ii TITLE PAGE ASSESSMENT OF STATES’ RESPONSETO THE SEPTEMBER 11, 2001TERROR ATTACK IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA AND THE NIGERIAN PERSPECTIVE BY EMEKA C. ADIBE REG. NO: PG/Ph.D/13/66801 SUBMITTED IN FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN LAW IN THE DEPARMENT OF INTERNATIONAL LAW AND JURISPRUDENCE, FACULTY OF LAW, UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA SUPERVISOR: PROF JOY NGOZI EZEILO (OON) AUGUST, 2018 iii CERTIFICATION This is to certify that this research was carried out by Emeka C. Adibe, a post graduate student in Department of International law and Jurisprudence with registration number PG/Ph.D/13/66801. This work is original and has not been submitted in part or full for the award of any degree in this or any other institution. ---------------------------------- ------------------------------- ADIBE, Emeka C. Date (Student) --------------------------------- ------------------------------- Prof. Joy Ngozi Ezeilo (OON) Date (Supervisor) ------------------------------- ------------------------------- Dr. Emmanuel Onyeabor Date (Head of Department) ------------------------------------- ------------------------------- Prof. Joy Ngozi Ezeilo (OON) Date (Dean, Faculty of Law) iv DEDICATION To all Victims of Terrorism all over the World. v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Gratitude is owned to God in and out of season and especially on the completion of such a project as this, bearing in mind that a Ph.D. research is a preserve of only those privileged by God who alone makes it possible by his gift of good health, perseverance and analytic skills. -

Weaponization of Water in a Changing Climate Marcus D

EPICENTERS OF CLIMATE AND SECURITY: THE NEW GEOSTRATEGIC LANDSCAPE OF THE ANTHROPOCENE June 2017 Edited by: Caitlin E. Werrell and Francesco Femia Sponsored by: In partnership with: WATER WEAPONIZATION THE WEAPONIZATION OF WATER IN A CHANGING CLIMATE Marcus D. King1 and Julia Burnell 2,3 Water stress across the Middle East and Africa is providing an opportunity for subnational extremist organizations waging internal conflict to wield water as a weapon. The weaponization of water also drives conflict that transcends national borders, creating international ripple effects that contribute to a changing geostrategic landscape. Climate change-driven water stress in arid and semi-arid countries is a growing trend. This stress includes inadequacies in water supply, quality, and accessibility.4 These countries are consistently experiencing chronically dry climates and unpredictable, yet prevalent, droughts. Predicted future climate impacts include higher temperatures, longer dry seasons, and increased variability in precipitation. In the coming decades, these factors will continue to stress water resources in most arid regions.5 It is accepted wisdom that parties generally cooperate over scarce water resources at both the international and subnational levels, with a very few notable exceptions that have resulted in internal, low-intensity conflict.6 However, tensions have always existed: the word rivalry comes from the Latin word rivalus, meaning he who shares a river.7 Rivalry is growing at the sub-state level, leading to intractable conflicts. Social scientists have long observed a correlation between environmental scarcity and subnational conflict that is persistent and diffuse.8 Disputes over limited natural resources have played at least some role in 40 percent of all intrastate conflicts in the last 60 years.9 The Center for Climate and Security www.climateandsecurity.org EPICENTERS OF CLIMATE AND SECURITY 67 Recent scholarly literature and intelligence forecasts have also raised doubts that water stress will continue to engender more cooperation than conflict. -

Examining the Boko Haram Insurgency in Northern

Global Journal of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences Vol.3, No.8, pp.32-45, August 2015 ___Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) EXAMINING THE BOKO HARAM INSURGENCY IN NORTHERN NIGERIA AND THE QUEST FOR A PERMANENT RESOLUTION OF THE CRISIS Joseph Olukayode Akinbi (Ph.D) Department of History, Adeyemi Federal University of Education P.M.B 520, Ondo, Ondo State, Nigeria ABSTRACT: The state of insecurity engendered by Boko Haram insurgency in Nigeria, especially in the North-Eastern part of the country is quiet worrisome, disheartening and alarming. Terrorist attacks of the Boko Haram sect have resulted in the killing of countless number of innocent people and wanton destruction of properties that worth billions of naira through bombings. More worrisome however, is the fact that all the efforts of the Nigerian government to curtail the activities of the sect have not yielded any meaningful positive result. Thus, the Boko Haram scourge remains intractable to the government who appears helpless in curtailing/curbing their activities. The dynamics and sophistication of the Boko Haram operations have raised fundamental questions about national security, governance issue and Nigeria’s corporate existence. The major thrust of this paper is to investigate the Boko Haram insurgency in Northern Nigeria and to underscore the urgent need for a permanent resolution of the crisis. The paper argues that most of the circumstances that led to this insurgency are not unconnected with frustration caused by high rate of poverty, unemployment, weak governance, religious fanaticism among others. It also addresses the effects of the insurgency which among others include serious threat to national interest, peace and security, internal population displacement, violation of fundamental human rights, debilitating effects on the entrenchment of democratic principles in Nigeria among others. -

