Hou Nded African Journalists in Exile

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

King and Country: Shakespeare’S Great Cycle of Kings Richard II • Henry IV Part I Henry IV Part II • Henry V Royal Shakespeare Company

2016 BAM Winter/Spring #KingandCountry Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board BAM, the Royal Shakespeare Company, and Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board The Ohio State University present Katy Clark, President Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings Richard II • Henry IV Part I Henry IV Part II • Henry V Royal Shakespeare Company BAM Harvey Theater Mar 24—May 1 Season Sponsor: Directed by Gregory Doran Set design by Stephen Brimson Lewis Global Tour Premier Partner Lighting design by Tim Mitchell Music by Paul Englishby Leadership support for King and Country Sound design by Martin Slavin provided by the Jerome L. Greene Foundation. Movement by Michael Ashcroft Fights by Terry King Major support for Henry V provided by Mark Pigott KBE. Major support provided by Alan Jones & Ashley Garrett; Frederick Iseman; Katheryn C. Patterson & Thomas L. Kempner Jr.; and Jewish Communal Fund. Additional support provided by Mercedes T. Bass; and Robert & Teresa Lindsay. #KingandCountry Royal Shakespeare Company King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings BAM Harvey Theater RICHARD II—Mar 24, Apr 1, 5, 8, 12, 14, 19, 26 & 29 at 7:30pm; Apr 17 at 3pm HENRY IV PART I—Mar 26, Apr 6, 15 & 20 at 7:30pm; Apr 2, 9, 23, 27 & 30 at 2pm HENRY IV PART II—Mar 28, Apr 2, 7, 9, 21, 23, 27 & 30 at 7:30pm; Apr 16 at 2pm HENRY V—Mar 31, Apr 13, 16, 22 & 28 at 7:30pm; Apr 3, 10, 24 & May 1 at 3pm ADDITIONAL CREATIVE TEAM Company Voice -

Medical Management of Biological Casualties Handbook

USAMRIID’s MEDICAL MANAGEMENT OF BIOLOGICAL CASUALTIES HANDBOOK Sixth Edition April 2005 U.S. ARMY MEDICAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE OF INFECTIOUS DISEASES FORT DETRICK FREDERICK, MARYLAND Emergency Response Numbers National Response Center: 1-800-424-8802 or (for chem/bio hazards & terrorist events) 1-202-267-2675 National Domestic Preparedness Office: 1-202-324-9025 (for civilian use) Domestic Preparedness Chem/Bio Helpline: 1-410-436-4484 or (Edgewood Ops Center – for military use) DSN 584-4484 USAMRIID’s Emergency Response Line: 1-888-872-7443 CDC'S Emergency Response Line: 1-770-488-7100 Handbook Download Site An Adobe Acrobat Reader (pdf file) version of this handbook can be downloaded from the internet at the following url: http://www.usamriid.army.mil USAMRIID’s MEDICAL MANAGEMENT OF BIOLOGICAL CASUALTIES HANDBOOK Sixth Edition April 2005 Lead Editor Lt Col Jon B. Woods, MC, USAF Contributing Editors CAPT Robert G. Darling, MC, USN LTC Zygmunt F. Dembek, MS, USAR Lt Col Bridget K. Carr, MSC, USAF COL Ted J. Cieslak, MC, USA LCDR James V. Lawler, MC, USN MAJ Anthony C. Littrell, MC, USA LTC Mark G. Kortepeter, MC, USA LTC Nelson W. Rebert, MS, USA LTC Scott A. Stanek, MC, USA COL James W. Martin, MC, USA Comments and suggestions are appreciated and should be addressed to: Operational Medicine Department Attn: MCMR-UIM-O U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID) Fort Detrick, Maryland 21702-5011 PREFACE TO THE SIXTH EDITION The Medical Management of Biological Casualties Handbook, which has become affectionately known as the "Blue Book," has been enormously successful - far beyond our expectations. -

