Corneille's Absent Characters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1629 Corneille Pierre Mélite C 1630 Corneille Pierre Clitandre Ou L

1629 Corneille Pierre Mélite C 1630 Corneille Pierre Clitandre ou l'innocence persécutée TC 1632 Corneille Pierre La Veuve C 1632 Corneille Pierre Mélanges poétiques 1633 Corneille Pierre La Galerie du Palais C 1634 Corneille Pierre La Suivante C 1634 Corneille Pierre La Place Royale ou l'Amour extravagant C 1635 Corneille Pierre Médée T 1636 Corneille Pierre L'Illusion comique C 1637 Corneille Pierre Le Cid TC 1637 Corneille et 4 autres La Grande Pastorale 1640 Corneille Pierre Horace T 1642 Corneille Pierre Cinna T 1643 Corneille Pierre Polyeucte T 1643 Corneille Pierre La Mort de Pompée T 1643 Corneille Pierre Le Menteur C 1644 Corneille Pierre La Suite du Menteur C 1645 Corneille Pierre Rodogune T 1645 Corneille Pierre sixains pour Valdor "Le Triomphe de Louis le Juste" 1646 Corneille Pierre Théodore T 1647 Corneille Pierre Héraclius T 1650 Corneille Pierre Andromède T 1650 Corneille Pierre Don Sanche d'Aragon CH 1651 Corneille Pierre Nicomède T 1651 Corneille Pierre trad. de l'"Imitation de Jésus-Christ", 20 ch. 1652 Corneille Pierre Pertharite T 1659 Corneille Pierre Oedipe T 1660 Corneille Pierre La Toison d'or (T à machines) 1662 Corneille Pierre Sertorius T 1663 Corneille Pierre Sophonisbe T 1664 Corneille Pierre Othon T 1666 Corneille Pierre Agésilas T 1667 Corneille Pierre Attila T 1669 Corneille Pierre trad. de l'"Office de la Vierge" 1670 Corneille Pierre Tite et Bérénice T 1671 Corneille + Molière/Quinault Psyché CB 1672 Corneille Pierre Pulchérie T 1674 Corneille Pierre Suréna T 1654 Molière L'Etourdi 1656 Molière Le Dépit -

Felix W. Leakey Collection 19Th and 20Th Centuries

Felix W. Leakey Collection 19th and 20th centuries Biography/ History Felix W. Leakey (1922‐1999). Felix Leakey was born in Singapore in 1922. He held positions at the universities of Sheffield, Glasgow, and Reading, prior to assuming the position of Professor of French Language and Literature and Head of the Department of French at Bedford College, London University in 1973. Felix Leakey’s distinction as a scholar is based on his writings on the French poet Charles Baudelaire (1821‐1867). After completing his Ph.D. thesis on Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du Mal, Leakey received wide praise for his study, Baudelaire and Nature, published in 1969. The originality of Leakey’s contributions to Baudelaire studies consists of his chronological approach to Les Fleurs du Mal and his position that Baudelaire’s aesthetic theories evolved throughout the poet’s life. Leakey published selected poems from Les Fleurs du Mal translated into English verse in 1994 and 1997. While traveling in Ireland, Leakey discovered the original manuscript of Samuel Beckett’s translation of Arthur Rimbaud’s “Le Bateau ivre.” Drunken boat: a translation of Arthur Rimbaud’s poem Le Bateau ivre was published by Whiteknights Press in 1976 with introductions by Leakey and James Knowlson, a renowned Beckett scholar. It was the wish of Felix Leakey that this collection be donated to the W.T. Bandy Center at Vanderbilt University. Professor Leakey died in Northumberland, England in 1999. The donation was made in 2000. For additional information see: Patricia Ward. “The Felix Leakey Collection”. Bulletin Baudelairien, XXXVIII, numéros 1 et 2 (avril‐décembre 2003), 29‐34. -

