William CC Claiborne and the Creation Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Knoll, J. Not on Panel. Rule IV, Part 2, Section 3. Editor's Note: Revised

Editor’s note: Revised Opinion 7/26/00; Original Opinion Released July 6, 2000 SUPREME COURT OF LOUISIANA No. 99-KA-0606 STATE OF LOUISIANA VERSUS MITCHELL SMITH On Appeal from the Criminal District Court for the Parish of Orleans, Honorable Patrick G. Quinlan, Judge c/w No. 99-KA-2015 STATE OF LOUISIANA VERSUS LISA M. GARRETT On Appeal from the Criminal District Court, for the Parish of Orleans, Honorable Frank A. Marullo, Jr. Judge c/w NO. 99-KA-2019 STATE OF LOUISIANA VERSUS MELANIE VARNADO On Appeal from the Criminal District Court, for the Parish of Orleans, Honorable Arthur L. Hunter, Judge NO. 99-KA-2094 STATE OF LOUISIANA VERSUS KELLY A. BARON On Appeal from the Criminal District Court, for the Parish of Orleans, Honorable Calvin Johnson, Judge TRAYLOR, Justice* FACTS/PROCEDURAL HISTORY On September 24, 1995, the alleged victim and Mitchell Smith began talking while consuming *Knoll, J. not on panel. Rule IV, Part 2, Section 3. alcohol at Brewski’s Lounge in Chalmette. After at least one cocktail together, Mr. Smith asked her to accompany him to another bar, and the two left and went to Gabby’s, a bar in New Orleans East. While at Gabby’s, the alleged victim felt sick, apparently from consuming alcohol while taking epilepsy medicine. Although she testified that she told Mr. Smith she wanted to go home, Mr. Smith convinced her to go to a motel with him to “rest.” She claimed she hesitantly agreed after insisting that nothing was going to happen between them. Mr. Smith testified that he asked her to “fool around” and she agreed. -

Llttroduction the Section of Louisiana

area between the two northe111 boundaries \llhich the English had established was in dispute between the new United States and Spain, who again owned the rest of llTTRODUCTION Flo~ida - both East and West - as a result of the lat est Treaty of Paris. This dispute continued until 1798, when the United States waS finally put in The section of Louisiana known today as the pos~ession of the area to the thirty-first parallel "Florida Parishes" -- consisting of the eight (the lower boundary line), which waS re-established parishes of East and West Feliciana, East Baton Rouge, as the northern boundar,y of West Florida. st. Helena, Livingston, Tangipahoa, Washington, and When the United States purchased from France in St. Tammany -- was included in the area known as the 1803 the real estate west of the Mississippi River province of I1Louisiana" claimed by France until 1763· kno"m as the "Louisiana Purchase," the United States Under the terms of the Treaty of Paris which in that mad~ feeble claims on the area of West Florida re year ended the Seven Years War, or the French and maining to Spain. Indian Wax, this territory became English along with Meantime, several abortive attempts at all the territory east of the Mississippi River ex reb~llion against Spain were made within the area. cept the Isle of Orleans*. Even the Spanish province On 23 September 1810 a successful armed revolt of "Florida" (approximately the present state of OCC1.trred, and for a short time the "Republic of Florida) became English at that time. -

Supreme Court of the United States

No. 19-5807 ================================================================================================================ In The Supreme Court of the United States --------------------------------- --------------------------------- THEDRICK EDWARDS, Petitioner, versus DARREL VANNOY, WARDEN, LOUISIANA STATE PENITENTIARY, Respondent. --------------------------------- --------------------------------- On Writ Of Certiorari To The United States Court Of Appeals For The Fifth Circuit --------------------------------- --------------------------------- BRIEF OF LOUISIANA PROFESSORS OF LAW AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER --------------------------------- --------------------------------- HERBERT V. L ARSON, JR. Senior Professor of Practice TULANE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW 6329 Freret Street New Orleans, Louisiana 70115 (504) 865-5839 [email protected] Louisiana Bar No. 8052 Counsel of Record for Amici Curiae ================================================================================================================ COCKLE LEGAL BRIEFS (800) 225-6964 WWW.COCKLELEGALBRIEFS.COM i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ................................. ii INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE ......................... 1 SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT ..................... 2 ARGUMENT ........................................................ 4 I. THE RIGHT TO TRIAL BY JURY IN LOUISIANA – 1804-1861 .......................... 4 II. THE RIGHT TO TRIAL BY JURY IN LOUISIANA – 1868-1880 .......................... 12 III. THE RIGHT TO TRIAL BY JURY IN -

