PGEG S4 04(B) Block 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

140926120027 Prospectus 201

1 C o t t o n College Prospectus Cotton College Prospectus 2 From the Principal As Cotton College moves into its one hundred and fourteenth year, it fondly recollects its contribution towards the field of higher education in North East India. A college that has produced stalwarts in fields ranging from scientific research through music to politics, Cotton College stands today to welcome a new generation of students. The college offers a host of facilities for its students. It has an extremely well stocked library with over one lakh twenty three thousand volumes and a special section for old and rare books-a unique feature for a college library. Besides, each department has its own specialized library catering to the needs of students of particular disciplines. Well equipped laboratories and museums serve every academic need of students. A gymnasium, an indoor stadium, activity hubs, counseling centres for academic, career and emotional counseling and facilities for sports and cultural activities ensure a healthy environment for the all-round development of each and every Cottonian. The college also boasts of an Entrepreneurship Development Cell which, besides providing self-employment avenues, also conducts courses in Mass Communication and Foreign Language. Its audio-visual studios have helped students to produce a number of excellent documentaries, short films, music albums as well as plays for the radio. Over the years Cotton College has provided a platform for a great many academicians, dignitaries, cultural icons and a host of other personalities to interact with its students, thereby exposing them to a larger world of positive human activity. -

Saurabh Kumar Chaliha

PGEG S4 04 (B) Exam Code : NEL Literature From North-East India (In English And Translation) SEMESTER IV ENGLISH BLOCK 2 KRISHNA KANTA HANDIQUI STATE OPEN UNIVERSITY Fiction (Block 2) 95 Subject Experts Prof. Pona Mahanta, Former Head, Department of English, Dibrugarh University Prof. Ranjit Kumar Dev Goswami, Former Srimanta Sankardeva Chair, Tezpur University Prof. Bibhash Choudhury, Department of English, Gauhati University Course Coordinators : Dr. Prasenjit Das, Associate Professor, Department of English, KKHSOU SLM Preparation Team UNITS CONTRIBUTORS 6-7, 9 Dr. Prasenjit Das 8 Dr. Kalpana Bora Department of English, Cotton University 10 Dr. Merry Baruah Bora Department of English, Cotton University Editorial Team Content: Unit 6,7 : Prof. Bibhash Choudhury Unit 8-10: Dr. Manab Medhi, Department of English, Bodoland University Structure, Format & Graphics: Dr. Prasenjit Das FEBRUARY, 2019 ISBN: 978-93-87940-93-2 © Krishna Kanta Handiqui State Open University This Self Learning Material (SLM) of the Krishna Kanta Handiqui State University is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-ShareAlike4.0 License (International) : http.//creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0 Printed and published by Registrar on behalf of the Krishna Kanta Handiqui State Open University. Headquarters: Patgaon, Rani Gate, Guwahati-781017 City Office: Housefed Complex, Dispur, Guwahati-781006; Web: www.kkhsou.in The University acknowledges with strength the financial support provided by the 96 Fiction (Block 2) Distance Education -

1 Wifistudy.Com

• Currency: Dollar • Prime Minister: Malcolm Turnbull By 2050, India will have most Muslims in world Ukraine region to use Russian ruble as currency By 2050, India will be the Ukraine's self-proclaimed Luhansk People's Republic will use country with the world's the Russian ruble as its official currency, according to an largest Muslim population, official statement. said American think tank The ruble would be used in the pro-Russian territory as the Pew Research Centre. basic unit of currency as of 1 March 2017, the statement While Islam is said. currently the world's The use of the ruble, which is already used informally in second-largest religion after Christianity, it is now also the the pro-Russian territory along with the Ukrainian hryvnia, fastest-growing major religion. serves to stabilise the volatile economic situation in the There were 1.6 billion Muslims in the world as of 2010 - region. roughly 23% of the global population - according to a Pew Ukraine estimate. Currently, Indonesia has the world's largest Muslim • Capital: Kiev population. • Currency: Hryvnia • Prime Minister: Volodymyr Groysman Syrian Army recaptures Palmyra from Islamic State • President: Petro Poroshenko The General Staff of the Syrian Army said it had recaptured the ancient city of Palmyra from the extremist group Islamic State Pakistan hosted 13th ECO Summit in Islamabad (IS). The 13th Economic Cooperation Organisation Summit was The city, which is home to Greco-Roman ruins on the held in Islamabad, Pakistan. United Nations cultural body’s World Heritage list, had The theme of ECO Summit was "Connectivity for been the scene of heavy fighting for months. -

