V.90-1-Adding a Bit of Scientific Rigor to the Art of Finding and Appreciating

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Terroir of Wine (Regionality)

3/10/2014 A New Era For Fermentation Ecology— Routine tracking of all microbes in all places Department of Viticulture and Enology Department of Viticulture and Enology Terroir of Wine (regionality) Source: Wine Business Monthly 1 3/10/2014 Department of Viticulture and Enology Can Regionality Be Observed (Scientifically) by Chemical/Sensory Analyses? Department of Viticulture and Enology Department of Viticulture and Enology What about the microbes in each environment? Is there a “Microbial Terroir” 2 3/10/2014 Department of Viticulture and Enology We know the major microbial players Department of Viticulture and Enology Where do the wine microbes come from? Department of Viticulture and Enology Methods Quality Filtration Developed Pick Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) Nick Bokulich Assign Taxonomy 3 3/10/2014 Department of Viticulture and Enology Microbial surveillance: Next Generation Sequencing Extract DNA >300 Samples PCR Quantify ALL fungal and bacterial populations in ALL samples simultaneously Sequence: Illumina Platform Department of Viticulture and Enology Microbial surveillance: Next Generation Sequencing Department of Viticulture and Enology Example large data set: Bacterial Profile 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Winery Differences Across 300 Samplings 4 3/10/2014 Department of Viticulture and Enology Microbial surveillance process 1. Compute UniFrac distance (phylogenetic distance) between samples 2. Principal coordinate analysis to compress dimensionality of data 3. Categorize by metadata 4. Clusters represent samples of similar phylogenetic -

Viticulture and Winemaking Under Climate Change

agronomy Editorial Viticulture and Winemaking under Climate Change Helder Fraga Centre for the Research and Technology of Agro-Environmental and Biological Sciences, CITAB, Universidade de Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro, UTAD, 5000-801 Vila Real, Portugal; [email protected]; Tel.: +351-259-350-000 Received: 12 November 2019; Accepted: 19 November 2019; Published: 21 November 2019 Abstract: The importance of viticulture and the winemaking socio-economic sector is acknowledged worldwide. The most renowned winemaking regions show very specific environmental characteristics, where climate usually plays a central role. Considering the strong influence of weather and climatic factors on grapevine yields and berry quality attributes, climate change may indeed significantly impact this crop. Recent-past trends already point to a pronounced increase in the growing season mean temperatures, as well as changes in the precipitation regimes, which has been influencing wine typicity across some of the most renowned winemaking regions worldwide. Moreover, several climate scenarios give evidence of enhanced stress conditions for grapevine growth until the end of the century. Although grapevines have a high resilience, the clear evidence for significant climate change in the upcoming decades urges adaptation and mitigation measures to be taken by the sector stakeholders. To provide hints on the abovementioned issues, we have edited a special issue entitled: “Viticulture and Winemaking under Climate Change”. Contributions from different fields were considered, including crop and climate modeling, and potential adaptation measures against these threats. The current special issue allows the expansion of the scientific knowledge of these particular fields of research, also providing a path for future research. -

Structure in Wine Steiia Thiast

Structure in Wine steiia thiAst What is Structure? • So what is this thing, structure? It*s the sense you have that the wine has a well-established form,I think ofit as the architecture ofthe wine. A wine with a great structure will often remind me ofthe outlines of a cathedral, or the veins in a leaf...it supports, and balances the fiuit characteristics ofthe wine. The French often describe structure as the skeleton ofthe wine, as opposed to its flavor which they describe as the flesh. • Where does structure come firom? In white wines, it usually comes from alcohol or acidity; in red wines, it comes from a combination of acidity and tannin, a component in the grapes' skins and seeds. Thus, wines with a lot of tannin (like cabernet) also have a lot of structure. Beaujolais is made from gamay which does not have much tannin. As a result, Beaujolais can lack structure; it feels soft, flat or simple in the mouth (though its flavors can certainly still be attractive). • While structure is hard to articulate, you can easily taste or sense it —^and the lack of it. • Understanding structure is critical to understanding any ofthe ''powerful" red varieties: cabernet sauvignon, merlot, syrah, nebbiolo, tempranillo, and malbec, to name a few. I just don't think you can understand these wines unless you understand structure, and how it frames and focuses the powerful rush of fruit. It adds freshness, and a "lightness" to the density ofripe fiuit. Structure matters when pairing wine and food. Foods with a lot of structure themselves— like a meaty, thick steak-need wines with commensurate structure (like cabernet), or the food experience can dwarfthe wine experience. -

