January 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pdf: 660 Kb / 236

As filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on June 23, 2017 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 20-F (Mark One) ‘ REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OR (g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR È ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended: March 31, 2017 OR ‘ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR ‘ SHELL COMPANY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Commission file number: 001-14948 TOYOTA JIDOSHA KABUSHIKI KAISHA (Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in its Charter) TOYOTA MOTOR CORPORATION (Translation of Registrant’s Name into English) Japan (Jurisdiction of Incorporation or Organization) 1 Toyota-cho, Toyota City Aichi Prefecture 471-8571 Japan +81 565 28-2121 (Address of Principal Executive Offices) Nobukazu Takano Telephone number: +81 565 28-2121 Facsimile number: +81 565 23-5800 Address: 1 Toyota-cho, Toyota City, Aichi Prefecture 471-8571, Japan (Name, telephone, e-mail and/or facsimile number and address of registrant’s contact person) Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of Each Class: Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered: American Depositary Shares* The New York Stock Exchange Common Stock** * American Depositary Receipts evidence American Depositary Shares, each American Depositary Share representing two shares of the registrant’s Common Stock. ** No par value. Not for trading, but only in connection with the registration of American Depositary Shares, pursuant to the requirements of the U.S. -

UNITED STATES SECURITIES and EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C

As filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on June 25, 2012 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 20-F (Mark One) ‘ REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OR (g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR È ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended: March 31, 2012 OR ‘ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR ‘ SHELL COMPANY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Commission file number: 001-14948 TOYOTA JIDOSHA KABUSHIKI KAISHA (Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in its Charter) TOYOTA MOTOR CORPORATION (Translation of Registrant’s Name into English) Japan (Jurisdiction of Incorporation or Organization) 1 Toyota-cho, Toyota City Aichi Prefecture 471-8571 Japan +81 565 28-2121 (Address of Principal Executive Offices) Kenichiro Makino Telephone number: +81 565 28-2121 Facsimile number: +81 565 23-5800 Address: 1 Toyota-cho, Toyota City, Aichi Prefecture 471-8571, Japan (Name, telephone, e-mail and/or facsimile number and address of registrant’s contact person) Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of Each Class: Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered: American Depositary Shares* The New York Stock Exchange Common Stock** * American Depositary Receipts evidence American Depositary Shares, each American Depositary Share representing two shares of the registrant’s Common Stock. ** No par value. Not for trading, but only in connection with the registration of American Depositary Shares, pursuant to the requirements of the U.S. -

Toyota in the World 2011

"Toyota in the World 2011" is intended to provide an overview of Toyota, including a look at its latest activities relating to R&D (Research & Development), manufacturing, sales and exports from January to December 2010. It is hoped that this handbook will be useful to those seeking to gain a better understanding of Toyota's corporate activities. Research & Development Production, Sales and Exports Domestic and Overseas R&D Sites Overseas Production Companies North America/ Latin America: Market/Toyota Sales and Production Technological Development Europe/Africa: Market/Toyota Sales and Production Asia: Market/Toyota Sales and Production History of Technological Development (from 1990) Oceania & Middle East: Market/Toyota Sales and Production Operations in Japan Vehicle Production, Sales and Exports by Region Overseas Model Lineup by Country & Region Toyota Group & Supplier Organizations Japanese Production and Dealer Sites Chronology Number of Vehicles Produced in Japan by Model Product Lineup U.S.A. JAPAN Toyota Motor Engineering and Manufacturing North Head Office Toyota Technical Center America, Inc. Establishment 1954 Establishment 1977 Activities: Product planning, design, Locations: Michigan, prototype development, vehicle California, evaluation Arizona, Washington D.C. Activities: Product planning, Vehicle Engineering & Evaluation Basic Research Shibetsu Proving Ground Establishment 1984 Activities: Vehicle testing and evaluation at high speed and under cold Calty Design Research, Inc. conditions Establishment 1973 Locations: California, Michigan Activities: Exterior, Interior and Color Design Higashi-Fuji Technical Center Establishment 1966 Activities: New technology research for vehicles and engines Toyota Central Research & Development Laboratories, Inc. Establishment 1960 Activities: Fundamental research for the Toyota Group Europe Asia Pacific Toyota Motor Europe NV/SA Toyota Motor Asia Pacific Engineering and Manfacturing Co., Ltd. -

