Livro Ingles 2008.PMD

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Enrique Iglesias' “Duele El Corazon” Reaches Over 1 Billion Cumulative Streams and Over 2 Million Downloads Sold Worldwide

ENRIQUE IGLESIAS’ “DUELE EL CORAZON” REACHES OVER 1 BILLION CUMULATIVE STREAMS AND OVER 2 MILLION DOWNLOADS SOLD WORLDWIDE RECEIVES AMERICAN MUSIC AWARD FOR BEST LATIN ARTIST (New York, New York) – This past Sunday, global superstar Enrique Iglesias wins the American Music Award for Favorite Latin Artist – the eighth in his career and the most by any artist in this category. The award comes on the heels of a whirlwind year for Enrique. His latest single, “DUELE EL CORAZON” has shattered records across the globe. The track (click here to listen) spent 14 weeks at #1 on the Hot Latin Songs chart, held the #1 spot on the Latin Pop Songs chart for 10 weeks and has over 1 billion cumulative streams and over 2 million tracks sold worldwide. The track also marks Enrique’s 14th #1 on the Dance Club Play chart, the most by any male artist. He also holds the record for the most #1 debuts on Billboard’s Latin Airplay chart. In addition to his recent AMA win, Enrique also took home 5 awards at this year’s Latin American Music Awards for Artist of the Year, Favorite Male Pop/Rock Artist and Favorite Song of the Year, Favorite Song Pop/Rock and Favorite Collaboration for “DUELE EL CORAZON” ft. Wisin. Earlier this month, Enrique went to France to receive the NRJ Award of Honor. For the past two years, Enrique has been touring the world on his SEX AND LOVE Tour which will culminate in Prague, Czech Republic on December 18th. Remaining 2016 Tour Dates Nov. -

Gabinete Da Senadora Soraya Thronicke

SENADO FEDERAL EMENDAS Apresentadas perante a Mesa do Senado Federal ao Projeto de Lei n° 4203, de 2020, que "Altera a Lei nº 6.088, de 16 de julho de 1974, para incluir as bacias hidrográficas dos estados de Minas Gerais e de Roraima na área de atuação da Companhia de Desenvolvimento do Vale do São Francisco (CODEVASF)." PARLAMENTARES EMENDAS NºS Senadora Rose de Freitas (PODEMOS/ES) 001 Senador Zequinha Marinho (PSC/PA) 002 Senador Fabiano Contarato (REDE/ES) 003 Senador Eduardo Braga (MDB/AM) 004 Senador Jaques Wagner (PT/BA) 005 Senadora Soraya Thronicke (PSL/MS) 006 Senadora Zenaide Maia (PROS/RN) 007 TOTAL DE EMENDAS: 7 Página da matéria PL 4203/2020 00001 EMENDA Nº - PLEN (ao PL nº 4.203, de 2020) Dê-se ao art. 1º do Projeto de Lei nº 4.203, de 2020, a seguinte redação: “Art. 1º O caput do art. 2º da Lei nº 6.088, de 16 de julho de 1974, passa a vigorar com a seguinte redação: ‘Art. 2º A Codevasf terá sede e foro no Distrito Federal e atuação nas bacias hidrográficas dos rios São Francisco, Parnaíba, Itapecuru, Mearim, Vaza-Barris, Paraíba, Mundaú, Jequiá, Tocantins, Munim, Gurupi, Turiaçu, Pericumã, Una, Real, Itapicuru, Paraguaçu, Araguari (AP), Araguari (MG), Jequitinhonha, Mucuri e Pardo, nos Estados de Alagoas, do Amapá, da Bahia, do Ceará, de Goiás, do Maranhão, de Mato Grosso, de Minas Gerais, do Pará, de Pernambuco, do Piauí, de Sergipe e do Tocantins e no Distrito Federal, bem como nas demais bacias hidrográficas e litorâneas dos Estados de Alagoas, do Amapá, da Bahia, do Ceará, do Espírito Santo, de Goiás, do Maranhão, de Minas Gerais, da Paraíba, de Pernambuco, do Piauí, do Rio Grande do Norte, de Roraima e de Sergipe, e poderá, se houver prévia dotação orçamentária, instalar e manter no País órgãos e setores de operação e representação.’ (NR)” JUSTIFICAÇÃO A área de atuação da Companhia de Desenvolvimento do Vale do São Francisco (CODEVASF) vem sendo constantemente expandida. -