The Age of Hyperconflict and the Globalization-Terrorism Nexus: a Comparative Study of Al Shabaab in Somalia and Boko Haram in Nigeria

The Age of Hyperconflict and the Globalization-Terrorism Nexus: A Comparative Study of Al Shabaab in Somalia and Boko Haram in Nigeria By Vasti Botma Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Political Science) in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Mr. Gerrie Swart December 2015 The financial assistance of the National Research Foundation (NRF) towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at, are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the NRF. Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own original work, that I am the authorship owner thereof (unless to the extent explicitly otherwise stated) and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. December 2015 Copyright © 2015 Stellenbosch University of Stellenbosch All rights reserved i Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract Globalization has radically changed the world we live in; it has enabled the easy movement of people, goods and money across borders, and has facilitated improved communication. In a sense it has made our lives easier, however the same facets that have improved the lives of citizens across the globe now threatens them. Terrorist organizations now make use of these same facets of globalization in order to facilitate terrorist activity. This thesis set out to examine the extent to which globalization has contributed to the creation of a permissive environment in which terrorism has flourished in Somalia and northern Nigeria respectively, and how it has done so. -

Fragility and Climate Risks in Nigeria

FRAGILITY AND CLIMATE RISKS IN NIGERIA SEPTEMBER 2018 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Ashley Moran, Clionadh Raleigh, Joshua W. Busby, Charles Wight, and Management Systems International, A Tetra Tech Company. FRAGILITY AND CLIMATE RISKS IN NIGERIA Contracted under IQC No. AID-OAA-I-13-00042; Task Order No. AID-OAA-TO-14-00022 Fragility and Conflict Technical and Research Services (FACTRS) DISCLAIMER The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acronyms...................................................................................................................... iv Executive Summary ...................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 3 Climate Risks ................................................................................................................. 3 Fragility Risks ................................................................................................................. 7 Key Areas of Concern ........................................................................................................................ 8 Key Area of Improvement ................................................................................................................ -

Transformations in United States Policy Toward Syria Under Bashar

Nova Southeastern University NSUWorks Department of Conflict Resolution Studies Theses CAHSS Theses and Dissertations and Dissertations 1-1-2017 Transformations in United States Policy toward Syria Under Bashar Al Assad A Unique Case Study of Three Presidential Administrations and a Projection of Future Policy Directions Mohammad Alkahtani Nova Southeastern University, [email protected] This document is a product of extensive research conducted at the Nova Southeastern University College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences. For more information on research and degree programs at the NSU College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences, please click here. Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/shss_dcar_etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Share Feedback About This Item NSUWorks Citation Mohammad Alkahtani. 2017. Transformations in United States Policy toward Syria Under Bashar Al Assad A Unique Case Study of Three Presidential Administrations and a Projection of Future Policy Directions. Doctoral dissertation. Nova Southeastern University. Retrieved from NSUWorks, College of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences – Department of Conflict Resolution Studies. (103) https://nsuworks.nova.edu/shss_dcar_etd/103. This Dissertation is brought to you by the CAHSS Theses and Dissertations at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Department of Conflict Resolution Studies Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. -

The Rise of Boko Haram

Master Thesis Political Science: International Relations The rise of Boko Haram A Social Movement Theory Approach Author: Iris Visser Student Number: 5737508 MA Research Project Political Science: International Relations Supervisor: Dr. Said Rezaeiejan Second reader: Dr. Ursula Daxecker Date: 25 June 2014 1 Master Thesis Political Science: International Relations The rise of Boko Haram A Social Movement Theory Approach 2 3 Table of contents Political map of Nigeria 6 I. Introduction 7 II. Theoretical framework and literature review 13 III. Methodology 34 Variables 34 Methodological issues 34 Operationalization 35 IV. Background of Nigeria 43 V. The rise and evolution of Boko Haram 51 VI. United States- Nigeria cooperation concerning counterterrorism 59 VII. A political process perspective 64 VIII. A relative deprivation perspective 75 IX. A resource mobilization perspective 91 X. A framing perspective 108 XI. Conclusion 122 Bibliography 127 Appendix: timeline of Boko Haram attacks 139 Number of Boko Haram attacks and resulting deaths 2010-2014 per quarter 139 Timeline of Boko Haram attacks 2010-2014 140 4 5 Map of Nigeria 6 I. Introduction Like many postcolonial states, Nigeria has a turbulent history. The country is plagued by all kinds of violence. There has been civil war,1 crime rates are high,2 communal violence is common, as is sectarian violence3 — and, often along the same lines, political violence4 — while in the south an added problem are conflicts concerning oil.5 One of the biggest problems Nigeria faces today, is that of radical Islamic violence in the north of the country. Whereas communal violence has long been an issue, the rise of radical Islamic groups such as Boko Haram, who function more like a terrorist organization, is relatively new (as it is in most parts of the world). -

