Music Samizdat As Zines? the Case of Ot Vinta from Soviet Latvia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Day Holding Hands Changed History Occupation and Annexation of the Baltic States Was Illegal, and Against the Wish of the Respective Nations

The day holding hands changed history occupation and annexation of the Baltic states was illegal, and against the wish of the respective nations. So at 19:00 on 23 August 1989, 50 years after the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact was signed, church bells sounded in the Bal- tic states. Mourning ribbons decorated the national flags that had been banned a year before. The participants of the Bal- tic Way were addressed by the leaders of the respective national independence movements: the Estonian Rahvarinne, the Lithuanian Sajūdis, and the Popular Front of Latvia. The following words were chanted – ‘laisvė’, ‘svabadus, ‘brīvība’ (freedom). The symbols of Nazi Germany and the Communist regime of the USSR were burnt on large bonfires. The Baltic states demanded the cessation of the half-century long Soviet occupation, col- onisation, russification and communist genocide. The Baltic Way was a significant step to- wards regaining the national independ- ence of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia, and a source of inspiration for other region- al independence movements. The live chain was also realised in Kishinev by Ro- manians of the Soviet-occupied Bessara- bia or Moldova, while in January 1990, Ukrainians joined hands on the road from Lviv to Kyiv. Just after the Baltic Way campaign, the Berlin Wall fell, the Velvet Revolution in Czechoslovakia began, and the Ceausescu regime in Romania was overthrown. On 23 August 1989, approximately two doomed to be forcedly incorporated into million people stood hand in hand be- the Soviet Union until 1991. The Soviet Un- Recognising the documents of the Baltic tween Tallinn (Estonia), Rīga (Latvia) ion claimed that the Baltic states joined Way as items of documentary heritage of and Vilnius (Lithuania) in one of the voluntarily. -

An Investigation Into the Effects of Cultural Policies on National Identity

Cultural Policy in Lithuania since the 1980s: An Investigation into the Effects of Cultural Policies on National Identity MA Thesis in European Studies Graduate School for Humanities Universiteit van Amsterdam Author Laisvė Linkutė Student number 10394192 Main Supervisor Dhr. Dr. G.J.A. Snel Second Supervisor Dhr. Dr. M.E. Spiering August, 2013 1 Laisve Linkute 10394192 In memory of my father Algirdas 2 Laisve Linkute 10394192 Contents: Abstract: ............................................................................................................................................................ 4 Introduction: ...................................................................................................................................................... 5 First chapter: Lithuania in the Soviet Union ...................................................................................................... 9 Second Chapter: Transition to democracy ...................................................................................................... 22 Third Chapter: Lithuania in the EU .................................................................................................................. 33 Conclusions: ..................................................................................................................................................... 47 Bibliography: .................................................................................................................................................... 49 3 -

1: Introduction

Working Papers WP 2013-02 Centre for German and European Studies (CGES) Ksenia Maksimovtsova Contemporary Debates over Language Policy regarding Ethnic Minorities in Latvia and Ukraine: The Discourse of Russian-Language Press. WP 2013-02 2013 № 2 Bielefeld / St. Petersburg Working Papers WP 2013-02 Centre for German and European Studies Bielefeld University St. Petersburg State University Centre for German and European Studies (CGES) CGES Working Papers series includes publication of materials prepared within different activities of the Center for German and European Studies both in St. Petersburg and in Germany: The CGES supports educational programmes, research and scientific dialogues. In accordance with the CGES mission, the Working Papers are dedicated to the interdisciplinary studies of different aspects of German and European societies. The paper is written on the basis of the MA Thesis defended in the MA SES in June 2013 supervised by Dr. Anisya Khokhlova. The author’s internship at the European Centre for Minority Issues in Flensburg, Germany and autumn exchange semester at the University of Bielefeld made an invaluable contribution to the following research project. The publication of the MA thesis in the CGES Working Paper series was recommended by the Examination Committee as one of the best papers out of five MA theses defended by the students of the MA Programme ‘’Studies in European Societies’’ at St. Petersburg State University in June 2013. Ksenia Maksimovtsova graduated from the Faculty of Liberal Arts and Sciences of St. Petersburg State University in 2011 (Major in International Relations, Political Science and Human Rights). Her academic interests include theories of nationalism, language policy, ethnic identity, bilingualism and post-Soviet transformations. -