Spanish NACH INTERPRET

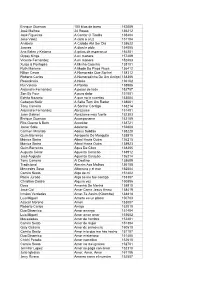

Enrique Guzman 100 kilos de barro 152009 José Malhoa 24 Rosas 136212 José Figueiras A Cantar O Tirolês 138404 Jose Velez A cara o cruz 151104 Anabela A Cidade Até Ser Dia 138622 Juanes A dios le pido 154005 Ana Belen y Ketama A gritos de esperanza 154201 Gypsy Kings A mi manera 157409 Vicente Fernandez A mi manera 152403 Xutos & Pontapés A Minha Casinha 138101 Ruth Marlene A Moda Do Pisca Pisca 136412 Nilton Cesar A Namorada Que Sonhei 138312 Roberto Carlos A Namoradinha De Um Amigo M138306 Resistência A Noite 136102 Rui Veloso A Paixão 138906 Alejandro Fernandez A pesar de todo 152707 Son By Four A puro dolor 151001 Ednita Nazario A que no le cuentas 153004 Cabeças NoAr A Seita Tem Um Radar 138601 Tony Carreira A Sonhar Contigo 138214 Alejandro Fernandez Abrazame 151401 Juan Gabriel Abrazame muy fuerte 152303 Enrique Guzman Acompaname 152109 Rita Guerra & Beto Acreditar 138721 Javier Solis Adelante 152808 Carmen Miranda Adeus Solidão 138220 Quim Barreiros Aeroporto De Mosquito 138510 Mónica Sintra Afinal Havia Outra 136215 Mónica Sintra Afinal Havia Outra 138923 Quim Barreiros Água De Côco 138205 Augusto César Aguenta Coração 138912 José Augusto Aguenta Coração 136214 Tony Carreira Ai Destino 138609 Tradicional Alecrim Aos Molhos 136108 Mercedes Sosa Alfonsina y el mar 152504 Camilo Sesto Algo de mi 151402 Rocio Jurado Algo se me fue contigo 153307 Christian Castro Alguna vez 150806 Doce Amanhã De Manhã 138910 José Cid Amar Como Jesus Amou 138419 Irmãos Verdades Amar-Te Assim (Kizomba) 138818 Luis Miguel Amarte es un placer 150703 Azucar -

General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade Accord

GENERAL AGREEMENT ON TARIFFS AND TRADE MIN(86)/INF/3 ACCORD GENERAL SUR LES TARIFS DOUANIERS ET LE COMMERCE 17 September 1986 ACUERDO GENERAL SOBRE ARANCELES ADUANEROS Y COMERCIO Limited Distribution CONTRACTING PARTIES PARTIES CONTRACTANTES PARTES CONTRATANTIS Session at Ministerial Session à l'échelon Periodo de sesiones a nivel Level ministériel ministerial 15-19 September 1986 15-19 septembre 1986 15-19 setiembre 1986 LIST OF REPRESENTATIVES LISTE DES REPRESENTANTS LISTA DE REPRESENTANTES Chairman: S.E. Sr. Enrique Iglesias Président; Ministro de Relaciones Exteriores Présidente; de la Republica Oriental del Uruguay ARGENTINA Représentantes Lie. Dante Caputo Ministro de Relaciones Exteriores y Culto » Dr. Juan V. Sourrouille Ministro de Economia Dr. Roberto Lavagna Secretario de Industria y Comercio Exterior Ing. Lucio Reca Secretario de Agricultura, Ganaderïa y Pesca Dr. Bernardo Grinspun Secretario de Planificaciôn Dr. Adolfo Canitrot Secretario de Coordinaciôn Econômica 86-1560 MIN(86)/INF/3 Page 2 ARGENTINA (cont) Représentantes (cont) S.E. Sr. Jorge Romero Embajador Subsecretario de Relaciones Internacionales Econômicas Lie. Guillermo Campbell Subsecretario de Intercambio Comercial Dr. Marcelo Kiguel Vicepresidente del Banco Central de la Republica Argentina S.E. Leopoldo Tettamanti Embaj ador Représentante Permanante ante la Oficina de las Naciones Unidas en Ginebra S.E. Carlos H. Perette Embajador Représentante Permanente de la Republica Argentina ante la Republica Oriental del Uruguay S.E. Ricardo Campero Embaj ador Représentante Permanente de la Republica Argentina ante la ALADI Sr. Pablo Quiroga Secretario Ejecutivo del Comité de Politicas de Exportaciones Dr. Jorge Cort Présidente de la Junta Nacional de Granos Sr. Emilio Ramôn Pardo Ministro Plenipotenciario Director de Relaciones Econômicas Multilatérales del Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores y Culto Sr. -

