WHISTLEBLOWING in ACTION in the EU INSTITUTIONS Prepared

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

Tuesday Volume 540 21 February 2012 No. 266 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Tuesday 21 February 2012 £5·00 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2012 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Parliamentary Click-Use Licence, available online through The National Archives website at www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/information-management/our-services/parliamentary-licence-information.htm Enquiries to The National Archives, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 4DU; e-mail: [email protected] 723 21 FEBRUARY 2012 724 reviewed for potential savings following the Treasury-led House of Commons pilot exercise that I described, which was undertaken at Queen’s hospital, Romford. Tuesday 21 February 2012 Oliver Colvile: Given that the PFI process has been proven to have flaws in delivering value for money for The House met at half-past Two o’clock taxpayers, what effect does my right hon. Friend feel that that will have on new commissioning boards? PRAYERS Mr Lansley: My hon. Friend will know from the very good work being done by the developing clinical [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] commissioning groups in Plymouth that they have a responsibility to use their budgets to deliver the best BUSINESS BEFORE QUESTIONS care for the population they serve. It is not their responsibility to manage the finances of their hospitals LONDON LOCAL AUTHORITIES AND TRANSPORT FOR or other providers; that is the responsibility of the LONDON (NO.2)BILL [LORDS] (BY ORDER) strategic health authorities for NHS trusts and of Monitor for foundation trusts. In the future, it will be made very TRANSPORT FOR LONDON (SUPPLEMENTAL TOLL clear that the providers of health care services will be PROVISIONS)BILL [LORDS] (BY ORDER) regulated for their sustainability, viability and continuity Second Readings opposed and deferred until Tuesday of services but will not pass those costs on to the 28 February (Standing Order No. -

European Parliament Elections 2014

European Parliament Elections 2014 Updated 12 March 2014 Overview of Candidates in the United Kingdom Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 2 2.0 CANDIDATE SELECTION PROCESS ............................................................................................. 2 3.0 EUROPEAN ELECTIONS: VOTING METHOD IN THE UK ................................................................ 3 4.0 PRELIMINARY OVERVIEW OF CANDIDATES BY UK CONSTITUENCY ............................................ 3 5.0 ANNEX: LIST OF SITTING UK MEMBERS OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT ................................ 16 6.0 ABOUT US ............................................................................................................................. 17 All images used in this briefing are © Barryob / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY-SA-3.0 / GFDL © DeHavilland EU Ltd 2014. All rights reserved. 1 | 18 European Parliament Elections 2014 1.0 Introduction This briefing is part of DeHavilland EU’s Foresight Report series on the 2014 European elections and provides a preliminary overview of the candidates standing in the UK for election to the European Parliament in 2014. In the United Kingdom, the election for the country’s 73 Members of the European Parliament will be held on Thursday 22 May 2014. The elections come at a crucial junction for UK-EU relations, and are likely to have far-reaching consequences for the UK’s relationship with the rest of Europe: a surge in support for the UK Independence Party (UKIP) could lead to a Britain that is increasingly dis-engaged from the EU policy-making process. In parallel, the current UK Government is also conducting a review of the EU’s powers and Prime Minister David Cameron has repeatedly pushed for a ‘repatriation’ of powers from the European to the national level. These long-term political developments aside, the elections will also have more direct and tangible consequences. -