Starting a Vineyard in Texas • a GUIDE for PROSPECTIVE GROWERS •

Starting a Vineyard in Texas • A GUIDE FOR PROSPECTIVE GROWERS • Authors Michael C ook Viticulture Program Specialist, North Texas Brianna Crowley Viticulture Program Specialist, Hill Country Danny H illin Viticulture Program Specialist, High Plains and West Texas Fran Pontasch Viticulture Program Specialist, Gulf C oast Pierre Helwi Assistant Professor and Extension Viticulture Specialist Jim Kamas Associate Professor and Extension Viticulture Specialist Justin S cheiner Assistant Professor and Extension Viticulture Specialist The Texas A&M University System Who is the Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service? We are here to help! The Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service delivers research-based educational programs and solutions for all Texans. We are a unique education agency with a statewide network of professional educators, trained volunteers, and county offices. The AgriLife Viticulture and Enology Program supports the Texas grape and wine industry through technical assistance, educational programming, and applied research. Viticulture specialists are located in each region of the state. Regional Viticulture Specialists High Plains and West Texas North Texas Texas A&M AgriLife Research Denton County Extension Office and Extension Center 401 W. Hickory Street 1102 E. Drew Street Denton, TX 76201 Lubbock, TX 79403 Phone: 940.349.2896 Phone: 806.746.6101 Hill Country Texas A&M Viticulture and Fruit Lab 259 Business Court Gulf Coast Fredericksburg, TX 78624 Texas A&M Department of Phone: 830.990.4046 Horticultural Sciences 495 Horticulture Street College Station, TX 77843 Phone: 979.845.8565 1 The Texas Wine Industry Where We Have Been Grapes were first domesticated around 6 to 8,000 years ago in the Transcaucasia zone between the Black Sea and Iran. -

Terroir and Precision Viticulture: Are They Compatible ?

TERROIR AND PRECISION VITICULTURE: ARE THEY COMPATIBLE ? R.G.V. BRAMLEY1 and R.P. HAMILTON1 1: CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems, Food Futures Flagship and Cooperative Research Centre for Viticulture PMB No. 2, Glen Osmond, SA 5064, Australia 2: Foster's Wine Estates, PO Box 96, Magill, SA 5072, Australia Abstract Résumé Aims: The aims of this work were to see whether the traditional regionally- Objectifs : Les objectifs de ce travail sont de montrer si la façon based view of terroir is supported by our new ability to use the tools of traditionnelle d’appréhender le terroir à l'échelle régionale est confirmée Precision Viticulture to acquire detailed measures of vineyard productivity, par notre nouvelle capacité à utiliser les outils de la viticulture de précision soil attributes and topography at high spatial resolution. afin d’obtenir des mesures détaillées sur la productivité du vignoble, les variables du sol et la topograhie à haute résolution spatiale. Methods and Results: A range of sources of spatial data (yield mapping, remote sensing, digital elevation models), along with data derived from Méthodes and résultats : Différentes sources de données spatiales hand sampling of vines were used to investigate within-vineyard variability (cartographie des rendements, télédétection, modèle numérique de terrain) in vineyards in the Sunraysia and Padthaway regions of Australia. Zones ainsi que des données provenant d’échantillonnage manuel de vignes of characteristic performance were identified within these vineyards. ont été utilisées pour étudier la variabilité des vignobles de Suraysia et Sensory analysis of fruit and wines derived from these zones confirm that de Padthaway, régions d’Australie. -

