Download File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chic Monte-Carlo 2020

PANTONE 7408 / PANTONE BLACK LE MONACO ART & CULTURE LE MONACO ART & CULTURE Durée de la promenade Une journée ou plus 1 Départ Durée1. Cabanon de Le Corbusier la2. promenadeCasino de Monte-Carlo Une journée ou plus 3. Déjeuner au Castelroc 1 Départ4. Cathédrale de Monaco 1.5. CabanonPalais Princier Le Corbusier 2.6. CasinoVilla Sauber de Monte-Carlo et/ou Villa 3.Paloma Déjeuner au Castelroc 4.7. BarCathédrale Américain de deMonaco l’Hôtel 5.de Palais Paris Monte-CarloPrincier 6. Villa Sauber et/ou Villa Paloma 10 11 7. Bar Américain de l’Hôtel de Paris Monte-Carlo 10 11 LE MONACO ROMANTIQUE Durée de la promenade Une journée 1 Départ 1. Petit déjeuner à l’Hôtel Hermitage Monte-Carlo 2. Visite de la Roseraie Princesse Grace 3. Vol panoramique en hélicoptère 4. Déjeuner au restaurant Ômer 5. Thermes Marins Monte-Carlo 6. Sunset cruise 7. Dîner à la Vigie au Monte-Carlo Beach 106 107 LE MONACO DES KIDS LE MONACO DES KIDS Sporting Monte-Carlo Sporting Monte-Carlo Forum Grimaldi Forum Grimaldi Le Casino Thermes Marins Monte-Carlo Monte-Carlo Le Casino Thermes Marins Monte-Carlo Monte-Carlo Palais Princier Durée de Palais Princier la promenadeDurée de Unela promenadejournée Une journée 1 Départ 1 1. CollectionDépart de voitures de1. S.A.S Collection le Prince de Albertvoitures II Musée Océanographique dede Monaco S.A.S le Prince Albert II Musée Océanographique 2. deJardin Monaco animalier de Monaco2. Jardin animalier de 3. MonacoLe Stars’n Bars 4. 3.Musée Le Stars’n Océanogra Bars - phique4. Musée Océanogra- 5. -

Download Chapter (PDF)

PLATES 1. Cole Porter, Yale yearbook photograph (1913). 2. Westleigh Farms, Cole Porter’s childhood home in Indiana (2011). 3. Cole Porter’s World War I draft registration card (5 June 1917). War Department, Office of the Provost Marshal General. 4. Linda Porter, passport photograph (1919). 5. Cole Porter, Linda Porter, Bernard Berenson and Howard Sturges in Venice (c.1923). 6. Gerald Murphy, Ginny Carpenter, Cole Porter and Sara Murphy in Venice (1923). 7. Serge Diaghilev, Boris Kochno, Bronislava Nijinska, Ernest Ansermet and Igor Stravinsky in Monte Carlo (1923). Library of Congress, Music Division, Reproduction number: 200181841. 8. Letter from Cole Porter to Boris Kochno (September 1925). Courtesy of The Cole Porter Musical and Literary Property Trusts. 9. Scene from the original stage production of Fifty Million Frenchmen (1929). PHOTOFEST. 10. Irene Bordoni, star of Porter’s show Paris (1928). 11. Sheet music, ‘Love for Sale’ from The New Yorkers (1930). 12. Production designer Jo Mielziner showing a set for Jubilee (1935). PHOTOFEST. 13. Cole Porter composing as he reclines on a couch in the Ritz Hotel during out-of-town tryouts for Du Barry Was a Lady (1939). George Karger / Getty Images. 14. Cole and Linda Porter (c.1938). PHOTOFEST. 15. Ethel Merman in the New York production of Cole Porter’s Panama Hattie (1940). George Karger / Getty Images. vi PLATES 16. Sheet music, ‘Let’s Be Buddies’ from Panama Hattie (1940). 17. Draft of ‘I Am Ashamed that Women Are So Simple’ from Kiss Me, Kate (1948), Library of Congress. Courtesy of The Cole Porter Musical and Literary Property Trusts. -