Conservative Party

Royaume-Uni 73 élus Parti pour Démocrates libéraux Une indépendance de Parti conservateur ECR Parti travailliste PSE l’indépendance du Les Verts PVE ALDE l'Europe NI Royaume-Uni MELD 1. Vicky Ford MEP 1. Richard Howitt MEP 1. Andrew Duff MEP 1. Patrick O’Flynn 1. Paul Wiffen 1. Rupert Read 2. Geoffrey Van Orden 2. Alex Mayer 2. Josephine Hayes 2. Stuart Agnew MEP 2. Karl Davies 2. Mark Ereira-Guyer MEP 3. Sandy Martin 3. Belinda Brooks-Gordon 3. Tim Aker 3. Raymond Spalding 3. Jill Mills 3. David Campbell 4. Bhavna Joshi 4. Stephen Robinson 4. Michael Heaver 4. Edmond Rosenthal 4. Ash Haynes East of England Bannerman MEP 5. Paul Bishop 5. Michael Green 5. Andrew Smith 5. Rupert Smith 5. Marc Scheimann 4. John Flack 6. Naseem Ayub 6. Linda Jack 6. Mick McGough 6. Dennis Wiffen 6. Robert Lindsay 5. Tom Hunt 7. Chris Ostrowski 7. Hugh Annand 7. Andy Monk 7. Betty Wiffen 7. Fiona Radic 6. Margaret Simons 7. Jonathan Collett 1. Ashley Fox MEP 1. Clare Moody 1. Sir Graham Watson 1. William Dartmouth 1. David Smith 1. Molly Scott Cato 2. Julie Girling MEP 2. Glyn Ford MEP MEP 2. Helen Webster 2. Emily McIvor 3. James Cracknell 3. Ann Reeder 2. Kay Barnard 2. Julia Reid 3. Mike Camp 3. Ricky Knight 4. Georgina Butler 4. Hadleigh Roberts 3. Brian Mathew 3. Gawain Towler 4. Andrew Edwards 4. Audaye Elesady South West 5. Sophia Swire 5. Jude Robinson 4. Andrew Wigley 4. Tony McIntyre 5. Phil Dunn 5. -

European Parliament Elections 2009 RESEARCH PAPER 09/53 17 June 2009

European Parliament Elections 2009 RESEARCH PAPER 09/53 17 June 2009 Elections to the European Parliament were held across the 27 states of the European Union between 4 and 7 June 2009. The UK elections were held concurrently with the county council elections in England on 4 June. The UK now has 72 MEPs, down from 78 at the last election, distributed between 12 regions. The Conservatives won 25 seats, both UKIP and Labour 13 and the Liberal Democrats 11. The Green Party held their two seats, while the BNP won their first two seats in the European parliament. Labour lost five seats compared with the comparative pre-election position. The Conservatives won the popular vote overall, and every region in Great Britain except the North East, where Labour won, and Scotland, where the SNP won. UKIP won more votes than Labour. UK turnout was 34.5%. Across Europe, centre-right parties, whether in power or opposition, tended to perform better than those on the centre-left. The exact political balance of the new Parliament depends on the formation of Groups. The UK was not alone in seeing gains for far-right and nationalistic parties. Turnout across the EU was 43%. It was particularly low in some of the newer Member States. Part 1 of this paper presents the full results of the UK elections, including regional analysis and local-level data. Part 2 presents summary results of the results across the EU, together with country-level summaries based on data from official national sources. Adam Mellows-Facer Richard Cracknell Sean Lightbown Recent Research -

Women in Power A-Z of Female Members of the European Parliament

Women in Power A-Z of Female Members of the European Parliament A Alfano, Sonia Andersdotter, Amelia Anderson, Martina Andreasen, Marta Andrés Barea, Josefa Andrikiené, Laima Liucija Angelilli, Roberta Antonescu, Elena Oana Auconie, Sophie Auken, Margrete Ayala Sender, Inés Ayuso, Pilar B Badía i Cutchet, Maria Balzani, Francesca Băsescu, Elena Bastos, Regina Bauer, Edit Bearder, Catherine Benarab-Attou, Malika Bélier, Sandrine Berès, Pervenche Berra, Nora Bilbao Barandica, Izaskun Bizzotto, Mara Blinkevičiūtė, Vilija Borsellino, Rita Bowles, Sharon Bozkurt, Emine Brantner, Franziska Katharina Brepoels, Frieda Brzobohatá, Zuzana C Carvalho, Maria da Graça Castex, Françoise Češková, Andrea Childers, Nessa Cliveti, Minodora Collin-Langen, Birgit Comi, Lara Corazza Bildt, Anna Maria Correa Zamora, Maria Auxiliadora Costello, Emer Cornelissen, Marije Costa, Silvia Creţu, Corina Cronberg, Tarja D Dăncilă, Vasilica Viorica Dati, Rachida De Brún, Bairbre De Keyser, Véronique De Lange, Esther Del Castillo Vera, Pilar Delli, Karima Delvaux, Anne De Sarnez, Marielle De Veyrac, Christine Dodds, Diane Durant, Isabelle E Ernst, Cornelia Essayah, Sari Estaràs Ferragut, Rosa Estrela, Edite Evans, Jill F Fajon, Tanja Ferreira, Elisa Figueiredo, Ilda Flašíková Beňová, Monika Flautre, Hélène Ford, Vicky Foster, Jacqueline Fraga Estévez, Carmen G Gabriel, Mariya Gál, Kinga Gáll-Pelcz, Ildikó Gallo, Marielle García-Hierro Caraballo, Dolores García Pérez, Iratxe Gardiazábal Rubial, Eider Gardini, Elisabetta Gebhardt, Evelyne Geringer de Oedenberg, Lidia Joanna -