B.A. Regular Course for Assamese Department of Assamese Bodoland University

B.A. Regular Course for Assamese Department of Assamese Bodoland University Course Structure of BA in Assamese (Regular) under Chaise Based Credit System (CBCS) and Continuous Assessment and Grading pattern (CAGP) SEME CORE COURSE (12) Ability Skill Elective Generic STER enhancement enhancement Discipline Elective compulsory Course (SEC) Specific- DSE GE-(2) course (2) (2) (4) English-I English I DSC-1(A): Introduction to Communication Assamese Folk Literature (AECC-I) DSC-2(A) from other (Compulsory) Subject MIL-I: Introduction to Environmental Assamese Poetry and Drama Science II DSC-1(B): Functional (AECC-2) Grammar of Assamese (compulsory) DSC-2(B) Other subject English-2 (SEC-1): III DSC-1(C): Study on Folklore and Assamese Prose and Tourism of Biography Assam DSC-2(C) Other subject IV MIL-2 Introduction to SEC-2: Assamese Prose, Short- story Uses of and Novel Language in DSC-1(D): Study on Culture Computer of Assam DSC-2(D): Other Subject (SEC-3): Study (DSE-1) GE1: V on Folk Study on Introducti Medicine of General on to Assam Linguistics Assamese literature (DSE-2): Other Subject (SEC-4): DSE-1 GE-2: VI Language of Assamese Short Introducti Printing and Story and on to Publishing Novel Assamese (DSE-2 ): Language and Other Subject Literature 1 Abbreviation Terms: C=Core AECC=Ability Enhancement Compulsory Course SEC=Skill Enhancement Course DSC=Discipline Specific Core Course DSE=Discipline Specific Elective GE=Generic Elective Semester-I Paper Code: 1.01R - English-1 Paper Code: AS1.02R-DSC-1(A): Introduction to Assamese Folk -

Print This Article

The world of Assamese celluloid: ‘yesterday and today’ Violet Barman Deka, Delhi University, [email protected] Volume 9. 1 (2021) | ISSN 2158-8724 (online) | DOI 10.5195/cinej.2021.358 | http://cinej.pitt.edu Abstract The study explores the entire journey of the Assamese cinema, which means a journey that will narrate many stories from its past and present, furthermore also will try to analyze its future potential. This paper deals with the trends emerging in genres, technical advancement, and visual representation along with a cult that emphasized the commercial success of cinema by toeing the style of Bollywood and world cinema. It explores the new journey of Assamese cinema, which deals with small budgets, realistic approaches, and portraying stories from the native lanes. It also touches upon the phase of ‘freeze’ that the Assamese cinema industry was undergoing due to global pandemic Covid-19. Keywords: Assamese cinema; Regional cinema; Jyotiprasad Agarwala; Regional filmmaker; Covid-19; OTT platform New articles in this journal are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 United States License. This journal is published by the University Library System of the University of Pittsburgh as part of its D-Scribe Digital Publishing Program and is cosponsored by the University of Pittsburgh Press The world of Assamese celluloid: ‘yesterday and today’ Voilet Barman Deka Introduction Is there any transformation in the craft of Assamese cinema or it is the same as it was in its beginning phase? Being a regional cinema industry, has the Assamese cinema been able to make its space in the creative catalog of Indian and world cinema? Is there anything radical that it has contributed towards the current and the next generation who is accepting and appreciating experimental cinema? This paper aims to explore the elongated journey of the Assamese cinema, a journey that will narrate many stories from its past and present as well analyze its future potential. -

MA-In-Assamese-CBCS-CO-2016.Pdf

GAUHATI UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF ASSAMESE PG Syllabus CBCS 2016 Syllabus Structure Course Code Semester Course First Semester ASM 1016 Rise and Development of Assamese Language C ASM 1026 History of Assamese Literature : 1889-2015 C ASM 1036 Study of Culture in Assam C ASM 1046 History of Sanskrit Literature: History, Features and Genres C ASM 1054 Creative Writing VA Second Semester ASM 2016 Assamese Poetry : 1889-2015 C ASM 2026 Assamese Prose : 1846-2015 C ASM 2036 Assamese Drama and Performance : 1857-2015 C ASM 2046 Indian Criticism C ASM 2054 Editing VA Third Semester Courses AS 3116 and AS 3126 are core (i.e., compulsory). Students shall choose one Elective Course from AS 3036, AS 3046, AS 3056, AS 3066 and AS 3076, and another from AS 3086, AS 3096, AS 3106, AS 3116 and AS 3126. Course AS 3126 will also be Elective Open ASM 3016 Assamese Novel: 1890-2015 C ASM 3026 Translation : Theory and Practice C ASM 3036 World Literature E ASM 3046 Ethnic Literature of North-East India E ASM 3056 Sanskrit Texts E ASM 3066 Varieties of Assamese Language E ASM 3076 Contact Languages of North-East India E ASM 3086 Modern Indian Literature E ASM 3096 Assamese Vaisnavite, Saiva and Sakta Literature E ASM 3106 Structure of the Assamese Language E 1 ASM 3116 Phonetics E ASM 3126 Sankaradeva Studies E/ EO Fourth Semester Courses AS 4016 and AS 4026 are core (i.e., compulsory). Students shall choose one elective course from AS 4036, AS 4046, AS 4056, AS 4066 and AS 4076, and another from AS AS 4086, AS 4096, AS 4106, AS 4116, AS 4126 and AS 4136. -