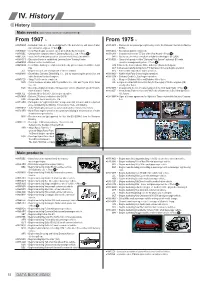

IV. History History

IV. History History Main events (Overseas events are marked with ) From 1907 ~ From 1975 ~ ●1907 MAR • Hatsudoki Seizo Co., Ltd. is established for the manufacture and sales of inter- ●1975 APR • Delivers 24 ten-passenger sightseeing cars to the Okinawa International Marine nal combustion engines. < Photo 1 > EXPO. ●1939 MAY • Ikeda Plant begins operation. (present Head (Ikeda) 1st district) ●1976 DEC • Knockdown plant is completed. ●1951 DEC • Changes the company name to Daihatsu Motor Co., Ltd. < Photo 2 > ●1978 JAN • Charade receives the '77 Car of the Year Award. < Photo 6 > ●1961 JUN • Ikeda 2nd Plant begins operation. (present Head (Ikeda) 2nd district) MAR • Serves as a technical consultant on hybrid technology to GE (USA). ●1963 OCT • Education Center is established. (present Sales Training Center) ●1979 FEB • Starts trial operation of the "Daihatsu Pleat System" automatic EV rental ●1964 MAR • Medical center is established. operation management system. < Photo 7 > ●1965 MAR • Head Office building is completed in Ikeda city. (present main Head Office build- JUN Opens the Representative Office in Europe (Brussels, Belgium). ing) OCT Overseas manufacturing plant (PT. Daihatsu Indonesia) begins operation. JUL • Begins research and development of electric vehicles. DEC • Kobe Center export base starts operation. ●1966 MAY • Establishes Daihatsu Diesel Mfg. Co., Ltd. by separating the production and ●1980 NOV • Nishinomiya Parts Center begins operation. sales functions for diesel engines. ●1981 JUN • Daihatsu Credit Co., Ltd. begins operation. ●1967 FEB • Shiga Test Course is completed. JUL • Merger of Daihatsu Motor and Daihatsu Motor Sales. NOV • Forms business alliance with Toyota Motor Co., Ltd. and Toyota Motor Sales JUL Signs a contract with Inocenti in Italy for the supply of 1000cc engines (CB) Co., Ltd. -

Annual Report 2009 Toyota Tsusho Corporation

Toyota Tsusho Corporation Annual Report 2009 Report Annual Corporation Tsusho Toyota Annual Report 2009 Toyota Tsusho Corporation es nging Tim Seeking New Value in Challe The Toyota Tsusho Group’s long-term vision is to generate balanced earnings from automotive and non-automotive fields by 2015. Guided by this vision, we are working Toyota Tsusho to reinforce and organically fuse four unique business platforms—Resources and the Environment, Processing and Manufacturing Businesses, Logistics, and Product and at a Glance Market Development—to provide value-added functions and services that are matched to customer needs, offer support solutions addressing issues faced by customers and to generate new value. Machinery & Electronics Division Automotive Division Consumer Products, Services & Materials Division Business Strategies for the Automotive Field 2015 50 01 Annual Report 2009 One of our key competitive advantages lies in our global processing and logistics functions in the automotive field, which are grounded on the keywords of “real places, real things, reality,” along with our overseas automobile sales network. In the fields of produce & foodstuffs, energy & chemicals and electronics, other major business assets of ours include the extensive networks we have cultivated and developed worldwide, and our expertise in conducting large-scale business projects that span many years. Metals Division Energy & Chemicals Division Produce & Foodstuffs Division ld otive Fie Non-Autom Business Strategies for the Automotive Field 50 02 Toyota Tsusho -