Financial Management and Fraud in the European Union: Perceptions, Facts and Proposals

HOUSE OF LORDS European Union Committee 50th Report of Session 2005–06 Financial Management and Fraud in the European Union: Perceptions, Facts and Proposals Volume II: Evidence Ordered to be printed 7 November 2006 and published 13 November 2006 Published by the Authority of the House of Lords London : The Stationery Office Limited £price HL Paper 270-II CONTENTS Page Oral Evidence Mr Ivan Lewis MP, Economic Secretary to HM Treasury, Mr Chris Austin, Head of EU Finance and Mr Chris Butler, Head of Assurance, HM Treasury Written evidence 1 Oral evidence, 2 May 2006 4 Supplementary written evidence 15 Letter from Ed Balls MP, Economic Secretary 17 Mr Hubert Weber, President, Mr Vitor Manuel da Silva Caldeira, Member, Mr David Bostock, Member and Mr Josef Bonnici, Member, European Court of Auditors Oral evidence, 16 May 2006 18 Commissioner Kallas, Commissioner for Administrative Affairs, Audit and Anti-Fraud, Mr Kristian Schmidt, Mr Brian Gray and Mr Reijo Kemppinen, European Commission Written evidence 34 Oral evidence, 6 June 2006 38 Supplementary written evidence 45 Sir John Bourn, Comptroller and Auditor General, Ms Caroline Mawhood and Mr Frank Grogan, National Audit Office Written evidence 45 Oral evidence, 6 June 2006 48 Supplementary written evidence 53 Mr Ashley Mote MEP, European Parliament and Mr Christopher Arkell Written evidence 56 Oral evidence, 13 June 2006 61 Mr Terry Wynn MEP, European Parliament Written evidence 70 Oral evidence, 27 June 2006 73 Mr Brian Gray, Accounting Officer, European Commission Written evidence -

Act Before July 5 to Ban Illegal Timber in the UK and Europe

“It is very important that people in other countries help us to preserve our forests by not using illegal wood. I would like voters in Europe to support this ban on importing illegal wood as it will serve our children – they will inherit the results.” Alberto Granados, Olancho, Honduras Act before July 5 to ban illegal timber in the UK and Europe: www.progressio.org.ukAct before July 5 to ban illegal timber from the UK and Europe Thank you for downloading this PROactive campaign action sheet and for supporting Progressio’s illegal logging action. The vote is on July 5, so there’s not much time to get our voices heard. While there is some hope in the European Parliament for the legislation which has been agreed, we still need to make sure our politicians know that there is public support to ban illegal timber. This is our chance and it is vital that we take it. Included on this sheet is everything you’ll need to tell our politicians we don’t want illegal timber in the UK or Europe: A short text for your church bulletin or to email around A general intercession for Sunday Mass on June 27 and July 4 A suggested text to write a letter to MEPs A list of MEPs by region A poster to print and display in a prominent place is included on the front of this pack Short text: You can use the following text in your church bulletin or personal emails to spread the word: Illegal logging is a disaster for poor communities. -

Women Candidates and Party Practice in the UK: Evidence from the 2009 European Elections