Vineyard and Winery Information Series: VITICULTURE NOTES

Vineyard and Winery Information Series: VITICULTURE NOTES ........................ Vol. 25 No. 2, March - April, 2010 Tony K. Wolf, Viticulture Extension Specialist, AHS Jr. Agricultural Research and Extension Center, Winchester, Virginia [email protected] http://www.arec.vaes.vt.edu/alson-h-smith/grapes/viticulture/index.html I. Current situation .................................................................................. 1 II. Question from the field: replanting decisions ...................................... 2 III. Climbing cutworm update ..................................................................... 4 IV. New pesticides listed in 2010 PMG ...................................................... 5 V. Early season grape disease management .......................................... 7 VI. Upcoming meetings ............................................................................. 8 I. Current situation: Pest Management Guide (PMG) can be downloaded at: New Viticulture website: Cooperative http://pubs.ext.vt.edu/456/456-017/Section- Extension and Virginia Agricultural 3_Grapes-2.pdf Experiment Station websites were upgraded The pesticide recommendations are annually to a new server and hosting system which prepared by pest management specialists required a revision of content and change of with grape expertise at Virginia Tech, and URL. The new viticulture website is: form the basis of our grape pest http://www.arec.vaes.vt.edu/alson-h- management program. Pesticide smith/grapes/index.html recommendations augment cultural control -

Food Pairings: Viticulture Notes: Winemaking Notes

“WILD FERMENT” VINTED. 2018 TASTE: A clean, crisp, unoaked Chardonnay with flavors of apple, lemon meringue, pineapple, honey and hints of butter cream. The “wild” fermentation enhances both the aromatics and the fruit flavors, allowing the true varietal characteristics of Chardonnay to shine through. FOOD PAIRINGS: APPELLATION: This wines pairs wonderfully with roasted chicken or pork Clarksburg loin, any seafood dish, including lobster and crab, roasted root ALCOHOL: vegetables and creamy pasta dishes. !".#$ by Vol. RESIDUAL SUGAR: VITICULTURE NOTES: %.& g/!%% mL ($) The Chardonnay grape is one of the leading white grape PH: varieties in the world for production of high quality white ".#' wines. Its origins have been traced back to the Burgundy TOTAL ACIDITY: region of France, and it has been a part of the emerging (.% g/L as Tartaric Acid California wine industry since the late 1800’s. The Clarksburg HARVESTED: appellation is ideal for producing it, mainly due to its ideal September ", &%!) microclimate. Our vineyards enjoy warm Mediterranean-like BRIX AT HARVEST: weather, which allows for flavor development. They are also &".)˚ Brix Average exposed to cool maritime breezes that come in the evenings, BOTTLED: maintaining the grapes’ fresh acidity. January &!, &%&% WINEMAKING NOTES: PRODUCTION: "## cases Our “Wild Ferment” Chardonnay was made by harvesting the grapes in the cool morning, then quickly pressing the juice away from the grapes. The juice was cold settled in a chilled stainless steel tank, and racked off any solids. The juice was allowed to sit cold until a spontaneous fermentation began. After 30 days of fermentation, the wine was racked again, and allowed to sit on the natural yeast lees for several months before bottling. -

