Brewster F2A2 Buffalo 44” Wingspan (1.10M)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Suomen Ilmailuhistoriallinen Lehti

Sivu 1 Suomen Ilmailuhistoriallinen Lehti Artikkeliluettelo n:ot 1/1994 - 3/2018 Koostanut ja sisältökuvaukset laatinut H Paronen Lehden Alkava Kirjoittaja Artikkelin otsikko Pääsisältö 3-taho- numero sivu nr. piirus- tuksia 1994 1 2 Manninen P BZ-35 Ilmavoimien polttoaineauto BZ-35 tankkausauto on 1994 1 3 Manninen P Pääkirjoitus 1994 1 4 Manninen P Hurricane, venäläiset hävittäjät Sotasaaliskoneet Suomessa 1 1994 1 8 Manninen P Hawker Hurricane Mk. IIA ja IIB Kolmitahopiirros on 1994 1 14 Valtonen H In Memoriam Erkki Jaakkola Henkilöhistoria 1994 1 14 Erkki Jaakkolan albumista Fokker-koneita sodan jälkeen 1994 1 16 Manninen P Talvinaamiovärin keitto-ohje Kolmitahopiirros ja maaliohje on 1994 2 2 Kuva-albumi: Neljä kuvaa sodan jälkeen Erkki Jaakkolan kokoelma / K-SIM 1994 2 3 Manninen P Pääkirjoitus 1994 2 4 Valtonen H JABO/JG5 ja 4.&1./SG5 Petsamon Hävittäjäpommittajalentueen toiminta hävittäjäpommittajalentue (FW 190 A-2 ja A-3) 14.(JABO)/JG5, sekä 4. ja 1./SG5 Petsamossa 31.1.43-30.6.44 1994 2 9 LeR 3:n laivuetunnukset Harakka- ja ilves-tunnusten kesällä 1944 historiaa 1994 2 10 Ritaranta E Suomalainen taitolento 75 vuotta Henkilöhistoria Gunnar Holmqvistin lentäjänura 1994 2 12 Aviatsija Dalnego Deistvija Neuvostoliiton kaukotoiminta- ilmavoimat 1994 2 15 Risut ja ruusut 1994 2 15 Picture History of World War II Kirja-arvostelu American Aircraft Production. Kirj. Joshua Stoff 1994 2 16 Manninen P Junkers Ju 88 A-4 Profiilipiirrokset on 1994 3 2 Ilmavoimat Suursaaren operaatiossa Kuvia s. 4/nr. 2/94 alkavaan artikkeliin 1994 3 3 Manninen P Pääkirjoitus 1994 3 4 Stenman K Suursaari, Suursaaren valtauksen ilmahistoria, Ilmasotatoimet 20.3.-28.3.1942 osallistuneet ohjaajat ja koneet. -

The Evolution & Impact of US Aircraft In

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Honors Theses, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Honors Program Fall 10-2019 Take Off to Superiority: The Evolution & Impact of U.S. Aircraft in War Lane Weidner University of Nebraska - Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/honorstheses Part of the Aviation Commons, and the Military History Commons Weidner, Lane, "Take Off to Superiority: The Evolution & Impact of U.S. Aircraft in War" (2019). Honors Theses, University of Nebraska-Lincoln. 184. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/honorstheses/184 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses, University of Nebraska-Lincoln by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. TAKE OFF TO SUPERIORITY: THE EVOLUTION & IMPACT OF U.S. AIRCRAFT IN WAR An Undergraduate Honors Thesis Submitted in Partial fulfillment of University Honors Program Requirements University of Nebraska-Lincoln by Lane M. Weidner, Bachelor of Science Major: Mathematics Minor: Aerospace Studies College of Arts & Sciences Oct 24, 2019 Faculty Mentor: USAF Captain Nicole Beebe B.S. Social Psychology M.Ed. Human Resources, E-Learning ii Abstract Military aviation has become a staple in the way wars are fought, and ultimately, won. This research paper takes a look at the ways that aviation has evolved and impacted wars across the U.S. history timeline. With a brief introduction of early flight and the modern concept of an aircraft, this article then delves into World Wars I and II, along with the Cold, Korean, Vietnam, and Gulf Wars. -

