The Early History of Transylvania University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transfer Times Page1

Transfer Times page1 Fall 2015 Volume 9, Issue 1 TRANSFER TIMES HAT S YOUR ESTINATION W ’ D ? Cypress College Transfer Center, 2nd Floor Student Center www.CypressCollege.edu/services/transfer 9200 Valley View St., Cypress, CA, 90630 (714) 484-7129 [email protected] INSIDE THIS ISSUE Spring Graduation Application Deadline Has Moved Spring Graduation Application 1 Important Dates 1 Transfer Applications Due 2 Admissions and Records has moved the application dead- line for spring graduation to November 30th. This is ap- Workshop Series for Future Law Students 2 proximately two and one half months earlier that it was last Walk-in Application Help 2 year. The reason it has been moved is to give the evaluators Transfer Tuesdays 3 more time to review applications for the Associate Degree Transfer Guarantee to HBCUs 3 for Transfer (ADT). Transfer Center Services 3 Transfer Awareness Week Schedule of This deadline is especially important for students who will complete their ADT in Spring 2016. In order to receive the Activities 4 benefits of the ADT it has to be verified. According to Ka- ren Simpson-Alisca from the California State University Important Dates (CSU) Chancellor's Office, "...there are three levels of verification in the ADT process. The first is the students self- UC Application: reporting on their CSU Mentor application The application website is open from August 1st th that they have already earned or in pro- to November 30 . You can submit our application st gress of completing an AA-T or AS-T de- beginning November 1 . gree. The second is the eVerify process and the third and final verification is receipt CSU Application: The application website opens st of the students final transcripts with the on October 1 . -

Preliminary Fall 2019 Enrollments in Illinois Higher Education

Item #I-1 December 10, 2019 PRELIMINARY FALL 2019 ENROLLMENTS IN ILLINOIS HIGHER EDUCATION Submitted for: Information. Summary: This report summarizes preliminary fall-term 2019 headcount and full-time equivalent (FTE) enrollments at degree-granting colleges and universities in Illinois. The report also summarizes enrollments in remedial/developmental courses during the 2018- 2019 academic year. Fall 2019 preliminary headcount enrollments at degree-granting institutions total 720,215 and preliminary FTE enrollments total 541,187. Brisk Rabbinical College did not respond to the survey and therefore was excluded from the report. Action Requested: None 323 Item #I-1 December 10, 2019 PRELIMINARY FALL 2019 ENROLLMENTS IN ILLINOIS HIGHER EDUCATION This report summarizes preliminary fall-term 2019 headcount and full-time-equivalent (FTE) enrollments at colleges and universities in Illinois. It also includes enrollments in remedial/developmental courses for Academic Year 2018-2019. Fall-term enrollments provide a “snapshot” of Illinois higher education enrollments on the 10th day, or census date, of the fall term. It should be noted that two colleges, Brisk Rabbinical College did not respond to the survey and was therefore excluded from the report. Preliminary fall 2018 enrollments by sector Including enrollments at out-of-state institutions authorized to operate in Illinois, fall 2019 preliminary headcount enrollments at degree-granting institutions total 720,215 (see Table 4 for institutional level data). Fall 2019 FTE enrollments total 541,187. -

Kenyon Collegian Archives

Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange The Kenyon Collegian Archives 10-18-2018 Kenyon Collegian - October 18, 2018 Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.kenyon.edu/collegian Recommended Citation "Kenyon Collegian - October 18, 2018" (2018). The Kenyon Collegian. 2472. https://digital.kenyon.edu/collegian/2472 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives at Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Kenyon Collegian by an authorized administrator of Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ESTABLISHED 1856 October 18, 2018 Vol. CXLVI, No.8 Former SMAs create new group after losing confidentiality DEVON MUSGRAVE-JOHNSON SMA Program. In response, some of changes to the SMA program that SMAs would fall into the category support to peer education,” SPRA EDITOR-IN-CHIEF former SMAs have created a new included the discontinuation of the of mandated reporter, which means wrote in an email to the Collegian. support organization: Sexual Re- 24-hour hotline and the termination that the group could no longer have “While peer education is important, On Oct. 8, Talia Light Rake ’20 spect Peer Alliance.” of their ability to act as a confidential legal confidentiality and that the we recognize that there is a great need sent a statement through student Just a day before the letter was resource for students. Beginning this school could be held liable for infor- for peer support on this campus. We email titled “An Open Letter from released to the public, 16 of the 17 year, SMAs were required to file re- mation relayed to the SMAs. -

