The Baltic States

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Download

Ajalooline Ajakiri, 2016, 3/4 (157/158), 477–511 Historical consciousness, personal life experiences and the orientation of Estonian foreign policy toward the West, 1988–1991 Kaarel Piirimäe and Pertti Grönholm ABSTRACT The years 1988 to 1991 were a critical juncture in the history of Estonia. Crucial steps were taken during this time to assure that Estonian foreign policy would not be directed toward the East but primarily toward the integration with the West. In times of uncertainty and institutional flux, strong individuals with ideational power matter the most. This article examines the influence of For- eign Minister Lennart Meri’s and Prime Minister Edgar Savisaar’s experienc- es and historical consciousness on their visions of Estonia’s future position in international affairs. Life stories help understand differences in their horizons of expectation, and their choices in conducting Estonian diplomacy. Keywords: historical imagination, critical junctures, foreign policy analysis, So- viet Union, Baltic states, Lennart Meri Much has been written about the Baltic states’ success in breaking away from Eastern Europe after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, and their decisive “return to the West”1 via radical economic, social and politi- Research for this article was supported by the “Reimagining Futures in the European North at the End of the Cold War” project which was financed by the Academy of Finland. Funding was also obtained from the “Estonia, the Baltic states and the Collapse of the Soviet Union: New Perspectives on the End of the Cold War” project, financed by the Estonian Research Council, and the “Myths, Cultural Tools and Functions – Historical Narratives in Constructing and Consolidating National Identity in 20th and 21st Century Estonia” project, which was financed by the Turku Institute for Advanced Studies (TIAS, University of Turku). -

The Day Holding Hands Changed History Occupation and Annexation of the Baltic States Was Illegal, and Against the Wish of the Respective Nations

The day holding hands changed history occupation and annexation of the Baltic states was illegal, and against the wish of the respective nations. So at 19:00 on 23 August 1989, 50 years after the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact was signed, church bells sounded in the Bal- tic states. Mourning ribbons decorated the national flags that had been banned a year before. The participants of the Bal- tic Way were addressed by the leaders of the respective national independence movements: the Estonian Rahvarinne, the Lithuanian Sajūdis, and the Popular Front of Latvia. The following words were chanted – ‘laisvė’, ‘svabadus, ‘brīvība’ (freedom). The symbols of Nazi Germany and the Communist regime of the USSR were burnt on large bonfires. The Baltic states demanded the cessation of the half-century long Soviet occupation, col- onisation, russification and communist genocide. The Baltic Way was a significant step to- wards regaining the national independ- ence of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia, and a source of inspiration for other region- al independence movements. The live chain was also realised in Kishinev by Ro- manians of the Soviet-occupied Bessara- bia or Moldova, while in January 1990, Ukrainians joined hands on the road from Lviv to Kyiv. Just after the Baltic Way campaign, the Berlin Wall fell, the Velvet Revolution in Czechoslovakia began, and the Ceausescu regime in Romania was overthrown. On 23 August 1989, approximately two doomed to be forcedly incorporated into million people stood hand in hand be- the Soviet Union until 1991. The Soviet Un- Recognising the documents of the Baltic tween Tallinn (Estonia), Rīga (Latvia) ion claimed that the Baltic states joined Way as items of documentary heritage of and Vilnius (Lithuania) in one of the voluntarily. -

London School of Economics and Political Science Department of Government

London School of Economics and Political Science Department of Government Historical Culture, Conflicting Memories and Identities in post-Soviet Estonia Meike Wulf Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD at the University of London London 2005 UMI Number: U213073 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U213073 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Ih c s e s . r. 3 5 o ^ . Library British Library of Political and Economic Science Abstract This study investigates the interplay of collective memories and national identity in Estonia, and uses life story interviews with members of the intellectual elite as the primary source. I view collective memory not as a monolithic homogenous unit, but as subdivided into various group memories that can be conflicting. The conflict line between ‘Estonian victims’ and ‘Russian perpetrators* figures prominently in the historical culture of post-Soviet Estonia. However, by setting an ethnic Estonian memory against a ‘Soviet Russian’ memory, the official historical narrative fails to account for the complexity of the various counter-histories and newly emerging identities activated in times of socio-political ‘transition’. -

Separatist Versus Centrist Forces in the Ussr, 1988-1991: Explaining the Collapse of the Soviet Internal Empire by a Strategic Alliance Approach