Travel Guide

TRAVEL GUIDE Traces of the COLD WAR PERIOD The Countries around THE BALTIC SEA Johannes Bach Rasmussen 1 Traces of the Cold War Period: Military Installations and Towns, Prisons, Partisan Bunkers Travel Guide. Traces of the Cold War Period The Countries around the Baltic Sea TemaNord 2010:574 © Nordic Council of Ministers, Copenhagen 2010 ISBN 978-92-893-2121-1 Print: Arco Grafisk A/S, Skive Layout: Eva Ahnoff, Morten Kjærgaard Maps and drawings: Arne Erik Larsen Copies: 1500 Printed on environmentally friendly paper. This publication can be ordered on www.norden.org/order. Other Nordic publications are available at www.norden.org/ publications Printed in Denmark T R 8 Y 1 K 6 S 1- AG NR. 54 The book is produced in cooperation between Øhavsmuseet and The Baltic Initiative and Network. Øhavsmuseet (The Archipelago Museum) Department Langelands Museum Jens Winthers Vej 12, 5900 Rudkøbing, Denmark. Phone: +45 63 51 63 00 E-mail: [email protected] The Baltic Initiative and Network Att. Johannes Bach Rasmussen Møllegade 20, 2200 Copenhagen N, Denmark. Phone: +45 35 36 05 59. Mobile: +45 30 25 05 59 E-mail: [email protected] Top: The Museum of the Barricades of 1991, Riga, Latvia. From the Days of the Barricades in 1991 when people in the newly independent country tried to defend key institutions from attack from Soviet military and security forces. Middle: The Anna Akhmatova Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia. Handwritten bark book with Akhmatova’s lyrics. Made by a GULAG prisoner, wife of an executed “enemy of the people”. Bottom: The Museum of Genocide Victims, Vilnius, Lithuania. -

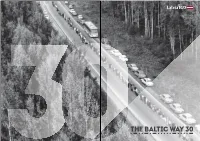

The Baltic Way Towards Freedom

THE BALTIC The Baltic Way WAY 30 Towards Freedom At 19:00 on 23 August 1989 approximately two million people of the Baltic states joined hands forming a live, continuous chain on the road Tallinn-Rīga-Vilnius (660-670 km). Church bells sounded in the Baltic states. Mourning ribbons decorated the national flags that were banned a year ago. The participants of the Baltic Way were addressed by the leaders of Rahvarinne - the Estonian Popular Front, the Lithuanian movement Sajūdis and the Popular Front of Latvia. The following words were heard – ‘laisvė’, ‘svabadus, ‘brīvība’ (freedom). The symbols of Nazi Germany and the Communist regime of the USSR were burned in large bonfires. Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania engaged in collective action against the non-assault agreement between Hitler and Stalin of 23 August 1939 and its secret protocols or the “devil pact”. The Baltic states demanded the cessation of half-century long Soviet occupation, colonisation, russification and Photo 1 (cover photo) communist genocide. The Baltic Way became the The Baltic Way on Pleskava highway. crucial application by the Baltic states’ civil society The photo was taken from the helicopter for independence and return to Europe. It was the on 23 August 1989. first dice in the domino effect that disrupted the Photographer Aivars Liepiņš. Archive of the Latvian Institute. totalitarian regime in Eastern Europe - the first step towards regaining national independence of Latvia. © State Chancellery of Latvia, 2019 THE BALTIC WAY 30 1 2 THE BALTIC WAY 30 Photo 2 Causes and Participants of the Baltic Way on the Stone Bridge (at that time the October Bridge). -

Latvia 1988-2015: a Triumph of the Radical Nationalists

The Baltic Centre of Historical and Socially Political Studies Victor Gushchin Latvia 1988-2015: a triumph of the radical nationalists Political support of the West for Latvian radical nationalism and neo-Nazismand the import of this ideology into Latvia after the West’s victory in the Cold War. Formation of a unipolar world led by the USA, revision of the 1945 Yalta and Potsdam treaties and the 1975 Helsinki Final Act of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe as main reasons for the evolution of the Republic of Latvia of May 4th, 1990,from elimination of universal suffrage to relapse of totalitarianism: establishment of the so-called «Latvian Latvia», Russophobia, suppression of ethnic minority rights, restriction of freedom of speech and assembly, revision of the outcome of World War Two and propaganda of neo-Nazism. Riga 2017 UDK 94(474.3) “19/20” Gu 885 The book Latvia 1988-2015: a triumph of the radical nationalists» is dedicated to Latvia’s most recent history. On May 4, 1990, the Supreme Soviet (Supreme Council) of the Latvian SSR adopted the Declaration on the Restoration of Independence of the Latvian Republic without holding a national referendum, thus violating the acting Constitution. Following this up on October 15, 1991, the Supreme Soviet deprived more than a third of its own electorate Latvia 1988 - 2015: of the right to automatic citizenship. As a result, one of the most fundamental principles of a triumph of the radical nationalists democracy, universal suffrage, was eliminated. Thereafter, the Latvian parliament, periodically re-elected in conditions where a signif- icant part of country’s inhabitants lack the right to participate in elections, has been adopting Book 1. -

