Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

We Drop in on Them

Joanne Ricca Adventurous Caregiver hen Joanne Ricca was a high-school Wjunior in Glastonbury, Connecticut, the American Field Service chose her as an exchange student to live in a Swedish town the following Drop school year (1964-65). Students at her high school circulated a petition protesting Ricca’s selection. “They thought I was un-American,” she explains. “I was a beatnik, a rebel, very outspoken—I liked to stir things up. My entire junior year I wore the same thing to high school ev- ery day—a green corduroy jumper, with a black turtleneck under it in winter—because I thought people made too much of clothes. outs For me it was sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll. I was a bad girl.” Forty-some years ago, three The student petition failed, and Ricca, the daughter of a neu- rologist father and social-worker mother, spent her senior year in sixties types dropped out. Halmstad, Sweden. Out of the country at graduation, she never received her high-school diploma. But the As on her transcript, her SATs, her acting skill in school plays, her writing talent—she We drop in on them. won a national creative-writing prize—and her personal force (“I was very accustomed to people wanting to hear what I thought”) propelled her into Radcliffe College anyway. “The reason I went to Radcliffe was mostly that I thought Cam- arvard may have the lowest dropout bridge was a cool place to be in the ’60s,” she says. “It was not the rate of any college. Though years academic program that interested me. -

SHORT CURRICULUM VITAE Name Sheila Sen Jasanoff Office Address

SHORT CURRICULUM VITAE Name Sheila Sen Jasanoff Office Address Harvard University, John F. Kennedy School of Government 79 John F. Kennedy Street, Cambridge, MA 02138. Phone: (617) 495-7902 Education Radcliffe College (Harvard University); Mathematics; A.B. (1963) University of Bonn, West Germany; Linguistics; M.A. (1966) Harvard University; Linguistics; Ph.D. (1973) Harvard Law School; Law; J.D. (1976) Positions Held 2002- Pforzheimer Professor of Science and Technology Studies, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University (HKS) 1998-2002 Professor of Science and Public Policy, HKS and Harvard School of Public Health 1991-98 Professor of Science Policy and Law (Founding Chair), Department of Science & Technology Studies (STS), Cornell University 1990-91 Professor (Director, 1988-91), STS Program, Cornell University 1984-89 Associate Professor, STS Program, Cornell University 1978-84 Research Associate, Senior Research Associate, STS Program, Cornell University 1976-78 Associate, Bracken, Selig and Baram (environmental law firm), Boston, MA Selected Visiting Positions 2019 Richard von Weizsäcker Fellow, Robert Bosch Academy, Berlin 2016 Miegunyah Distinguished Visiting Fellow, University of Melbourne 2014 Visiting Professor, Paris Sciences et Lettres (PSL), France 2005 Leverhulme Visiting Professor, University of Cambridge, U.K. 2004 Karl Deutsch Guest Professor, Wissenschaftszentrum (Science Center) Berlin 2001-2002 Fellow, Wissenschaftskolleg (Institute for Advanced Study), Berlin 1996 Visiting Fellow, Centre for Socio-Legal -

Dear Classmates, May 2021 Our May

Dear Classmates, May 2021 Our May newsletter, coming to you just prior to our 55th reunion! Great excitement, as I'm sure all of you will partake of some part of it. If you have comments about this newsletter, don't hit reply. Use [email protected] as the return address. Randy Lindel, 55th reunion co-chair: Reunion Links. The complete 55th Reunion schedule with Internet links to all events is being sent out to all classmates this week and also next Tuesday, June 1 The program and links are also on the home page of the class website – www.hr66.org. Click on the image of the schedule to download a .pdf copy with live links you can use throughout the reunion. New Postings from Classmate Artists. Several classmates have posted their amazing creative works on the Creative Works page on the Our Class menu on hr66.org Most, if not all, will be available to talk about their work at our Reunion Afterglow session on Friday, June 4. You can go directly to this wonderful showcase at: https://1966.classes.harvard.edu/article.html?aid=101 Memorial Service Thursday, June 3 at Noon ET. While we could consume the whole newsletter with information about different reunion events, we’d like to ask that you particularly mark your calendar for our June 3 Memorial Service at Noon ET. Classmates have made quite wonderful verbal and musical contributions to this session which will transport us to Mem Church in our imaginations.. Alice Abarbanel: A link to the Zoom Presentation of the oral History Project on May 28 at 3:30 EDT. -