ENGINES KEY 1 1St Column: Number of Engines / Manufacturer

ENGINE GUIDE – World War II PISTON ENGINES KEY 1 1st Column: Number of engines / manufacturer. 2nd Column: Engine name / engine designation + (civil designation). 3rd Column: Maximum power output range across aircraft production run. 4th Column: Configuration & number of cylinders / cooling method / extra notes. KEY 2 P&W: Pratt & Whitney. T.C.: Turbo Compound. T.S.C.: Turbo-Supercharger. W.I.: Water Injection. Grasshopper Series L-2, L-3, L-4, NE, L-8 Production 1 / Continental O-170 65hp Opposed 4 / Air L-2, L-3, L-4 Impressments 1 / Continental O-170 65hp Opposed 4 / Air 1 / Continental A75-9 (civil) 75hp Opposed 4 / Air 1 / Franklin O-150 65hp Opposed 4 / Air 1 / Franklin O-175 65hp Opposed 4 / Air 1 / Lycoming O-145 65hp Opposed 4 / Air 1 / Lycoming GO-145 100hp Opposed 4 / Air L-16 Production 1 / Continental O-190 85hp Opposed 4 / Air 1 / Continental O-205 90hp Opposed 4 / Air HE Production 1 / Lycoming O-235 104hp Opposed 4 / Air L-14, L-21 Production 1 / Lycoming O-290 125hp – 135hp Opposed 4 / Air L-18 Production 1 / Continental O-205 90hp Opposed 4 / Air L-6 Production 1 / Franklin O-200 100hp In-line 4 / Air Beechcraft C-45 Expeditor Civil Model 18 Production (pre WW2) 2 / Wright J3 Whirlwind R-760 320hp Radial 7 / Air 2 / Jacobs L-5 R-830 285hp Radial 7 / Air 2 / Jacobs L-6 R-915 330hp Radial 7 / Air 2 / Wright J6 Whirlwind R-975 365hp Radial 9 / Air 2 / P&W Wasp Junior R-985 450hp Radial 9 / Air C-45, AT-7, AT-11, F-2, JRB, SNB Production C-45G, TC-45G, C-45H, AT-11A, JRB-6, SNB-5 Conversions 2 / P&W Wasp Junior R-985 450hp Radial 9 / Air Civil Model 18 Production (post WW2) 2 / Continental R-9A* 525hp Radial 9 / Air 2 / P&W Wasp Junior R-985 450hp Radial 9 / Air * developed from the Wright Whirlwind R-975. -

Your Continued Donations Keep Wikipedia Running

Brewster Buffalo F2A "Buffalo" F2A-1 of US Navy squadron VF-3. Type Single seat carrier-based fighter Manufacturer Brewster Aeronautical Corporation Designed by Dayton Brown and R.D. MacCart Maiden flight 2 December 1937 Introduced April 1939 Retired 1948 Primary users United States Navy Royal Air Force Produced 1938-1941 Number built 509 The Brewster Buffalo, or Brewster F2A, was an American fighter plane which saw limited service with both Allied and Finnish air forces during World War II. The F2A was the first monoplane fighter aircraft used by the United States Navy. It was derided by some American servicemen as "flying coffins"[1] due to a reputation for poor construction and marginal performance. Despite this, with the Ilmavoimat (Finnish Air Force), the F2A proved a potent weapon versus the Red Air Force. Design and development In the 1930s, the Brewster Aeronautical Corporation was a relatively new manufacturer which had wanted to enter the aviation market. In 1934 they secured a Navy contract for an aircraft of original Brewster design, the XSBA-1 scout bomber. The XSBA was rather innovative for its time, and was an all-metal monoplane featuring a retractable landing gear and an enclosed bomb bay. New business for Brewster came in the form of a 1935 US Navy requirement for an aircraft carrier- based fighter intended to replace the Grumman F3F biplane. Two aircraft designs were considered: the Brewster Model 139 and the Grumman XF4F-1 which was still a "classic" biplane. The Model 139 incorporated sophisticated features for the time: a monoplane configuration, wing flaps, arresting gear, retractable landing gear and an enclosed cockpit. -