Extended Sensibilities Homosexual Presence in Contemporary Art

CHARLEY BROWN SCOTT BURTON CRAIG CARVER ARCH CONNELLY JANET COOLING BETSY DAMON NANCY FRIED EXTENDED SENSIBILITIES HOMOSEXUAL PRESENCE IN CONTEMPORARY ART JEDD GARET GILBERT & GEORGE LEE GORDON HARMONY HAMMOND JOHN HENNINGER JERRY JANOSCO LILI LAKICH LES PETITES BONBONS ROSS PAXTON JODY PINTO CARLA TARDI THE NEW MUSEUM FRAN WINANT EXTENDED SENSIBILITIES HOMOSEXUAL PRESENCE IN CONTEMPORARY ART CHARLEY BROWN HARMONY HAMMOND SCOTT BURTON JOHN HENNINGER CRAIG CARVER JERRY JANOSCO ARCH CONNELLY LILI LAKICH JANET COOLING LES PETITES BONBONS BETSY DAMON ROSS PAXTON NANCY FRIED JODY PINTO JEDD GARET CARLA TARDI GILBERT & GEORGE FRAN WINANT LE.E GORDON Daniel J. Cameron Guest Curator The New Museum EXTENDED SENSIBILITIES STAFF ACTIVITIES COUNCJT . Robin Dodds Isabel Berley HOMOSEXUAL PRESENCE IN CONTEMPORARY ART Nina Garfinkel Marilyn Butler N Lynn Gumpert Arlene Doft ::;·z17 John Jacobs Elliot Leonard October 16-December 30, 1982 Bonnie Johnson Lola Goldring .H6 Ed Jones Nanette Laitman C:35 Dieter Morris Kearse Dorothy Sahn Maria Reidelbach Laura Skoler Rosemary Ricchio Jock Truman Ned Rifkin Charles A. Schwefel INTERNS Maureen Stewart Konrad Kaletsch Marcia Thcker Thorn Middlebrook GALLERY ATTENDANTS VOLUNTEERS Joanne Brockley Connie Bangs Anne Glusker Bill Black Marcia Landsman Carl Blumberg Sam Robinson Jeanne Breitbart Jennifer Q. Smith Mary Campbell Melissa Wolf Marvin Coats Jody Cremin This exhibition is supported by a grant from the National Endowment for BOARD OF TRUSTEES Joanna Dawe the Arts in Washington, D.C., a Federal Agency, and is made possible in Jack Boulton Mensa Dente part by public funds from the New York State Council on the Arts. Elaine Dannheisser Gary Gale Library of Congress Catalog Number: 82-61279 John Fitting, Jr. -

Cole Porter: the Social Significance of Selected Love Lyrics of the 1930S

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Unisa Institutional Repository Cole Porter: the social significance of selected love lyrics of the 1930s by MARILYN JUNE HOLLOWAY submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the subject of ENGLISH at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR IA RABINOWITZ November 2010 DECLARATION i SUMMARY This dissertation examines selected love lyrics composed during the 1930s by Cole Porter, whose witty and urbane music epitomized the Golden era of American light music. These lyrics present an interesting paradox – a man who longed for his music to be accepted by the American public, yet remained indifferent to the social mores of the time. Porter offered trenchant social commentary aimed at a society restricted by social taboos and cultural conventions. The argument develops systematically through a chronological and contextual study of the influences of people and events on a man and his music. The prosodic intonation and imagistic texture of the lyrics demonstrate an intimate correlation between personality and composition which, in turn, is supported by the biographical content. KEY WORDS: Broadway, Cole Porter, early Hollywood musicals, gays and musicals, innuendo, musical comedy, social taboos, song lyrics, Tin Pan Alley, 1930 film censorship ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I should like to thank Professor Ivan Rabinowitz, my supervisor, who has been both my mentor and an unfailing source of encouragement; Dawie Malan who was so patient in sourcing material from libraries around the world with remarkable fortitude and good humour; Dr Robin Lee who suggested the title of my dissertation; Dr Elspa Hovgaard who provided academic and helpful comment; my husband, Henry Holloway, a musicologist of world renown, who had to share me with another man for three years; and the man himself, Cole Porter, whose lyrics have thrilled, and will continue to thrill, music lovers with their sophistication and wit. -