An Anthropology of Gender and Death in Corneille's Tragedies

AN ANTHROPOLOGY OF GENDER AND DEATH IN CORNEILLE’S TRAGEDIES by MICHELLE LESLIE BROWN (Under the Direction of Francis Assaf) ABSTRACT This study presents an analysis of the relationship between gender and death in Corneille’s tragedies. He uses death to show spectators gender-specific types of behavior to either imitate or reject according to the patriarchal code of ethics. A character who does not conform to his or her gender role as dictated by seventeenth-century society will ultimately be killed, be forced to commit suicide or cause the death of others. Likewise, when murderous tyrants refrain from killing, they are transformed into legitimate rulers. Corneille’s representation of the dominance of masculine values does not vary greatly from that of his contemporaries or his predecessors. However, unlike the other dramatists, he portrays women in much stronger roles than they usually do and generally places much more emphasis on the impact of politics on the decisions that his heroes and heroines must make. He is also innovative in his use of conflict between politics, love, family obligations, personal desires, and even loyalty to Christian duty. Characters must decide how they are to prioritize these values, and their choices should reflect their conformity to their gender role and, for men, their political position, and for females, their marital status. While men and women should both prioritize Christian duty above all else, since only men were in control of politics and the defense of the state, they should value civic duty before filial duty, and both of these before love. Since women have no legal right to political power, they are expected to value domestic interests above political ones. -

Théâtre II : Clitandre

THEATRE II Du même auteur, dans la même collection Le Cid (édition avec dossier). Horace (édition avec dossier). L'Illusion comique (édition avec dossier). La Place royale (édition avec dossier). Théâtre I : Mélite. La Veuve. La Galerie du palais. La Sui- vante. La Place royale. L'Illusion comique. Le Menteur. La Suite du Menteur. Théâtre II : Clitandre. Médée. Le Cid. Horace. Cinna. Polyeucte. La Mort de Pompée. Théâtre III : Rodogune. Héraclius. Nicomède. Œdipe. Tite et Bérénice. Suréna. Trois Discours sur le poème dramatique (édition avec dossier). CORNEILLE THÉÂTRE II CLITANDRE - MÉDÉE - LE CED - HORACE CINNA - POLYEUCTE - LA MORT DE POMPÉE Introduction, chronologie et notes par Jacques Maurens Nouvelle bibliographie par Arnaud Welfringer (2006) GF Flammarion www.centrenationaldulivre.fr Éditions Flammarion, Paris, 1980 ; édition mise à jour en 2006. ISBN : 978-2-0807-1282-0 CHRONOLOGIE 1602 : Pierre Corneille, le père, maître des eaux et forêts épouse à Rouen Marthe Le Pesant, fille d'un avocat. 1606 : Le 6 juin, naissance à Rouen, rue de la Pie, de Pierre Corneille; il aura cinq frères ou sœurs, dont Tho- mas et Marthe, mère de Fontenelle. 1615 : II entre au collège des Jésuites de la ville; prix de vers latins en rhétorique (1620). 1624 : Corneille est licencié en droit; il prête serment d'avocat stagiaire au Parlement de Rouen. 1628 : Son père achète pour lui deux offices d'avocat du roi, au siège des eaux et forêts et à l'amirauté de France. Il conservera ces charges jusqu'en 1650. 1629 : Milite est jouée au Marais pendant la saison théâ- trale 1629-1630, probablement début décembre 1629. -

From the Tragic to the Comic in Corneille

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity Modern Languages and Literatures Faculty Research Modern Languages and Literatures Department 2005 Over the Top: From the Tragic to the Comic in Corneille Nina Ekstein Trinity University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/mll_faculty Part of the Modern Languages Commons Repository Citation Ekstein, N. (2005). Over the top: From the tragic to the comic in Corneille. In F. E. Beasley & K. Wine (Eds.), Intersections: Actes du 35e congrès annuel de la North American Society for Seventeenth-Century French Literature, Dartmouth College, 8-10 mai 2003 (pp. 73-84). Tübingen, Germany: Narr. This Contribution to Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Modern Languages and Literatures Department at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in Modern Languages and Literatures Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Over the Top: From the Tragic to the Comic in Corneille by NINA EKSTEIN (Trinity University) The notions of tragedy and comedy that one can intuit from the theater of Corneille are markedly different from those found in other authors of the period. This is but one aspect of a larger issue concerning Corneille's placement in the hallowed pantheon of literary history. He is one of the major canonical authors and yet he often disconcerts.1 He was one of the principal theorists of drama in the seventeenth century and yet he took a number of stands in direct and lonely opposition to his peers. -