Department of English, Gauhati University Structure of B. A

Department of English, Gauhati University Structure of B. A. Programme and B.A. Honours in English under CBCS Outline of Choice Based Credit System: 1. Core Course: A course, which should compulsorily be studied by a candidate as a core requirement is termed as a Core course. 2. Elective Course: Generally a course which can be chosen from a pool of courses and which may be very specific or specialized or advanced or supportive to the discipline/ subject of study or which provides an extended scope or which enables an exposure to some other discipline/subject/domain or nurtures the candidate’s proficiency/skill is called an Elective Course. 2.1 Discipline Specific Elective (DSE) Course: Elective courses which may be offered by the main discipline/subject of study is referred to as Discipline Specific Elective. The University/Institute may also offer discipline related Elective courses of interdisciplinary nature (to be offered by main discipline/subject of study). 2.2 Dissertation/Project: An elective course designed to acquire special/advanced knowledge, such as supplement study/support study to a project work, and a candidate studying such a course on his own with an advisory support by a teacher/faculty member is called dissertation/project. 2.3 Generic Elective (GE) Course: An elective course chosen generally from an unrelated discipline/subject, with an intention to seek exposure is called a Generic Elective. P.S.: A core course offered in a discipline/subject may be treated as an elective by other discipline/subject and vice versa and such electives may also be referred to as Generic Elective. -

Gauhati University Syllabus for M.A. Semester Programme in Assamese

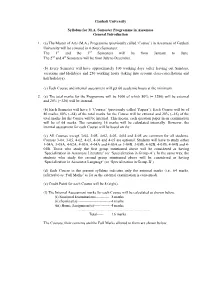

Gauhati University Syllabus for M.A. Semester Programme in Assamese General Introduction 1. (a) The Master of Arts (M.A.) Programme (previously called ‘Course’) in Assamese of Gauhati University will be covered in 4 (four) Semesters: The 1st and the 3rd Semesters will be from January to June. The 2nd and 4th Semesters will be from July to December. (b) Every Semester will have approximately 100 working days (after leaving out Sundays, vacations and Holidays) and 250 working hours (taking into account class-cancellations and half holidays). (c) Each Course and internal assessment will get 60 academic hours at the minimum. 2. (a) The total marks for the Programme will be 1600 of which 80% (= 1280) will be external and 20% (=320) will be internal. (b) Each Semester will have 5 ‘Courses’ (previously called ‘Papers’). Each Course will be of 80 marks. 80% (=64) of the total marks for the Course will be external and 20% (=16) of the total marks for the Course will be internal. This means, each question paper in an examination will be of 64 marks. The remaining 16 marks will be calculated internally. However, the internal assessment for each Course will be based on the (c) All Courses except 3-04, 3-05, 4-02, 4-03, 4-04 and 4-05 are common for all students. Courses 3-04, 3-05, 4-02, 4-03, 4-04 and 4-05 are optional. Students will have to study either 3-04A, 3-05A, 4-02A, 4-03A, 4-04A and 4-05A or 3-04B, 3-05B, 4-02B, 4-03B, 4-04B and 4- 05B. -

List of Candidates Who Have Applied Earlier for the Post of Jr. Assistant (District Level)

