Uvic Thesis Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Core 1..48 Committee (PRISM::Advent3b2 10.50)

House of Commons CANADA Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage CHPC Ï NUMBER 033 Ï 2nd SESSION Ï 39th PARLIAMENT EVIDENCE Tuesday, June 3, 2008 Chair Mr. Gary Schellenberger Also available on the Parliament of Canada Web Site at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 1 Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage Tuesday, June 3, 2008 Ï (1535) year, the concert was aired for the first time on Radio 2's Canada [English] Live as a result of the opening up of broadcast opportunities for more than classical music. We welcome that change. The Chair (Mr. Gary Schellenberger (Perth—Wellington, CPC)): Good afternoon, everyone. Welcome to meeting number 33 of the Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage. ln 1988, CBC Radio producers of the now defunct The Entertainers approached me, in my role as artistic director of Pursuant to Standing Order 108(2), we are undertaking a study on Toronto's Harbourfront Centre summer concert season, regarding an the dismantling of the CBC Radio Orchestra, on CBC/Radio- opportunity to record elements of the then-just-Iaunched WOMAD Canada's commitment to classical music, and the changes to CBC —Worlds of Music Arts and Dance—festival. It was a revelation. Radio 2. The partnership involved a model whereby a $25,000 blanket fee I welcome all our witnesses here today. Our witnesses are Derek would give CBC the right to record performances. Thirty-three Andrews, president of the Toronto Blues Society; Dominic Lloyd, concerts were recorded that year, and thus began a partnership that artistic director of the West End Cultural Centre; Katherine Carleton, involved many further concert recordings over the years. -

A Canada Fit for Children

A CANADA FIT FOR CHILDREN Canada’s follow-up to the United Nations General Assembly Special Session on Children, dated April 2004. 1 Aussi disponible en français sous le titre Un Canada digne des enfants April 2004 © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2004 Paper Catalogue No. SD13-4/2004E ISBN 0-662-36985-8 PDF Catalogue No. SD13-4/2004E-PDF ISBN 0-662-36991-2 HTML Catalogue No. SD13-4/2004E-HTML ISBN 0-662-36992-0 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page A message from the Prime Minister. 5 A message from the Minister of Health and the Minister of Social Development . 7 A message from Senator Landon Pearson . 9 A message from the young people of CEERT . 11 A Canada Fit for Children I. Preface . 13 II. Declaration . 15 III. Toward a Common Canadian Vision for Children . 19 IV. Plan of Action. 37 A. Creating a Canada and a World Fit for Children. 37 B. Goals, Strategies and Actions for Canada . 41 1. Supporting Families and Strengthening Communities . 41 2. Promoting Healthy Lives. 50 3. Protecting from Harm . 64 4. Promoting Education and Learning. 78 C. Building Momentum . 87 A Call to Action . 87 Partnerships and Participation . 87 Keeping on Track . 90 V. Government of Canada Investments in and Commitments to Children. 93 A. For Canada's Children. 93 B. For the World's Children. 113 3 4 A message from the Prime Minister The children of today constitute the largest generation of young people the world has ever known. And the world will be profoundly affected by their actions and decisions – not only in the years to come, but even right now. -

BC's Music Sector

BC’s Music Sector FROM ADVERSITY TO OPPORTUNITY www.MusicCanada.com /MusicCanada @Music_Canada BC’S MUSIC SECTOR: FROM ADVERSITY TO OPPORTUNITY A roadmap to reclaim BC’s proud music heritage and ignite its potential as a cultural and economic driver. FORWARD | MICHAEL BUBLÉ It’s never been easy for artists to get a start in We all have a role to play. Record labels and music. But it’s probably never been tougher other music businesses need to do a better than it is right now. job. Consumers have to rethink how they consume. Governments at all levels have to My story began like so many other kids recalibrate their involvement with music. And with a dream. I was inspired by some of successful artists have to speak up. the greatest singers – Ella Fitzgerald, Tony Bennett and Frank Sinatra – listening to my We all have to pull together and take action. grandfather’s record collection while growing up in Burnaby. I progressed from talent I am proud of the fact that BC gave me a competitions, to regular shows at local music start in a career that has given me more venues, to a wedding gig that would put me than I could have ever imagined. After in the right room with the right people – the touring around the world, I am always right BC people. grateful to come home to BC where I am raising my family. I want young artists to When I look back, I realize how lucky I was. have the same opportunities I had without There was a thriving music ecosystem in BC having to move elsewhere. -

