Season 2013-2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The University of Chicago Objects of Veneration

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO OBJECTS OF VENERATION: MUSIC AND MATERIALITY IN THE COMPOSER-CULTS OF GERMANY AND AUSTRIA, 1870-1930 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC BY ABIGAIL FINE CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2017 © Copyright Abigail Fine 2017 All rights reserved ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES.................................................................. v LIST OF FIGURES.......................................................................................... vi LIST OF TABLES............................................................................................ ix ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS............................................................................. x ABSTRACT....................................................................................................... xiii INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................ 1 CHAPTER 1: Beethoven’s Death and the Physiognomy of Late Style Introduction..................................................................................................... 41 Part I: Material Reception Beethoven’s (Death) Mask............................................................................. 50 The Cult of the Face........................................................................................ 67 Part II: Musical Reception Musical Physiognomies............................................................................... -

Revisiting Zero Hour 1945

REVISITING ZERO-HOUR 1945 THE EMERGENCE OF POSTWAR GERMAN CULTURE edited by STEPHEN BROCKMANN FRANK TROMMLER VOLUME 1 American Institute for Contemporary German Studies The Johns Hopkins University REVISITING ZERO-HOUR 1945 THE EMERGENCE OF POSTWAR GERMAN CULTURE edited by STEPHEN BROCKMANN FRANK TROMMLER HUMANITIES PROGRAM REPORT VOLUME 1 The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies. ©1996 by the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies ISBN 0-941441-15-1 This Humanities Program Volume is made possible by the Harry & Helen Gray Humanities Program. Additional copies are available for $5.00 to cover postage and handling from the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies, Suite 420, 1400 16th Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036-2217. Telephone 202/332-9312, Fax 202/265- 9531, E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.aicgs.org ii F O R E W O R D Since its inception, AICGS has incorporated the study of German literature and culture as a part of its mandate to help provide a comprehensive understanding of contemporary Germany. The nature of Germany’s past and present requires nothing less than an interdisciplinary approach to the analysis of German society and culture. Within its research and public affairs programs, the analysis of Germany’s intellectual and cultural traditions and debates has always been central to the Institute’s work. At the time the Berlin Wall was about to fall, the Institute was awarded a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to help create an endowment for its humanities programs. -

Hitler's Germania: Propaganda Writ in Stone

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2017 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2017 Hitler's Germania: Propaganda Writ in Stone Aaron Mumford Boehlert Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2017 Part of the Architectural History and Criticism Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Boehlert, Aaron Mumford, "Hitler's Germania: Propaganda Writ in Stone" (2017). Senior Projects Spring 2017. 136. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2017/136 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hitler’s Germania: Propaganda Writ in Stone Senior Project submitted to the Division of Arts of Bard College By Aaron Boehlert Annandale-on-Hudson, NY 2017 A. Boehlert 2 Acknowledgments This project would not have been possible without the infinite patience, support, and guidance of my advisor, Olga Touloumi, truly a force to be reckoned with in the best possible way. We’ve had laughs, fights, and some of the most incredible moments of collaboration, and I can’t imagine having spent this year working with anyone else. -

Oscar Straus Beiträge Zur Annäherung an Einen Zu Unrecht Vergessenen

Fedora Wesseler, Stefan Schmidl (Hg.), Oscar Straus Beiträge zur Annäherung an einen zu Unrecht Vergessenen Amsterdam 2017 © 2017 die Autorinnen und Autoren Diese Publikation ist unter der DOI-Nummer 10.13140/RG.2.2.29695.00168 verzeichnet Inhalt Vorwort Fedora Wesseler (Paris), Stefan Schmidl (Wien) ......................................................................5 Avant-propos Fedora Wesseler (Paris), Stefan Schmidl (Wien) ......................................................................7 Wien-Berlin-Paris-Hollywood-Bad Ischl Urbane Kontexte 1900-1950 Susana Zapke (Wien) ................................................................................................................ 9 Von den Nibelungen bis zu Cleopatra Oscar Straus – ein deutscher Offenbach? Peter P. Pachl (Berlin) ............................................................................................................. 13 Oscar Straus, das „Überbrettl“ und Arnold Schönberg Margareta Saary (Wien) .......................................................................................................... 27 Burlesk, ideologiekritisch, destruktiv Die lustigen Nibelungen von Oscar Straus und Fritz Oliven (Rideamus) Erich Wolfgang Partsch† (Wien) ............................................................................................ 48 Oscar Straus – Walzerträume Fritz Schweiger (Salzburg) ..................................................................................................... 54 „Vm. bei Oscar Straus. Er spielte mir den tapferen Cassian vor; -