Parecer Nº , De 2020 Sf/20989.09666-21

Gabinete do Senador Angelo Coronel PARECER Nº , DE 2020 SF/20989.09666-21 De PLENÁRIO, sobre o Projeto de Lei nº 2.630, de 2020, do Senador Alessandro Vieira, que institui a Lei Brasileira de Liberdade, Responsabilidade e Transparência na Internet. RELATOR: Senador ANGELO CORONEL I – RELATÓRIO Vem ao Plenário do Senado Federal, para apreciação, nos termos regimentais, o Projeto de Lei nº 2.630, de 2020, do Senador Alessandro Vieira, que institui a Lei Brasileira de Liberdade, Responsabilidade e Transparência na Internet A proposição é composta por 31 artigos, divididos em seis capítulos. O Capítulo I trata das disposições preliminares, e, em essência, determina que: a) a lei estabelece diretrizes e mecanismos de transparência para aplicações de redes sociais e de serviços de mensageria privada na internet, para desestimular abusos ou manipulação com potencial para causar danos (art. 1º); b) a lei não se aplicará a provedores de aplicação com menos de dois milhões de usuários (art. 1º, § 1º); Praça dos Três Poderes | Senado Federal | Anexo 2 | Ala Senador Afonso Arinos | Gabinete 03 | CEP: 70165-900 | Brasília-DF Gabinete do Senador Angelo Coronel c) a lei levará em consideração os dispositivos presentes na Lei nº 12.965, de 23 de abril de 2014 (Marco Civil da Internet – MCI), e na Lei nº 13.709, de 14 de agosto de 2018 (Lei Geral de Proteção dos Dados Pessoais – SF/20989.09666-21 LGPD) (art. 2º). Ainda no Capítulo I, são estabelecidas algumas definições (art. 4º), merecendo destaque as seguintes: d) desinformação: conteúdo, em parte ou -

Medida Provisória N° 1010, De 2020

Atividade Legislativa Medida Provisória n° 1010, de 2020 Autoria: Presidência da República Iniciativa: Ementa: Isenta os consumidores dos Municípios do Estado do Amapá abrangidos pelo estado de calamidade pública do pagamento da fatura de energia elétrica referente aos últimos trinta dias e altera a Lei nº 10.438, de 26 de abril de 2002. Explicação da Ementa: Isenção do pagamento da fatura de energia elétrica aos consumidores do Estado do Amapá, não se aplicando a débitos pretéritos, parcelamentos ou outras cobranças incluídas nas faturas elegíveis, se não relacionados à cobrança pelo consumo registrado no mês de competência. Assunto: Jurídico - Direito do Consumidor Data de Leitura: - Tramitação encerrada Decisão: Aprovada na forma de Projeto de Lei Último local: 28/06/2021 - Secretaria de Expediente Destino: À sanção Último estado: 27/04/2021 - TRANSFORMADA EM NORMA JURÍDICA COM VETO PARCIAL Matérias Relacionadas: Requerimento nº 1270 de 2021 Requerimento nº 1285 de 2021 Veto nº 00017 de 2021 Despacho: Relatoria: 19/03/2021 PLEN - (Plenário do Senado Federal) Decisão da Presidência Relator(es): Senador Davi Alcolumbre (encerrado em 30/03/2021 - Ao Plenário, nos termos do Ato da Comissão Diretora nº 7, Deliberação da matéria) (SF-PLEN) Plenário do Senado Federal TRAMITAÇÃO 30/06/2021 SF-SEXPE - Secretaria de Expediente Ação: Remetido Ofício CN nº 185, de 30/06/21, ao Senhor Presidente da Câmara dos Deputados, comunicando o término do prazo estabelecido no § 2º do art. 11 da Resolução nº 1, de 2002-CN, e no § 11 do art. 62 da Constituição Federal, em 25 de junho de 2021, para edição do decreto legislativo destinado a regular as relações jurídicas decorrentes da Medida Provisória nº 1010, de 2020, que teve seu término de vigência ocorrido em 27 de abril de 2021 com sua conversão na Lei nº14.146, de 2021, sancionada no dia 26 do mesmo mês e ano. -