George Platt Lynes David Zwirner

David Zwirner New York London Hong Kong George Platt Lynes Artist Biography Among the greatest photographers of the twentieth century, George Platt Lynes (1907–1955) developed a uniquely elegant and distinctive style of portraiture alongside innovative investigations of the erotic and formal qualities of the male nude body. Born and raised in New Jersey with his brother Russell, who would go on to become a managing editor at Harper’s Magazine, Lynes entertained literary ambitions in his youth. While at prep school in Massachusetts, where he studied beside future collaborator and New York City Ballet founder Lincoln Kirstein, he began a correspondence with the American writer Gertrude Stein, then living in Paris. Over a series of successive visits to Paris, he met Stein and her partner, Alice B. Toklas, who integrated him into their creative milieu. At their salons, he met such figures as the painter Pavel Tchelitchew, French writer André Gide, and the dancer Isadora Duncan. Accompanying him on many of these transatlantic journeys was a romantically involved couple consisting of writer Glenway Wescott and the publisher and future director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Monroe Wheeler, the latter of whom became Lynes’s lover. During a failed attempt to write a novel and a successful stint as the owner of a bookshop in New Jersey, Lynes began experimenting with a camera in 1929, photographing friends in his creative social circles in New York and Paris. Those early casual experiments would become a serious commitment to the medium. In 1931, he settled in New York, where his ménage à trois continued with Wheeler and Wescott, with all three sharing an apartment, an arrangement that lasted until 1943. -

À La Recherche De La Continuité Territoriale Entre Londres Et Le

183 DuNight-Ferry à Eurostar:à la recherchede la continuitéterritoriale entreLondres et le continent FromNight Ferry to Eurostar: ln searchof the territorialcontinuity betweenLondon and thecontinent Etienne AUPHAN Université de Nancy 2 UFR des Sciences Historiques et Géographiques BP 3397 - 54015 - NANCY - France Résumé : La liaison entre Londres et le continent a fait l'objet, depuis le siècle dernier, et surtout depuis 25 ans, d'une recherche toujours plus poussée de formules se rapprochant de la continuité territoriale . Pour le transport des personnes, se sont ainsi notamment succédés la formule des gares maritimes et des trains-ferries traduisant le triomphe chi couple train-bateau, les car-ferries, consacrant le règne de l'automobile , les aéroglisseurs exprimant l'exigence de vitesse, et enfin le tunnel ferroviaire qui assure une continuité territoriale presque parfaite, mais paradoxalement au profit du rail, instaurant ainsi de nouveaux rapports intermodaux, aux conséquences sans doute encore mal mesurées sur le fonctionnement de l'espace littoral et w système de transport en ·général. Mots-clés France - Royaume-Uni - Tunnel sous la Manche - Transports intermodaux - Continuité territoriale Abstract : The aim of linking London to the continent has, since the last century and above during the last 25 years , been the object of a search for ever more advanced methods getting ever closer to a land link. For the transport of people, a number of methods have succeeded each other : ferry ports and rail-ferries reflected the triumph of the train-boat partnership, the car-ferries manifested the era of the car, hovercraft expressed the need for speed and, finally, the rail tunnel which assures an almost perfect territorial link. -

Autumn 2017 Cover

Volume 1, Issue 2, Autumn 2017 Front cover image: John June, 1749, print, 188 x 137mm, British Museum, London, England, 1850,1109.36. The Journal of Dress History Volume 1, Issue 2, Autumn 2017 Managing Editor Jennifer Daley Editor Alison Fairhurst Published by The Association of Dress Historians [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org i The Journal of Dress History Volume 1, Issue 2, Autumn 2017 ISSN 2515–0995 [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org Copyright © 2017 The Association of Dress Historians Online Computer Library Centre (OCLC) accession number: 988749854 The Association of Dress Historians (ADH) is Registered Charity #1014876 of The Charity Commission for England and Wales. The Association of Dress Historians supports and promotes the advancement of public knowledge and education in the history of dress and textiles. The Journal of Dress History is the academic publication of The Association of Dress Historians through which scholars can articulate original research in a constructive, interdisciplinary, and peer–reviewed environment. The journal is published biannually, every spring and autumn. The Journal of Dress History is copyrighted by the publisher, The Association of Dress Historians, while each published author within the journal holds the copyright to their individual article. The Journal of Dress History is distributed completely free of charge, solely for academic purposes, and not for sale or profit. The Journal of Dress History is published on an Open Access platform distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The editors of the journal encourage the cultivation of ideas for proposals. -

