GREATER LOWELL REGIONAL OPEN SPACE STRATEGY: Analysis and Recommendations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Concord River Diadromous Fish Restoration FEASIBILITY STUDY

Concord River Diadromous Fish Restoration FEASIBILITY STUDY Concord River, Massachusetts Talbot Mills Dam Centennial Falls Dam Middlesex Falls DRAFT REPORT FEBRUARY 2016 Prepared for: In partnership with: Prepared by: This page intentionally left blank. Executive Summary Concord River Diadromous Fish Restoration FEASIBILITY STUDY – DRAFT REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Project Purpose The purpose of this project is to evaluate the feasibility of restoring populations of diadromous fish to the Concord, Sudbury, and Assabet Rivers, collectively known as the SuAsCo Watershed. The primary impediment to fish passage in the Concord River is the Talbot Mills Dam in Billerica, Massachusetts. Prior to reaching the dam, fish must first navigate potential obstacles at the Essex Dam (an active hydro dam with a fish elevator and an eel ladder) on the Merrimack River in Lawrence, Middlesex Falls (a natural bedrock falls and remnants of a breached dam) on the Concord River in Lowell, and Centennial Falls Dam (a hydropower dam with a fish ladder), also on the Concord River in Lowell. Blueback herring Alewife American shad American eel Sea lamprey Species targeted for restoration include both species of river herring (blueback herring and alewife), American shad, American eel, and sea lamprey, all of which are diadromous fish that depend upon passage between marine and freshwater habitats to complete their life cycle. Reasons The impact of diadromous fish species extends for pursuing fish passage restoration in the far beyond the scope of a single restoration Concord River watershed include the importance and historical presence of the project, as they have a broad migratory range target species, the connectivity of and along the Atlantic coast and benefit commercial significant potential habitat within the and recreational fisheries of other species. -

Older Workers Rock! We’Re Not Done Yet!

TM TM Operation A.B.L.E. 174 Portland Street Tel: 617.542.4180 5th Floor E: [email protected] Boston, MA 02114 W: www.operationable.net Older Workers Rock! We’re Not Done Yet! A.B.L.E. SCSEP Office Locations: SCSEP Suffolk County, MA Workforce Central SCSEP Hillsborough County, NH 174 Portland Street, 5th Floor 340 Main Street 228 Maple Street., Ste 300 Boston, MA 02114 Ste.400 Manchester, NH 03103 Phone: 617.542.4180 Worcester, MA 01608 Phone: 603.206.4405 eMail: [email protected] Tel: 508.373.7685 eMail: [email protected] eMail: [email protected] SCSEP Norfolk, Metro West & SCSEP Coos County, NH Worcester Counties, MA Career Center 961 Main Street Quincy SCSEP Office of North Central MA Berlin, NH 03570 1509 Hancock Street, 4th Floor 100 Erdman Way Phone: 603.752.2600 Quincy, MA 02169 Leominster, MA 01453 eMail: [email protected] Phone: 617-302-2731 Tel: 978.534.1481 X261 and 617-302-3597 eMail: [email protected] eMail: [email protected] South Middlesex GETTING WORKERS 45+ BACK TO WORK SINCE 1982 SCSEP Essex & Middlesex Opportunity Council Counties, MA 7 Bishop Street Job Search Workshops | Coaching & Counseling | Training | ABLE Friendly Employers | Resource Room Framingham, MA 01702 280 Merrimack Street Internships | Apprenticeships | Professional Networking | Job Clubs | Job Seeker Events Building B, Ste. 400 Tel: 508.626.7142 Lawerence, MA 01843 eMail: [email protected] Phone: 978.651.3050 eMail: [email protected] 2018 Annual Report September 2018 At Operation A.B.L.E., we work very hard to Operation A.B.L.E. Addresses the Changing Needs keep the quality of our programs up and our costs down. -

Towpaths to Oblivion. the Middlesex Canal and the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, Hass