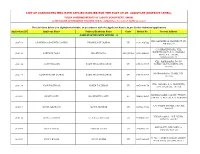

LIST OF CANDIDATES WHO HAVE APPLIED EARLIER FOR THE POST OF JR. ASSISTANT (DISTRICT LEVEL), UNDER COMMISSIONERATE OF LABOUR DEPARTMENT, ASSAM, AS PER EARLIER ADVERTISEMENT PUBLISHED VIDE NO. JANASANYOG/ D/11915/17, DATED 20-12-2017 The List Given below is in Alphabetical Order, in accordance with the Applicant Name ( As per Earlier Submited Application) Application ID Applicant Name Fathers/Husbands Name Caste Mobile No. Present Address NAME STARTING WITH LETTER: - 'A' VILL DAKSHIN MOHANPUR PT VII, 200718 A B MEHBOOB AHMED LASKAR NIYAMUDDIN LASKAR UR 9101308522 PIN 788119 C/O BRAJEN BORA, VILL. KSHETRI GAON, P.O. CHAKALA 206441 AANUPAM BORA BRAJEN BORA OBC/MOBC 9401696850 GHAT, P.S. JAJORI, NAGAON782142 VILL- MAIRAMARA, PO+PS- 200136 AASIF HUSSAIN ZAKIR HUSSAIN LASKAR UR 8753915707 HOWLY, DIST-BARPETA, PIN- 781316 MOIRAMARA PO-HOWLI, PIN- 200137 AASIF HUSSAIN LASKAR ZAKIR HUSSAIN LASKAR UR 8753915707 781316 VILL.-NAPARA, P.O.-HORUPETA, 200138 ABAN TALUKDAR NAREN TALUKDAR UR 9859404178 DIST.-BARPETA, 781318 NARENGI ASEB COLONY, TYPE IV, 203003 ABANI DOLEY KASHINATH DOLEY SC 7664836895 QTR NO. 4, GHY-26, P.O. NARENGI C/O SALMA STORES, GAR ALI, 202015 ABDUL GHAFOOR ABDUL MANNAN UR 8876215529 JORHAT VILL&P.O.&P.S.:- NIZ-DHING, 206442 ABDUL HANNAN LT. ABDUL MOTALIB UR 9706865304 NAGAON-782123 MAYA PATH, BYE LANE 1A, 203004 ABDUL HAYEE FAKHAR UDDIN UR 7002903504 SIXMILE, GHY-22 H. NO. 4, PEER DARGAH, SHARIF, 203005 ABDUL KALAM ABDUL KARIM UR 9435460827 NEAR ASEB, ULUBARI, GHY 7 HATKHOLA BONGALI GAON, CHABUA TATA GATE, LITTLE AGEL 201309 ABDUL KHAN NUR HUSSAIN KHAN UR 9678879562 SCHOOL ROAD, CHABUA, DIST DIBRUGARH 786184 BIRUBARI SHANTI PATH, H NO. -

Mcqs for COMPETITIVE EXAMS KEY to CRACK EXAMS B) 1826 C) 1830 D) 1832 9

KEY TO CRACK EXAMS 1. The first conference of Assam Sahitya Sabha was held at A) Kamrup B) Sivasagar C) Barpeta D) Dhuburi 2. Who was the first President of Assam Sahitya Sabha A) Lakshminath Bezbaroa B) Padmanath Gohain Baruah C) Hemchandra Goswami D) Rajanikanta Bordoloi 3. Total number of National Parks in Assam A) 3 B) 4 C) 5 D) 7 4. Total number of bridges over the river Brahmaputra A) 4 B) 5 C) 6 D) 7 5. The Naranarayan Setu connects the Pancharatna Town with which city A) Kalibor B) Tezpur C) Bongaigaon D) Jogighopa 6. Who was the first Chief Minister of Assam? A) Bishnuram Medhi B) Tarun Ram Phukan C) Gopinath Bordoloi D) None of the Above 7. Who was the last king of Ahom kingdom in Assam? A) Gobar Roja B) Sutanphaa C) Purandar Singha D) Jogeswar Singha 8. The Treaty of Yandabo was signed in the year A) 1802 2 MCQs FOR COMPETITIVE EXAMS KEY TO CRACK EXAMS B) 1826 C) 1830 D) 1832 9. .Which one is the first assamese novel? A) Mirijiyori B) Podum Kunwari C) Bhanumati D) Sudharmar Upakhyan 10. The state anthem "O Mur Apunar Desh" was first published in the magazine named A) Bahi B) Jonaki C) Surabhi D) Jonbiri 11. The first Assamese magazine Orunodoi was published in the year A) 1836 B) 1846 C) 1872 D) 1882 12. Who is the first barrister of Assam? A) Haliram Deka B) Pranab kumar Borooah C) Anundoram Borooah D) Parul Das 13. Which one is the largest district in Assam by area wise? A) Barpeta B) Karbi Anglong C) Sivsagar D) Dibrugarh 14. -

