The Rite of Spring: a Failure and a Triumph

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 4-30-2011 Concert: Ithaca College Symphony Orchestra Jeffery Meyer Ithaca College Symphony Orchestra Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Meyer, Jeffery and Ithaca College Symphony Orchestra, "Concert: Ithaca College Symphony Orchestra" (2011). All Concert & Recital Programs. 232. http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/232 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. Ithaca College Symphony Orchestra Jeffery Meyer, conductor Susan Waterbury, violin Elizabeth Simkin, cello Jennifer Hayghe, piano Ford Hall Saturday, April 30, 2011 4:00 p.m. Program White Lies for Lomax (2008) Mason Bates (1977) Concerto for Piano, Violin, Violoncello, and Ludwig van Beethoven Orchestra in C major, Op. 56 (1770-1827) Allegro Largo Finale: Rondo alla Polacca Susan Waterbury, violin Elizabeth Simkin, cello Jennifer Hayghe, piano Intermission Le sacre du printemps (The Rite of Spring) Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) Part I: L’adoration de la Terre (The adoration of the earth) Introduction Danse des Adolescentes (Dance of the young girls) Jeu du Rapt (Ritual of Abduction) Rondes Printaniéres (Spring rounds) Jeu des Cités Rivales (Ritual of the rival tribes) Cortège du Sage (Procession -

Program Notes by Dr

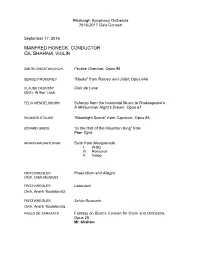

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra 2016-2017 Gala Concert September 17, 2016 MANFRED HONECK, CONDUCTOR GIL SHAHAM, VIOLIN DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH Festive Overture, Opus 96 SERGEI PROKOFIEV “Masks” from Romeo and Juliet, Opus 64a CLAUDE DEBUSSY Clair de Lune Orch. Arthur Luck FELIX MENDELSSOHN Scherzo from the Incidental Music to Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Opus 61 RICHARD STAUSS “Moonlight Scene” from Capriccio, Opus 85 EDVARD GREIG “In the Hall of the Mountain King” from Peer Gynt ARAM KHACHATURIAN Suite from Masquerade I. Waltz IV. Romance V. Galop FRITZ KREISLER Praeludium and Allegro Orch. Clark McAlister FRITZ KREISLER Liebesleid Orch. André Kostelanetz FRITZ KREISLER Schön Rosmarin Orch. André Kostelanetz PABLO DE SARASATE Fantasy on Bizet’s Carmen for Violin and Orchestra, Opus 25 Mr. Shaham Sept. 17, 2016, page 1 PROGRAM NOTES BY DR. RICHARD E. RODDA DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH (1906-1975) Festive Overture, Opus 96 (1954) Among the grand symphonies, concertos, operas and chamber works that Dmitri Shostakovich produced are also many occasional pieces: film scores, tone poems, jingoistic anthems, brief instrumental compositions. Though most of these works are unfamiliar in the West, one — the Festive Overture — has been a favorite since it was written in the autumn of 1954. Shostakovich composed it for a concert on November 7, 1954 commemorating the 37th anniversary of the Russian Revolution, but its jubilant nature suggests it may also have been conceived as an outpouring of relief at the death of Joseph Stalin one year earlier. One critic suggested that the Overture was “a gay picture of streets and squares packed with a young and happy throng.” As its title suggests, the Festive Overture is a brilliant affair, full of fanfare and bursting spirits. -

Teacher Notes on Russian Music and Composers Prokofiev Gave up His Popularity and Wrote Music to Please Stalin. He Wrote Music