A Medley of Cultures: Louisiana History at the Cabildo

A Medley of Cultures: Louisiana History at the Cabildo Chapter 1 Introduction This book is the result of research conducted for an exhibition on Louisiana history prepared by the Louisiana State Museum and presented within the walls of the historic Spanish Cabildo, constructed in the 1790s. All the words written for the exhibition script would not fit on those walls, however, so these pages augment that text. The exhibition presents a chronological and thematic view of Louisiana history from early contact between American Indians and Europeans through the era of Reconstruction. One of the main themes is the long history of ethnic and racial diversity that shaped Louisiana. Thus, the exhibition—and this book—are heavily social and economic, rather than political, in their subject matter. They incorporate the findings of the "new" social history to examine the everyday lives of "common folk" rather than concentrate solely upon the historical markers of "great white men." In this work I chose a topical, rather than a chronological, approach to Louisiana's history. Each chapter focuses on a particular subject such as recreation and leisure, disease and death, ethnicity and race, or education. In addition, individual chapters look at three major events in Louisiana history: the Battle of New Orleans, the Civil War, and Reconstruction. Organization by topic allows the reader to peruse the entire work or look in depth only at subjects of special interest. For readers interested in learning even more about a particular topic, a list of additional readings follows each chapter. Before we journey into the social and economic past of Louisiana, let us look briefly at the state's political history. -

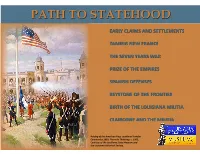

Path to Statehood

PATH TO STATEHOOD EARLY CLAIMS AND SETTLEMENTS TAMING NEW FRANCE THE SEVEN YEARS WAR PRIZE OF THE EMPIRES SPANISH DEFENSES KEYSTONE OF THE FRONTIER BIRTH OF THE LOUISIANA MILITIA CLAIBORNE AND THE MILITIA Raising of the American Flag: Louisiana Transfer Ceremonies,1803, Thure de Thulstrup, c. 1902, Courtesy of the Louisiana State Museum and the Louisiana Historical Society. EARLY CLAIMS 1541 COMPETING CLAIMS Among the early European explorers of North America, Hernando DeSoto claimed all the lands drained by the Mississippi River for Spain in 1541. Spain, however, was not the first naon to colonize the land that would become Louisiana. Nave American tribes in the area, such as the Discovery of the Mississippi by de Soto Natchez, Choctaw, Creek, and Chickasaw, both Hernando de SotoHernando de Soto by William Henry Powell, 1853 resisted and aided the opposing European empires who were systemacally conquering their nave Lands. The alliances oen fell along tradional rivalries. For example, the Creeks allied with the Brish while long term enemies, the Choctaw, aligned 1682 with France. Rene-Robert Cavalier, Sieur de La Salle claimed the Mississippi River basin for France in 1682. It would fall on other Frenchmen to consolidate the claim for the monarchy. Rene-Robert Cavailer, Sieur de La Salle La Salle Colony Map, 1701 TAMING NEW FRANCE . La Louisiane 1699 The Canadian LeMoyne brothers were leaders of French exploraon and selement efforts along the Gulf Coast and up the Mississippi River. Pierre LeMoyne D’Iberville established military outposts and small selements at Biloxi and Mobile, 1699-1701. A temporary fort was created near the mouth of the Mississippi, but Iberville could not find high enough ground to sele a permanent Mississippi River port city. -