Program Notes by Dr

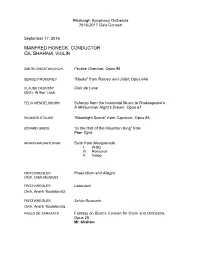

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra 2016-2017 Gala Concert September 17, 2016 MANFRED HONECK, CONDUCTOR GIL SHAHAM, VIOLIN DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH Festive Overture, Opus 96 SERGEI PROKOFIEV “Masks” from Romeo and Juliet, Opus 64a CLAUDE DEBUSSY Clair de Lune Orch. Arthur Luck FELIX MENDELSSOHN Scherzo from the Incidental Music to Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Opus 61 RICHARD STAUSS “Moonlight Scene” from Capriccio, Opus 85 EDVARD GREIG “In the Hall of the Mountain King” from Peer Gynt ARAM KHACHATURIAN Suite from Masquerade I. Waltz IV. Romance V. Galop FRITZ KREISLER Praeludium and Allegro Orch. Clark McAlister FRITZ KREISLER Liebesleid Orch. André Kostelanetz FRITZ KREISLER Schön Rosmarin Orch. André Kostelanetz PABLO DE SARASATE Fantasy on Bizet’s Carmen for Violin and Orchestra, Opus 25 Mr. Shaham Sept. 17, 2016, page 1 PROGRAM NOTES BY DR. RICHARD E. RODDA DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH (1906-1975) Festive Overture, Opus 96 (1954) Among the grand symphonies, concertos, operas and chamber works that Dmitri Shostakovich produced are also many occasional pieces: film scores, tone poems, jingoistic anthems, brief instrumental compositions. Though most of these works are unfamiliar in the West, one — the Festive Overture — has been a favorite since it was written in the autumn of 1954. Shostakovich composed it for a concert on November 7, 1954 commemorating the 37th anniversary of the Russian Revolution, but its jubilant nature suggests it may also have been conceived as an outpouring of relief at the death of Joseph Stalin one year earlier. One critic suggested that the Overture was “a gay picture of streets and squares packed with a young and happy throng.” As its title suggests, the Festive Overture is a brilliant affair, full of fanfare and bursting spirits. -

Teacher Notes on Russian Music and Composers Prokofiev Gave up His Popularity and Wrote Music to Please Stalin. He Wrote Music

Teacher Notes on Russian Music and Composers x Prokofiev gave up his popularity and wrote music to please Stalin. He wrote music to please the government. x Stravinsky is known as the great inventor of Russian music. x The 19th century was a time of great musical achievement in Russia. This was the time period in which “The Five” became known. They were: Rimsky-Korsakov (most influential, 1844-1908) Borodin Mussorgsky Cui Balakirev x Tchaikovsky (1840-’93) was not know as one of “The Five”. x Near the end of the Stalinist Period Prokofiev and Shostakovich produced music so peasants could listen to it as they worked. x During the 17th century, Russian music consisted of sacred vocal music or folk type songs. x Peter the Great liked military music (such as the drums). He liked trumpet music, church bells and simple Polish music. He did not like French or Italian music. Nor did Peter the Great like opera. Notes Compiled by Carol Mohrlock 90 Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky (1882-1971) I gor Stravinsky was born on June 17, 1882, in Oranienbaum, near St. Petersburg, Russia, he died on April 6, 1971, in New York City H e was Russian-born composer particularly renowned for such ballet scores as The Firebird (performed 1910), Petrushka (1911), The Rite of Spring (1913), and Orpheus (1947). The Russian period S travinsky's father, Fyodor Ignatyevich Stravinsky, was a bass singer of great distinction, who had made a successful operatic career for himself, first at Kiev and later in St. Petersburg. Igor was the third of a family of four boys. -