"How Insults and a Campaign Over

1/30/2018 How insults and a campaign over sanitary towels landed activist in jail | World news | The Guardian How insults and a campaign over sanitary towels landed activist in jail Stella Nyanzi’s attack on her government’s refusal to fund sanitary wear for girls led to a successful crowdfunding campaign, and prison Patience Akumu Sat 22 Apr 2017 19.05 EDT Stella Nyanzi, an academic and formidable campaigner, is languishing in a jail in Kampala for describing her president as “a pair of buttocks”. Uganda’s 72-year-old leader, who came to power more than 30 years ago, has become the subject of ferocious criticism for his government’s treatment of the country’s poor schoolgirls. To Nyanzi, the announcement that her country’s government, under the leadership of President Yoweri Museveni, could not afford to supply sanitary towels to schoolgirls – despite three in every 10 missing school because of menstruation – was more than just another broken campaign promise. It was, to the academic, the epitome of abuse – a symbol of the humiliation that the east African country has endured at the hands of a political monarchy detached from the realities of those it leads. It was also the beginning of an activist journey that would land Nyanzi in a maximum-security prison for insulting the president the west once touted as a poster boy for African democracy. It was first lady Janet Kataaha Museveni – speaking in her position as minister of education – who told parliament in February that there was no money for sanitary towels. Before her husband appointed her to her current post, Janet Museveni was the minister for Karamoja, one of the country’s poorest regions and a hub for illegal gold https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/apr/22/activist-uganda-president-buttocks-jail-stella-nyanzi 1/3 1/30/2018 How insults and a campaign over sanitary towels landed activist in jail | World news | The Guardian mining. -

NEEDLESS DEATHS in the GULF WAR Civilian Casualties During The

NEEDLESS DEATHS IN THE GULF WAR Civilian Casualties During the Air Campaign and Violations of the Laws of War A Middle East Watch Report Human Rights Watch New York $$$ Washington $$$ Los Angeles $$$ London Copyright 8 November 1991 by Human Rights Watch. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Cover design by Patti Lacobee Watch Committee Middle East Watch was established in 1989 to establish and promote observance of internationally recognized human rights in the Middle East. The chair of Middle East Watch is Gary Sick and the vice chairs are Lisa Anderson and Bruce Rabb. Andrew Whitley is the executive director; Eric Goldstein is the research director; Virginia N. Sherry is the associate director; Aziz Abu Hamad is the senior researcher; John V. White is an Orville Schell Fellow; and Christina Derry is the associate. Needless deaths in the Gulf War: civilian casualties during the air campaign and violations of the laws of war. p. cm -- (A Middle East Watch report) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 1-56432-029-4 1. Persian Gulf War, 1991--United States. 2. Persian Gulf War, 1991-- Atrocities. 3. War victims--Iraq. 4. War--Protection of civilians. I. Human Rights Watch (Organization) II. Series. DS79.72.N44 1991 956.704'3--dc20 91-37902 CIP Human Rights Watch Human Rights Watch is composed of Africa Watch, Americas Watch, Asia Watch, Helsinki Watch, Middle East Watch and the Fund for Free Expression. The executive committee comprises Robert L. Bernstein, chair; Adrian DeWind, vice chair; Roland Algrant, Lisa Anderson, Peter Bell, Alice Brown, William Carmichael, Dorothy Cullman, Irene Diamond, Jonathan Fanton, Jack Greenberg, Alice H. -

9/11 Report”), July 2, 2004, Pp

Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page i THE 9/11 COMMISSION REPORT Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page v CONTENTS List of Illustrations and Tables ix Member List xi Staff List xiii–xiv Preface xv 1. “WE HAVE SOME PLANES” 1 1.1 Inside the Four Flights 1 1.2 Improvising a Homeland Defense 14 1.3 National Crisis Management 35 2. THE FOUNDATION OF THE NEW TERRORISM 47 2.1 A Declaration of War 47 2.2 Bin Ladin’s Appeal in the Islamic World 48 2.3 The Rise of Bin Ladin and al Qaeda (1988–1992) 55 2.4 Building an Organization, Declaring War on the United States (1992–1996) 59 2.5 Al Qaeda’s Renewal in Afghanistan (1996–1998) 63 3. COUNTERTERRORISM EVOLVES 71 3.1 From the Old Terrorism to the New: The First World Trade Center Bombing 71 3.2 Adaptation—and Nonadaptation— ...in the Law Enforcement Community 73 3.3 . and in the Federal Aviation Administration 82 3.4 . and in the Intelligence Community 86 v Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page vi 3.5 . and in the State Department and the Defense Department 93 3.6 . and in the White House 98 3.7 . and in the Congress 102 4. RESPONSES TO AL QAEDA’S INITIAL ASSAULTS 108 4.1 Before the Bombings in Kenya and Tanzania 108 4.2 Crisis:August 1998 115 4.3 Diplomacy 121 4.4 Covert Action 126 4.5 Searching for Fresh Options 134 5. -