Security Coordinator

STEVE SUMMERVILLE Curriculum Vitae April 2021 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents ...................................................................... 2 Steven Summerville – Contact Information .............................. 3 Professional Background ......................................................... 3 Education ................................................................................ 10 Continuing Education ............................................................. 11 Associations ........................................................................... 16 Awards .................................................................................... 16 Crowd Control Project Management ....................................... 18 Special Events Management................................................... 19 Project Participation ............................................................... 25 Private Consulting .................................................................. 37 Media Presentations ............................................................... 68 Expert Witness Recognition ................................................... 85 April 2021 2 Steven Summerville – Contact Information STAY SAFE Instructional Programs. (SSIP) 3 Holmes Crescent Ajax, Ontario. L1T 3R6 Cell: (416)-318-8299 Email: [email protected] [email protected] Website: https://staysafeip.com/ Professional Background CANADIAN NATIONAL EXHIBITION ASSOCIATION (CNE). – Toronto, Ontario. May 2016 to present Security Coordinator. -

Of Analogue: Access to Cbc/Radio-Canada Television Programming in an Era of Digital Delivery

THE END(S) OF ANALOGUE: ACCESS TO CBC/RADIO-CANADA TELEVISION PROGRAMMING IN AN ERA OF DIGITAL DELIVERY by Steven James May Master of Arts, Ryerson University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2008 Bachelor of Applied Arts (Honours), Ryerson University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 1999 Bachelor of Administrative Studies (Honours), Trent University, Peterborough, Ontario, Canada, 1997 A dissertation presented to Ryerson University and York University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Program of Communication and Culture Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2017 © Steven James May, 2017 AUTHOR'S DECLARATION FOR ELECTRONIC SUBMISSION OF A DISSERTATION I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this dissertation. This is a true copy of the dissertation, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this dissertation to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this dissertation by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my dissertation may be made electronically available to the public. ii ABSTRACT The End(s) of Analogue: Access to CBC/Radio-Canada Television Programming in an Era of Digital Delivery Steven James May Doctor of Philosophy in the Program of Communication and Culture Ryerson University and York University, 2017 This dissertation -

Rev-Radio One F 09

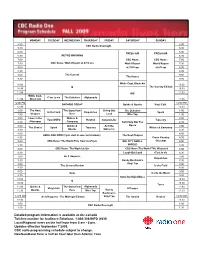

MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 5:00 5:00 CBC Radio Overnight 5:30 5:30 6:00 6:00 FRESH AIR FRESH AIR 6:30 METRO MORNING 6:30 7:00 CBC News: CBC News: 7:00 7:30 CBC News: World Report at 6/7/8 am World Report World Report 7:30 8:00 at 7/8/9 am at 8/9 am 8:00 8:30 8:30 9:00 The Current 9:00 The House 9:30 9:30 10:00 White Coat, Black Art 10:00 Q The Sunday Edition 10:30 10:30 11:00 GO! 11:00 White Coat, C'est la vie The Debaters Afghanada 11:30 Black Art 11:30 12:00 PM 12:00 PM ONTARIO TODAY Quirks & Quarks Vinyl Café 12:30 12:30 1:00 The Next The Story from Living Out The Debaters 1:00 In the Field Dispatches Spark 1:30 Chapter Here Loud Wire Tap 1:30 2:00 Ideas in the Writers & 2:00 Your DNTO Rewind Canada Live Tapestry 2:30 Afternoon Company Definitely Not The 2:30 3:00 Quirks & And the Opera 3:00 The Choice Spark Tapestry Writers & Company 3:30 Quarks Winner Is 3:30 4:00 4:00 HERE AND NOW (3 pm start in selected markets) The Next Chapter 4:30 Cross Country 4:30 5:00 CBC News: The World This Hour at 4/5 pm BIG CITY SMALL Checkup 5:00 5:30 WORLD 5:30 6:00 CBC News: The World at Six CBC News:The World This Weekend 6:00 6:30 Laugh Out Loud C'est la vie 6:30 7:00 As It Happens 7:00 Dispatches 7:30 Randy Bachman's 7:30 8:00 Vinyl Tap 8:00 The Current Review In the Field 8:30 8:30 9:00 9:00 Ideas Inside the Music 9:30 9:30 Saturday Night Blues 10:00 10:00 Q 10:30 10:30 Tonic 11:00 Quirks & The Story from Afghanada 11:00 Vinyl Café A Propos 11:30 Quarks Here Wire Tap Randy 11:30 Bachman's 12:00 AM As It Happens - The Midnight Edition Vinyl Tap The Strand Rewind 12:00 AM 12:30 12:30 1:00 1:00 CBC Radio Overnight 1:30 1:30 Detailed program information is available at cbc.ca/radio Toll-free number for Audience Relations: 1-866-306-INFO (4636) Local/Regional news on the half hour from 6 am - 6 pm. -