Polyeucte's Gad Marching Boldly and Joyfully Ta Martyrdom, Poly- Eucte

Polyeucte's Gad Marching boldly and joyfully ta martyrdom, Poly- eucte, hero of Pierre Corneille's first Christian tragedy Polyeucte, hardly appears as a humble, gentle f ollower of Jesus Christ. Like his Corne- li an predecessors Don Rodrigue and Horace, this saint suggests, by his aggression and fearless zeal, that he seeks more ta satisfy his pride and amour-propre thraugh extraordinary deeds of cou- rage than ta fulfill a duty. Indeed, he never considers how he might bring Christ 's message of hope and joy ta his own people or even whether his defiance of imperial authority will compromise "cet ordre social • • • dont, de g_ar son sang royal, il devait ~tre le gardien." Launching himself on the heroic quest at the first opportu- ni ty, he espouses the cause of Christianity be- cause Jesus' promise of salvation ta the faithful would accord him the "more permanent expressions or manifestations of his générosité" 2 that he sa desires. As Claude Abraham states, ·~e may strive for heaven but only becaus3 there is a bigger and better glory there ••••" For Polyeucte, mar- tyrdom is simply the best way ta enshrine his own name in everlasting glory, and ta his last breath, he will rejoice in his own triumphs, not God's, as Serge Doubrovsky well notes: "La 'palme' de Polyeucte, ce sont les 'trophées' d'Horace, mais avec une garantie éternelle. En mourant pour son Dieu, Pflyeucte meurt donc exclusivement pour lui- m~me." His eyes fixed on the splendor of.his heavenly triumph, the martyr displays a self- assurance and a self-centeredness in his earthly trial that proves he is neither a staunch dévot who wishes ta igspire his wife and father-in-law by his exemple, nor a jealous husband who hopes ta d~stinguish himself as a hero in his wife's eyes. -

![Ncohv [Read Free Ebook] Théâtre II: Clitandre - Médée - Le Cid - Horace - Cinna - Polyeucte - La Mort De Pompée Online](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6220/ncohv-read-free-ebook-th%C3%A9%C3%A2tre-ii-clitandre-m%C3%A9d%C3%A9e-le-cid-horace-cinna-polyeucte-la-mort-de-pomp%C3%A9e-online-686220.webp)

Ncohv [Read Free Ebook] Théâtre II: Clitandre - Médée - Le Cid - Horace - Cinna - Polyeucte - La Mort De Pompée Online

ncohv [Read free ebook] Théâtre II: Clitandre - Médée - Le Cid - Horace - Cinna - Polyeucte - La Mort de Pompée Online [ncohv.ebook] Théâtre II: Clitandre - Médée - Le Cid - Horace - Cinna - Polyeucte - La Mort de Pompée Pdf Free Par Pierre Corneille ebooks | Download PDF | *ePub | DOC | audiobook Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook Détails sur le produit Rang parmi les ventes : #189826 dans eBooksPublié le: 2016-02-24Sorti le: 2016-02- 24Format: Ebook Kindle | File size: 75.Mb Par Pierre Corneille : Théâtre II: Clitandre - Médée - Le Cid - Horace - Cinna - Polyeucte - La Mort de Pompée before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Théâtre II: Clitandre - Médée - Le Cid - Horace - Cinna - Polyeucte - La Mort de Pompée: Commentaires clientsCommentaires clients les plus utiles8 internautes sur 9 ont trouvé ce commentaire utile. un format qui permet de passer un bon momentPar cocace genre de format compact permet de se faire une bonne session de Corneille sans avoir à chaque pièce séparemment, avec en plus une certaine diversité puisque l'on y retrouve à la fois des tragi-comédies et des tragédies. A recommander aux amateurs de théâtre.2 internautes sur 2 ont trouvé ce commentaire utile. Excellent ouvrage à recommanderPar SkylieUn splendide recueil qui regroupe les plus belles tragi- comédies et tragédies de Corneille. Agréable à lire malgré les 600 pages, c'est l'avantage de la pièce de théâtre qui nécessite une aération. A recommander à tous les amateurs d'ouvrages classiques.2 internautes sur 2 ont trouvé ce commentaire utile. Connaître CORNEILLEPar rebollo michellivre bien présenté et contenant les principales pièces de théâtre ( je recommande pour cela de lire les tomes I et II également) - lecture facile pour découvrir l'essentiel de CORNEILLE à travers le théâtre. -