Dr. Jyoti Prasad Medhi: an Eminent Assamese Mathematician and My Thoughts - 02-17-2018 by Priyankush Deka - Gonit Sora

Dr. Jyoti Prasad Medhi: An Eminent Assamese Mathematician and my Thoughts - 02-17-2018 by Priyankush Deka - Gonit Sora - https://gonitsora.com Dr. Jyoti Prasad Medhi: An Eminent Assamese Mathematician and my Thoughts by Priyankush Deka - Saturday, February 17, 2018 https://gonitsora.com/jyoti-prasad-medhi/ The list of Assamese scholar who has contributed significantly in the field of mathematical science and is renowned internationally is quite short. Therefore, any news of an Assamese receiving international recognition for their talent and intelligence receives immense importance and attention. They not only make our state and country proud internationally, but their examples inspire our new generation to walk ahead working hard. Today, the person going to be described here is one such eminent Assamese statistician who has established himself internationally: Dr. Jyoti Prasad Medhi. The very first time I heard the name of Dr. Medhi, I developed an instant interest over him. Once, a picture of Dr. Medhi being honoured with Dr. APJ Abdul Kalam in Tezpur University caught my attention. That was the first time I came to know the name of Dr. Jyoti Prasad Medhi. As far as I remember, the picture was published about 6 years ago in the supplement of the Assamese daily; ‘Amar Axom’ called ‘Bohumukh’. The picture was captured in 2001 when Dr. APJ Abdul Kalam and Dr. Jyoti Prasad Medhi was conferred with D.Litt. and D.Sc. titles in the Convocation ceremony of Tezpur University respectively. Since then I gave ardently admired Dr. Medhi and was greatly interested in knowing more about him. I felt proud as an Assamese in knowing that in spite of continuing his work life in Assam, he kept on doing internationally a acclaimed research and publishing books which brought him great fame and admiration. -

Applicants for Posts of Ward Boy & Ward

As per Advertisement No. Janasanyog/2665/15, dtd.15/06/2015 the list of candidate who have already applied for the post of Ward Boy/Ward Girl has been listed bellow and they need not apply again: Name & Address Sl. No. SURJYA BHANU, ABDUL SALAM, VILL- 1 BALARCHAR, P.O- KIRTANPARA, DIST- BANGAIGAON, ASSAM, PIN-780084 MITALI DEVI, LT. HARENDRA NATH SARMA, 2 CHRISTANBASTI UDAYACHALSAMMONNAY PATH, H. NO- 15, P.O- DISPUR, GHY-5 SHRI HIMANGSHU NATH, C/O- SHRI SUKLESHWAR NATH, P.O- 3 BAMUNIMAIDAN, DIST- KAMRUP,ASSAM, GHY-3, PIYALI PHUKAN NAGAR SRI MANAB DAS, C/O- SRI NAGESWAR DAS, 4 VILL- MAJPARA, P.O- CHAYGAON, DIST- KAMRUP,ASSAM, PIN-781124 SRI KISHOR MEDHI, C/O- PRAHLAD MEDHI, 5 VILL+P.O- KHAGROBARI, DIST- BAKSA, ASSAM, PIN-781344 SUSMITA DEVI DEKA, C/O- BISHNU SARMA, PIYALI PHUKAN PATH, P.O- 6 BAMUNIMAIDAN, DIST- KAMRUP, ASSAM, GHY-3 Page 1 of 926 SRI SHANJIT KAIBARTA, C/O- ABHI RAM KAIBARTA, VILL- GARGARA, P.O- 7 SIKARHATI, DIST- KAMRUP,ASSAM, PIN- 781125 MONAJ NAG, C/O- MANIK CH. NAG, 8 ADABARI TINIALI G.R.P. RESERVE LANE BARIPARA, PIN-781012 DIPANKAR DAS, C/O- ANIL DAS, PANDU TEMPLE GHAT, NEAR QR. NO-9/B, P.O- 9 PANDU REST CAMO, DIST- KAMRUP, ASSAM,PIN-781012 ASHRAFUL HAQUE, C/O- LT. SAIFUDDIN 10 AHMED, VILL+P.O- KALITAKUCHI, DIST- KAMRUP,ASSAM, PIN-781102 RATUL CHANDRA BARO, C/O- LT. CHANA RAM BARO, VILL-JAJIKANA, P.O- 11 MODHUKUCHI, DIST- KAMRUP,ASSAM, PIN- 781354 ANJUMA BEGUM, C/O- ATOWAR RAHMAN, 12 VILL- KACHARIPETY PT-II, P.O- AMBARI, PIN-783384 SANJIT BISWAS, C/O- LT.