Rev-Radio One October 26 2009 Changes

Schedule begins October 26, 2009 and detailed program information is available at cbc.ca/radio. Newfoundland Time is half an hour later than Atlantic Time. MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 5:00 BBC Witness & World Business Asian Pacific Heart and Soul World Business 5:00 5:30 BBC All in the Mind One Planet Health Check 5:30 6:00 6:00 6:30 METRO MORNING 6:30 FRESH AIR FRESH AIR 7:00 7:00 CBC News: World CBC News: World CBC News: World Report at 5/6/7/8 am 7:30 Report 6/7/8/9 Report 6/7/8/9 7:30 8:00 8:00 8:30 8:30 9:00 The Current 9:00 The House 9:30 9:30 10:00 White Coat, Black Art 10:00 Q The Sunday 10:30 Edition 10:30 11:00 11:00 White Coat, GO! C'est la vie The Debaters Afghanada Black Art (3:30 NT) (3:30 NT) (3:30 NT) 11:30 (3:30 NT) 11:30 12:00 PM 12:00 PM ONTARIO TODAY Quirks & Quarks Vinyl Café 12:30 12:30 The Next The Story Living Out Spark (4PT) 1:00 In the Field Dispatches The Debaters 1:00 1:30 Chapter from Here Loud Wire Tap 1:30 2:00 Ideas in the Writers & Tapestry 2:00 Your DNTO Rewind Canada Live 2:30 Afternoon Company (3 PT, 4 MT) 2:30 Definitely Not The Writers & 3:00 Quirks & And the Winner Opera 3:00 The Choice Spark Tapestry Company Quarks Is 3:30 (5PT/MT/CT) 3:30 4:00 4:00 HERE AND NOW (3 pm start in selected markets) The Next Chapter Cross Country 4:30 Checkup 4:30 5:00 CBC News: The World This Hour at 4/5 pm BIG CITY SMALL (1 PT, 2 MT, 3 CT, 5:00 5 AT) 5:30 WORLD 5:30 6:00 CBC News: The World at Six CBC News:The World This Weekend (7 AT) 6:00 C'est la vie (7:30 Laugh Out Loud 6:30 AT) 6:30 -

Policy Perspectives on First Nations Issues

Policy Perspectives on First Nations Issues A compilation of essays by Master’s students in the School of Policy Studies, Queen’s University November, 2017 CONTENTS Introduction iv Territorial Formula Financing in the Context of First Nations Governments Don Couturier 7 Canada’s First Nations Child Welfare Crisis: A Summary and Analysis of Contributing Factors and Recommendations for Nation-Wide Improvements Davina Dixon 29 Indigenous Child and Family Services: An In-Depth Review Amanjit Kaur Garcha 53 A Life Worth Living: Life Promotion for Indigenous Peoples on Reserve Ashley Keyes 73 Reconciliation with Indigenous People Through Business and Opportunity Kristen Sara Loft 93 First Nations Education: Increasing First Nations PSE Attainment Taylor Matchett 111 Indigenous Affairs Third-Party Policy – Can it be Improved? Vaughn Sunday 153 Raising literacy in the First Nations’ Adult Population in the Context of Labour Market Participation Anna Trankovskaya 161 INTRODUCTION The papers in Policy Perspectives on First Nation Issues provide a unique and timely snapshot of some of the most pressing policy issues facing Indigenous peoples in Canada, the Government of Canada and all Canadians. Written as part of the Masters of Public Administration (MPA) or the Professional MPA (PMPA) at the School of Policy Studies, Queen’s University, the student authors conducted in-depth research, going far beyond their course requirements. Most of the papers were written for a Directed Reading Course; one paper was written for a Masters Research Project; and one was written out of interest in the issue. The papers were supervised by Don Drummond and Bob Watts with support by Dr. -