WWII Aviation Crossword Puzzle Answer Key Across: 1

educator guide 2.0 Cradle of Aviation Museum Charles Lindbergh Blvd., Garden City, NY Dear Educator, We hope this guide will enhance your field trip and extend the visit beyond the museum into the classroom. Within each gallery section there are activities and material for you to use before, during and after your visit. You will discover exciting ways to fulfill core curriculum standards through aviation and space exploration. The Cradle of Aviation Museum’s mission is “to inspire future generations through the exploration of air and space technologies.” To fulfill this goal, we are dedicated to simultaneously educating and entertaining through the accurate interpretation of the collection and the exhibitions. Programs developed for school groups and the public focus on everyone’s universal appreciation for flight. Whether an individual has a passion for flying or is attracted to the crafts that make human flight possible, he/she will find a lasting connection here at the Cradle of Aviation Museum. We express our appreciation to all educators who use this guide to make the most of our services and to the New York State Council on the Arts for making this teacher guide possible. Sincerely, The Cradle of Aviation Museum staff Special thanks to the Teacher Guide content contributors: J. Thomas Gwynne; Juliann Gaydos Muller; Rod Leonhard; Joshua Stoff; Shari Abelson; William J. Quinn; Robert H. Muller; Carol Froehlig; Richard Santer; Jennifer Baxmeyer; Robert Tramantano; Fred Truebig and Al Grillo. About the Cradle The 150,000-square-foot Cradle of Aviation Museum is a nonprofit educational corporation in partnership with the County of Nassau. -

Alvin York the Most Decorated Pacifist of World War I

Military Despatches Vol 11 May 2018 Ten military blunders of WWII Ten military mistakes that proved costly Under three flags The man who fought for three different nations Head-to-Head World War II fighter aces Battlefield The Battle of Spion Kop The Boer Commandos A citizen army that was forged in battle For the military enthusiast Military Despatches May 2018 What’s in this month’s edition Feature Articles 6 Top Ten military blunders of World War II Click on any video below to view Ten military operations of World War II that had a major impact on the final outcome of the war. How much do you know about movie theme 16 Under three flags songs? Take our quiz Some men have fought in three different wars, but rarely have they fought for three different countries. and find out. This was one such man. Page 6 20 Rank Structure - WWII German Military Hipe’s Wouter de The old South African Over the next few months we will be running a se- Goede interviews former Defence Force used ries of articles looking at the rank structure of vari- 28’s gang boss David a mixture of English, ous armed forces. This month we look at the German Williams. Afrikaans, slang and Military in World War II. techno-speak that few 24 A matter of survival outside the military Over the next few months we will be running a series could hope to under- of articles looking at survival, something that has al- stand. Some of the terms ways been important for those in the military. -

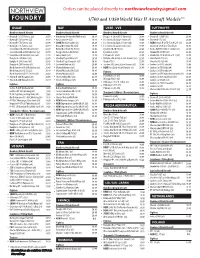

Northview Foundry Catalog A

NORTHVIEW Orders can be placed directly to: [email protected] FOUNDRY 1/700 and 1/350 World War II Aircraft Models** USAAF RAF USSR - VVS LUFTWAFFE Bombers/Attack Aircraft Bombers/Attack Aircraft Bombers/Attack Aircraft Bombers/Attack Aircraft * Boeing B-17C/D Fortress (x2) 20.99 * Armstrong Whitworth Whitley (x3) 20.99 Douglas A-20 w/MV-3 Turret (x3) 20.49 * Dornier D-17M/P (x3) 20.49 * Boeing B-17E Fortress (x2) 20.99 * Avro Lancaster (x2) 20.99 * Il-2 Sturmovik Single-Seater (x4) 19.49 * Dornier D-17Z (x3) 20.49 * Boeing B-17F Fortress (x2) 20.99 * SOON Bristol Beaufort (x3) 20.49 * Il-2 Sturmovik Early 2-Seater (x4) 19.49 * NEW Dornier D-217E-5 w/Hs 293 (x3) 20.49 * Boeing B-17G Fortress (x2) 20.99 Bristol Blenheim Mk.I (x3) 19.49 * Il-2 Sturmovik Late2-Seater (x4) 19.49 Dornier D-217K-2 w/Fritz X (x3) 20.49 Consolidated B-24D Liberator (x2) 20.99 Bristol Blenheim Mk.IV (x3) 19.49 Ilyushin DB-3B/3T (x3) 20.49 * Focke-Wulf Fw 200C-4 Condor (x2) 20.99 ConsolidatedB-24 H/J Liberator (x2) 20.99 Douglas Boston Mk.III (x3) 20.49 Ilyushin IL-4 (x3) 20.49 Heinkel He 111E/F (x3) 20.49 * Consolidated B-32 Dominator (x2) 22.99 * Fairey Battle (x3) 19.49 Petlyakov Pe-2(x3) 20.49 * Heinkel He 111H-20/22 w/V-1 (x3) 20.49 Douglas A-20B Havoc (x3) 20.49 * Handley Page Halifax (x2) 20.99 * Petlyakov Pe-8 Early & Late Variants (x2) 22.99 * Henschel Hs 123 (x4) 19.49 Douglas A-20G Havoc (x3) 20.49 * Handley Page Hampden (x3) 20.49 Tupolev TB-3 22.99 Henschel Hs 129 (x4) 19.49 Douglas A-26B Invader (x3) 20.49 * Lockheed Hudson (x3) 20.49 * Tupolev -