Company Profile

Company Profile Find out detailed information regarding Toyota's key personnel and facilities, business activities and corporate entities as well as its sales and production growth around the globe. You can also discover more about the various non-automotive pursuits of Toyota and the museums and plant tours which are open to the public. Overview This section lists basic facts about Toyota in addition to the latest activities relating to latest business results. Find out more Executives Here you will find a list of all of Toyota's top management from the chairman and president down to the managing officers. Find out more Figures See more about the global sales and production figures by region. Find out more Toyota Group A list of companies making up the Toyota Group. Facilities View Toyota's design and R&D bases and production sites all around the globe, as well as the many museums of great knowledge. Find out more Non-automotive Business In addition to automobile production, Toyota is also involved in housing, financial services, e-TOYOTA, Marine, biotechnology and afforestation Toyota From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search For other uses, see Toyota (disambiguation). Toyota Motor Corporation Toyota Jidosha Kabushiki-gaisha トヨタ自動車株式会社 Type Public TYO: 7203 Traded as LSE: TYT NYSE: TM Automotive Industry Robotics Financial services Founded August 28, 1937 Founder(s) Kiichiro Toyoda Headquarters Toyota, Aichi, Japan Area served Worldwide Fujio Cho (Chairman) Key people Akio Toyoda (President and CEO) Automobiles Products Financial Services Production output 7,308,039 units (FY2011)[1] Revenue ¥18.583 trillion (2012)[1] [1] Operating income ¥355.62 billion (2012) [1] Profit ¥283.55 billion (2012) [1] Total assets ¥30.650 trillion (2012) [1] Total equity ¥10.550 trillion (2012) Employees 324,747 (2012)[2] Parent Toyota Group Lexus Divisions Scion 522 (Toyota Group) Toyota India Hino Motors, Ltd. -

Annual Report 2014

Annual Report Year ended March 31, 2014 Aiming to Achieve Sustainable Growth and to Bring Smiles ANNUAL REPORT 2014 Print Search Contents Page 2 Overview of Consolidated Performance Management and President’s Message Special Feature Review of Operations Financial Section Investor Information Four Business Units Highlights Corporate Information Prev Next 3 President’s Message 5 Overview of Four Business Units 9 Special Feature Aiming to Achieve Lexus International Toyota’s DNA Will Endure for the Next 100 Years 5 Sustainable Growth Lexus International: Becoming a Truly Global Luxury Brand 10 Toyota in 10 Years and 100 Years and to Bring Smiles Toyota No. 1 6 Our DNA is Creating Ever-Better Cars Improving Our Earnings Structure and Offering Advanced Technologies in Developed Markets 16 Toyota No. 2 Enriching Lives and Building Tomorrow’s Toyota through Innovation 7 19 Supporting Toyota in Future Growth Markets 8 Unit Center 24 Message from the Executive Vice Developing and Commercializing Major Components with Best-in-World Competitiveness President Responsible for Accounting 26 Consolidated Performance Highlights 34 Management and Corporate Information 44 Financial Section 64 Consolidated Statements of Comprehensive Income 34 R&D and Intellectual Property 44 Selected Financial Summary (U.S. GAAP) 65 Consolidated Statements of Shareholders’ Equity 29 Review of Operations 36 Corporate Philosophy 46 Consolidated Segment Information 66 Consolidated Statements of Cash Flows Corporate Governance Consolidated Quarterly Financial Summary Automotive -

Business Report for the 93Rd Fiscal Period

Bridgestone Corporation Business Report for the 93rd Fiscal Period Note: This English translation of the Business Report for the 93rd Fiscal Period is for English readers' convenience only. If there are any differences between this translation and the Japanese original, the Japanese original supersedes this translation. [Index] P.2 Message to Our Shareholders P.4 Business Report P.44 Consolidated Balance Sheet P.46 Consolidated Statements of Income P.47 Consolidated Statements of Changes in Net Assets P.48 Notes for Consolidated Financial Statements P.58 Consolidated Statements of Cash Flows P.60 Non-consolidated Balance Sheet P.62 Non-consolidated Statements of Income P.63 Non-consolidated Statements of Changes in Net Assets P.64 Notes for Non-consolidated Financial Statements P.70 Independent Auditors‘ Report P.74 Board of Corporate Auditors Meeting Audit Report P.77 Topics P.80 New Products and Technologies P.81 Shareholders‘ Notes 1 Message to Our Shareholders Net Sales: ¥3,024.3 billion Operating Income: ¥191.3 billion Ordinary Income: ¥179.3 billion Net Income: ¥102.9 billion First, I would like to convey my thanks to all of our shareholders for your support of the Bridgestone Group. In this message, I will provide an overview of the Bridgestone Group‘s results during its 93rd fiscal year (from January 1, 2011, to December 31, 2011). During this fiscal year, the Group‘s operating environment continued to be plagued by high material prices and the persistence of the strong yen. Domestically, there was some recovery from the impacts of the Great East Japan Earthquake, which occurred on March 11, 2011, but the harsh economic climate this disaster created lingered throughout the year. -