DOCUMENT RESUME ID 175 745 SO 011 887 AUTHOR Holmes, Cary W. TITLE Towpaths to Oblivion. The Middlesex Canal and the Coming of the Railroad 1792-1853. INSTITUTION Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, Hass.: Northeastern Univ., Boston, Mass. Bureau of Business End Economic Research. PUB DATE 75 VOTE 23p.; For rel., i documents, see SO 011 886 and ED 100 764 AVAILABLE FROM Publication Information Center, Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, Boston, Massachusetts 02106 (free) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Case Studies; Construction (Process); Decision Making; *Economic Factors; *Political Issues; Problem Solving: Rail Transportation: Secondary Education; *Social Factors: *Transportation; *United States History IDENTIFIERS *New England ABSTRACT This narrative history of the MiddleseL Canal frcm 1792-,-3 is designed to be used with "Canal," a role-playing, decis.o -aaking game found in SO 011 886. Economic, social, and politz.al factors related to planning, building, and implementing the canal are considered. The document is presented in three parts. Part I states reasons for studying the Middlesex Canal. It was the first lengthy canal in the United States and served as a model for other canals. In addition, the problems that arose are typical of those that lust be dealt with in relation to aay type of transportation system. Part II describes events leading up to the canal opening in 1903, including legislative giants, court regulations, surveys, the introduction of the magnetic compass, and actual construction with its concomitant employment and technical problems. Part III outlines events and factors affecting the rise and fall of revenues, and concludes with the canal's demise in 1853 following the growth of railroad systems. -

Shawsheen Aqueduct, Looking Northeast, Middlesex

SHAWSHEEN AQUEDUCT, LOOKING NORTHEAST, MIDDLESEX CANAL, WILMINGTON-BILLERICA, MASSACHUSETTS OLD-TIME NEW ENGLAND d ’ Quarter/y magazine Devoted to the cffncient Buildings, Household Furnishings, Domestic A-ts, 5l4anner.s and Customs, and Minor cffntipuities of L?Wqew England Teop/e BULLETIN OFTHE SOCIETYFOR THE PRESERVATIONOF NEW ENGLAND ANTIQUITIES Volume LVIII, No. 4 April-June I 968 Serial No. 212 Comparison of The Blackstone and Middlesex Canals By BRENTON H. DICKSON HREE major canals were com- granting the Blackstone its charter. The pleted in Massachusetts in the idea of a canal connecting Boston with T first twenty-odd years of the the Merrimack River and diverting the nineteenth century : the Middlesex, that great natural resources of New Hamp- went from Boston to Lowell, or more shire away from Newburyport and into correctly, from Charlestown to Middle- Boston met with wholehearted approval sex Village in the outskirts of Lowell; the in the capital city; however, the idea of Blackstone that went from Worcester to the landlocked treasures of Worcester Providence ; and the Hampshire and County making their way to the market Hampden, or Farmington, that went by way of Rhode Island, and seeing Prov- from Northampton to New Haven. To- idence benefit from business that rightly day we will just concern ourselves with belonged to Boston, was unthinkable. the first two of these. When the Blackstone Canal finally got They were both conceived about the its charter in 1823, Bostonians dreaded same time in the early 1790’s. The more than ever the evil effects of such a Middlesex began operating in 1803 but waterway. -

City of Haverhill, Massachusetts Open Space and Recreation Plan

CITY OF HAVERHILL, MASSACHUSETTS OPEN SPACE AND RECREATION PLAN FOR THE MASSACHUSETTS EXECUTIVE OFFICE OF ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENTAL AFFAIRS – DIVISION OF CONSERVATION SERVICES OCTOBER 2008 – OCTOBER 2015 The City of Haverhill Open Space & Recreation Plan Page 1 of 257 October 2008 – October 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS Section I Plan Summary 6 Section II Introduction 7 A. Statement of Purpose 7 B. Planning Process and Public Participation 7 Section III Community Setting 9 A. Regional Context 9 B. History of the Community 9 C. Population Characteristics 13 D. Growth and Development Patterns 18 Section IV Environmental Inventory and Analysis 32 A. Geology, Soils, and Topography 32 B. Landscape Character 33 C. Water Resources 34 D. Vegetation 38 E. Fisheries and Wildlife 38 F. Scenic Resources and Unique Environments 40 G. Environmental Challenges 48 Section V Inventory of Lands of Conservation and Recreation Interest 54 A. Private Parcels B. Public and Nonprofit Parcels Section VI Community Vision 70 A. Description of Process 70 B. Statement of Open Space and Recreation Goals 71 Section VII Analysis of Needs 73 A. Summary of Resource Protection Needs 73 B. Summary of Community’s Needs 80 C. Management Needs, Potential Change of Use 84 Section VIII Goals and Objectives 90 Section IX Seven-Year Action Plan 94 Section X Public Comments 105 Section XI References 114 Appendices 115 The City of Haverhill Open Space & Recreation Plan Page 2 of 257 October 2008 – October 2015 Appendix A. 2008-2015 Open Space and Recreation Plan Mapping, produced by the Merrimack Valley Planning Commission Locus Map Zoning Districts Aggregated Land Use Soils and Geologic Features Water and Wetland Resources Unique Landscape Features Scenic, Historic, and Cultural Resources Lands of Conservation and Recreation Interest 5 Year Action Plan Appendix B. -