L'illusion Comique Corneille, Pierre

L'Illusion Comique Corneille, Pierre Publication: 1635 Catégorie(s): Fiction, Théâtre, Comédie Source: http://www.ebooksgratuits.com 1 A Propos Corneille: Pierre Corneille (Rouen, 6 juin 1606 - Paris, 1er octobre 1684) est un auteur dramatique français du xviie siècle. Ses pièces les plus célèbres sont Le Cid, Cinna, Polyeucte et Ho- race. La richesse et la diversité de son œuvre reflètent les va- leurs et les grandes interrogations de son époque. Disponible sur Feedbooks pour Corneille: • Le Cid (1636) • Médée (1635) • La Veuve (1633) • La Place Royale ou L'amoureux extravagant (1634) • La suivante (1634) • Clitandre (1632) • La Galerie du Palais (1633) • Mélite (1629) Note: Ce livre vous est offert par Feedbooks. http://www.feedbooks.com Il est destiné à une utilisation strictement personnelle et ne peut en aucun cas être vendu. 2 Adresse À Mademoiselle M. F. D. R. Mademoiselle, Voici un étrange monstre que je vous dédie. Le premier acte n’est qu’un prologue ; les trois suivants font une comédie im- parfaite, le dernier est une tragédie : et tout cela, cousu en- semble, fait une comédie. Qu’on en nomme l’invention bizarre et extravagante tant qu’on voudra, elle est nouvelle ; et sou- vent la grâce de la nouveauté, parmi nos Français, n’est pas un petit degré de bonté. Son succès ne m’a point fait de honte sur le théâtre, et j’ose dire que la représentation de cette pièce ca- pricieuse ne vous a point déplu, puisque vous m’avez comman- dé de vous en adresser l’épître quand elle irait sous la presse. -

Dossier Péda Polyeucte Mise En Page 1

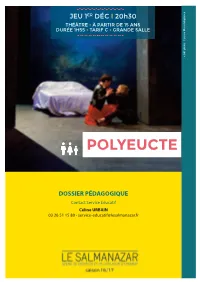

JEU 1ER DÉC I 20h30 THÉÂTRE • À PARTIR DE 15 ANS DURÉE 1H55 • TARIF C • GRANDE SALLE crédit photo : Cosimo Mirco Magliocca POLYEUCTE DOSSIER PÉDAGOGIQUE Contact Service Éducatif Céline URBAIN 03 26 51 15 80 • [email protected] POLYEUCTE Cie Pandora JEU 1ER DÉC I 20h30 THÉÂTRE • À PARTIR DE 15 ANS DURÉE 1H55 • GRANDE SALLE TARIF • de 12,50 à 24,50 € TEXTE Pierre Corneille MISE EN SCÈNE Brigitte Jaques-Wajeman AVEC Clément Bresson, Pascal Bekkar, Aurore Paris, Pauline Bolcatto, Marc Siemiatycki, Timothée Lepeltier, Bertrand Sua- rez-Pazos CONSEILLERS ARTISTIQUES François Regnault, Clément Camar-Mercier ASSISTANT À LA MISE EN SCÈNE Pascal Bekkar SCÉNOGRAPHIE ET COSTUMES Emmanuel Peduzzi LUMIÈRES Nicolas Faucheux CRÉATION SON Stéphanie Gibert RÉGIE GÉNÉRALE ET ACCESSOIRES Franck Lagaroje MAQUILLAGES ET COIFFURES Catherine Saint-Sever CHORÉGRAPHIE Sophie Mayer ASSISTANTE COSTUMES Pascale Robin CONSTRUCTION DÉCOR Ateliers-Jipanco ADMINISTRATION ET PRODUCTION Dorothée Cabrol CHARGÉE DE DIFFUSION Emmanuelle Dandrel Coproduction Théâtre de la Ville - Paris • Compagnie Pandora Avec la participation artistique du Jeune Théâtre National Soutien DRAC Île-de-France - Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication Remerciements à Sixtine Leroy POLYEUCTE Cie Pandora Avec cette pièce de 1641, Corneille met en scène un jeune homme charmant qui, à peine baptisé, cherche le martyr. Héros qui se voue à la mort avec une allé- gresse inquiétante, il décide de s’attaquer, au nom du Dieu unique, aux statues des dieux romains qu’il consi- dère comme des idoles païennes qu’il faut détruire. Entre fidélité à sa jeune épouse et asservissement à Dieu, Polyeucte dans son désir d’absolu, choisit la voie du fanatisme. -