Becoming a Journalist in Exile

Becoming A Journalist In Exile Author/Editor T. P. Mishra Co-authors R. P. Subba (Bhutan) Subir Bhaumik (India) I. P. Adhikari (Bhutan) C. N. Timsina (Bhutan) Nanda Gautam (Bhutan) Laura Elizabeth Pohl (USA) Deepak Adhikari (Nepal) David Brewer (United Kingdom) Book: Becoming a journalist in exile Publisher: T. P. Mishra for TWMN - Bhutan Chapter Date of publication: March, 2009 Number of copies: 2000 (first edition) Layout: Lenin Banjade, [email protected] ISBN: 978-9937-2-1279-3 Cover design: S.M. Ashraf Abir/www.mcc.com.bd, Bangladesh and Avinash Shrestha, Nepal. Cover: The photo displays the picture of the Chief Editor cum Publisher of The Bhutan Reporter (TBR) monthly, also author of "Becoming a journalist in exile" carrying 1000 issues of TBR (June 2007 edition) from the printing press to his apartment in Kathmandu. Photo: Laura Pohl. Copyright © TWMN – Bhutan Chapter 2009 Finance contributors: Vidhyapati Mishra, I.P. Adhikari, Nanda Gautam, Ganga Neopane Baral, Abi Chandra Chapagai, Harka Bhattarai, Toya Mishra, Parshu Ram Luitel, Durga Giri, Tej Man Rayaka, Rajen Giri, Y. P. Kharel, Bishwa Nath Chhetri, Shanti Ram Poudel, Kazi Gautam and Nandi K. Siwakoti Printed at: Dhaulagiri Offset Press, Kathmandu Price: The price will be sent at your email upon your interest to buy a copy. CONTENTS PART I 1. Basic concepts 1.1 Journalism and news 1.2 Writing for mass media 1.3 Some tips to good journalistic writing 2. Canons of journalism 2.1 The international code of journalist 2.2 Code of ethics 3. Becoming a journalist 4. Media and its role PART II 5. -

Barber Shop Chronicles

Barber Shop Chronicles A Fuel, National Theatre, and West Yorkshire Playhouse co-production WHEN: VENUE: THURSDAY, NOV 8, 7∶30 PM ROBLE STUDIO THEATER FRIDAY, NOV 9, 7∶30 PM SATURDAY, NOV 10, 2∶30 & 7∶30 PM Photo by Dean Chalkley Program Barber Shop Chronicles A Fuel, National Theatre, and West Yorkshire Playhouse co-production Writer Inua Ellams Design Associate Director Bijan Sheibani Catherine Morgan Designer Rae Smith Re-lighter and Production Electrician Lighting Designer Jack Knowles Rachel Bowen Movement Director Aline David Lighting Associate Sound Designer Gareth Fry Laura Howells Music Director Michael Henry Sound Associate Fight Director Kev McCurdy Laura Hammond Associate Director Stella Odunlami Wardrobe Supervisor Associate Director Leian John-Baptiste Louise Marchand-Paris Assistant Choreographer Kwami Odoom Barber Consultant Peter Atakpo Company Voice Work Charmian Hoare Pre-Production Manager Dialect Coach Hazel Holder Richard Eustace Tour Casting Director Lotte Hines Production Manager Sarah Cowan Wallace / Timothy / Mohammed / Tinashe Tuwaine Barrett Company Stage Manager Tanaka / Fifi Mohammed Mansaray Julia Reid Musa / Andile / Mensah Maynard Eziashi Deputy Stage Manager Ethan Alhaji Fofana Fiona Bardsley Samuel Elliot Edusah Assistant Stage Manager Winston / Shoni Solomon Israel Sylvia Darkwa-Ohemeng Tokunbo / Paul / Simphiwe Patrice Naiambana Costume Supervisor Emmanuel Anthony Ofoegbu Lydia Crimp Kwame / Fabrice / Brian Kenneth Omole Costume and Buying Supervisor Olawale / Wole / Kwabena / Simon Ekow Quartey Jessica Dixon Elnathan / Benjamin / Dwain Jo Servi Abram / Ohene / Sizwe David Webber Co-commissioned by Fuel and the National Theatre. Development funded by Arts Council England with the support of Fuel, National Theatre, West Yorkshire Playhouse, The Binks Trust, British Council ZA, Òran Mór and A Play, a Pie and a Pint. -