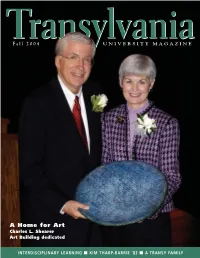

A Home for Art Charles L

TTFall 2004ransylvaniaransylvaniaUNIVERSITY MAGAZINE A Home for Art Charles L. Shearer Art Building dedicated INTERDISCIPLINARY LEARNING ■ KIM THARP-BARRIE ’83 ■ A TRANSY FAMILY THE BINGHAM-YOUNG PROFESSORSHIP ON LIBERTY,LIBERTY, SECURITY,SECURITY, ANDAND JUSTICEJUSTICE Philosophy professor Peter Fosl’s two-year Bingham-Young Professorship offers an engaging and stimulating mix of speakers, panel discussions, seminars, workshops, visiting artists, film screenings, art exhibits, and theatrical events, all aimed at illuminating issues of liberty, security, and justice in today’s world. The program recognizes that these issues have taken on new urgency since the terrorist attacks on the United States of September 11, 2001. More information on the program and upcoming events, many of which are open to the public, may be found at www.transy.edu/pages/lsj/home.htm. Jack Girard “Rale”-collage/mix 2004 TransylvaniaUNIVERSITY MAGAZINE FALL/2004 Features 9 Giving and Receiving Service learning travel course to the Philippines helps students gain new perspectives on the world 12 A Fitting Tribute Transylvania celebrates dedication of the Charles L. Shearer 9 Art Building and the Susan P. Shearer Student Gallery 14 Crossing Academic Borders Transylvania professors and students embrace an integrated, interdisciplinary approach to teaching and learning 18 A Caring Life Kim Tharp-Barrie ’83 has combined a nurturing spirit with leadership skills to become highly successful in healthcare 12 20 A Transy Family Tree Five consecutive generations of the Gamboe/McGuire family have earned Transylvania degrees, beginning in 1896 Around Campus 2 New faculty members 20 4 Transy student finds Hollywood in Kentucky 5 Transy officially in NCAA Division III 6 New residence halls planned Alumni News and Notes 22 Class Notes 25 Alumni Profile: Joe Thomson ’66 27 Alumni Profile: Shelby Spanyer Sheffield ’95 on the cover 29 Marriages, Births, Obituaries President Charles L. -

2020 Orange County Annual Survey

2020 ORANGE COUNTY ANNUAL SURVEY PREPARED BY: FRED SMOLLER MICHAEL A. MOODIAN TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ............................................................................................................2 Introduction .......................................................................................................................3 Data Collection ..................................................................................................................3 Orange County Profile ........................................................................................................3 Attitudes Toward Climate Change ........................................................................................4 Lack of Support For Trump’s Climate Change Stance ..............................................................5 Support For the State’s Climate Change Efforts ......................................................................5 Banning the Internal Combustion Engine ...............................................................................6 Personal Actions to Fight Climate Change .............................................................................6 The Great Park, San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station (SONGS), and Managed Retreat .........7 Party Differences ................................................................................................................7 Age Differences .................................................................................................................8 -

College Name Adrian College Advocate Illinois Masonic Medical

College Name Adrian College Advocate Illinois Masonic Medical Center Albion College Alverno College American Academy of Art Aquinas College Argosy University Ashford University Augustana College Aurora University Ball State University Barry University Beloit College Benedictine University Blackburn College Bradley University Briar Cliff University Butler University Cardinal Stritch University Carleton College Carroll College Carthage College Catholic University of America Central Michigan University Chamberlain Col of Nursing Chicago State University Christian Brothers University Clarke College Coe College Colorado College Colorado State University College of St. Benedict & St. John's University College of St. Catherine Columbia College of Chicago Concorida University Cooking & Hospitality Institute Cornell College Coyne American Institute Creighton University Culver Stockton College DePaul University DePauw University DeVry University Dominican University Drake University Drury University East-West University Eastern Illinois University Eastern Michigan University Edgewood College Elmhurst College Embry Riddle Aeronautical University Eureka College Fairfield University The Fashion Institue of Design & Merchandising Ferris State University Grand Valley State Grinnell College Harrington College of Design Hillsdale College Holy Cross College Illinois College Illinois Institute of Art Illinois Institute of Technology Illinois State University Illinois Wesleyan University Indiana University Indiana U-Purdue U International Academy of Design -