The Politics of Gossip in Early Virginia

"SEVERAL UNHANDSOME WORDS": THE POLITICS OF GOSSIP IN EARLY VIRGINIA Christine Eisel A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2012 Committee: Ruth Wallis Herndon, Advisor Timothy Messer-Kruse Graduate Faculty Representative Stephen Ortiz Terri Snyder Tiffany Trimmer © 2012 Christine Eisel All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Ruth Wallis Herndon, Advisor This dissertation demonstrates how women’s gossip in influenced colonial Virginia’s legal and political culture. The scandalous stories reported in women’s gossip form the foundation of this study that examines who gossiped, the content of their gossip, and how their gossip helped shape the colonial legal system. Focusing on the individuals involved and recreating their lives as completely as possible has enabled me to compare distinct county cultures. Reactionary in nature, Virginia lawmakers were influenced by both English cultural values and actual events within their immediate communities. The local county courts responded to women’s gossip in discretionary ways. The more intimate relations and immediate concerns within local communities could trump colonial-level interests. This examination of Accomack and York county court records from the 1630s through 1680, supported through an analysis of various colonial records, family histories, and popular culture, shows that gender and law intersected in the following ways. 1. Status was a central organizing force in the lives of early Virginians. Englishmen punished women who gossiped according to the status of their husbands and to the status of the objects of their gossip. 2. English women used their gossip as a substitute for a formal political voice. -

Cadastral Patterns in Louisiana: a Colonial Legacy

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1978 Cadastral Patterns in Louisiana: a Colonial Legacy. Carolyn Oliver French Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation French, Carolyn Oliver, "Cadastral Patterns in Louisiana: a Colonial Legacy." (1978). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 3201. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/3201 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)” . If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

LOUISIANA PURCHASE New Orleans LOUISIANA

1 The HistoricTHE LOUISIANA PURCHASE New Orleans LOUISIANA Collection THE PURCHASE MUSEUM • RESEARCH CENTER • PUBLISHER The Louisiana Purchase Teacher’s guide: grade levels 7–9 Number of class periods: 3 Copyright © 2015 The Historic New Orleans Collection; copyright © 2015 The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History All rights reserved Copyright © 2015 The Historic New Orleans Collection | www.hnoc.org | copyright © 2015 The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History | www.gilderlehrman.org THE LOUISIANA PURCHASE 2 The Louisiana Purchase Metadata Grade levels 7–9 Number of class periods: 3 What’s Inside: Lesson One....p. 4 Lesson Two....p. 8 Lesson Three....p. 15 Common Core Standards CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.8.1: Cite the textual evidence that most strongly supports an analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text. CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.8.2: Determine a central idea of a text and analyze its development over the course of the text, including its relationship to supporting ideas; provide an objective summary of the text. CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.8.3: Analyze how a text makes connections among and distinctions between individuals, ideas, or events (e.g., through comparisons, analogies, or categories). CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.8.4: Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including figurative, connotative, and technical meanings; analyze the impact of specific word choices on meaning and tone, including analogies or allusions to other texts. CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.8.5: Analyze in detail the structure of a specific paragraph in a text, including the role of particular sentences in developing and refining a key concept. -

Territorial Courts and the Law: Unifying Factors in the Development of American Legal Institutions-Pt.II-Influences Tending to Unify Territorial Law

Michigan Law Review Volume 61 Issue 3 1963 Territorial Courts and the Law: Unifying Factors in the Development of American Legal Institutions-Pt.II-Influences Tending to Unify Territorial Law William Wirt Blume University of Michigan Law School Elizabeth Gaspar Brown University of Michigan Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Common Law Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, Legal History Commons, Legislation Commons, Rule of Law Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons Recommended Citation William W. Blume & Elizabeth G. Brown, Territorial Courts and the Law: Unifying Factors in the Development of American Legal Institutions-Pt.II-Influences endingT to Unify Territorial Law, 61 MICH. L. REV. 467 (1963). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol61/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TERRITORIAL COURTS AND LAW UNIFYING FACTORS IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF AMERICAN LEGAL INSTITUTIONS William Wirt Blume* and Elizabeth Gaspar Brown** Part II. INFLUENCES TENDING To UNIFY TERRITORIAL LAWf ITH the exception of Kentucky, Vermont, Texas, California, W and West Virginia, all parts of continental United States south and west of the present boundaries of the original states came under colonial rule, and were governed from the national capital through territorial governments for varying periods of time. -