Mood Music Programs

MOOD MUSIC PROGRAMS MOOD: 2 Pop Adult Contemporary Hot FM ‡ Current Adult Contemporary Hits Hot Adult Contemporary Hits Sample Artists: Andy Grammer, Taylor Swift, Echosmith, Ed Sample Artists: Selena Gomez, Maroon 5, Leona Lewis, Sheeran, Hozier, Colbie Caillat, Sam Hunt, Kelly Clarkson, X George Ezra, Vance Joy, Jason Derulo, Train, Phillip Phillips, Ambassadors, KT Tunstall Daniel Powter, Andrew McMahon in the Wilderness Metro ‡ Be-Tween Chic Metropolitan Blend Kid-friendly, Modern Pop Hits Sample Artists: Roxy Music, Goldfrapp, Charlotte Gainsbourg, Sample Artists: Zendaya, Justin Bieber, Bella Thorne, Cody Hercules & Love Affair, Grace Jones, Carla Bruni, Flight Simpson, Shane Harper, Austin Mahone, One Direction, Facilities, Chromatics, Saint Etienne, Roisin Murphy Bridgit Mendler, Carrie Underwood, China Anne McClain Pop Style Cashmere ‡ Youthful Pop Hits Warm cosmopolitan vocals Sample Artists: Taylor Swift, Justin Bieber, Kelly Clarkson, Sample Artists: The Bird and The Bee, Priscilla Ahn, Jamie Matt Wertz, Katy Perry, Carrie Underwood, Selena Gomez, Woon, Coldplay, Kaskade Phillip Phillips, Andy Grammer, Carly Rae Jepsen Divas Reflections ‡ Dynamic female vocals Mature Pop and classic Jazz vocals Sample Artists: Beyonce, Chaka Khan, Jennifer Hudson, Tina Sample Artists: Ella Fitzgerald, Connie Evingson, Elivs Turner, Paloma Faith, Mary J. Blige, Donna Summer, En Vogue, Costello, Norah Jones, Kurt Elling, Aretha Franklin, Michael Emeli Sande, Etta James, Christina Aguilera Bublé, Mary J. Blige, Sting, Sachal Vasandani FM1 ‡ Shine -

Senado Federal Parecer (Sf) Nº 80, De 2017

SENADO FEDERAL PARECER (SF) Nº 80, DE 2017 Da COMISSÃO DE CONSTITUIÇÃO, JUSTIÇA E CIDADANIA, sobre o processo Projeto de Lei do Senado n°160, de 2013, do Senador João Capiberibe, que Prever a destinação de no mínimo cinco por cento dos recursos do Fundo Partidário para promoção da participação política dos afrodescendentes. PRESIDENTE: Senador Edison Lobão RELATOR: Senador Randolfe Rodrigues RELATOR ADHOC: Senador José Pimentel 09 de Agosto de 2017 2 SENADO FEDERAL Gabinete do Senador Randolfe Rodrigues PARECER Nº , DE 2016 Da COMISSÃO DE CONSTITUIÇÃO, JUSTIÇA E CIDADANIA, em decisão terminativa, sobre o Projeto de Lei do Senado (PLS) nº 160, de 2013, do Senador João Capiberibe, que prevê a destinação de no mínimo cinco por cento dos recursos do Fundo Partidário para promoção da SF/16213.99686-25 participação política dos afrodescendentes. Relator: Senador RANDOLFE RODRIGUES Relator "Ad hoc": Senador JOSÉ PIMENTEL I – RELATÓRIO Vem ao exame desta Comissão o Projeto de Lei do Senado (PLS) nº 160, de 2013, do Senador João Capiberibe, que prevê a destinação de no mínimo cinco por cento dos recursos do Fundo Partidário para promoção da participação política dos afrodescendentes. O projeto é constituído por dois artigos. O art. 1º altera o art. 44 da Lei nº 9.096, de 19 de setembro de 1995, que dispõe sobre partidos políticos, regulamenta os arts. 17 e 14, § 3º, inciso V, da Constituição Federal, para determinar que os partidos políticos apliquem recursos oriundos do Fundo Partidário na criação e manutenção de programas de promoção e difusão da participação política dos afrodescendentes, conforme percentual que será fixado pelo órgão nacional de direção partidária, observado o mínimo de cinco por cento do total. -