First Lady Hosts Her Ethiopian Counterpart

4 NEW VISION, Wednesday March 8, 2017 NATIONAL NEWS HIV/AIDS Prevention Pregnancies Nutrition By Vision Reporter The two ladies The First Lady and Minister of Education and Sports, Janet Museveni, First Lady hosts her shared experiences has hosted her counterpart Roman Tesfaye Abneh, wife of the Ethiopian prime minister who was in Uganda on the work they accompanying her husband on a three-day state visit last week. do under the The two First Ladies held a meeting Ethiopian counterpart at State House Entebbe on Thursday, during which they shared experiences Organisation of on the work they both do, among this the activities under the Organisation of African First Ladies Against HIV/ African First Ladies AIDS (OAFLA) in their respective countries. Against HIV/AIDS The meeting was also attended by the Minister of Gender Labour and Social Development, Hajat Janat in their respective Mukwaya; the UNAIDS Resident Representative, Sande Amakobe; countries UNICEF Representative Aida Girma, UNFPA Representative Miranda Tadifor, executive director for Uganda mother-to-child transmission of AIDS Commission Dr Christine HIVAIDS in Uganda and saluted Ondoa, the executive director OAFLA Uganda for reaching that level. Uganda, Beatilda Bisangwa and MPs She said in their country, they who are champions against HIV/AIDS use the door–to-door approach to among children and adolescents. sensitise the people on the prevention Janet Museveni, who is the founder and treatment of HIV/AIDS. and patron of the Organisation of African First Ladies Against HIV/ Resisting modern practices AIDS — Uganda Chapter (OAFLA-U, Tesfaye, however, noted that they observed that for Uganda to attain a still face a big challenge of some HIV/AIDS-free generation, there is communities who are not easy to need to ensure that all children born mobilise because they largely follow are without infection and that all the traditional beliefs and have not yet infected adults are put on treatment fully embraced the modern approach and encouraged not to spread the of preventing HIV/AIDS. -

Music in Irish Emigration Literature

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2017 Singing exile: Music in Irish emigration literature Christopher McCann The University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details McCann, C. (2017). Singing exile: Music in Irish emigration literature (Master of Arts (Thesis)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/166 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Singing Exile: Music in Irish Emigration Literature by Christopher McCann A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts (Research) at the University of Notre Dame Australia (Fremantle) June 2017 Contents Abstract iii Acknowledgements v Introduction 1 Chapter One: The Revival Cultural Field and Exile: George Moore and James Joyce 13 Chapter Two: Traditional Music and the Post-Independence Exodus to Britain 43 Chapter Three: Between Two Worlds: Music at the American wake 66 Chapter Four: “Os comhair lán an tí”: Sean-nós as a site of memory in Brooklyn 93 Chapter Five: Imagined Geography and Communal Memory in Come Back to Erin 120 Conclusion 144 Appendix: Annotated Discography 150 Bibliography 158 ii Abstract Ireland possesses a cultural heritage that is particularly literary and musical. -