Surveys in Early American Louisiana: 1804-1806 Barthelemy Lafon

Surveys in Early American Louisiana: 1804-1806 Barthelemy Lafon VOLUME II Edited by Jay Edwards Translated by Ina Fandrich PROPERTY OF THE MASONIC GRAND LODGE, ALEXANDRIA, LOUISIANA 634 Royal Street, New Orleans, designed by Barthelemy Lafon ca. 1795. A Painting by Boyd Cruise Surveys in Early American Louisiana: Barthelemy Lafon Survey Book No. 3, 1804 – 1806. Translated from the Original French VOLUME II. Written and Edited by Jay Edwards, Written and Translated by Ina Fandrich A REPORT TO: THE LOUISIANA DIVISION OF HISTORIC PRESERVATION AND THE MASONIC GRAND LODGE, ALEXANDRIA, LOUISIANA July 26, 2018. ii INDEX Contents: Pages: Chapter I. A Biography of Barthelemy Lafon. 1 - 19 Chapter 2.1. New Orleans Urban Landscapes and Their Architecture on the Eve of Americanization… 21 – 110 Chapter 2.2. Summary of Barthelemy Lafon’s Architectural Contributions 111 - 115 Chapter 3. Translation Keys and Commentary 117 - 128 Chapter 4. English Language Translations of Lafon’s Surveys Translated, Nos. 1 – 181 1 (129) – 300.2 (376) iii NOTIFICATIONS The historic manuscript which is translated in this volume is the private property of the Library- Museum of the Masonic Grand Lodge of the State of Louisiana, Free & Accepted Masons. They are located in Alexandria, Louisiana. No portion of this volume may be reproduced or distributed without the prior permission of the Grand Secretary of the Grand Lodge. A form must be filled out and returned to the Archivist for his written signature before any reproduction may be made. The English language translations in this volume and the “Translator’s Keys and Commentary” are the work and the property of Dr. -

The United States

Bulletin No. 226 . Series F, Geography, 37 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES V. WALCOTT, DIRECTOR BOUNDARIES OF THE UNITED STATES AND OF THE SEVERAL STATES AND TERRITORIES WITH AN OUTLINE OF THE HISTORY OF ALL IMPORTANT CHANGES OF TERRITORY (THIRD EDITION) BY HENRY G-ANNETT WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1904 CONTENTS. LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL .................................... ............. 7 CHAPTER I. Boundaries of the United States, and additions to its territory .. 9 Boundaries of the United States....................................... 9 Provisional treaty Avith Great Britain...........................'... 9 Treaty with Spain of 1798......................................... 10 Definitive treaty with Great Britain................................ 10 Treaty of London, 1794 ........................................... 10 Treaty of Ghent................................................... 11 Arbitration by King of the Netherlands............................ 16 Treaty with Grreat Britain, 1842 ................................... 17 Webster-Ash burton treaty with Great Britain, 1846................. 19 Additions to the territory of the United States ......................... 19 Louisiana purchase................................................. 19 Florida purchase................................................... 22 Texas accession .............................I.................... 23 First Mexican cession....... ...................................... 23 Gadsden purchase............................................... -

Maryland's First Ten Years

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 5-18-2007 Competition and Conflict: Maryland's First Ten Years Matthew Edwards University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Edwards, Matthew, "Competition and Conflict: Maryland's First Ten Years" (2007). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 513. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/513 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Competition and Conflict: Maryland’s First Ten Years A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History by Matthew C. Edwards B.A. East Central University, 2004 May 2007 Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................