Women candidates and party practice in the UK: evidence from the 2009 European Elections Abstract Existing comparative research suggests that women candidates have better opportunities for electoral success when standing in (i) second order elections and (ii) PR elections - the 2009 European Elections provide an example of both criteria. This paper examines the 2009 results to build upon earlier work on the 1999 and 2004 elections by considering (i) regional patterns across parties, with reference to any strategies to improve women‟s representation (ii) incumbency effects (iii) effects of changes in seat shares across parties. --------- EXISTING research on previous European elections demonstrated that the willingness of political parties to place women in the top places on party lists varied, equity in terms of candidate numbers did not result in equity in representation if women languished at the lower end of party lists. Furthermore, virtually all parties failed to take advantage of their own retiring MEPs to promote women1. In the 2005 European Election it was clear that both the Labour Party and the Liberal Democrats had taken the most „positive action‟, whilst Conservative equality rhetoric had failed to materialise into notable female candidate selection, and the electoral success of UKIP served as a hindrance to female representation in general. The number of UK MEPs in total declined from 78 (three in Northern Ireland) in 2004 to 72 in 2009 (69 in Great Britain). Women constitute just under 32% of MEPs, compared to 24% as a result of the 2004 elections. The mainstream political parties in the UK foster different attitudes towards equality promotion and equality guarantees. -

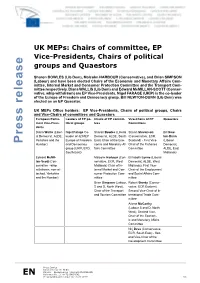

P Re S S Re Le A

UK MEPs: Chairs of committee, EP Vice-Presidents, Chairs of political groups and Quaestors Sharon BOWLES (Lib Dem), Malcolm HARBOUR (Conservative), and Brian SIMPSON (Labour) and have been elected Chairs of the Economic and Monetary Affairs Com- mittee, Internal Market and Consumer Protection Committee and the Transport Com- mittee respectively. Diana WALLIS (Lib Dem) and Edward McMILLAN-SCOTT (Conser- vative, whip withdrawn) are EP Vice-Presidents. Nigel FARAGE (UKIP) is the co-leader of the Europe of Freedom and Democracy group. Bill NEWTON-DUNN (Lib Dem) was elected as an EP Quaestor. UK MEPs Office holders: EP Vice-Presidents, Chairs of political groups, Chairs and Vice-Chairs of committees and Quaestors European Parlia- Leaders of EP po- Chairs of EP commit- Vice-Chairs of EP Quaestors ment Vice-Presi- litical groups tees Committees dents Diana Wallis (Liber- Nigel Farage Co- Sharon Bowles (Liberal Struan Stevenson Bill New- al Democrat, ALDE, leader of 32 MEP Democrat, ALDE, South (Conservative, ECR, ton-Dunn Yorkshire and the Europe of Freedom East) Chair of the Eco- Scotland) - First Vice- (Liberal Press release Humber) and Democracy nomic and Monetary Af- Chair of the Fisheries Democrat, group (UKIP, EFD, fairs Committee Committee ALDE, East South East) Midlands) Edward McMil- Malcolm Harbour (Con- Elizabeth Lynne (Liberal lan-Scott (Con- servative, ECR, West Democrat, ALDE, West servative - whip Midlands) Chair of In- Midlands), First Vice- withdrawn, non-at- ternal Market and Con- Chair of the Employment tached, Yorkshire sumer -

The European Union in the Interests of the United States?

Heritage Special Report SR-10 Published by The Heritage Foundation September 12, 2006 Is the European Union in the Interests of the United States? A CONFERENCE HELD JUNE 28, 2005 GLOBAL BRITAIN Is the European Union in the Interests of the United States? June 28, 2005 Contributors Listed in order of appearance: John Hilboldt Director, Lectures and Seminars, The Heritage Foundation Becky Norton Dunlop Vice-President for External Relations, The Heritage Foundation Senator Gordon Smith United States Senator for Oregon Lord Pearson of Rannoch House of Lords Christopher Booker Journalist and Editor The Rt. Hon. David Heathcoat-Amory MP House of Commons Daniel Hannan, MEP Member of the European Parliament Stephen C. Meyer, Ph.D. Senior Fellow, Discovery Institute Yossef Bodansky Former Director, Congressional Task Force against Terrorism and Unconventional Warfare John C. Hulsman, Ph.D. Research Fellow, The Heritage Foundation Ruth Lea Director, Centre for Policy Studies Diana Furchtgott-Roth Senior Fellow, Hudson Institute Ian Milne Director, Global Britain Mark Ryland Vice President, Discovery Institute Marek Jan Chodakiewicz Research Professor of History, Institute of World Politics Kenneth R. Weinstein, Ph.D. Chief Executive Officer, Hudson Institute Judge Robert H. Bork Distinguished Fellow, Hudson Institute Kim R. Holmes, Ph.D. Vice President, Davis Institute for International Studies, The Heritage Foundation Edwin Meese III Chairman, Center for Legal and Judicial Studies, The Heritage Foundation Questions from Audience Listed in order of appearance: Paul Rubig Member of the European Parliament Ana Gomes Member of the European Parliament Sarah Ludford Member of the European Parliament Michael Cashman Member of the European Parliament Tom Ford United States Department of Defense Bill McFadden Unknown Helle Dale Heritage Foundation © 2006 by The Heritage Foundation 214 Massachusetts Avenue, NE Washington, DC 20002–4999 (202) 546-4400 • heritage.org Contents Welcome and Keynote Address . -