2019 Greater Lowell Community Health Needs Assessment

2019 Greater Lowell Community Health Needs Assessment in partnership with 295 Varnum Avenue, Lowell, MA 01854-2193 978-937-6000 • TTY:978-937-6889 • www.lowellgeneral.org 2019 Greater Lowell Community Health Needs Assessment Conducted on behalf of: Lowell General Hospital Greater Lowell Health Alliance Authors: David Turcotte, ScD Kelechi Adejumo, MSc Casey León, MPH Kim-Judy You, BSc University of Massachusetts Lowell September 17, 2019 295 Varnum Avenue, Lowell, MA 01854-2193 978-937-6000 • TTY:978-937-6889 • www.lowellgeneral.org ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to acknowledge and thank the Members of the 2019 Community Health Needs following individuals and organizations for their Assessment Advisory Committee (see Appendix E) assistance with the 2019 Community Health Needs and Greater Lowell Health Alliance, for their advice Assessment and this report: and guidance. Krysta Brugger, UMass Lowell graduate student The Cambodian Mutual Assistance Association for her help with scheduling listening sessions, (CMAA), Center of Hope and Healing, Elder participant recruitment, and project management; Services of Merrimack Valley, Greater Lowell Interfaith Leadership Alliance, Hunger and Hannah Tello, a University of Massachusetts Lowell Homeless Commission, Lowell’s Early Childhood doctoral student who designed the Greater Lowell Council, Lowell Community Health Center, Lowell Community Needs Assessment survey, compiled House, Lowell Housing Authority, Lowell Senior the results, and wrote the summary section for this Center, Non-Profit Alliance of Greater Lowell (NPA), report. UMass Lowell students Mollie McDonah, Portuguese Senior Center, RISE Coalition (Refugee Jared Socolow, Shirley Archambault, and Larissa and Immigrant Support & Engagement), Youth Medeiros, and Lowell High student Andrew Nguyen Violence Prevention Coalition, Upper Merrimack and Innovation Charter School student Joshua Cho Valley Public Health Coalition for hosting for assistance with conducting survey outreach and listening sessions. -

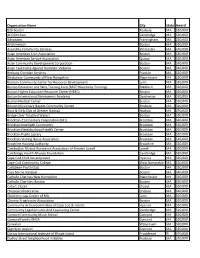

Tab11 Title I Performance Quarterly

TAB 11 FY05 WIA TITLE I PERFORMANCE MEASURE SUMMARY BY WIB AREA Quarterly Report Period Ending 6/30/05 ADULT MEASURES Chart 1: Entered Employment Chart 2: Credential Chart 3: Employment Retention Chart 4: Earnings Gain DISLOCATED WORKER MEASURES Chart 5: Entered Employment Chart 6: Credential Chart 7: Employment Retention Chart 8: Earnings Gain OLDER YOUTH MEASURES Chart 9: Entered Employment Chart 10: Credential Chart 11: Employment Retention Chart 12: Earnings Gain YOUNGER YOUTH MEASURES Chart 13: Skill Attainment Chart 14: Diploma/GED Attainment Chart 15: Employment/Education Retention Data Source: WIA Title I Quarterly Report Data (ETA 9090) Compiled by Performance and Reporting Department, Massachusetts Division of Career Services Report Date: 8/12/2005 COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS WIA TITLE I PERFORMANCE MEASURES: FY05 QUARTERLY PERIOD ENDING 06/30/2005 CHART 1- ADULT ENTERED EMPLOYMENT RATE IN FIRST QUARTER AFTER EXIT [B] [C] [D] [E=B-C-D] [F] [G] [H=F+G] [I=H/E] [J] [K=I/J] Total Medical & Employed at Adjusted Number of Number of Total Number Entered Local Percent of Workforce Number of Other Registration Number of Wage Record Supplemental of Entered Employment Performance Local Goal Investment Area Exiters Exclusions Exiters Matches Employments Employments Rate Level Goal Berkshire 47 4 3 40 28 3 31 78% 74% 105% Boston 196 4 36 156 115 4 119 76% 70% 109% Bristol 58 4 5 49 35 1 36 74% 71% 104% Brockton 59 2 8 49 35 6 41 84% 74% 113% Cape Cod, Vineyard, Nantucket 59 2 10 47 26 7 33 70% 70% 100% Central Mass 80 3 7 70 51 9 60 86% -