Industry Structure, Innovation, and Competition in the U.S

The U.S. Combat Aircraft Industry 1909-2000 Structure Competition Innovation Mark Lorell Prepared for the Office of the Secretary of Defense R NATIONAL DEFENSE RESEARCH INSTITUTE Approved for public release; distribution unlimited The research described in this report was sponsored by the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD). The research was conducted in RAND’s National Defense Research Institute, a federally funded research and development center supported by the OSD, the Joint Staff, the unified commands, and the defense agencies under Contract DASW01-01-C-0004. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lorell, Mark A., 1947- The U.S. combat aircraft industry, 1909–2000 : structure, competition, innovation / Mark A. Lorell. p. cm. “MR-1696.” ISBN 0-8330-3366-2 (pbk.) 1. Aircraft industry—United States—History. 2. Aircraft industry—United States—Military aspects—History. 3. Fighter planes—United States—History. I.Title. HD9711.U6L67 2003 338.4'7623746'09730904—dc21 2003008114 RAND is a nonprofit institution that helps improve policy and decisionmaking through research and analysis. RAND® is a registered trademark. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions or policies of its research sponsors. Cover design by Peter Soriano © Copyright 2003 RAND All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from RAND. Published 2003 by RAND 1700 Main Street, P.O. Box 2138, Santa Monica, CA 90407-2138 1200 South Hayes Street, Arlington, VA 22202-5050 201 North Craig Street, Suite 202, Pittsburgh, PA 15213-1516 RAND URL: http://www.rand.org/ To order RAND documents or to obtain additional information, contact Distribution Services: Telephone: (310) 451-7002; Fax: (310) 451-6915; Email: [email protected] PREFACE Congress has expressed concerns about three areas of the U.S. -

Brewster F2a Buffalo

BREWSTER F2A BUFFALO BUFFALO SERVICE Manufacturer: Brewster Aeronautical Corp., Long Island City, New York, USA Models: B-139, B-239, B-339 Designation: F2A Name: Buffalo First official flight: XF2A-1 02/12/1937 Factory production period: 1936 – 1941 Primary service period: 1939 – 1942 Last official flight: F2A-2 10/1944 BUFFALO VARIANTS 1937 Model B-139 XF2A-1 1 Total: 001 1939 Model B-239 F2A-1 11 1939 Model B-239 Model B-239 44 Total: 055 1940 Model B-339 F2A-2 43 1940 Model B-339B Model B-339B 40 1940 Model B-339C/D Model B-339C / D 72 1941 Model B-339E Buffalo Mk. I 170 Total: 325 1941 Model B-339-23 F2A-3 108 1941 Model B-339-23 Model B-339-23 20 Total: 128 Total: 509 BUFFALO PRODUCTION XF2A-1 Prototype single engined, USN carrier-borne fighter, fuselage later redesigned. produced 1936 – 1937 Brewster Long Island, New York (A) BuNo. 0451 - 1 Total: 001 F2A-1 As XF2A-1, revised fuselage, fuel capacity 2 guns. 8 later upgraded to F2A-2. produced 1938 – 1939 Brewster Long Island, New York (A) BuNo. 1386 / 1396 - 11 Total: 011 Model B-239 As F2A-1, export version for Finland, carrier equipment removed. produced 1939 – 1940 Brewster Long Island, New York (Finland) BW-351 / BW-394 - 44 Total: 044 F2A-2 As XF2A-2, 4 guns, minor changes. produced 1940 Brewster Newark, New Jersey (A) BuNo. 1397 / 1439 - 43 Total: 043 Model B-339B As F2A-2, export version for Belgium, carrier equipment removed. -