3L7 Japanese Automobile Lobbying in Brussels

3L7 Japanese Automobile Lobbying in Brussels - The Role of the Japanese Motor Car Industry in EU Policy Networks Sabine Spell Scottish Centre for Japanese Studies University of Stirling Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Stirling December 2000 To my parents and Christian without whom I could not achieve my dreams To my parents Errata Xiii (6) North Atlantic Treaty Organisation Xiii (11 + 73) Organisation Industrielle des Constructeurs 10 (11) provided an excellent opportunity 28 (4) define 41 (21) and proposed that new 49 (12) the Sociétd 50 (10) to Japan 55 (10) proposal and in what way 60 (11) With regard to 68 (21) supports.. .provides (13) into its own hands 79 (11) subsidiaries, a fact which 166 (7) Constructeurs des 167 (20) hit their lowest of the decade 185 229 (4) their corporate (7) influence 232 rare occasion on which 258 (FN15) (6) interpretations and discussions 263 (23) produced in the EC 264 283 (1) is obvious (3) At this stage, one can only speculate 289 290 (15) but to support 293 (17) In this way 296 (2) beneath the surface 311 (19) not to offend them directly 312 (7) a reduction in the cost 317 (2) the cost 338 (24) who are not invited Contents Abstract vi Conventions vii Acknowledgements viii Glossary xi Introduction 1 Chapter I: The Policy Network Concept 23 1.1: Introduction of the Policy Network Concept 24 1.2: The Marsh and Rhodes Typology of Policy Networks 29 1.3: Policy Networks in the European Union 32 1.4: Recent Criticisms of Marsh's and Rhodes's 36 'Traditional' Concept Chapter II: Lobbying the European Union 44 11.1: Lobbying 'en générale'. -

Honda Motor Company's Cvcc Engine

. HE 1 8.5 .A3 4 )RT NOS. DOT-TSC-NHTSA-80-3 no HS-805268 DOT- TSC- NHTSA- 8(1-3 HONDA MOTOR COMPANY'S CVCC ENGINE 0 / William J. Abernathy Larry Ronan LEXINGTON TECHNOLOGY ASSOCIATES 10 Wingate Road Lexington MA 02173 JL'LY 1980 FINAL REPORT DOCUMENT IS available TO THE PUBLIC THROUGH THE NATIONAL TECHNICAL INFORMATION S E I I I R V C E . SP R NG F E L D, VIRGINIA 22161 Prepared for U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION NATIONAL HIGHWAY TRAFFIC SAFETY ADMINISTRATION Office of Resear CP and Development Washington DC 20590 . NOTICE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Govern- ment assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof NOTICE ' The United States Government does not endorse pro- ducts or manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers' names appear herein solely because they are con- sidered essential to the object of this report. — Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. HS-805268 4. Ti tie ond Subti tie 5. Report Date July 1980 HONDA MOTOR COMPANY'S CVCC ENGINE 6. Performing Orgonizafion Code 8. Performing Orgonization Report No. 7. Author'' s) DOT-TSC-NHTSA-80-3 william J. Abernathy and Larry Ronan 9. Performing Organization Nome and Address 10. J(fc»,rk UmfJdo. (TPAISl HS028/R0404 Lexington Technology Associates* 11. Contract or Grant No. 10 Wingate Road DOT-TSC-1355 Lexington MA 02173 13. Type of Report and Period Covered 12. Sponsoring Agency Nome and Address U.S. -