Ficha Técnica Jogo a Jogo, 1992 - 2011

FICHA TÉCNICA JOGO A JOGO, 1992 - 2011 1992 Palmeiras: Velloso (Marcos), Gustavo, Cláudio, Cléber e Júnior; Galeano, Amaral (Ósio), Marquinhos (Flávio Conceição) e Elivélton; Rivaldo (Chris) e Reinaldo. Técnico: Vander- 16/Maio/1992 Palmeiras 4x0 Guaratinguetá-SP lei Luxemburgo. Amistoso Local: Dario Rodrigues Leite, Guaratinguetá-SP 11/Junho/1996 Palmeiras 1x1 Botafogo-RJ Árbitro: Osvaldo dos Santos Ramos Amistoso Gols: Toninho, Márcio, Edu Marangon, Biro Local: Maracanã, Rio de Janeiro-RJ Guaratinguetá-SP: Rubens (Maurílio), Mineiro, Veras, César e Ademir (Paulo Vargas); Árbitro: Cláudio Garcia Brás, Sérgio Moráles (Betinho) e Maizena; Marco Antônio (Tom), Carlos Alberto Gols: Mauricinho (BOT); Chris (PAL) (Américo) e Tiziu. Técnico: Benê Ramos. Botafogo: Carlão, Jefferson, Wilson Gottardo, Gonçalves e André Silva; Souza, Moisés Palmeiras: Marcos, Odair (Marques), Toninho, Tonhão (Alexandre Rosa) e Biro; César (Julinho), Dauri (Marcelo Alves) e Bentinho (Hugo); Mauricinho e Donizete. Técnico: Sampaio, Daniel (Galeano) e Edu Marangon; Betinho, Márcio e Paulo Sérgio (César Ricardo Barreto. Mendes). Técnico: Nelsinho Baptista Palmeiras: Velloso (Marcos), Gustavo (Chris), Roque Júnior, Cléber (Sandro) e Júnior (Djalminha); Galeano (Rodrigo Taddei), Amaral (Emanuel), Flávio Conceição e Elivél- 1996 ton; Rivaldo (Dênis) e Reinaldo (Marquinhos). Técnico: Vanderlei Luxemburgo. 30/Março/1996 Palmeiras 4x0 Xv de Jaú-SP 17/Agosto/1996 Palmeiras 5x0 Coritiba-PR Campeonato Paulista Campeonato Brasileiro Local: Palestra Itália Local: Palestra Itália Árbitro: Alfredo dos Santos Loebeling Árbitro: Carlos Eugênio Simon Gols: Alex Alves, Cláudio, Djalminha, Cris Gols: Luizão (3), Djalminha, Rincón Palmeiras: Velloso (Marcos), Gustavo (Ósio), Sandro, Cláudio e Júnior; Amaral, Flávio Palmeiras: Marcos, Cafu, Cláudio (Sandro), Cléber e Júnior (Fernando Diniz); Galeano, Conceição, Rivaldo (Paulo Isidoro) e Djalminha; Müller (Chris) e Alex Alves. -

Communiqué De Presse Maroc Telecom Lance Le Forfait Universal

Communiqué de presse Rabat, le 03 décembre 2010 Maroc Telecom lance le Forfait Universal Music 60 minutes de communication, 300 SMS / MMS, l’accès exclusif et illimité un catalogue riche et inédit de vidéos clips Universal Music et aux 4 chaînes de télévision MTV, le tout à 99 DH, c’est le nouveau Forfait de Maroc Telecom pour les jeunes. Le Forfait Universal Music est le fruit d’un partenariat entre Maroc Telecom, Universal Music, leader mondial de la musique et pionnier de la distribution musicale numérique et MTV (Music Television), chaîne de télévision spécialisée dans la diffusion des vidéo-clips musicaux. Visionner sur leur mobile les contenus vidéos clips sans cesse renouvelés et enrichis du catalogue d’Universal Music, accéder aux 4 chaînes du bouquet MTV, rester en contact avec leurs parents et leurs proches grâce à 60 minutes de communications valables vers toutes les destinations nationales et internationales** et à 300 SMS / MMS vers tous les opérateurs nationaux, c’est tout cela à la fois que Maroc Telecom offre aux jeunes en un seul forfait, pour 99 DH seulement. Pour leur permettre de profiter pleinement du forfait Universal Music Mobile, Maroc Telecom met à leur disposition une large gamme de terminaux à partir de 0 DH*. Ils pourront également participer à des animations et des jeux concours dédiés et bénéficier gratuitement des services de transfert et de réception d’argent sur mobile, Mobicash. L’offre Forfait Universal Music, bâtie sur des savoir-faire complémentaires, reflète la volonté de Maroc Telecom de satisfaire toujours mieux les attentes d’une clientèle jeune, avide de communication et de nouveaux contenus mais soucieuse de maîtriser son budget. -