THE INCIDENTAL MUSIC of BEETHOVEN THESIS Presented To

Z 2 THE INCIDENTAL MUSIC OF BEETHOVEN THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By Theodore J. Albrecht, B. M. E. Denton, Texas May, 1969 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS. .................. iv Chapter I. INTRODUCTION............... ............. II. EGMONT.................... ......... 0 0 05 Historical Background Egmont: Synopsis Egmont: the Music III. KONIG STEPHAN, DIE RUINEN VON ATHEN, DIE WEIHE DES HAUSES................. .......... 39 Historical Background K*niq Stephan: Synopsis K'nig Stephan: the Music Die Ruinen von Athen: Synopsis Die Ruinen von Athen: the Music Die Weihe des Hauses: the Play and the Music IV. THE LATER PLAYS......................-.-...121 Tarpe.ja: Historical Background Tarpeja: the Music Die gute Nachricht: Historical Background Die gute Nachricht: the Music Leonore Prohaska: Historical Background Leonore Prohaska: the Music Die Ehrenpforten: Historical Background Die Ehrenpforten: the Music Wilhelm Tell: Historical Background Wilhelm Tell: the Music V. CONCLUSION,...................... .......... 143 BIBLIOGRAPHY.....................................-..145 iii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Egmont, Overture, bars 28-32 . , . 17 2. Egmont, Overture, bars 82-85 . , . 17 3. Overture, bars 295-298 , . , . 18 4. Number 1, bars 1-6 . 19 5. Elgmpnt, Number 1, bars 16-18 . 19 Eqm 20 6. EEqgmont, gmont, Number 1, bars 30-37 . Egmont, 7. Number 1, bars 87-91 . 20 Egmont,Eqm 8. Number 2, bars 1-4 . 21 Egmon t, 9. Number 2, bars 9-12. 22 Egmont,, 10. Number 2, bars 27-29 . 22 23 11. Eqmont, Number 2, bar 32 . Egmont, 12. Number 2, bars 71-75 . 23 Egmont,, 13. -

Ceriani Rowan University Email: [email protected]

Nineteenth-Century Music Review, 14 (2017), pp 211–242. © Cambridge University Press, 2016 doi:10.1017/S1479409816000082 First published online 8 September 2016 Romantic Nostalgia and Wagnerismo During the Age of Verismo: The Case of Alberto Franchetti* Davide Ceriani Rowan University Email: [email protected] The world premiere of Pietro Mascagni’s Cavalleria rusticana on 17 May 1890 immediately became a central event in Italy’s recent operatic history. As contemporary music critic and composer, Francesco D’Arcais, wrote: Maybe for the first time, at least in quite a while, learned people, the audience and the press shared the same opinion on an opera. [Composers] called upon to choose the works to be staged, among those presented for the Sonzogno [opera] competition, immediately picked Mascagni’s Cavalleria rusticana as one of the best; the audience awarded this composer triumphal honours, and the press 1 unanimously praised it to the heavens. D’Arcais acknowledged Mascagni’smeritsbut,inthesamearticle,alsourgedcaution in too enthusiastically festooning the work with critical laurels: the dangers of excessive adulation had already become alarmingly apparent in numerous ill-starred precedents. In the two decades prior to its premiere, several other Italian composers similarly attained outstanding critical and popular success with a single work, but were later unable to emulate their earlier achievements. Among these composers were Filippo Marchetti (Ruy Blas, 1869), Stefano Gobatti (IGoti, 1873), Arrigo Boito (with the revised version of Mefistofele, 1875), Amilcare Ponchielli (La Gioconda, 1876) and Giovanni Bottesini (Ero e Leandro, 1879). Once again, and more than a decade after Bottesini’s one-hit wonder, D’Arcais found himself wondering whether in Mascagni ‘We [Italians] have finally [found] … the legitimate successor to [our] great composers, the person 2 who will perpetuate our musical glory?’ This hoary nationalist interrogative returned in 1890 like an old-fashioned curse. -