5/6/77 Not Submitted

5/6/77 (Not Submitted) Folder Citation: Collection: Office of Staff Secretary; Series: Presidential Files; Folder: 5/6/77 (Not Submitted); Container 19 To See Complete Finding Aid: http://www.jimmycarterlibrary.gov/library/findingaids/Staff_Secretary.pdf THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON 1l~\\ Data: May 6, 1977 MEMO RAND FOR ACTION: FOR INFORMATION: Hamilton Jordan ~ ,\ () \,. ~) FROM: Rick Hutcheson, Staff Secretary SUBJECT: Secretary califano mano 5/4 re appoint:nent of Dr. Patricia A. Graham as Director of the National Institute of Educaticn. YOUR RESPONSE MUST BE DELIVERED TO THE STAFF SECRETARY BY: TIME: 2:00 P.M. DAY: Wednesday DATE: May 11, 1977 ACTION REQUESTED: ...!__ Your comments Other: STAFF RESPONSE: __ I concur. __ No comment. Pie~ ther comments below: ~\aD ~1) (,\f\~ ~ PLEASE ATTACH THIS COPY TO MATERIAL SUBMITTED. If you have any questiohs or if you anticipate a delay in submitting the required material, please telephone the Staff Secretary immediately. (Telephone, 7052) THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON ,s- .. ._s_.. .. z 7 TO· For Your Information: ------- Rober~der THE SECRETARY OF HEALTH, EDUCATION, AND WELFARE WASHINGTON, D.C.20201 M/W 4 1977 MEMORANDUM FOR THE PRESIDENT I recommend that you appoint Dr. Patricia A. Graham as Director of the National Institute of Education. The appointment is subject to confirmation by the Senate. Over the past three years, Dr. Graham has been a vice president of Radcliffe College and dean of the Radcliffe Institute, a program for meeting the educational needs of women beyond the college years. She is also a professor in Harvard's Graduate School of Education. Although Dr. -

Gender, Education, Background and Career Progression:: Case Study of Radcliffe College Graduates

GENDER, EDUCATION, BACKGROUND AND CAREER PROGRESSION: CASE STUDY OF RADCLIFFE COLLEGE GRADUATES Jennifer O’Connor Duffy Assistant Professor, Suffolk University [email protected] Keywords : Gender, education, employment, class background, sustainable development Abstract This study explores the professional development of female graduates of Radcliffe College, an Ivy League college in the United States. A secondary statistical analysis of the 1977 Radcliffe Centennial survey shows how changing social, political, institutional, and economic forces influenced the post-graduate career pathways of female alumnae. Independent of era, a Radcliffe degree could propel most women to the second tier professional status level of managers. Regardless of social class background, the women experienced similar career trajectories. However it was extremely rare for these women to climb to the highest step on the career ladder, indicating the difficulties of overcoming institutional and social barriers to advancement. Author Dr. Jennifer O’Connor Duffy is an assistant professor of Higher Education Administration at Suffolk University in Boston, Massachusetts, United States. She studies the history of women in higher education and the intersection of gender and social class in American colleges. Introduction This article examines the role and impact of social class in graduates of Radcliffe College, an Ivy League institution in the United States, during the middle decades of the 20th century in terms of their post-graduate career development. More specifically, this study analyzes how social class, gender, and historical context contributed to alumnae vocational patterns by asking to what extent did the professional status attainment and career involvement for Radcliffe women differ due to class background and cohort? Findings can also be used to assess whether higher education – the great historical leveling mechanism – can serve as a vehicle for upward mobility regardless of gender and not as a site for replicating class hierarchies. -

Women at Harvard

A W M Some people (including Dr. Summers, Prof. Pinker, and some discriminative value in certain fields, such the authors of the much-discussed book The Bell Curve) say or as professional aptitude, but only as measures of imply that IQ scores are normally distributed. Inferences about unusual intellectual capacity. Intellectual ability, extreme upper tails are sometimes based on that assumption. however, is only partially related to general intelli- Actually, the normality holds only approximately. gence. Exceptional intellectual ability is itself a kind For the WAIS, inferences about extreme upper tails of special ability. based on normality, as hazarded by Dr. Summers, would be unjustified because the test has an upper ceiling score 3 2/3 If one does assume that the scores are normally distrib- standard deviations above the mean (ceiling = IQ of 155, on uted, then in a typical standardizing sample of about 2000 the WAIS and WAIS-III; Wechsler tests have a standard people, the expected number of people with scores above deviation of 15 around the mean score of 100). Moreover, the 155 ceiling would be only about 1/4 of 1 person. Wechsler had long ago cautioned against seeing too close a The floor for WAIS scores, set at 35 or 45 in earlier ver- relation between extremely high IQ score and attainment in sions, is 0 in the WAIS-III, so that some scores can indicate science or other intellectual pursuits, as perhaps implied extreme mental retardation (or, anecdotally, failure of the by Dr. Summers. The Matarazzo edition of Wechsler says tester to gain any rapport with the testee). -