Teacher Notes on Russian Music and Composers x Prokofiev gave up his popularity and wrote music to please Stalin. He wrote music to please the government. x Stravinsky is known as the great inventor of Russian music. x The 19th century was a time of great musical achievement in Russia. This was the time period in which “The Five” became known. They were: Rimsky-Korsakov (most influential, 1844-1908) Borodin Mussorgsky Cui Balakirev x Tchaikovsky (1840-’93) was not know as one of “The Five”. x Near the end of the Stalinist Period Prokofiev and Shostakovich produced music so peasants could listen to it as they worked. x During the 17th century, Russian music consisted of sacred vocal music or folk type songs. x Peter the Great liked military music (such as the drums). He liked trumpet music, church bells and simple Polish music. He did not like French or Italian music. Nor did Peter the Great like opera. Notes Compiled by Carol Mohrlock 90 Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky (1882-1971) I gor Stravinsky was born on June 17, 1882, in Oranienbaum, near St. Petersburg, Russia, he died on April 6, 1971, in New York City H e was Russian-born composer particularly renowned for such ballet scores as The Firebird (performed 1910), Petrushka (1911), The Rite of Spring (1913), and Orpheus (1947). The Russian period S travinsky's father, Fyodor Ignatyevich Stravinsky, was a bass singer of great distinction, who had made a successful operatic career for himself, first at Kiev and later in St. Petersburg. Igor was the third of a family of four boys. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 68, 1948-1949

(fr) BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA FOUNDED IN 1881 BY HENRY LEE HIGGINSON Vk [Q m A* ^5p — H & #i SIXTY-EIGHTH SEASON 1948-1949 Tuesday Evening Series Boston Symphony Orchestra [Sixty-eighth Season, 1948-1949] SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY, Music Director RICHARD BURGIN, Associate Conductor PERSONNEL Violins Violas Bassoons Richard Burgin, Joseph de Pasquale Raymond Allard Concert-master Jean Cauhap6 Ernst Panenka Alfred Krips Georges Fourel Ralph Masters Gaston Elcus Eugen Lehner Rolland Tapley Albert Bernard Contra-Bassoon Norbert Lauga Emil Kornsand Boaz Piller George Zazofsky George Humphrey Paul Cherkassky Louis Artieres Horns Harry Dubbs Charles Van Wynbergen Willem Valkenier Vladimir Resnikoff Hans Werner James Stagliano Principals Joseph Leibovici Jerome Lipson Harry Einar Hansen Siegfried Gerhardt Shapiro Harold Daniel Eisler Meek Violoncellos Paul Keaney Norman Carol Walter Macdonald Carlos P infield Samuel Mayes Osbourne McConath) Paul Fedorovsky Alfred Zighera Harry Dickson Jacobus Langendoen Trumpets Minot Beale Mischa Nieland Georges Mager Frank Zecchino Hippolyte Droeghmans Roger Voisin Karl Zeise Principals Clarence Knudson Josef Zimbler Marcel La fosse Pierre Mayer Bernard Parronchi Harry Herforth Manuel Zung Enrico Fabrizio Ren£ Voisin Samuel Diamond Leon Marjollet Victor Manusevitch Trombones James Nagy Flutes Jacob Raichman Leon Gorodetzky Georges Laurent Lucien Hansotte Raphael Del Sordo James Pappoutsakis John Coffey Melvin Bryant Phillip Kaplan Josef Orosz John Murray Piccolo Tuba Lloyd Stonestreet Vinal Smith Henri Erkelens George -