Szymanowski, Karol Maciej (1882-1937) by Douglas Blair Turnbaugh

Szymanowski, Karol Maciej (1882-1937) by Douglas Blair Turnbaugh Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2002, glbtq, Inc. Karol Szymanowski. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Revered as the father of Polish contemporary classical music, Karol Szymanowski unequivocally expresses homoeroticism in his music. He was born at Timoshovska, Ukraine, on October 3, 1882. Although born in Russian territory, Szymanowski was of a noble Polish family. The family estate was a center of musical activity, and, with his father as his teacher, Szymanowski's musical education began at an early age. A masterly pianist, he later studied privately in Warsaw, but was an autodidact in composition. His earliest work, influenced by Chopin and Scriabin, is lyrical, but dominated by sentimental melancholy. In 1905 Szymanowski began to live abroad, as he continued his "self-education." The rich, talented, handsome young aristocrat was an ornament in the stupendous social whirl of pre-World War I Berlin, Leipzig, and Vienna. With his friend Stefan Spiess, he visited Sicily in 1911 and Algiers and Tunis in 1914. Szymanowski, not unlike other European gay artists, such as Baron von Gloeden, Oscar Wilde, and André Gide, found the spectacle of unabashed boy-love in the less inhibited southern climate to be psychologically liberating and, thereby, an inspiration to his art. Szymanowski celebrated his newly liberated sexuality in his music. After the Sicilian visit, the melancholy of his earlier work was vanquished by the joy that would be present throughout the rest of his creative life. Homoeroticism is discernible in much of his music, especially in such works as "Love Songs of Hafiz" and "Third Symphony--Song of the Night, for tenor solo," a setting of a poem by the thirteenth-century Persian poet Rumi. -

ROMAN ROAD PRESS RELEASE PHOTO LONDON Stand G23

ROMAN ROAD PRESS RELEASE PHOTO LONDON Stand G23 Thursday 17 May – Sunday 20 May 2018 Opening Hours: Thursday 17 May: 12 PM – 8 PM Somerset House Friday 18 May: 12 PM – 7.30 PM Strand Saturday 19 May: 12 PM – 7.30 PM London, WC2R 1LA Sunday 20 May: 12 PM – 6.30 PM Exhibited Artists: Antony Cairns, Gita Lenz, Natalia LL, George Platt Lynes, Aaron Siskind, Daisuke Yokota Roman Road is very pleased to be participating in the fourth edition of Photo London, hosted at Somerset House from 17 – 20 May 2018. Featuring both 20th-century and contemporary photographic works, our stand brings together pieces by international artists who have engaged with experimental printing methods and the aesthetics of abstraction. The display considers the definitions of abstract photography, looking at the originality and process of artists who have abstracted subject and composition, or experimented with techniques that manipulate forms and impart new meaning. The stand features experimental works by contemporary artists Antony Cairns and Daisuke Yokota. Employing unlikely supports and radical techniques, Cairns’ work engages deeply with technological developments and he transforms machines and recycled materials into art objects. The display includes selected works from two of his most recent series – E.I. and IBM – through which he presents his images of cities petrified in e-reader screens and printed on tinted IBM computer punch cards. Yokota’s works on the stand are taken from his Matter/Burn Out (2016), a series whereby he documented the process of setting fire to installation prints in a vacant construction site in Xiamen, China. -

Paris Study Abroad Summer Program

Paris Study Abroad Summer Program get ready to delight Thursday May 23rd your taste buds! Rendez-vous at 6:30pm About the restaurant Services Enjoy the large, Chartier is over 100 years old legendary, dining room and still in the very prime of listed as a historical life. The restaurant is dear to heritage. native Parisians, which might help explain why it is just as Watch with delight the beloved by tourists from over servers that are dressed the world. in black vests and white aprons. They are famous In 1896, the Bouillon Chartier for their efficiency. was born out of a very simple Address concept – provide a decent meal at a reasonable price and 7 rue du Faubourg give customers good service in Montmartre order to earn their loyalty. 75009 PARIS Lunch Cruise Discover Paris in a new light. Enjoy a lunch cruise on the Seine River. Thursday June 28th Rendez-vous at noon Over water, rediscover Paris’s most beautiful monuments with a unique perspective from a panoramic boat! Address: Port de Solferino, on the river, in front of the Musée d’Orsay Address Wednesday June 26th 17 rue Jacques Ibert Rendez-vous at 8:30am 75017 Paris Workshop Perfect the quintessential French style with a workshop in chocolate specialties. Learn hands- on techniques and the art of presentation. Restaurant Lunch at the school’s restaurant served by students. HOTEL VISIT LE Tuesday May 28th MEURICE Rendez-vous at 2pm ADDRESS PARISIAN PALACE AFTERNOON TEA 228 rue de Rivoli 75001 Paris In 2011, the hotel received 'palace' status.