Ranking European Parliamentarians on Climate Action

Ranking European Parliamentarians on Climate Action EXECUTIVE SUMMARY CONTENTS With the European elections approaching, CAN The scores were based on the votes of all MEPs on Austria 2 Europe wanted to provide people with some these ten issues. For each vote, MEPs were either Belgium 3 background information on how Members of the given a point for voting positively (i.e. either ‘for’ Bulgaria 4 European Parliament (MEPs) and political parties or ‘against’, depending on if the text furthered or Cyprus 5 represented in the European Parliament – both hindered the development of climate and energy Czech Republic 6 national and Europe-wide – have supported or re- policies) or no points for any of the other voting Denmark 7 jected climate and energy policy development in behaviours (i.e. ‘against’, ‘abstain’, ‘absent’, ‘didn’t Estonia 8 the last five years. With this information in hand, vote’). Overall scores were assigned to each MEP Finland 9 European citizens now have the opportunity to act by averaging out their points. The same was done France 10 on their desire for increased climate action in the for the European Parliament’s political groups and Germany 12 upcoming election by voting for MEPs who sup- all national political parties represented at the Greece 14 ported stronger climate policies and are running European Parliament, based on the points of their Hungary 15 for re-election or by casting their votes for the respective MEPs. Finally, scores were grouped into Ireland 16 most supportive parties. CAN Europe’s European four bands that we named for ease of use: very Italy 17 Parliament scorecards provide a ranking of both good (75-100%), good (50-74%), bad (25-49%) Latvia 19 political parties and individual MEPs based on ten and very bad (0-24%). -

1 Interpreting Toxic Masculinity in Political Parties

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repository@Nottingham Interpreting Toxic Masculinity in Political Parties: A Framework for Analysis Oliver Daddow and Isabelle Hertner Abstract The term ‘toxic masculinity’ was coined in the 1990s by sociologists and psychologists. It has since been appropriated by scholars and commentators interested in gendered behaviours and outcomes in politics. However, despite the attention belatedly being paid to masculinities as part of that research, our appreciation of, specifically, toxic masculinity’s part in shaping political practices remains underdeveloped. This article proposes a move in this direction by designing a conceptual framework for exploring toxic masculinity inside political parties. We adapt findings from the original toxic masculinity literature to generate a series of indicators of toxic masculinity spanning the policy and discursive aspects of party political action. We then test the framework using a paired comparison of two parties of the populist right where we might expect to see relatively high levels of toxic masculinity: the Alternative for Germany and the UK Independence Party. Our empirical findings give us confidence that drawing on the concept of toxic masculinity can provide us with novel insights into the interplay between masculinity and political party cultures. We also hope that it will inspire a significant body of new research into toxic masculinity in political parties from across the party spectrum as well as globally. Keywords toxic masculinity; gender; AfD; Ukip; Nigel Farage 1 Interpreting Toxic Masculinity in Political Parties: A Framework for Analysis 1. Introduction In politics as in society, toxic masculinity – known in Mandarin as ‘straight male cancer’ (Kesvani, 2018) – has become an important focus for public discussion around, as well as the theoretical and applied research into, gender-based violence, misogyny and the mistreatment of women in public life.