Paris Modern the Swedish Ballet 1920-1925

PARIS MODERN THE SWEDISH BALLET 1920-1925 Nancy Vim Norman Baer with contributions by Jan Torsten Ahlstrand William Camfield Judi Freeman Lynn Garafola Gail Levin Robert~.~urdock Erik Naslund Anna Greta Stahle FINE ARTS MUSEUMS OF SAN FRANCISCO Distributed by the University of Washington Press ~~ETS SJ". ~~ v~ .:z;.~ ~0 f.... ~ RIVALS FOR THE NE-W Lynn Garafola n the early 192 0S the Ballets Russes faced a rival had been a "turn" on the English music-hall stage, while that challenged its monopoly of avant-garde ballet its grand postwar comeback at the Paris Opera early in I -the Ballets Suedois. Organized by Rolf de Mare, 1920 had been marred by a two-week strike of Opera the new company made its debut at the Theatre des personnel. And where the opening season of the Ballets Champs-Elysees on 25 October 1920 with an ambitious Suedois would offer fifty-odd performances, the Ballets program of works choreographed by Jean Borlin, the Russes season that followed would consist of fewer than company's star. Four ballets were given on the opening a dozen. night-Iberia, Jeux (Games), Derviches (Dervishes), and Still, Diaghilev must have found some consolation in Nuit de Saint-Jean (Saint John's Night, or Midsummer the identity-or lack of identity-of the rival enterprise. Night's Revel)-and in the course of the season, which To all appearances the new company was a knock-off of lasted for nearly six weeks, five new ones were added the Ballets Russes, from its name, which meant "Swedish Diver1:isse71lent, Maison de flus (Madhouse), Le To71lbeau Ballet," to its repertory, roster of collaborators, and de Couperin (The Tomb of Couperin), El Greco, and Les general aesthetic approach. -

Sergei Prokofiev

Sergei Prokofiev Sergei Sergeyevich Prokofiev (/prɵˈkɒfiɛv/; Russian: Сергей Сергеевич Прокофьев, tr. Sergej Sergeevič Prokof'ev; April 27, 1891 [O.S. 15 April];– March 5, 1953) was a Russian composer, pianist and conductor. As the creator of acknowledged masterpieces across numerous musical genres, he is regarded as one of the major composers of the 20th century. His works include such widely heard works as the March from The Love for Three Oranges, the suite Lieutenant Kijé, the ballet Romeo and Juliet – from which "Dance of the Knights" is taken – and Peter and the Wolf. Of the established forms and genres in which he worked, he created – excluding juvenilia – seven completed operas, seven symphonies, eight ballets, five piano concertos, two violin concertos, a cello concerto, and nine completed piano sonatas. A graduate of the St Petersburg Conservatory, Prokofiev initially made his name as an iconoclastic composer-pianist, achieving notoriety with a series of ferociously dissonant and virtuosic works for his instrument, including his first two piano concertos. In 1915 Prokofiev made a decisive break from the standard composer-pianist category with his orchestral Scythian Suite, compiled from music originally composed for a ballet commissioned by Sergei Diaghilev of the Ballets Russes. Diaghilev commissioned three further ballets from Prokofiev – Chout, Le pas d'acier and The Prodigal Son – which at the time of their original production all caused a sensation among both critics and colleagues. Prokofiev's greatest interest, however, was opera, and he composed several works in that genre, including The Gambler and The Fiery Angel. Prokofiev's one operatic success during his lifetime was The Love for Three Oranges, composed for the Chicago Opera and subsequently performed over the following decade in Europe and Russia. -

Stravinsky and the Octatonic: a Reconsideration

Stravinsky and the Octatonic: A Reconsideration Dmitri Tymoczko Recent and not-so-recent studies by Richard Taruskin, Pieter lary, nor that he made explicit, conscious use of the scale in many van den Toorn, and Arthur Berger have called attention to the im- of his compositions. I will, however, argue that the octatonic scale portance of the octatonic scale in Stravinsky’s music.1 What began is less central to Stravinsky’s work than it has been made out to as a trickle has become a torrent, as claims made for the scale be. In particular, I will suggest that many instances of purported have grown more and more sweeping: Berger’s initial 1963 article octatonicism actually result from two other compositional tech- described a few salient octatonic passages in Stravinsky’s music; niques: modal use of non-diatonic minor scales, and superimposi- van den Toorn’s massive 1983 tome attempted to account for a tion of elements belonging to different scales. In Part I, I show vast swath of the composer’s work in terms of the octatonic and that the rst of these techniques links Stravinsky directly to the diatonic scales; while Taruskin’s even more massive two-volume language of French Impressionism: the young Stravinsky, like 1996 opus echoed van den Toorn’s conclusions amid an astonish- Debussy and Ravel, made frequent use of a variety of collections, ing wealth of musicological detail. These efforts aim at nothing including whole-tone, octatonic, and the melodic and harmonic less than a total reevaluation of our image of Stravinsky: the com- minor scales. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 43,1923-1924, Trip