********************************************************* SEPARATIST VERSUS CENTRIST FORCES IN THE USSR, 1988-1991: EXPLAINING THE COLLAPSE OF THE SOVIET INTERNAL EMPIRE BY A STRATEGIC ALLIANCE APPROACH COMPARING THE BALTIC AND THE TRANSCAUCASIAN CASES: A PROGRESS REPORT By Caspar ten Dam ********************************************************* Seminar “Soviet Internal Empire: Establishment, Daily Working and Dissolution”, by Prof. Mette Skak ERASMUS, st.nr.923488 September 1993 Reproduced & proofread for publication: March 2015 CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION: Determinism within Sovietology and Why a Strategic Alliance Approach is Chosen 4 CHAPTER 1: Aspects of Strategic Alliance 8 1.1. Alignments and Realignments among Centrist and Separatist Forces, and Types of Organization 8 1.2. Typologies of Political Groups, based on the Centrist-Separatist Divide 9 CHAPTER 2. The Baltics: Successful Separatism by Moderate Senior-Junior Partnership Alliances between the Popular Fronts and the Republican Communist Parties 14 2.1. 1988: the establishments of the Popular Fronts - and Different Degrees of Cooperation with the Communist Parties 14 2.2. 1989: the Establishments of Moderate Alliances between the Popular Fronts and the Communist Parties, and the Rising Challenges of the Radical Congress Movements 17 2.3. 1990: the Moderate/Radical CP-PF Alliances fared Differently in each Republic, and the Radical Congress Alliances had Different Rates of Success 21 2.4. 1991: the Year of Allying Dangerously 25 2.5. Conclusion 30 CHAPTER 3. The Transcaucasus: Successful Ethnonationalism and Weak Separatism by Extremist Antagonistic Blocs 32 3.1. 1988: the Establishment of Nationalist Movements against the Wishes of Conservative-Reactionary Elites 32 3.2. 1989: the Rise of Extremist Nationalism, Superseding Statist Separatism, and the Failure to Establish Strategic Alliances among the Communist Parties and Opposition Movements 36 3.3. -

Politics, Migration and Minorities in Independent and Soviet Estonia, 1918-1998

Universität Osnabrück Fachbereich Kultur- und Geowissenschaften Fach Geschichte Politics, Migration and Minorities in Independent and Soviet Estonia, 1918-1998 Dissertation im Fach Geschichte zur Erlangung des Grades Dr. phil. vorgelegt von Andreas Demuth Graduiertenkolleg Migration im modernen Europa Institut für Migrationsforschung und Interkulturelle Studien (IMIS) Neuer Graben 19-21 49069 Osnabrück Betreuer: Prof. Dr. Klaus J. Bade, Osnabrück Prof. Dr. Gerhard Simon, Köln Juli 2000 ANDREAS DEMUTH ii POLITICS, MIGRATION AND MINORITIES IN ESTONIA, 1918-1998 iii Table of Contents Preface...............................................................................................................................................................vi Abbreviations...................................................................................................................................................vii ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................ VII 1 INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................3 1.1 CONCEPTUAL AND METHODOLOGICAL ISSUES ...............................................4 1.1.1 Conceptualising Migration ..................................................................5 1.1.1.1 Socio-Historical Migration Research....................................................................................5 1.1.1.2 A Model of Migration..........................................................................................................6 -

An Investigation Into the Effects of Cultural Policies on National Identity

Cultural Policy in Lithuania since the 1980s: An Investigation into the Effects of Cultural Policies on National Identity MA Thesis in European Studies Graduate School for Humanities Universiteit van Amsterdam Author Laisvė Linkutė Student number 10394192 Main Supervisor Dhr. Dr. G.J.A. Snel Second Supervisor Dhr. Dr. M.E. Spiering August, 2013 1 Laisve Linkute 10394192 In memory of my father Algirdas 2 Laisve Linkute 10394192 Contents: Abstract: ............................................................................................................................................................ 4 Introduction: ...................................................................................................................................................... 5 First chapter: Lithuania in the Soviet Union ...................................................................................................... 9 Second Chapter: Transition to democracy ...................................................................................................... 22 Third Chapter: Lithuania in the EU .................................................................................................................. 33 Conclusions: ..................................................................................................................................................... 47 Bibliography: .................................................................................................................................................... 49 3 -