Fact Book 2016

SUBARU CORPORATION Fact Book 2016 Corporate Communications Dept. SUBARU Fact book 2016 54 Corporate Information Contents ※Click title to jump to the details. Corporate Information 1 Profile 3 Aerospace Company 2 Mid-term Management Vision 4 1 Aircraft Production 31 3 Board Directors / Executive Officers 7 4 Organization 9 5 Domestic facilities 10 Industrial Products Company 6 Main Affiliates (Japan) 11 ※The Industrial Products Company will be integrated with the Subaru Automotive Business with effect from October 1, 2016. 7 Main Affiliates (Overseas) 12 1 Sales of General-Purpose Engines 32 8 Employees 13 2 Production of General-Purpose Engines 9 Facilities 14 (including on-board use) 32 3 Product Lineup 33 4 Specified dealers of Subaru products 33 Business Results 1 Consolidated Sales and Profits 15 2 Non-Consolidated Sales and Profits 16 Eco Technologies Company 34 3 Capital Expenditures, Depreciation and ※Eco Technology Company was discontinued in March R&D Expenses 16 2013. Share Information History 1 Share Information 17 1 Pre-Fuji Heavy Industries 35 2 Fuji Heavy Industries 36 NOTES: Automotive Business *The fiscal years stated in the Fact Book begin on April 1 of the previous year and end on March 31 of the year 1 Production 18 indicated. 2 Sales 20 3 Export 21 4 Brand Statement and Core Technologies 22 5 Product Lineup 25 6 Domestic sales agents 29 7 Overseas market overview 30 SUBARU Fact book 2016 2 Corporate Information 1 Profile Fuji Heavy Industries Ltd.(FHI) Name *FHI will change its company name to “SUBARU CORPORATION” with effect from April 1, 2017. -

SAE 2004 World Congress & Exhibition

SAE 2004 World Congress & Exhibition Technical Session Schedule As of 03/14/2004 08:00 pm Monday March, 8 Intelligent Vehicle Initiative (IVI) Technology - Advanced Controls Session Code: AE7 Room Dana Technical Innovation Forum Session Time: 9:00 a.m. Organizers - W. Riley Garrott, NHTSA; Frank S. Barickman, National Hwy Traffic Safety Admin Time Paper No. Title 9:00 a.m. 2004-01-1744 Functional Optimization of Adaptive Cruise Control Using Navigation Data Martin Brandstäter, Willibald Prestl, Günter Bauer, BMW Group 9:30 a.m. 2004-01-0170 Vehicle Speed Prediction for Driver Assistance Systems Mark Müller, Markus Reif, Madhukar Pandit, Technical Univ. of Kaiserslautern; Wolfgang Staiger, DaimlerChrysler AG; Bert Martin, DaimlerChrysler Corp. 10:00 a.m. 2004-01-0171 Modeling Driver Response to Lead Vehicle Decelerating Wassim G. Najm, U.S. DOT/Volpe Center; David L. Smith, U.S. Department of Transportation 10:30 a.m. 2004-01-0174 Intelligent Vehicles: The Next Generation in Vehicular Transportation Ronald H. Miller, Ford Motor Co. 11:00 a.m. 2004-01-0177 New Algorithm for Multiple Object Detection in FM-CW Radar Shunji Miyahara, Visteon Asia Pacific, Inc. 11:30 a.m. 2004-01-0175 Tracking a Preceding Vehicle for Adaptive Cruise Control Using a Block Matching Method Euiyoon Chung, Jeeyoung Kim, Hyundai & Kia Corp.; Eugene Chang, Hyundai Motor Co.; Jinmin Chun, Insik Lee, Hyundai & Kia Corp. 12:00 p.m. 2004-01-0179 Automotive Vision Platform Equipped With Dedicated Image Processor for Multiple Applications Shoji Muramatsu, Yuji Otsuka, Hiroshi Takenaga, Yoshiki Kobayashi, Tatsuhiko Monji, Hitachi Ltd. 2004-01-0180 Collaborative Driving Systems Adapted to Changing Environment Conditions (Written Only -- No Oral Presentation) Nicolas Gaubert, Univ.