2011 AIKCU Technology Awards

2011 AIKCU Technology Awards ASSOCIATION OF INDEP E N D E N T KENTUCKY COLLEGES AN D BEST NEW CAMPUS BEST STUDENT ONLINE SERVICE APPLICATIONUNIVERSITIES SYSTEM Nominees are: Nominees are: Campbellsville University - CASHNet Portal Integration Berea College - New Student Online Orientation and Transylvania University - MOX Mobil Application Course Registration System Georgetown College - GC Mobile University of the Cumberlands - Roommate Student Housing System Transylvania University - Campus Digital Signage Union College - PWM Open Source Password Self University of the Cumberlands - UC Website Service for LDAP Directories This award is given to the school who has demonstrated the University of the Cumberlands - EDUCAN spirit of digital use by providing the most efficient, effective, University of the Cumberlands - Efficient Asset and creative online services to their students. Management System University of the Cumberlands - Time and MOST SUCCESSFUL Attendance INFRASTRUCTURE PROJECT University of Pikeville - Retension Alert This award is given to the school that has implemented a Nominees are: major new application or has significantly enhanced an existing system that improves operational performance and/or service Brescia University - Securing Campus Network for all or part of its students, faculty, and staff. Access for Improved User Experience Campbellsville University - Virtualization Initiative MOST INNOVATIVE USE OF Centre College - Watchtower TECHNOLOGY FOR INSTRUCTIONAL PURPOSES Transylvania University – PaperCut Print Control University of the Cumberlands - UC Wireless Nominees are: University of the Cumberlands - Network Berea College - BC-OnDemand Infrastructure Expansion Project University of the Cumberlands - iLearn Bypass This award is given to the school that has implemented Exams major changes to its technology infrastructure resulting in improved services and/or cost savings. -

Employee Handbook

EMPLOYEE HANDBOOK December 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................. 1 II. EMPLOYEE CLASSIFICATIONS ................................................................. 1 III. NON-EMPLOYEE CLASSIFICATIONS ....................................................... 1 IV. PERSONNEL ADMINISTRATION ................................................................ 2 V. EMPLOYMENT PROCEDURES………………….….…………………….3 VI. COMPENSATION ............................................................................................ 6 VII. BENEFITS .......................................................................................................... 7 VIII. ALTERNATIVE DISPUTE RESOLUTION ................................................ 16 IX. GENERAL INFORMATION ......................................................................... 17 APPENDIX 1 Policies for On-campus Religious Groups/Ministry Advisors ........... 23 APPENDIX 2 Volunteer Policy ..................................................................................... 25 APPENDIX 3 Background Screening Policy ............................................................... 26 APPENDIX 4 Computer Lab Reservation Policy........................................................ 29 APPENDIX 5 Consensual Relationship Policy ........................................................... 30 APPENDIX 6 Policy Prohibiting Harassment ............................................................. 32 APPENDIX 7 Office, Building, -

Just for Families Student Services

Just For Families Student Services DeAnn Yocum Gaffney, Ed.D. Associate Vice President for Student Affairs and Senior Associate Dean of Students Student Success Many services to support your student’s success Services based on We are here to help! assessment and data. Student Services Overview • Peer and Health Education • Student Health Center • Student Psychological Counseling Services • Disability Services • Public Safety • Parent Programs • Cross-Cultural Center Student Services Video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TRlGnKCg2h4 Student Services Video https://www.youtube.com/embed/Yt8Rpdj206g?rel=0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yt8Rpdj206g&feature=youtu.be PEER and Health Education • Prevention Focused Programs • Education • Awareness • Engagement • Empowering and supporting students • Connect / Resources / Support • Reducing college students’ risky behaviors in relation to alcohol, sex, and consent Dr. Dani Smith [email protected] Director Sexual Assault Crisis Counselor Licensed Therapist 29 years working at Chapman PEER • Proactive Prevention • Education • Encouraging • Responsibility Public Health Perspective Prevention PEER and Health Education Healthy Panther Initiative • A required program for all new first-year and transfer undergraduate students • Designed to empower students with the information and skills necessary for healthy decision-making • Help make positive decisions regarding sex, alcohol/drugs, and personal health • Information regarding sexual misconduct, reporting options, resources, and prevention including -