1: Introduction

Working Papers WP 2013-02 Centre for German and European Studies (CGES) Ksenia Maksimovtsova Contemporary Debates over Language Policy regarding Ethnic Minorities in Latvia and Ukraine: The Discourse of Russian-Language Press. WP 2013-02 2013 № 2 Bielefeld / St. Petersburg Working Papers WP 2013-02 Centre for German and European Studies Bielefeld University St. Petersburg State University Centre for German and European Studies (CGES) CGES Working Papers series includes publication of materials prepared within different activities of the Center for German and European Studies both in St. Petersburg and in Germany: The CGES supports educational programmes, research and scientific dialogues. In accordance with the CGES mission, the Working Papers are dedicated to the interdisciplinary studies of different aspects of German and European societies. The paper is written on the basis of the MA Thesis defended in the MA SES in June 2013 supervised by Dr. Anisya Khokhlova. The author’s internship at the European Centre for Minority Issues in Flensburg, Germany and autumn exchange semester at the University of Bielefeld made an invaluable contribution to the following research project. The publication of the MA thesis in the CGES Working Paper series was recommended by the Examination Committee as one of the best papers out of five MA theses defended by the students of the MA Programme ‘’Studies in European Societies’’ at St. Petersburg State University in June 2013. Ksenia Maksimovtsova graduated from the Faculty of Liberal Arts and Sciences of St. Petersburg State University in 2011 (Major in International Relations, Political Science and Human Rights). Her academic interests include theories of nationalism, language policy, ethnic identity, bilingualism and post-Soviet transformations. -

Music Samizdat As Zines? the Case of Ot Vinta from Soviet Latvia

Music Samizdat as Zines? The Case of “Ot Vinta” from Soviet Latvia Jānis Daugavietis Abstract DAUGAVIETIS, Jānis: Music Samizdat as Zines? The Case of “Ot Vinta” from Soviet Latvia. The conceptual problem this article aims to research is how zines (of the Western or “the first world”) and music samizdat (of socialist countries or “the second world”) should be analysed. Thus far, they have been regarded as separate phenomena; however, do these two forms of underground literature differ so greatly that they should be analysed using different theoretical approaches? The subject of the paper, От Винта (Ot Vinta), is a Russian-language music samizdat from the Latvian Soviet Socialist Republic which was published in the late Soviet period. It came out in Riga between 1987 and 1991 and was closely connected to the local underground and semi-official rock scene. As Soviet music samizdat is an under-researched topic, and the Latvian one is practically unexplored, an important part of the pa- per is devoted to a description of this field and the context in which it appeared. The paper also explores the history of Ot Vinta, which is based primarily on original interviews, and an analysis of the content of the publication itself. Ot Vinta was the central magazine of the Riga Russian language underground music scene of its time and is closely linked to the unofficial rock music subculture of the whole Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, making it a very important historical source for this time and for this music. The final conclusion is that there are no significant differences between Soviet music samizdat and Wes- tern zines. -

Travel Guide

TRAVEL GUIDE Traces of the COLD WAR PERIOD The Countries around THE BALTIC SEA Johannes Bach Rasmussen 1 Traces of the Cold War Period: Military Installations and Towns, Prisons, Partisan Bunkers Travel Guide. Traces of the Cold War Period The Countries around the Baltic Sea TemaNord 2010:574 © Nordic Council of Ministers, Copenhagen 2010 ISBN 978-92-893-2121-1 Print: Arco Grafisk A/S, Skive Layout: Eva Ahnoff, Morten Kjærgaard Maps and drawings: Arne Erik Larsen Copies: 1500 Printed on environmentally friendly paper. This publication can be ordered on www.norden.org/order. Other Nordic publications are available at www.norden.org/ publications Printed in Denmark T R 8 Y 1 K 6 S 1- AG NR. 54 The book is produced in cooperation between Øhavsmuseet and The Baltic Initiative and Network. Øhavsmuseet (The Archipelago Museum) Department Langelands Museum Jens Winthers Vej 12, 5900 Rudkøbing, Denmark. Phone: +45 63 51 63 00 E-mail: [email protected] The Baltic Initiative and Network Att. Johannes Bach Rasmussen Møllegade 20, 2200 Copenhagen N, Denmark. Phone: +45 35 36 05 59. Mobile: +45 30 25 05 59 E-mail: [email protected] Top: The Museum of the Barricades of 1991, Riga, Latvia. From the Days of the Barricades in 1991 when people in the newly independent country tried to defend key institutions from attack from Soviet military and security forces. Middle: The Anna Akhmatova Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia. Handwritten bark book with Akhmatova’s lyrics. Made by a GULAG prisoner, wife of an executed “enemy of the people”. Bottom: The Museum of Genocide Victims, Vilnius, Lithuania. -