Teacher Resource Guide

TEACHER RESOURCE GUIDE Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre School Instructional Performances | March, April 2018 | Teacher Resource Guide Choreography by Jerome Robbins The instructional performances have been made possible by the generosity of the Jerome Robbins Foundation and a donor who wishes to remain anonymous. PBT gratefully acknowledges the following organizations for their commitment to our education programming: Allegheny Regional Asset District Henry C. Frick Educational Fund of The Buhl Anne L. and George H. Clapp Charitable Foundation Trust BNY Mellon Foundation Highmark Foundation Claude Worthington Benedum Foundation Peoples Natural Gas Eat ‘n Park Hospitality Group Pennsylvania Council on the Arts Edith L. Trees Charitable Trust Pennsylvania Department of Community ESB Bank and Economic Development Giant Eagle Foundation PNC Bank Grow up Great The Grable Foundation PPG Industries, Inc. Hefren-Tillotson, Inc. Richard King Mellon Foundation James M. The Heinz Endowments and Lucy K. Schoonmaker 2 CONTENTS 4 The Choreographer—Jerome Robbins Fast Facts 5 The Composer— Leonard Bernstein 6 Robbins’ Style of Movement 7 A look into the instructional performance: Classical Ballet—Swan Lake excerpts Neo-classical Ballet—The Symphony 8 Robbins’ Ballet—West Side Story Suite 9 Exploring West Side Story: Lesson Prompts Connections to Romeo and Juliet Entry Pointes Characters and Story Elements 11 Communication and Technology 12 Group Dynamics 13 Conflict, Strategies and Resolutions 15 Pedestrian Movement and Choreography Observing and Developing Movement 16 Social Dances 17 Creating an Aesthetic 18 Musical Theater/Movie/Ballet PBT celebrates the 100th birthday of Jerome Robbins with its May 2018 production of In the Night, Fancy Free and West Side Story Suite. -

Waldeckische Bibliographie“ Im Juni 1998 Gedruckt Wurde (Zu Hochgrebe S

WALDECKISCHE BIBLIOGRAPHIE Bearbeitet von HEINRICH HOCHGREBE 1998 Für die Präsentation im Internet eingerichtet von Dr. Jürgen Römer, 2010. Für die Benutzung ist unbedingt die Vorbemerkung zur Internetpräsentation auf S. 3 zu beachten! 1 EINLEITUNG: Eine Gesamtübersicht über das Schrifttum zu Waldeck und Pyrmont fehlt bisher. Über jährliche Übersichten der veröffentlichten Beiträge verfügen der Waldeckische Landeskalender und die hei- matkundliche Beilage zur WLZ, "Mein Waldeck". Zu den in den Geschichtsblättern für Waldeck u. Pyrmont veröffentlichten Beiträgen sind Übersichten von HERWIG (Gbll Waldeck 28, 1930, S. 118), BAUM (Gbll Waldeck 50, 1958, S. 154) und HOCHGREBE (Gbll Waldeck 76, 1988, S. 137) veröffentlicht worden. NEBELSIECK brachte ein Literaturver-zeichnis zur waldeckischen Kir- chengeschichte (Gbll Waldeck 38, 1938, S. 191). Bei Auswahl der Titel wurden die Grenzgebiete Westfalen, Hessen, Itter, Frankenberg und Fritzlar ebenso berücksichtigt wie die frühen geschichtlichen Beziehungen zu den Bistümern Köln, Mainz, Paderborn sowie der Landgrafschaft Hessen-Kassel. Es war mir wohl bewußt, daß es schwierig ist, hier die richtige Grenze zu finden. Es werden auch Titel von waldeckischen Autoren angezeigt, die keinen Bezug auf Waldeck haben. Die Vornamen der Autoren sind ausgeschrieben, soweit diese sicher feststellbar waren, was jedoch bei älteren Veröffentlichungen nicht immer möglich war. Berücksichtigung fanden Titel aus periodisch erscheinenden Organen, wichtige Artikel aus der Ta- gespresse und selbständige Veröffentlichungen in Buch- oder Broschürenform. Für die Bearbeitung der Lokalgeschichte sind hier zahlreiche Quellen aufgezeigt. Bei Überschneidung, bzw. wenn keine klare Scheidung möglich war, sind die Titel u. U. mehrfach, d. h. unter verschiedenen Sachgebieten aufgeführt. Anmerkungen in [ ] sind vom Bearbeiter einge- fügt worden. Verständlicherweise kann eine solche Zusammenstellung keinen Anspruch auf Vollständigkeit er- heben, sie hätte aber auch außerhalb meiner Möglichkeiten gelegen, was besonders für das ältere Schrifttum zutrifft. -