CARNEGIE HALL .... NEW YORK Thursday Evening, March 13, at 8.15 Saturday Afternoon, March 1 5, at 2.30 £*WHififl% >n\V"' y f/ BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA INC. FORTY-THIRD SEASON J923-J924 PRoGRTWIE '4 '« — An Audience worth cultivating Because it reaches an audience of unusual potentiality, The Boston Symphony Orchestra Programme is a most effective media for a limited number of advertisers. This audience is composed of people of taste, culture and means. They are interested, essentially, in the better things of life. They can, and do, purchase generously — but discriminately. The BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Programme is mailed to the home of this audience. The descriptive notes by Mr. Philip Hale, foremost of critics, secures for the Programme a place among works of reference and gives to it an unusual permanence. Your advertising message will thus have many times the value generally attributed to publicity advertising. If your product — or service — will appeal to this discriminating audience Write for Rates Jiddress GARDNER and STORR L8fi MADISON AVI NEW YORK CITY Phone, Ashland 6280 CARNEGIE HALL NEW YORK Thirty-eighth Season in New York FORTY-THIRD SEASON, 1923-1924 INC. PIERRE MONTEUX, Conductor THURSDAY EVENING, MARCH 13, at 8.15 AND THE SATURDAY AFTERNOON, MARCH 15, at 2.30 WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE COPYRIGHT, 1924, BY BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, INC. THE OFFICERS AND TRUSTEES OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. FREDERICK P. CABOT President GALEN L. STONE ...... Vice-President ERNEST B. DANE Treasurer ALFRED L. AIKEN ARTHUR LYMAN FREDERICK P. CABOT HENRY B. SAWYER ERNEST B. -

Modernism in Visual Arts and Music

HUM 102 Cultural Encounters II Modernism in Visual Arts and Music Rana Gediz İren Boğaziçi University İstanbul Philharmonic Society Arts in Europe 1900-1945 Artists began to emphasise the extreme expressive properties of pictorial form to explore subjective emotions and inner psychological truths while composers of Classical Music turned to radical new ways of expressing melody, harmony and rhythm Sigmund Freud (1856-1839) • Austrian neurologist who is the founder of psychoanalysis. • The Interpretation of Dreams (1900). • Explorations of the role of sexuality and the subconscious. Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) • German philosopher and cultural critic. His writings on truth, morality, aesthetics, cultural theory, nihilism, consciousness, and the meaning of existence have exerted an enormous influence on Western philosophy and intellectual history. • Metaphor of the “Bridge”: Mankind as a bridge between the animal and the superman/overman. Emil Nolde (1867-1956), Self Portrait, 1947 Modernism in Germany - Expressionism • Developed in pre-WW1 Years. • Characterised by simplified shapes, bright colours and gestural marks or brushstrokes. • The image of reality is distorted in order to make it expressive of the artist’s inner feelings or ideas. • Concerned with the contemporary psychological situation. Confession of moods of anxiety, frustration and resentment towards the modern world. Die Brücke (The Bridge) – Dresden 1905 Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) – Munich 1911 “We call all young people together and as young people who carry the -