Fps Grape Program Newsletter

FPS GRAPE PROGRAM NEWSLETTER fps.ucdavis.edu OCT O BER 2012 From the Director: A Fruitful Year of Expansion by Deborah Golino On May 4, 2012, Foundation An ongoing major initiative for Plant Services supporters the FPS grapevine program is celebrated the dedication of the new Foundation Vineyard the Trinchero Family Estates at Russell Ranch. On page Building. We greatly enjoyed 14, Mike Cunningham details having so many stakeholders the vineyard preparations, join us for this special event. vine training and impressive Dean Neal Van Alfen welcomed numbers of qualified grapevines our guests; among them were added in 2012. Such progress Bob and Roger Trinchero In Progress: Trinchero Family Estates Building at FPS attests to the close cooperation representing the Trinchero Photo by Justin Jacobs of each person at FPS across family, donor Francis Mahoney, every function. Funding for this and the family of Pete Christensen, late Viticulture Foundation Vineyard was provided by the National Clean Specialist in the Department of Viticulture and Enology. Plant Network, a major new USDA program that benefits Having this event timed between the National Clean Plant clean plant centers for specialty crops at public institutions. Network Tier II Grapes annual meeting and Rose Day This is the final year of NCPN funding from the current allowed many distant guests to attend, including State farm bill. We hope that this program will continue to back and Federal regulatory officials, scientists from around us up as we fulfill our role as the foundation of registered the country, and many of our client nurseries. Photos of grapevine plants for growers and nurseries. -

Chardonnay Educator Guide

CHARDONNAY EDUCATOR GUIDE AUSTRALIAN WINE DISCOVERED PREPARING FOR YOUR CLASS THE MATERIALS VIDEOS As an educator, you have access to a suite of teaching resources and handouts, You will find complementary video including this educator guide: files for each program in the Wine Australia Assets Gallery. EDUCATOR GUIDE We recommend downloading these This guide gives you detailed topic videos to your computer before your information, as well as tips on how to best event. Look for the video icon for facilitate your class and tasting. It’s a guide recommended viewing times. only – you can tailor what you teach to Loop videos suit your audience and time allocation. These videos are designed to be To give you more flexibility, the following played in the background as you optional sections are flagged throughout welcome people into your class, this document: during a break, or during an event. There is no speaking, just background ADVANCED music. Music can be played aloud, NOTES or turned to mute. Loop videos should Optional teaching sections covering be played in ‘loop’ or ‘repeat’ mode, more complex material. which means they play continuously until you press stop. This is typically an easily-adjustable setting in your chosen media player. COMPLEMENTARY READING Feature videos These videos provide topical insights Optional stories that add from Australian winemakers, experts background and colour to the topic. and other. Feature videos should be played while your class is seated, with the sound turned on and SUGGESTED clearly audible. DISCUSSION POINTS To encourage interaction, we’ve included some optional discussion points you may like to raise with your class. -

Making White Wine from Fresh Grapes Basic Supplies Checklist from Curds and Wine

Making White Wine from Fresh Grapes Basic Supplies checklist from Curds and Wine Reference: 100 lbs grapes = 6-8 gallons finished wine Supplies listed in bold purple are for sale at Curds and Wine Supplies listed in bold red are for rent at Curds and Wine REFERENCES • The Winemakers Answer Book by Alison Crowe – A must-have for all of your questions during harvest and crush • Techniques in Home Winemaking by Daniel Pambianchi – most comprehensive guide to making wine from fresh grapes or concentrate • The Way to Make Wine by Sheridan Warrick – Step by step guide to making wine from fresh grapes EQUIPMENT • Refractometer (if growing grapes only; do NOT use after fermentation initiated to check brix!) • Manual Crusher or Motorized Crusher/destemmer • Wine press: basket press fine for 50-200 lbs grapes; bladder press for 100 lbs or more grapes • Primary fermentor: food grade container or carboy o 50-100 pounds of grapes: 7.9 gallon fermenting bucket or 6 gallon carboy o 200 pounds or more of grapes: multiple 32 gallon brute trash cans, or open pick bins • Hydrometer • Floating thermometer • Auto-siphon and tubing • Wine thief • Wine pump if using large volumes > 6 gallons • Secondary containers: o At least one 6-gallon carboy and bung/airlock per 100 lbs grapes o Will probably need ½ or 1 gallon jugs, might need 3 or 5 gallon carboys/Better Bottles o Variable capacity stainless steel tanks and assorted Hungarian barrels also available for large volumes • pH strips or pH meter; pH meter available for free testing at Curds and Wine INGREDIENTS -