Program Notes by Dr

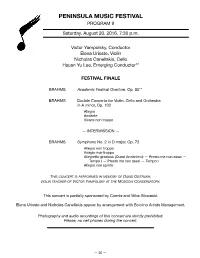

PENINSULA MUSIC FESTIVAL PROGRAM 9 Saturday, August 20, 2016, 7:30 p.m. Victor Yampolsky, Conductor Elena Urioste, Violin Nicholas Canellakis, Cello Hsuan Yu Lee, Emerging Conductor** FESTIVAL FINALE BRAHMS Academic Festival Overture, Op. 80** BRAHMS Double Concerto for Violin, Cello and Orchestra in A minor, Op. 102 Allegro Andante Vivace non troppo — INTERMISSION — BRAHMS Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 73 Allegro non troppo Adagio non troppo Allegretto grazioso (Quasi Andantino) — Presto ma non assai — Tempo I — Presto ma non assai — Tempo I Allegro con spirito THIS CONCERT IS PERFORMED IN MEMORY OF DAVID OISTRAKH, VIOLIN TEACHER OF VICTOR YAMPOLSKY AT THE MOSCOW CONSERVATORY. This concert is partially sponsored by Connie and Mike Glowacki. Elena Urioste and Nicholas Canellakis appear by arrangement with Sciolino Artists Management. Photography and audio recordings of this concert are strictly prohibited. Please, no cell phones during the concert. — 30 — PROGRAM NOTES BY DR. RICHARD E. RODDA Double Concerto for Violin, Cello and Orchestra in A Program 9 minor, Op. 102 JOHANNES BRAHMS (1833-1897) Composed in 1887. Premiered on October 18, 1887 in Cologne, with Joseph Academic Festival Overture, Op. 80 Joachim and Robert Hausmann as soloists and the com- poser conducting. Composed in 1880. Premiered on January 4, 1881 in Breslau, conducted by Johannes Brahms first met the violinist Joseph the composer. Joachim in 1853. They became close friends and musi- cal allies — the Violin Concerto was not only written Artis musicae severioris in Germania nunc princeps for Joachim in 1878 but also benefited from his careful — “Now the leader in Germany of music of the more advice in many matters of string technique. -

Beethoven's Political Music, the Handelian Sublime, and the Aesthetics of Prostration Author(S): Nicholas Mathew Source: 19Th-Century Music, Vol