Rite of Spring' Dance Reveals Perils of Progress June 18, 2012 |

'Rite of Spring' dance reveals perils of progress June 18, 2012 | Rebecca McLindon of the Eisenhower Dance Ensemble dances Saturday in "The Rite of Spring." / Natalie Bruno By Mark Stryker Detroit Free Press Music Critic Of the many striking images choreographer Laurie Eisenhower creates in her newly conceived "The Rite of Spring," a sweeping parable about the double-edged sword of human "progress," one in particular continues to resonate in the aftermath of Saturday's Great Lakes Chamber Music Festival premiere. Four dancers sit with their backs to the audience, staring like drugged zombies at hypnotizing rectangles of light -- televisions -- symbols of the dehumanizing effects of technology. Meanwhile, a solo dancer, Rebecca McLindon, twirls exuberantly around the others, a beacon of eloquent self-expression and humanity amidst the mechanized wasteland. Igor Stravinsky's visceral score breathes life into her. The message seems to be that if we have any chance at all, art and the individual imagination will be our salvations. The Great Lakes festival reached its midpoint with Stravinsky's famous "Rite." The festival collaborated with the Eisenhower Dance Ensemble to bring the work to the stage. This was one of the largest undertakings in Great Lakes history, but the ambition paid off handsomely in an inventive production that aimed high and often soared higher. A number of major Stravinsky works are at the core of the 2012 festival, but the status of "The Rite of Spring" (1913) as a modernist icon and the rare chance to see a fully staged production held special allure. Stravinsky's piano four-hands reduction of his massive orchestral score provided the backbone. -

Yannick Nézet-Séguin

This season, this orchestra, this music director, this performance, this moment ... don’t blink. 2020–21 SEASON MUSIC DIRECTOR YANNICK NÉZET-SÉGUIN 1 Welcome to Your Philadelphia Orchestra’s 2020-21 Season Our World NOW is both a visit to the music you know and love and a vision of familiar works heard and perceived in new ways. In this chronological listing of concerts, we invite you to Choose Your Own season of music to fit your tastes, your schedule, and your budget. Pick any six (or more) and relax knowing that you have reserved time in your life for enjoyment, escape, and invigoration. Choose a Create-Your-Own 6-concert series for as little as $39 per concert. Create your own season of music at a savings over individual ticket prices when you subscribe today. Schedule Flexibility Always on the go? We offer subscribers many easy options to exchange tickets with no additional fees so you never Subscriber Benefits have to miss a concert. Everyday Savings Subscribing automatically saves you money over general public single ticket prices. Save up to 20% off single ticket prices depending on the concert and section you choose. Plus, add tickets and the savings continue. Payment Plans There are several payment plans to fit any budget, making it easy to subscribe. Order early, take advantage of our payment plans, and still get the best seats. Discounted Parking Why worry about finding a place to park? As a subscriber, you can purchase pre-paid discounted parking for all your concerts in the Avenue of the Arts Garage, located steps away from the Kimmel Center. -

Branding Brussels Musically: Cosmopolitanism and Nationalism in the Interwar Years

BRANDING BRUSSELS MUSICALLY: COSMOPOLITANISM AND NATIONALISM IN THE INTERWAR YEARS Catherine A. Hughes A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2015 Approved by: Annegret Fauser Mark Evan Bonds Valérie Dufour John L. Nádas Chérie Rivers Ndaliko © 2015 Catherine A. Hughes ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Catherine A. Hughes: Branding Brussels Musically: Cosmopolitanism and Nationalism in the Interwar Years (Under the direction of Annegret Fauser) In Belgium, constructions of musical life in Brussels between the World Wars varied widely: some viewed the city as a major musical center, and others framed the city as a peripheral space to its larger neighbors. Both views, however, based the city’s identity on an intense interest in new foreign music, with works by Belgian composers taking a secondary importance. This modern and cosmopolitan concept of cultural achievement offered an alternative to the more traditional model of national identity as being built solely on creations by native artists sharing local traditions. Such a model eluded a country with competing ethnic groups: the Francophone Walloons in the south and the Flemish in the north. Openness to a wide variety of music became a hallmark of the capital’s cultural identity. As a result, the forces of Belgian cultural identity, patriotism, internationalism, interest in foreign culture, and conflicting views of modern music complicated the construction of Belgian cultural identity through music. By focusing on the work of the four central people in the network of organizers, patrons, and performers that sustained the art music culture in the Belgian capital, this dissertation challenges assumptions about construction of musical culture.