Your NAMI State Organization

Your NAMI State Organization State: Massachusetts State Organization: NAMI Massachusetts Address: NAMI Massachusetts 529 Main St Ste 1M17 Boston, MA 02129-1127 Phone: (617) 580-8541 Fax: (617) 580-8673 Email Address: [email protected] Website: http://www.namimass.org President: Mathieu Bermingham Affiliate Name Contact Info NAMI Berkshire County Address: NAMI Berkshire County 333 East St Room 417 Pittsfield, MA 01201-5312 Phone: (413) 443-1666 Email Address: [email protected] Website: http://www.namibc.org Serving: Berkshire County NAMI Bristol County, MA Email Address: [email protected] Website: http://www.namibristolcounty.org NAMI Cambridge/Middlesex Phone: (617) 984-0527 Email Address: [email protected] Website: http://www.nami-cambridgemiddlesex.org Serving: Allston, Arlington, Belmont, Brighton, Brookline, Cambridge, Charlestown, Somerville, Greater Boston NAMI Cape Ann Address: NAMI Cape Ann 43 Gloucester Avenue Gloucester, MA 01930 Phone: (978) 281-1557 Email Address: [email protected] Website: http://www.namicapeann.org Serving: Cape Ann area, MA NAMI Cape Cod Address: NAMI Cape Cod 5 Mark Ln Hyannis, MA 02601-3792 Phone: (508) 778-4277 Email Address: [email protected] Website: http://www.namiCapeCod.org Serving: Cape Cod and The Islands NAMI Central MA Address: NAMI Central MA 309 Belmont St Rm G1B9 Worcester, MA 01604-1059 Phone: (508) 368-3562 Email Address: [email protected] NAMI Central Middlesex Address: NAMI Central Middlesex PO Box 2793 Acton, MA 01720-6793 Phone: (781) 982-3318 -

Ocm85835802-2010-Lowell.Pdf (692.4Kb)

Massachusetts Department of WorkDevelopmentforce Regional LMI Profile Annual Profile for Greater Lowell Workforce Area May 2010 Commonwealth of Massachusetts Executive Office of Labor and Workforce Development MassLMI Labor Market Information Joanne F. Goldstein Table of Contents (Workforce Area) Overview and Highlights Pages 1-4 Labor market and population highlights of the workforce area. Workforce Area Maps Pages 5-7 Map of the 16 workforce areas in Massachusetts, map of individual workforce area, and an alphabetical listing of the cities and towns within each workforce area. Profile of Unemployment Insurance Claimants Page 8 Grid of unemployment claims statewide and by workforce area for March 2010. Demographic data is displayed for race, gender, and Hispanic or Latino status. Also provided is the duration of unemployment, the average weekly wage during the 12 months prior to the filing, age group, and level of educational attainment. Page 9 March 2010 data on continued claimants for unemployment insurance residing in the local workforce area. Demographic data are displayed for race, gender and Hispanic or Latino status of the claimants. Data are also provided for length of the current spell of unemployment, the average weekly wage during the 12 months prior to filing, age group, and level of educational attainment. For comparison purposes statewide statistics are also provided. Page 10 The occupational categories of the continued claimants arranged in accordance with 22 major groups of the Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) system. The accompanying chart compares the occupational distribution of claimants in the local area with the statewide claimants for the ten largest groups. Page 11 The industry distribution of the continued claimants’ former employer grouped into the 2-digit sectors of the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS). -

Tracing the Aqueducts Through Newton

Working to preserve open space in Newton for 45 years! tthhee NNeewwttoonn CCoonnsseerrvvaattoorrss NNEEWWSSLLEETTTTEERR Spring Issue www.newtonconservators.org April / May 2006 EXPLORING NEWTON’S HISTORIC AQUEDUCTS They have been with us for well over a century, but the Cochituate and Sudbury Aqueducts remain a PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE curiosity to most of us. Where do they come from and where do they go? What are they used for? Why Preserving Echo Bridge are they important to us now? In this issue, we will try to fill in some of the blanks regarding these As part of our planning for the aqueducts in fascinating structures threading their way through our Newton, we cannot omit Echo Bridge. This distinctive city, sometimes in clear view and then disappearing viaduct carried water for decades across the Charles into hillsides and under homes. River in Newton Upper Falls from the Sudbury River to To answer the first question, we trace the two Boston. It is important to keep this granite and brick aqueducts from their entry across the Charles River structure intact and accessible for the visual beauty it from Wellesley in the west to their terminus in the provides. From a distance, the graceful arches cross the east near the Chestnut Hill Reservoir (see article on river framed by hemlocks and other trees. From the page 3). Along the way these linear strands of open walkway at the top of the bridge, you scan the beauty of space connect a series of parks and playgrounds. Hemlock Gorge from the old mill buildings and falls th The aqueducts were constructed in the 19 upriver to the meandering water and the Route 9 century to carry water from reservoirs in the overpass downstream. -