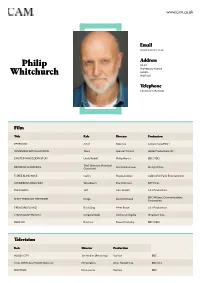

Philip Whitchurch

www.cam.co.uk Email [email protected] Address Philip 55-59 Shaftesbury Avenue London Whitchurch W1D 6LD Telephone +44 (0) 20 7292 0600 Film Title Role Director Production PETERLOO Actor Mike Lee Cornerstone/Film4 INTERVIEW WITH A HITMAN Tosca Spencer Pollard IWAH Productions Ltd EINSTEIN AND EDDINGTON Uncle Rudolf Philip Martin BBC/HBO The Fisherman (Principal BEOWULF & GRENDEL Sturla Gunnerson Arclight Films Character) THREE BLIND MICE Carlin Matias Ledoux Caldera/De Fanti Entertainment WONDROUS OBLIVION Woodberry Paul Morrison APT Films PUNCHBAG Jeff John Shaikh J & J Productions BBC/Alliance Communications SHOT THROUGH THE HEART Drago David Attwood Corporation TREASURE ISLAND Black Dog Peter Rowe J & J Productions THE ENGLISH PATIENT Corporal Dade Anthony Mingella Miramax Films BLUE ICE Blackner Russell Mulcahy BBC/HBO Television Role Director Production HOLBY CITY Jim Mullins (Recurring) Various BBC STILL OPEN ALL HOURS (Series 5) Mr Venables Dewi Humphreys BBC One DOCTORS Eric Leverty Various BBC HOLBY CITY Kenny Devereaux Alan Wareing BBC DOORS OPEN The Geordie Marc Evans Doors Closed Ltd. STARLINGS Morris Charon Matt Lipsey & Tony Dow Sky 1 SILENT WITNESS Graham Ferris Keith Boak BBC TAGGART Alamo Higgins Douglas Mackinnon ITV CASUALTY Millard Declan O'Dwyer BBC PLACE OF EXECUTION DCI Culver Daniel Percival ITV WAKING THE DEAD Jim Brown Ed Bennett BBC BLUE MURDER Roy Gant Graham Theakston ITV DOCTORS Jake Myers Terry Ireland ITV HOLBY CITY Thomas Brandon Various Directors BBC MACBETH Harry Dibby Mark Brazel BBC MY HERO Tyler -

"Magic City" Class, Community, and Reform in Roanoke, Virginia, 1882-1912 Paul R

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 "Magic City" class, community, and reform in Roanoke, Virginia, 1882-1912 Paul R. Dotson, Jr. Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Dotson, Jr., Paul R., ""Magic City" class, community, and reform in Roanoke, Virginia, 1882-1912" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 68. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/68 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. “MAGIC CITY” CLASS, COMMUNITY, AND REFORM IN ROANOKE, VIRGINIA, 1882-1912 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Paul R. Dotson, Jr. B. A. Roanoke College, 1990 M. A. Virginia Tech, 1997 December 2003 For Herman, Kathleen, Jack, and Florence ii Between the idea And the reality Between the motion And the act Falls the Shadow T. S. Eliot, “The Hollow Men” (1925) iii Acknowledgements Gaines Foster shepherded this dissertation from the idea to the reality with the sort of patience, encouragement, and guidance that every graduate student should be so lucky to receive. A thanks here cannot do justice to his efforts, but I offer it anyway with the hope that one day I will find a better method of acknowledging my appreciation. -

Hou Nded African Journalists in Exile

Hou nded African Journalists in Exile Edited by Joseph Odindo www.kas.de Hounded: African Journalists in Exile Hounded: African Journalists in Exile Edited by Joseph Odindo Published by Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung Regional Media Programme Sub-Sahara Africa 60 Hume Road PO Box 55012 Dunkeld 2196 Northlands Johannesburg 2116 Republic of South Africa Telephone: + 27 (0)11 214-2900 Telefax: +27 (0)11 214-2913/4 www.kas.de/mediaafrica Twitter: @KASMedia Facebook: @KASMediaAfrica ISBN: 978-0-620-89940-6 (print) 978-0-620-89941-3 (e-book) © Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, 2021 This publication is an open source publication. Parts thereof may be reproduced or quoted provided the publication is fully acknowledged as the source thereof. Download an electronic copy of Hounded: African Journalists in Exile from www.kas.de/hounded-african-journalists-in-exile Cover photograph: Gallo Images / Getty Images Proofreader: Bruce Conradie Translator: Jean-Luc Mootoosamy (Chapters 4, 9 and 10 were translated from French) Layout and Heath White, ihwhiteDesign production: [email protected] Printing: Typo Printing Investments, Johannesburg, South Africa Table of contents Foreword ix Christoph Plate, KAS Media Africa Right to publish must be grabbed 1 Joseph Odindo, Editor 1. Guerrillas in the newsroom 5 Dapo Olorunyomi, Nigeria 2. Nightmare of news, guns and dollars 15 Kiwanuka Lawrence Nsereko, Uganda 3. A scoop and the general’s revenge 23 Keiso Mohloboli, Lesotho 4. Haunted by a political blog 31 Makaila N’Guebla, Chad 5. Nine Zones and a passion for justice 41 Soleyana Shimeles Gebremichael, Ethiopia v Hounded: African Journalists in Exile 6. Through Gambia’s halls of injustice 51 Sainey MK Marenah, The Gambia 7.