Memory of the World Register

MEMORY OF THE WORLD REGISTER The Baltic Way Human Chain Linking Three States in Their Drive for Freedom (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania) Ref N° 2008-05 PART A – ESSENTIAL INFORMATION 1 SUMMARY The documentary heritage proposed for inscription in the Memory of the World Register by Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania includes significant and carefully selected documents reflecting the history of the 600 km long human chain - a unique and peaceful demonstration that united the three countries in their drive for freedom on 23 August 1989, the 50th anniversary of the German-Soviet non-aggression pact of 1939 and its secret protocol. On 23 August 1939 foreign ministers of the USSR and Germany - Vyacheslav Molotov and Joachim von Ribbentrop- as ordered by their superiors Stalin and Hitler, signed a treaty which affected the fate of Europe and the entire world. This pact, and the secret clauses it contained, divided the spheres of influence of the USSR and Germany and led to World War II, and to the occupation of the three Baltic States - Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. 50 years later, on 23 August 1989, the three nations living by the Baltic Sea surprised the world by taking hold of each other’s hands and jointly demanding recognition of the secret clauses in the Molotov- Ribbentrop pact and the re-establishment of the independence of the Baltic States. More than a million people joined hands to create a 600 km long human chain from the foot of Toompea in Tallinn to the foot of the Gediminas Tower in Vilnius, crossing Riga and the River Daugava on its way, creating a synergy in the drive for freedom that united the three countries. -

The Ethnopolitical Movement As a Vehicle for Nationalism Institutionalisation in Modern Latvia

SOCIAL DYNAMICS THE ETHNOPOLITICAL MOVEMENT AS A VEHICLE FOR NATIONALISM INSTITUTIONALISATION IN MODERN LATVIA E. Е. Urazbaev a E. N. Yamalova b a Immanuel Kant Baltic Federal University Received 21 October 2019 14A Nevskogo St., Kaliningrad, 236016, Russia doi: 10.5922/2079-8555-2020-2-4 b Bashkir State University © Urazbaev E. Е., Yamalova E. N., 2020 32 Zaki Validi St., Republic of Bashkortostan, Ufa, 450076, Russia This article investigates the Popular Front of Latvia, a public ethnopolitical movement that substantially contributed to the independence of the modern Republic of Latvia. The study aims to identify how much the movement influenced the development of ethnic na- tionalism, which has become essential to statehood and the identification of politics. It continues to reinforce group inequality in this multiethnic country. The article describes the background and main landmarks of the movement. Content analysis of manifestos has been carried out to trace changes in the Popular Front’s ideological vision. It is shown that the shift in priorities that took place during the 1988—1991 struggle for Latvia’s po- litical and economic independence led to a non-democratic political regime. Particular attention is paid to the movement’s proposals concerning the principles of statehood res- toration and citizenship acquisition as well as to approaches to solving ethnic problems. The focus is on why and under what circumstances the Popular Front dissolved itself and the supra-ethnic opposition, its main rivals, left the political scene. It is argued that the Popular Front of Latvia created conditions both for the titular nation taking precedence over other ethnic groups and for the exclusion of one-third of the country’s resident popu- lation from political life. -

Recruitment and Careers of Legislators in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, 1990-2012

Transformation of Parliamentary Elites: Recruitment and Careers of Legislators in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, 1990-2012 Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades doctor philosophiae (Dr. phil.) vorgelegt dem Rat der Fakultät für Sozial- und Verhaltenswissenschaften der Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena von M.Phil. Mindaugas Kuklys geboren am 12. Januar 1974 in Kretinga TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 4 1. Parliamentary recruitment and theory of elites 7 1.1. The recruitment process 7 1.2. Elite circulation as a link between parliamentary recruitment and democratic elitism 11 1.2.1. Heritage of modern Machiavellians 11 1.2.2. Democratic elitism since Max Weber and Joseph Schumpeter 15 1.3. Changes in social and political background of legislators as an indicator of parliamentary elite transformation 18 2. Elite transformation in Eastern Europe after 1989: A literature review 22 2.1. Linking the type of elite, regime and circulation 23 2.2. Professionalisation of parliamentary elites 25 2.3. Different elites for each phase of social and political change 26 2.4. Theory of elite control and the elite network state 27 2.5. Political capitalism, conversion of power and the “grand coalition” 28 2.6. Post-Communist managerialism and the dominance of cultural capital 29 2.7. Other studies 30 2.8. Summary: Issues of elite/class and circulation/reproduction 32 2.9. Literature on the recruitment and transformation of elites in the Baltics 34 3. Comparative method and the longitudinal data on the Baltic parliamentary elites 38 3.1. Data set on the Baltic parliamentary elites and challenges of classification 43 3.2. -