Estonia Country Report BTI 2018

BTI 2018 Country Report Estonia This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2018. It covers the period from February 1, 2015 to January 31, 2017. The BTI assesses the transformation toward democracy and a market economy as well as the quality of political management in 129 countries. More on the BTI at http://www.bti-project.org. Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2018 Country Report — Estonia. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2018. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Contact Bertelsmann Stiftung Carl-Bertelsmann-Strasse 256 33111 Gütersloh Germany Sabine Donner Phone +49 5241 81 81501 [email protected] Hauke Hartmann Phone +49 5241 81 81389 [email protected] Robert Schwarz Phone +49 5241 81 81402 [email protected] Sabine Steinkamp Phone +49 5241 81 81507 [email protected] BTI 2018 | Estonia 3 Key Indicators Population M 1.3 HDI 0.865 GDP p.c., PPP $ 29365 Pop. growth1 % p.a. 0.1 HDI rank of 188 30 Gini Index 34.6 Life expectancy years 77.1 UN Education Index 0.899 Poverty3 % 1.2 Urban population % 67.5 Gender inequality2 0.131 Aid per capita $ - Sources (as of October 2017): The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2017 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2016. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $3.20 a day at 2011 international prices. Executive Summary Estonia has largely recovered from the economic recession of 2008 and 2009. -

The Baltic Way Towards Freedom

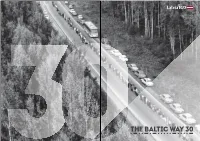

THE BALTIC The Baltic Way WAY 30 Towards Freedom At 19:00 on 23 August 1989 approximately two million people of the Baltic states joined hands forming a live, continuous chain on the road Tallinn-Rīga-Vilnius (660-670 km). Church bells sounded in the Baltic states. Mourning ribbons decorated the national flags that were banned a year ago. The participants of the Baltic Way were addressed by the leaders of Rahvarinne - the Estonian Popular Front, the Lithuanian movement Sajūdis and the Popular Front of Latvia. The following words were heard – ‘laisvė’, ‘svabadus, ‘brīvība’ (freedom). The symbols of Nazi Germany and the Communist regime of the USSR were burned in large bonfires. Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania engaged in collective action against the non-assault agreement between Hitler and Stalin of 23 August 1939 and its secret protocols or the “devil pact”. The Baltic states demanded the cessation of half-century long Soviet occupation, colonisation, russification and Photo 1 (cover photo) communist genocide. The Baltic Way became the The Baltic Way on Pleskava highway. crucial application by the Baltic states’ civil society The photo was taken from the helicopter for independence and return to Europe. It was the on 23 August 1989. first dice in the domino effect that disrupted the Photographer Aivars Liepiņš. Archive of the Latvian Institute. totalitarian regime in Eastern Europe - the first step towards regaining national independence of Latvia. © State Chancellery of Latvia, 2019 THE BALTIC WAY 30 1 2 THE BALTIC WAY 30 Photo 2 Causes and Participants of the Baltic Way on the Stone Bridge (at that time the October Bridge). -

Latvia 1988-2015: a Triumph of the Radical Nationalists

The Baltic Centre of Historical and Socially Political Studies Victor Gushchin Latvia 1988-2015: a triumph of the radical nationalists Political support of the West for Latvian radical nationalism and neo-Nazismand the import of this ideology into Latvia after the West’s victory in the Cold War. Formation of a unipolar world led by the USA, revision of the 1945 Yalta and Potsdam treaties and the 1975 Helsinki Final Act of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe as main reasons for the evolution of the Republic of Latvia of May 4th, 1990,from elimination of universal suffrage to relapse of totalitarianism: establishment of the so-called «Latvian Latvia», Russophobia, suppression of ethnic minority rights, restriction of freedom of speech and assembly, revision of the outcome of World War Two and propaganda of neo-Nazism. Riga 2017 UDK 94(474.3) “19/20” Gu 885 The book Latvia 1988-2015: a triumph of the radical nationalists» is dedicated to Latvia’s most recent history. On May 4, 1990, the Supreme Soviet (Supreme Council) of the Latvian SSR adopted the Declaration on the Restoration of Independence of the Latvian Republic without holding a national referendum, thus violating the acting Constitution. Following this up on October 15, 1991, the Supreme Soviet deprived more than a third of its own electorate Latvia 1988 - 2015: of the right to automatic citizenship. As a result, one of the most fundamental principles of a triumph of the radical nationalists democracy, universal suffrage, was eliminated. Thereafter, the Latvian parliament, periodically re-elected in conditions where a signif- icant part of country’s inhabitants lack the right to participate in elections, has been adopting Book 1.