EM28819-16-60-A-25 Mod 0 Grant Agreement

GRANT AWARD - Grant No: EM-28819-16-60-A-25 Mod No.: 0 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF LABOR NOTICE OF EMPLOYMENT AND TRAINING AWARD (NOA) ADMINISTRATION (DOL/ETA) Under the authority of the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA), Title I, Section 170, National Dislocated Worker Grant, this grant or agreement is entered into between the above named Grantor Agency and the following named Awardee, for a project entitled - MA-Regular~Greater Lowell Multi NDWG. Name & Address of Awardee: Federal Award Id. No. (FAIN): EM-28819-16-60-A-25 Massachusetts - EXECUTIVE OFFICE OF LABOR AND CFDA #: 17.277- Workforce Investment Act (WIA) WORKFORCE DEVELOPMENT National Emergency Grants 19 STANIFORD STREET Amount:$1,040,264.00 1ST FLOOR EIN: 046002284 BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS 02114 DUNS #: 947581567 Accounting Code: 1630-2016-0501741616BD201601740003165DW093A0000AOWI00AOWI00-A90200-410023-ETA- DEFAULT TASK- The Period of Performance shall be from January 01, 2016 thru September 30, 2017. Total Government's Financial Obligation is $1,040,264.00 (unless other wise amended). Payments will be made under the Payments Management System, and can be automatically drawn down by the awardee on an as needed basis covering a forty-eight (48) hour period. In performing its responsibilities under this grant agreement, the awardee hereby certifies and assures that it will fully comply with all applicable Statute(s), and the following regulations and cost principles, including any subsequent amendments: Uniform Administrative Requirements, Cost Principles, and Audit Requirements: 2 CFR Part 200; Uniform Administrative Requirements, Cost Principles, and Audit Requirements; Final Rule 2 CFR Part 2900; DOL Exceptions to 2 CFR Part 200; Other Requirements (Included within this NOA): Condition(s) of Award (if applicable) Federal Award Terms, including attachments Contact Information The Federal Project Officer (FPO) assigned to this grant is Kathleen Mclaughlin. -

Organization Name

Organization Name City State Award 826 Boston Roxbury MA $10,000 ACCION East Cambridge MA $10,000 Advocates Framingham MA $10,000 ArtsEmerson Boston MA $10,000 Ascentria Community Services Worcester MA $10,000 Asian American Civic Association Boston MA $10,000 Asian American Service Association Quincy MA $10,000 Asian Community Development Corporation Boston MA $10,000 Asian Task Force Against Domestic Violence Boston MA $10,000 Bethany Christian Services Franklin MA $10,000 Bhutanese Community of New Hampshire Manchester NH $10,000 Bosnian Community Center for Resource Development Lynn MA $10,000 Boston Education and Skills Training Corp (BEST Hospitality Training) Medford MA $10,000 Boston Higher Education Resource Center (HERC) Boston MA $10,000 Boston International Newcomers Academy Dorchester MA $10,000 Boston Medical Center Boston MA $10,000 Boston Missionary Baptist Community Center Roxbury MA $10,000 Boys & Girls Club of Greater Nashua Nashua NH $10,000 Bridge Over Troubled Waters Boston MA $10,000 Brockton 21st Century Corporation (B21) Brockton MA $10,000 Brockton Interfaith Community Brockton MA $10,000 Brockton Neighborhood Health Center Brockton MA $10,000 Brockton Public Library Brockton MA $10,000 Brockton Visiting Nurse Association Brockton MA $10,000 Brookline Housing Authority Brookline MA $10,000 Cambodian Mutual Assistance Association of Greater Lowell Lowell MA $10,000 Cambridge Health Alliance Foundation Cambridge MA $10,000 Cape Cod Child Development Hyannis MA $10,000 Cape Cod Community College West Barnstable MA