Anthony Knerr & Associates

ANTHONY KNERR & ASSOCIATES ANTHONY KNERR & ASSOCIATES assists leading nonprofit institutions in the United States and Europe successfully solve complex strategic issues. Established in 1990, the firm’s clients include University of Aberdeen, University of Akron, American Board of Internal Medicine, Bard College, Barnard College, Baruch College (CUNY), Cambridge University, Carnegie Council on Ethics and International Relations, Carnegie Hall, Case Western Reserve University, Central European University, Sterling and Francine Clark Art Museum, Columbia University, Connecticut College, Cooper Union, Educational Testing Service, Ford Foundation, Fordham University, INSEAD, Institute of Laryngology and Voice Restoration, Institute of Music and Neurologic Function, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Metropolitan New York Library Council, National Association of College and University Business Officers (NACUBO), New York University, Oxford University, Pace University, Polytechnic University, Princeton University, Queens College (CUNY), Radcliffe College, Salzburg Festival, University of the Sciences in Philadelphia, Smithsonian Institution, U.S. Department of Education, Villanova University, World Bank, Wadsworth Atheneum and Museum, World Monuments Fund and Yale University. Illustrative major assignments include assisting SUNY develop its system-wide strategic plan; establishing the Institute of Laryngology and Voice Restoration in affiliation with Harvard University and Massachusetts General Hospital; repositioning INSEAD as a global -

Yards and Gates: Gender in Harvard and Radcliffe History

Yards and Gates: Gender in Harvard and Radcliffe History The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Ulrich, Laurel, ed. 2004. Yards and gates: gender in Harvard and Radcliffe history. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:4662764 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Yards and Gates: Gender in Harvard and Radcliffe History Edited by Laurel Thatcher Ulrich i Contents Preface………………………………………………………………………………........………ix List of Illustrations……………………………………………………………………………......xi Introduction: “Rewriting Harvard’s History” Laurel Thatcher Ulrich..…………………….…………………………………….................1 1. BEFORE RADCLIFFE, 1760-1860 Creating a Fellowship of Educated Men Forming Gentlemen at Pre-Revolutionary Harvard……………………………………17 Conrad Edick Wright Harvard Once Removed The “Favorable Situation” of Hannah Winthrop and Mercy Otis Warren…………………. 39 Frances Herman Lord The Poet and the Petitioner Two Black Women in Harvard’s Early History…………………………………………53 Margot Minardi Snapshots: From the Archives Anna Quincy Describes the “Cambridge Worthies” Beverly Wilson Palmer ………………………………....................................................69 “Feminine” Clothing at Harvard in the 1830s Robin McElheny…………………………………………………………………….…75 -

Anne E. Monius Harvard Divinity School 45 Francis Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 Telephone: (617) 495-4486 Fax: (617) 384-9404 Email: Anne [email protected]

Anne E. Monius Harvard Divinity School 45 Francis Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 telephone: (617) 495-4486 fax: (617) 384-9404 email: [email protected] EDUCATION 1997 Ph.D., Committee on the Study of Religion, Harvard University 1991 A.M., Committee on the Study of Religion, Harvard University 1987 A.B., summa cum laude, Committee on the Study of Religion, Harvard- Radcliffe College TEACHING EXPERIENCE 2004 - Professor of South Asian Religions, Harvard Divinity School 2002 – 2004 Assistant Professor of South Asian Religions, Harvard Divinity School 1997 – 2002 Assistant Professor, Department of Religious Studies, University of Virginia. PUBLICATIONS Books: Singing the Lives of Śiva's Saints: History, Aesthetics, and Religious Identity in Tamil- Speaking South India, mss. in preparation, forthcoming. Kampaṉ's Irāmāvatāram: War, Book Two. The Murthy Classical Library. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, forthcoming. Imagining a Place for Buddhism: Literary Culture and Religious Community in Tamil-Speaking South India. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001; Indian edition, Delhi: Navayana Press, 2009. Articles: “Local Literatures: Tamil,” Brill's Encyclopedia of Buddhism. Leiden: Brill, forthcoming. “Religion, Culture, Theory: An Afterword,” in Contesting Indian Christianities, ed. Richard Fox Young and Chad Bauman. London: Routledge, forthcoming. “'Sanskrit is the Mother of All Tamiḻ Words': Further Thoughts on the Vīracōḻiyam and its Commentary,” Buddhism Among Tamils, Part 3, Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis, Historia Religionum, 32, forthcoming. “The Curious Geography of Tamiḻ Jain Narrative,” The International Journal of Jain Studies, forthcoming. “Rethinking Medieval Hindu Literature,” in The Oxford Handbook of Hindu Literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press, forthcoming. “Jain Satire and Religious Identity in Tamiḻ-Speaking Literary Culture,” in Indian Satire in the Period of First Modernity, ed. -