Prefeitura Municipal De Matinhos Estado Do Paraná

PREFEITURA MUNICIPAL DE MATINHOS ESTADO DO PARANÁ Edital nº 047/2011 A Prefeitura Municipal de Matinhos, através da Comissão Especial de Seleção de Pessoal, nomeada pelo Decreto n 0 418/2011, no uso de suas atribuições legais, mediante as condições estipuladas neste Edital e seus Anexos e tendo em vista o contrato celebrado com a Fundação da Universidade Federal do Paraná para o Desenvolvimento da Ciência, da Tecnologia e da Cultura – FUNPAR e a Universidade Federal do Paraná – UFPR, RESOLVE: 1. HOMOLOGAR as inscrições dos candidatos ao Concurso Público previsto nos Editais nº. 039/2011, 040/2011, 041/2011,042/2011 conferidas pelo Núcleo de Concursos da Universidade Federal do Paraná, conforme relação anexa. 2. INFORMAR que, a partir de 19 de setembro de 2011 , o candidato deverá acessar o site www.nc.ufpr.br e imprimir o seu comprovante de ensalamento , onde estarão indicados também o local e o horário de realização das provas. Matinhos, 14 de setembro de 2011. _____________________________ EDUARDO ANTONIO DALMORA Prefeito ______________________________________ NIUCELIA VIECK Presidente da Comissão Especial do Concurso PREFEITURA MUNICIPAL DE MATINHOS ESTADO DO PARANÁ ANEXO ÚNICO – Relação das Inscrições Homologadas RELAÇÃO DAS INSCRIÇÕES HOMOLOGADAS PROTOCOLO NOME CARGO 02108 ABEL BORBA NETO AGENTE ADMINISTRATIVO 07781 ABNER FELICIANO CAMARGO TÉCNICO ADMINISTRATIVO 09463 ACTYRENE OLIVEIRA MAGALHAES SOARES FISCAL DO MEIO AMBIENTE 07903 ADAILTON DOMINGUES COCATTO DE LIMA TÉCNICO ADMINISTRATIVO 06598 ADALBERTO CORDEIRO ROCHA ADVOGADO 04105 -

Inteiro Teor

REPÚBLICA FEDERATIVA DO BRASIL DIÁRIO DA CÂMARA DOS DEPUTADOS ANO LXVIII - Nº 107 - SEXTA-FEIRA, 21 DE JUNHO DE 2013 - BRASÍLIA-DF MESA DA CÂMARA DOS DEPUTADOS (Biênio 2013/2014) PRESIDENTE HENRIQUE EDUARDO ALVES (PMDB-RN) 1º VICE-PRESIDENTE ANDRE VARGAS (PT-PR) 2º VICE-PRESIDENTE FÁBIO FARIA (PSD-RN) 1º SECRETÁRIO MARCIO BITTAR (PSDB-AC) 2º SECRETÁRIO SIMÃO SESSIM (PP-RJ) 3º SECRETÁRIO MAURÍCIO QUINTELLA LESSA (PR-AL) 4º SECRETÁRIO BIFFI (PT-MS) 1º SUPLENTE GONZAGA PATRIOTA (PSB-PE) 2º SUPLENTE WOLNEY QUEIROZ (PDT-PE) 3º SUPLENTE VITOR PENIDO (DEM-MG) 4º SUPLENTE TAKAYAMA (PSC-PR) CONGRESSO NACIONAL Faço saber que o Congresso Nacional aprovou, e eu, Renan Calheiros, Presidente do Senado Fede- ral, nos termos do parágrafo único do art. 52 do Regimento Comum e do inciso XXVIII do art. 48 do Regimento Interno do Senado Federal, promulgo o seguinte DECRETO LEGISLATIVO Nº 247, DE 2013 Aprova o ato que renova a permissão outorgada à LITORAL RADIODIFUSÃO LTDA. para explorar serviço de radiodifusão sonora em frequência modulada na cidade de Ar- raial do Cabo, Estado do Rio de Janeiro. O Congresso Nacional decreta: Art. 1º Fica aprovado o ato a que se refere a Portaria nº 345, de 15 de abril de 2010, que renova por 10 (dez) anos, a partir de 23 de setembro de 2008, a permissão outorgada à Litoral Radiodifusão Ltda. para ex- plorar, sem direito de exclusividade, serviço de radiodifusão sonora em frequência modulada na cidade de Arraial do Cabo, Estado do Rio de Janeiro. Art. 2º Este Decreto Legislativo entra em vigor na data de sua publicação.