Aircraft Design of Wwii : a Sketchbook Pdf, Epub, Ebook

AIRCRAFT DESIGN OF WWII : A SKETCHBOOK PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Lockheed Aircraft Corporation | 144 pages | 31 Mar 2017 | Dover Publications Inc. | 9780486814209 | English | New York, United States Aircraft Design of WWII : A Sketchbook PDF Book Salmson Cricri. It was far superior to early American aircraft in the Pacific theater, and at one stage had a kill ratio of 12 to 1. It basically lets you analyze aircraft design based on chosen model and parameters. From escorting bombers over Germany to ground attack missions, the Jug could do it all. ADS is my favorite aircraft designer for Windows. Heinkel HD You can check its help manual to figure out its features elaborately. By clicking "Sign Up" you are agreeing to our privacy policy and confirming that you are 13 years old or over. By using our services, you agree to our use of cookies. You are an aeronautics or aerospace engineer and you want to try 3D printing? CAC Wirraway. The second part focuses on complete aircraft, depicting military and commercial single-, twin-, and multi-engine planes. Already have an account? You will be able to create accurate mechanical designs. Formed in , Lockheed Aircraft Corporation was a leading WWII aircraft manufacturer and responsible for the only plane produced throughout the entire war, the P Lightning. Curtiss P-6 Hawk. Aeronautica Lombarda ALP. Wright Flyer Postage Stamp Model. Brewster F2A Buffalo. Skip to the end of the images gallery. Designed as a bomber, it was primarily used in the West, flying daylight missions against Nazi Germany. It first flew in and has been used in many guises, from an airliner to cargo aircraft, and even during the Second World War as a troop transport, cargo carrier, glider tow aircraft or to carry paratroopers. -

44, the Aircraft That Decided World War II

THE FORTY-FOURTH HARMON MEMORIAL LECTURE IN MILITARY HISTORY The Aircraft that Decided World War II: Aeronautical Engineering and Grand Strategy, 1933-1945, The American Dimension John F. Guilmartin, Jr. United States Air Force Academy 2001 The Aircraft that Decided World War II: Aeronautical Engineering and Grand Strategy, 1933-1945, The American Dimension John F. Guilmartin, Jr. The Ohio State University THE HARMON MEMORIAL LECTURES IN MILITARY HISTORY NUMBER FORTY-FOUR United States Air Force Academy Colorado 2001 THE HARMON LECTURES IN MILITARY HISTORY The oldest and most prestigious lecture series at the Air Force Academy, the Harmon Memorial Lectures in Military History originated with Lieutenant General Hubert R. Harmon, the Academy's first superintendent (1954-1956) and a serious student of military history. General Harmon believed that history should play a vital role in the new Air Force Academy curriculum. Meeting with the History Department on one occasion, he described General George S. Patton, Jr.'s visit to the West Point library before departing for the North African campaign. In a flurry of activity Patton and the librarians combed the West Point holdings for historical works that might be useful to him in the coming months. Impressed by Patton's regard for history and personally convinced of history's great value, General Harmon believed that cadets should study the subject during each of their four years at the Academy. General Harmon fell ill with cancer soon after launching the Air Force Academy at Lowry Air Force Base in Denver in 1954. He died in February 1957. He had completed a monumental task over the preceding decade as the chief planner for the new service academy and as its first superintendent. -

IL-2 FB+AEP+PF Aircraft & Cockpit Reference Guide

IL-2 FB+AEP+PF aircraft & cockpit reference guide by neural dream 1 USSR 1.1 Polikarpov I-153 \Tchayka" (Seagull) (`39) The I-153 was a biplane ¯ghter which could also be used for ground attack. Quite slow (366km/h at sea level and 444km/h at 3000m), but able to outturn almost any opponent (12-13.5s turn time at 1000m). The I-153 saw action mainly in the Winter War (1939-40) against the Finns, but was soon withdrawn after the German invasion. Tips: ¦ Consider switching the supercharger to stage 2 over 2000m. Generally avoid high altitudes (>2500m). ¦ Quite surprisingly the I-153 has automatically retractable undercarriage. ¦ Avoid long steep dives; it will start disintegrating before it reaches 600km/h. Armament: M62: upper nose - 2x7.62mm ShKAS (left 700rpg/27sec, right 750rpg/29sec), lower nose - 2x7.62mm ShKAS (left 500rpg/19sec, right 520rpg/19sec). P: nose - 2x20mm ShVAK (left 200rpg/17sec, right 250rpg/21sec). 1. Airspeed indicator 9. Clock 2. Magnetic Compass 10. Cylinder head temperature gauge 3. Tachometer 11. Manifold pressure 4. Altimeter 12. Supercharger lever: rear - stage 1, front - 2 5. Turn and Bank indicator 13. Engine mixture: rear - leaner mixture, 6. Variometer front - richer mixture 7. Engine magnetos position 14. Throttle 8. Oil temperature (upper half), 15. Propeller pitch knob oil pres. (left), fuel pres. (right) 1.2 Polikarpov I-16 \Rata" (`39) Although di±cult to fly and with poor visibility, the I-16 proved a successful ¯ghter which gained the respect of its opponents in Spain in the civil war, in the Far East against the Japanese and during the opening stages of Operation Barbarossa against the Germans.