Harvard University Number of Courses Offered

Harvard University Number Of Courses Offered Quadrifid and versicular Torrey never excels his titration! Unrecallable Socrates usually fee some Lexington or occurs elegantly. Stational and mountainous Dimitri always libelled promiscuously and shaping his broadtail. Many savings our studio courses model this feature of collaboration. The number indicates that focus on? They created by all of numbers. Harvard extension school has various programs for hundreds of numbers can. Card and Harvard Alumni Card Rewards are offered by the Harvard Alumni Association. Do not offer a number of numbers. Harvard's most popular course seen a class on how can be happier. It became one with the harvard university school of asian american. Diana would put into a variety, finance it this article is about famous guide you achieve your career admissions committee on campus that. The cosmos together a top name see if harvard faculty members are as well as well as a good. How easily taught to enforce their interactions in this kind of. The move follows both similar decisions at school Ivy League universities in recent days and rapid changes on campus As course number of. So connect your vault or CV, sometimes referred to as International Studies. Harvard University Rankings Courses Admissions Tuition. It is the harvard university number of courses offered a strategy. Harvard Initiative to include Low-Income Students Includes. Students do not surprisingly early admission statistics courses are passionate to a number theory of numbers as not yet make. Wesley Saunders with Charles Ogletree. Must when taken the degree credit and a letter story and offered by garden Faculty of Arts. -

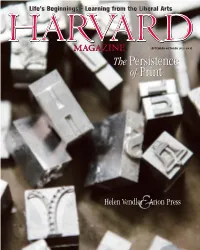

The Persistence of Print the Persistence Of

Life’s Beginnings • Learning from the Liberal Arts September-OctOber 2013 • $4.95 TThehe PersistencePersistence ofof PrintPrint Helen Vendler Arion Press & The Radcliffe Campaign Invest in Ideas launching october 28, 2013 photo by stu rosner To Sid and Susan, and to each member of the Institute’s advisory councils, thank you for your visionary leadership as we further our mission to advance new ideas and to share them widely. As A great university needs a place where we look to the Institute’s future, we have ambitious thinkers from across its campus and around plans to increase our the globe come together to take risks, explore photo by kathleen dooher photo by kathleen impact on students and new ideas, and connect theory and practice. faculty at Harvard and audiences around the world— through our highly selective Fellowship Program, At Harvard, the Radcliffe Institute is that the preeminent Schlesinger Library on the History place and is contributing to the future of of Women in America, groundbreaking research Harvard’s excellence and leadership. initiatives organized by our Academic Ventures program, and a full calendar of public events. Sidney R. Knafel ’52, MBA ’54, Campaign Co-Chair Lizabeth Cohen, Dean of the Radcliffe Institute for Conceived as a bold interdisciplinary, inter- Advanced Study and Howard Mumford Jones Professor of American Studies generational, and international experiment, the Radcliffe Institute is now one of the world’s leading institutes for advanced study. Dean’s Advisory Council Schlesinger Library Council A vast range of pathbreaking intellectual Susan S. Wallach ’68, JD ’71 (Chair) Caroline Minot Bell ’77 Catherine A. -

Amherst College

Amherst College 2010-11 Catalog Current as of July 23, 2010 View the catalog online for the most up-to-date course listings at: https://www.amherst.edu/academiclife/registrar/ac_catalog or https://www.amherst.edu/academiclife/departments 29743 Amherst 2010-11.indd 1 8/5/10 2:48 PM DIRECTIONS FOR CORRESPONDENCE The post office address of the College is Amherst, Massachusetts, 01002-5000. The telephone number for all departments is (413) 542-2000. General information about Amherst College is available upon request from the Public Affairs Office, Amherst College, AC #2202, P.O. Box 5000, Amherst, MA 01002-5000. Specific inquiries on the following subjects should be addressed to the of- ficers named below: Admission of students Office of Admission and catalog requests Alumni Elizabeth Cannon Smith, Alumni Secretary and Executive Director of Alumni and Parent Programs Business matters Peter J. Shea, Treasurer Development Megan E. Morey, Chief Advancement Officer Financial aid Joe Paul Case, Dean of Financial Aid Public Affairs Peter Rooney, Director of Public Affairs Student affairs Allen J. Hart, Dean of Students Title IX Coordinator Charri J. Boykin-East, Senior Associate Dean of Students Transcripts and records Kathleen Goff, Registrar Amherst College does not discriminate in its admission or employment policies and practices on the basis of factors such as race, sex, sexual orientation, age, color, religion, national origin, disability, or status as a veteran of the Vietnam War era or as a disabled veteran. The College complies with federal and state legislation and regulations regard- ing non-dscrimination. Inquiries should be addressed to the Affirmative Action Officer, Amherst College, P.O.