Beethoven's Political Music, the Handelian Sublime, and the Aesthetics of Prostration Author(s): Nicholas Mathew Source: 19th-Century Music, Vol. 33, No. 2 (Fall 2009), pp. 110-150 Published by: University of California Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/ncm.2009.33.2.110 . Accessed: 26/08/2013 09:38 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of California Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to 19th- Century Music. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 146.232.93.77 on Mon, 26 Aug 2013 09:38:49 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 19TH CENTURY MUSIC Beethoven’s Political Music, the Handelian Sublime, and the Aesthetics of Prostration NICHOLAS MATHEW Viennese Handel and the Power of Music Handel’s music even as he lay dying: music historians have long cherished the image of Johann Reinhold Schultz, reporting on a dinner Beethoven on his deathbed, leafing through all in 1823 at which Beethoven had been present, forty volumes of Handel’s works, sent as a gift recorded that Beethoven had declared Handel from London. -

German Influences Choirs, Repertoires, Nationalities

CHAPTER 1 German Influences Choirs, Repertoires, Nationalities Joep Leerssen The Choir’s Message, the Choir as Medium The German League of Choral Societies held its seventh festival in Breslau in 1906–07. The official programme gazette opened with a poem by the cel- ebrated figure-head of cultural nationalism, Felix Dahn, distinguished profes- sor at the local university, authoritative legal historian, former volunteer in the Franco-Prussian War, author of many a patriotic poem, and famous for his best-selling series of historical novels set at various periods of German and Germanic history. In English translation, the poem runs like this: To the German people God has given / Music of richest sonority In order that rest and struggle, death and life / may be glorified to us in song. So sing on, then, German youth / Of all things which can swell your heart! Of the persistence of true love / Of true friendship, gold and ore; Of the sacred shivers of pious awe / Of the sheen of spring and the joy of the forest Of Wanderlust, roving from land to land / And of that darling son of sunshine —Do not neglect that!—the golden wine. / Yes, sing of all things high and lovely, But above all cherish one specific song / Which should resound inspiring and roaring: The song of the German heroic spirit! / The song of manly duty and honour, Of faithfulness uncowed by fear / Which jubilantly hurls itself onto the foes’ spears And in death wrests victory! / Only he who is willing to die as well as live © Joep Leerssen, 2015 | doi 10.1163/9789004300859_003 This is an open access chapter distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0Joep license. -

Audition Repertoire, Please Contact the Music Department at 812.941.2655 Or by E-Mail at AUDITION REQUIREMENTS for VARIOUS DEGREE CONCENTRATIONS

1 AUDITION GUIDE AND SUGGESTED REPERTOIRE 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS AUDITION REQUIREMENTS AND GUIDE . 3 SUGGESTED REPERTOIRE Piano/Keyboard . 5 STRINGS Violin . 6 Viola . 7 Cello . 8 String Bass . 10 WOODWINDS Flute . 12 Oboe . 13 Bassoon . 14 Clarinet . 15 Alto Saxophone . 16 Tenor Saxophone . 17 BRASS Trumpet/Cornet . 18 Horn . 19 Trombone . 20 Euphonium/Baritone . 21 Tuba/Sousaphone . 21 PERCUSSION Drum Set . 23 Xylophone-Marimba-Vibraphone . 23 Snare Drum . 24 Timpani . 26 Multiple Percussion . 26 Multi-Tenor . 27 VOICE Female Voice . 28 Male Voice . 30 Guitar . 33 2 3 The repertoire lists which follow should be used as a guide when choosing audition selections. There are no required selections. However, the following lists illustrate Students wishing to pursue the Instrumental or Vocal Performancethe genres, styles, degrees and difficulty are strongly levels encouraged of music that to adhereis typically closely expected to the of repertoire a student suggestionspursuing a music in this degree. list. Students pursuing the Sound Engineering, Music Business and Music Composition degrees may select repertoire that is slightly less demanding, but should select compositions that are similar to the selections on this list. If you have [email protected] questions about. this list or whether or not a specific piece is acceptable audition repertoire, please contact the Music Department at 812.941.2655 or by e-mail at AUDITION REQUIREMENTS FOR VARIOUS DEGREE CONCENTRATIONS All students applying for admission to the Music Department must complete a performance audition regardless of the student’s intended degree concentration. However, the performance standards and appropriaterequirements audition do vary repertoire.depending on which concentration the student intends to pursue.