Sauvignon Blanc: Past and Present by Nancy Sweet, Foundation Plant Services

Foundation Plant Services FPS Grape Program Newsletter October 2010 Sauvignon blanc: Past and Present by Nancy Sweet, Foundation Plant Services THE BROAD APPEAL OF T HE SAUVIGNON VARIE T Y is demonstrated by its woldwide popularity. Sauvignon blanc is tenth on the list of total acreage of wine grapes planted worldwide, just ahead of Pinot noir. France is first in total acres plant- is arguably the most highly regarded red wine grape, ed, followed in order by New Zealand, South Africa, Chile, Cabernet Sauvignon. Australia and the United States (primarily California). Boursiquot, 2010. The success of Sauvignon blanc follow- CULTURAL TRAITS ing migration from France, the variety’s country of origin, Jean-Michel Boursiqot, well-known ampelographer and was brought to life at a May 2010 seminar Variety Focus: viticulturalist with the Institut Français de la Vigne et du Sauvignon blanc held at the University of California, Davis. Vin (IFV) and Montpellier SupAgro (the University at Videotaped presentations from this seminar can be viewed Montpellier, France), spoke at the Variety Focus: Sau- at UC Integrated Viticulture Online http://iv.ucdavis.edu vignon blanc seminar about ‘Sauvignon and the French under ‘Videotaped Seminars and Events.’ clonal development program.’ After discussing the his- torical context of the variety, he described its viticultural HISTORICAL BACKGROUND characteristics and wine styles in France. As is common with many of the ancient grape varieties, Sauvignon blanc is known for its small to medium, dense the precise origin of Sauvignon blanc is not known. The clusters with short peduncles, that make it appear as if variety appears to be indigenous to either central France the cluster is attached directly to the shoot. -

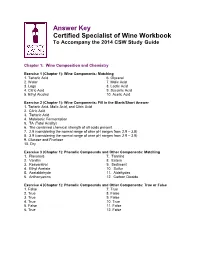

Answer Key Certified Specialist of Wine Workbook to Accompany the 2014 CSW Study Guide

Answer Key Certified Specialist of Wine Workbook To Accompany the 2014 CSW Study Guide Chapter 1: Wine Composition and Chemistry Exercise 1 (Chapter 1): Wine Components: Matching 1. Tartaric Acid 6. Glycerol 2. Water 7. Malic Acid 3. Legs 8. Lactic Acid 4. Citric Acid 9. Succinic Acid 5. Ethyl Alcohol 10. Acetic Acid Exercise 2 (Chapter 1): Wine Components: Fill in the Blank/Short Answer 1. Tartaric Acid, Malic Acid, and Citric Acid 2. Citric Acid 3. Tartaric Acid 4. Malolactic Fermentation 5. TA (Total Acidity) 6. The combined chemical strength of all acids present. 7. 2.9 (considering the normal range of wine pH ranges from 2.9 – 3.9) 8. 3.9 (considering the normal range of wine pH ranges from 2.9 – 3.9) 9. Glucose and Fructose 10. Dry Exercise 3 (Chapter 1): Phenolic Compounds and Other Components: Matching 1. Flavonols 7. Tannins 2. Vanillin 8. Esters 3. Resveratrol 9. Sediment 4. Ethyl Acetate 10. Sulfur 5. Acetaldehyde 11. Aldehydes 6. Anthocyanins 12. Carbon Dioxide Exercise 4 (Chapter 1): Phenolic Compounds and Other Components: True or False 1. False 7. True 2. True 8. False 3. True 9. False 4. True 10. True 5. False 11. False 6. True 12. False Exercise 5: Checkpoint Quiz – Chapter 1 1. C 6. C 2. B 7. B 3. D 8. A 4. C 9. D 5. A 10. C Chapter 2: Wine Faults Exercise 1 (Chapter 2): Wine Faults: Matching 1. Bacteria 6. Bacteria 2. Yeast 7. Bacteria 3. Oxidation 8. Oxidation 4. Sulfur Compounds 9. Yeast 5.