Official Islam in Russia: an Analysis of Past and Present

OFFICIAL ISLAM IN RUSSIA: AN ANALYSIS OF PAST AND PRESENT A Master’s Thesis by MUHAMMET KOÇAK Department of International Relations İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University Ankara September 2015 OFFICIAL ISLAM IN RUSSIA: AN ANALYSIS OF PAST AND PRESENT Graduate School of Economics and Social Sciences of İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University by MUHAMMET KOÇAK In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in THE DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS İHSAN DOĞRAMACI BİLKENT UNİVERSİTY ANKARA September 2015 I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in International Relations. --------------------------- Associate Prof. Hakan Kırımlı Supervisor I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in International Relations. --------------------------- Prof. Dr. İbrahim Maraş Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in International Relations. --------------------------- Assistant Prof. Onur İşçi Examining Committee Member Approval of the Graduate School of Economics and Social Sciences --------------------------- Prof. Dr. Erdal Erel Director ABSTRACT OFFICIAL ISLAM IN RUSSIA: AN ANALYSIS OF PAST AND PRESENT Koçak, Muhammet M.A., The Department of International Relations Supervisor: Associate Prof. Hakan Kırımlı September 2015 In this thesis, the properties of the official Islamic institutions in Russia are analyzed. Starting from Catherine II, Russia developed a religious-centered approach towards its Muslim subjects. -

January 1991

January 2021 Länderbüro, Lettland Photo: Witold Hussakowski. Collection of the Latvian National Museum. January 1991 Barricades in Latvia Dainis Īvāns On 18 November 1918, the People’s Council of Latvia, founded by Latvian political parties, declared the Republic of Latvia de jure. However, actual independence had to be fought for with weapons and there were casualties. The Latvian War of Independence lasted two long years. On 4 May 1990, the Supreme Council of Latvia, elected in the first free elections of the Latvian SSR, declared restoration of the independence of the Republic of Latvia de jure. What followed this time, was nonviolent resistance under the auspices of the newly elected parliament, so as to regain independence de facto. We used no weapons, just our bare hands and the power of the nation’s spirit. There were casualties. The decisive battle came in January 1991. The impulse for these events can be traced back, if not to 23 August 1939 when the Hitler-Stalin Pact was signed in Moscow, then definitely to 23 August 1989. On the 50th anniversary of this pact 2 million Latvians, Lithuanians and Estonians joined their hands to form a human chain for 640 km - the Baltic Way. Despite Moscow’s denial of the existence of a secret deal between Hitler and Stalin, defining the spheres of influence and claiming that the Baltic states had acceded to the Soviet Union voluntarily, the truth was not to be hidden any longer. Upon request by members of the Estonian Popular Front, the Lithuanian Sajudis and the Latvian Popular Front, a parliamentary enquiry commission Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e. -

The Ethnopolitical Movement As a Vehicle For

www.ssoar.info The ethnopolitical movement as a vehicle for nationalism institutionalisation in modern Latvia Urazbaev, E.; Yamalova, E. N. Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Urazbaev, E., & Yamalova, E. (2020). The ethnopolitical movement as a vehicle for nationalism institutionalisation in modern Latvia. Baltic Region, 12(3), 54-69. https://doi.org/10.5922/2079-8555-2020-2-4 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC Lizenz (Namensnennung- This document is made available under a CC BY-NC Licence Nicht-kommerziell) zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu (Attribution-NonCommercial). For more Information see: den CC-Lizenzen finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/deed.de Diese Version ist zitierbar unter / This version is citable under: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-70222-9 SOCIAL DYNAMICS THE ETHNOPOLITICAL MOVEMENT AS A VEHICLE FOR NATIONALISM INSTITUTIONALISATION IN MODERN LATVIA E. Е. Urazbaev a E. N. Yamalova b a Immanuel Kant Baltic Federal University Received 21 October 2019 14A Nevskogo St., Kaliningrad, 236016, Russia doi: 10.5922/2079-8555-2020-2-4 b Bashkir State University © Urazbaev E. Е., Yamalova E. N., 2020 32 Zaki Validi St., Republic of Bashkortostan, Ufa, 450076, Russia This article investigates the Popular Front of Latvia, a public ethnopolitical movement that substantially contributed to the independence of the modern Republic of Latvia. The study aims to identify how much the movement influenced the development of ethnic na- tionalism, which has become essential to statehood and the identification of politics.