On the Passions of Kings: Tragic Transgressors of the Sovereign's

ON THE PASSIONS OF KINGS: TRAGIC TRANSGRESSORS OF THE SOVEREIGN’S DOUBLE BODY IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY FRENCH THEATRE by POLLY THOMPSON MANGERSON (Under the Direction of Francis B. Assaf) ABSTRACT This dissertation seeks to examine the importance of the concept of sovereignty in seventeenth-century Baroque and Classical theatre through an analysis of six representations of the “passionate king” in the tragedies of Théophile de Viau, Tristan L’Hermite, Pierre Corneille, and Jean Racine. The literary analyses are preceded by critical summaries of four theoretical texts from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in order to establish a politically relevant definition of sovereignty during the French absolutist monarchy. These treatises imply that a king possesses a double body: physical and political. The physical body is mortal, imperfect, and subject to passions, whereas the political body is synonymous with the law and thus cannot die. In order to reign as a true sovereign, an absolute monarch must reject the passions of his physical body and act in accordance with his political body. The theory of the sovereign’s double body provides the foundation for the subsequent literary study of tragic drama, and specifically of king-characters who fail to fulfill their responsibilities as sovereigns by submitting to their human passions. This juxtaposition of political theory with dramatic literature demonstrates how the king-character’s transgressions against his political body contribute to the tragic aspect of the plays, and thereby to the -

Corneille in the Shadow of Molière Dominique Labbé

Corneille in the shadow of Molière Dominique Labbé To cite this version: Dominique Labbé. Corneille in the shadow of Molière. French Department Research Seminar, Apr 2004, Dublin, Ireland. halshs-00291041 HAL Id: halshs-00291041 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00291041 Submitted on 27 Nov 2009 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. University of Dublin Trinity College French Department Research Seminar (6 April 2004) Corneille in the shadow of Molière Dominique Labbé [email protected] http://www.upmf-grenoble.fr/cerat/Recherche/PagesPerso/Labbe (Institut d'Etudes Politiques - BP 48 - F 38040 Grenoble Cedex) Où trouvera-t-on un poète qui ait possédé à la fois tant de grands talents (…) capable néanmoins de s'abaisser, quand il le veut, et de descendre jusqu'aux plus simples naïvetés du comique, où il est encore inimitable. (Racine, Eloge de Corneille) In December 2001, the Journal of Quantitative Linguistics published an article by Cyril Labbé and me (see bibliographical references at the end of this note, before appendixes). This article presented a new method for authorship attribution and gave the example of the main Molière plays which Pierre Corneille probably wrote (lists of these plays in appendix I, II and VI). -

L'illusion Comique De Pierre Corneille Et L'esthétique Du Baroque

UNIVERSITÉ ARISTOTE DE THESSALONIQUE FACULTÉ DES LETTRES DÉPARTEMENT DE LANGUE ET DE LITTÉRATURE FRANÇAISES L'ILLUSION COMIQUE DE PIERRE CORNEILLE ET L'ESTHÉTIQUE DU BAROQUE MÉMOIRE PRÉSENTÉ PAR KYRIAKI DEMIRI SOUS LA DIRECTION DE MADAME LE PROFESSEUR APHRODITE SIVETIDOU THESSALONIQUE 2008 1 UNIVERSITÉ ARISTOTE DE THESSALONIQUE FACULTÉ DES LETTRES DÉPARTEMENT DE LANGUE ET DE LITTÉRATURE FRANÇAISES L’ILLUSION COMIQUE DE PIERRE CORNEILLE ET L’ESTHÉTIQUE DU BAROQUE MÉMOIRE PRÉSENTÉ PAR KYRIAKI DEMIRI SOUS LA DIRECTION DE MADAME LE PROFESSEUR APHRODITE SIVETIDOU THESSALONIQUE 2008 2 TABLE DES MATIÈRES INTRODUCTION .......................................................................... p. 5 CHAPITRE I: L' «étrange monstre» de Corneille: une structure irrégulière et chaotique .......................................................................................... p. 13 CHAPITRE II : Les éléments du baroque 1. L'instabilité ......................................................................... p. 24 2. Le déguisement.................................................................... p. 35 3. L'optimisme ......................................................................... p. 47 4. La dispersion des centres d'intérêt .............................. p. 52 CHAPITRE III: L'esthétique 1. Le thème de l'illusion ........................................................ p. 59 2. La métaphore du théâtre ................................................. p. 70 CONCLUSION ...............................................................................