Igbos: the Hebrews of West Africa

Igbos: The Hebrews of West Africa by Michelle Lopez Wellansky Submitted to the Board of Humanities School of SUY Purchase in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts Purchase College State University of New York May 2017 Sponsor: Leandro Benmergui Second Reader: Rachel Hallote 1 Igbos: The Hebrews of West Africa Michelle Lopez Wellansky Introduction There are many groups of people around the world who claim to be Jews. Some declare they are descendants of the ancient Israelites; others have performed group conversions. One group that stands out is the Igbo people of Southeastern Nigeria. The Igbo are one of many groups that proclaim to make up the Diasporic Jews from Africa. Historians and ethnographers have looked at the story of the Igbo from different perspectives. The Igbo people are an ethnic tribe from Southern Nigeria. Pronounced “Ee- bo” (the “g” is silent), they are the third largest tribe in Nigeria, behind the Hausa and the Yoruba. The country, formally known as the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is in West Africa on the Atlantic Coast and is bordered by Chad, Cameroon, Benin, and Niger. The Igbo make up about 18% of the Nigerian population. They speak the Igbo language, which is part of the Niger-Congo language family. The majority of the Igbo today are practicing Christians. Though they identify as Christian, many consider themselves to be “cultural” or “ethnic” Jews. Additionally, there are more than two million Igbos who practice Judaism while also reading the New Testament. In The Black -

Extremism & Terrorism

Chad: Extremism & Terrorism On April 20, 2021, President Idriss Deby—Chad’s president for more than 30 years—died due to injuries sustained in battle fighting against the Libya-based Islamist rebel group, Front for Change and Concord in Chad (FACT), in northern Chad. Deby, who was declared the winner of the presidential election the day prior, often joined soldiers on the battlefront. On April 11, 2021, hundreds of FACT forces launched an incursion into the north of Chad to protest the April 11th presidential election. The group attacked a border post at Zouarke. However, no casualties were reported. Following the Zouarke ambush, Deby joined Chadian soldiers to repel FACT forces from advancing on N’Djamena. On April 17, two FACT convoys clashed with government forces on the way to N’Djamena, killing five Chadian soldiers and injuring 36 others. Among those injured was Deby. Deby’s son, Mahamat Kaka, was named interim president by a transitional council of military officers on April 20. (Sources: Reuters, France 24, Al Jazeera, Reuters, Bloomberg) On February 15, 2021, leaders of the G5 Sahel—Chad, Burkina Faso, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger—attended a two-day summit in N’Djamena. At the summit, Deby announced that more than 1,200 troops would be deployed to combat extremist groups on the Sahel border zone between Niger, Mali, and Burkina Faso. Deby urged the international community to increase its funds for development to prevent the continued rise of terrorism and reasons for radicalization in Chad. Chad’s increase in deployment comes a month after French President Emmanuel Macron suggested that France may “adjust” its military commitment in the Sahel following attacks that increased the number of French combat deaths to 50 in Mali. -

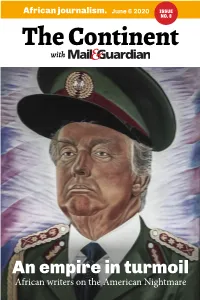

The Continent ISSUE 8

African journalism. June 6 2020 ISSUE NO. 8 The Continent with An empire in turmoil African writers on the American Nightmare The Continent Page 2 ISSUE 8. June 6 2020 Editorial Are we numb? Africans need to tell our own stories. their shoulders and accept systemic This philosophy is the reason The discrimination as a fact of life. Continent exists. As we witness America’s turmoil, But we also need to tell other we should take a long, hard look at people’s stories. That’s why, for this ourselves. At least 18 Kenyan citizens special edition, we have commissioned have been shot dead by police officers so African writers and journalists based far this year. In Nigeria, a human rights in the United States to describe the turmoil the land of the free is currently As we witness America’s experiencing – and to explain why it’s happening. turmoil, we should take a For once, we are the foreign hard look at ourselves correspondents, reporting on unrest and upheaval in a strange, faraway land. body recorded the extrajudicial killing And what a strange land it is. To see of 18 people in just two weeks in April. a nation state founded on the principle Ethiopian security forces were accused of democracy (for some, at least) use last month of burning homes to the violence against peaceful protesters ground, summarily executing civilians is a jarring reminder that America’s and raping women. And in South government does not itself subscribe Africa, with its long history of violent to the democratic values it so loudly reprisals to protect capital, soldiers were advocates abroad.