Fhu-Fhu1 (800) 348-3481

2009-10 Undergraduate Catalog of Freed-Hardeman University Learning, Achieving, Serving “Teaching How to Live and How to Make a Living” Freed-Hardeman University 158 East Main Street Henderson, Tennessee 38340-2399 (731) 989-6000 (800) FHU-FHU1 (800) 348-3481 NON-DISCRIMINATORY POLICY AS TO STUDENTS Freed-Hardeman University admits qualified students of any race, color, national or ethnic origin to all the rights, privileges, programs, and activities generally accorded or made available to students at the school. Freed-Hardeman does not discriminate on the basis of age, handicap, race, color, national or ethnic origin in administration of its educational policies, admissions policies, scholarship and loan programs, and athletic and other school-administered programs. Except for certain exemptions and limitations provided for by law, the university, in compliance with Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, does not discriminate on the basis of sex in admissions, in employment, or in the educational programs and activities which it operates with federal aid. Inquiries concerning the application of Title IX may be referred to Dr. Samuel T. Jones, Freed-Hardeman University, or to the Director of the Office for Civil Rights of the Department of Education, Washington, DC 20202. TABLE OF CONTENTS GENERAL INFORMATION Message from President Joe A. Wiley .................................................................................... 5 Purpose Statement ........................................................................................................... -

2015-16 Tennis Founded in 1842, Ohio Wesleyan Ohio Wesleyan Employs 146 Full- Is a National University with a Major Time Faculty

2015-16 Tennis Founded in 1842, Ohio Wesleyan Ohio Wesleyan employs 146 full- is a national university with a major time faculty. Nearly 100 percent of international presence. Accredited by Ohio Wesleyan in Brief the tenure-track faculty hold a Ph.D. the North Central Association of Col- or equivalent or are completing work leges and Schools, OWU is a member of LOCATION >> Delaware, Ohio 43015 toward the degree. The student-faculty the Great Lakes Colleges Association, a ratio is 11:1. consortium of 13 leading independent FOUNDED >> 1842 Ohio Wesleyan currently enrolls institutions in Indiana, Michigan, and about 1750 students, almost equally ENROLLMENT 1675 Ohio. >> men and women, from nearly every Ohio Wesleyan has been named state and more than 40 countries. The NICKNAME Battling Bishops to the President’s Higher Education >> multicultural enrollment total of ap- Community Service Honor Roll — the COLORS >> Red and Black proximately 16 percent includes U.S. highest federal recognition a school can multicultural students and interna- achieve for service learning and civic PRESIDENT >> Dr. Rock Jones tional students. engagement — for 6 consecutive years. Diversity, creativity, leadership, Ohio Wesleyan confers the Bach- HOME COURTS >> Luttinger Family and service are emphasized through- elor of Arts, Bachelor of Fine Arts, and Tennis Center out the co-curriculum. Students are Bachelor of Music degrees. The Univer- active in nearly 100 clubs and orga- sity also offers combined-degree (3-2) AFFILIATION >> NCAA Division III nizations, as well as departmental programs in engineering, interdisci- student boards, academic honoraries, CONFERENCE North Coast Athletic plinary and applied science, medical >> music and theatre productions, frater- technology, optometry, and physical nities and sororities, and an extensive WEBSITE www.owu.edu therapy. -

Master of Science State & Institutional

Master of Science State & Institutional Representation 2012 - 2020 Alma Maters Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College Drury University Alice Lloyd College East Tennessee State University Allegheny College Eastern Kentucky University Appalachian State University Elon University Arizona State University Emory University Auburn University Emory & Henry College Augustana College Ferris State University Austin Peay State University Ferrum College Bakersfield College Florida A&M University Ball State University Florida Atlantic University Barry University Florida Gulf Coast University Baylor University Florida Institute of Technology Belmont University Florida International University Benedictine University Florida Southern University Bellevue University Florida State University Belmont University Franciscan University of Steubenville Berea College George Mason University Berry College Georgetown College Bowling Green State University Georgetown University Brigham Young University George Washington University Brown University Georgia Gwinnett College California Lutheran University Georgia Institute of Technology California State Polytechnic University-Pomona Gonzaga University California State University Grand Valley State University California State University Bernardino Hanover College California State University Fullerton Houghton College California State University Long Beach Houston Baptist University California State University Los Angeles Howard University Campbellsville University Hunter College Carson-Newman University Illinois Wesleyan