![Annual Report 2009-2010 [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2977/annual-report-2009-2010-pdf-4012977.webp)

Annual Report 2009-2010 [PDF]

THE OLD RULES NO LONGER APPLY: RESHAPING CANADIAN PUBLIC BROADCASTING CBC | RADIO-CANADA ANNUAL REPORT 2009–2010 PROGRAMMING THE FINANCIALS IN SUCCESSES AN UNCERTAIN TIME ENGLISH SERVICES THE CHALLENGE ■■ CBC■Radio■One■and■CBC■Radio■2■achieved■a■ ■■ CBC■|■Radio-Canada’s■net■loss■of■$58.3■million■in■ combined■national■audience■share■–■13.8■per■cent■ 2009-2010■is■primarily■explained■by■weak■advertising■ (Fall■survey,■Canadians■12■years■of■age■and■older),■ revenues■that■were■unable■to■compensate■for■ with■CBC■Radio■One■matching■its■all-time■high■of■■ programming■cost■increases. 11.1■per■cent. ■■ The■Corporation■prudently■managed■its■resources■ ■■ In■measured■major■English-speaking■markets,■21■of■ in■2009-2010■and■will■continue■to■do■so■in■order■to■ 22■CBC■Radio■One■local■morning■shows■were■ranked■ ensure■financial■sustainability■within■this■environment■ first,■second■or■third■(Fall■2009■survey). of■uncertain■revenues■and■increasing■production■costs. ■■ CBC■Television’s■2+■regular■season,■prime-time■ THE RESPONSE audience■share■of■9.3■per■cent■was■up■from■last■ ■■ CBC■|■Radio-Canada■developed■a■Recovery■Plan,■ year’s■8.6■per■cent,■and■its■share■of■25-54■year-olds■ cancelled■or■scaled■back■programming■across■our■ rose■from■7.0■per■cent■to■8.0■per■cent.■The■network’s■ networks,■and■eliminated■approximately■800■full-time■ predominantly■Canadian■prime-time■schedule■ positions,■triggering■$36■million■in■downsizing■costs.■ continued■to■beat■a■key■competitor’s■primarily■ The■Corporation■also■sold■$153■million■of■long-term■ American■prime-time■schedule. accounts■receivable. ■■ CBC.ca■–■Canada’s■most■popular■English-language■ ■■ Together,■these■actions■allowed■CBC■|■Radio-Canada■to■ news■and■media■site■averaged■4.8■million■unique■ achieve■cost■reductions■related■to■operations. -

Detailed Information Including Programming from 2 Am

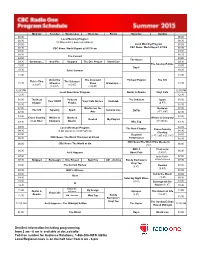

Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday 06:00 06:00 Local Morning Program 06:30 06:30 (5:30am start in selected markets) 07:00 Local Morning Program 07:00 07:30 CBC News: World Report at 5/6/7/8 am CBC News: World Report 6/7/8/9 07:30 08:00 08:00 08:30 08:30 The Current 09:00 09:00 The House 09:30 Grownups… New Fire Stripped The Doc Project Short Cuts 09:30 The Sunday Edition 10:00 10:00 Day 6 10:30 Q the Summer 10:30 11:00 11:00 Under the The Irrelevant Podcast Playlist The 180 This is That The Debaters 11:30 Influence Show Grownups… 11:30 (3:30 NT) (3:30 NT) (3:30 NT) (3:30 NT) 12:00 PM 12:00 PM Local Noon Hour Program Quirks & Quarks Vinyl Café 12:30 12:30 01:00 The Next Podcast The Debaters Spark 01:00 Your DNTO Vinyl Café Stories Radiolab Chapter Playlist (4 PT) 01:30 01:30 02:00 Wachtel on the Radiolab 02:00 The 180 Tapestry Spark Canada Live DNTO 02:30 Arts (3 PT, 4 MT) 02:30 03:00 03:00 Cross Country Writers & Quirks & Writers & Company Rewind My Playlist 03:30 in an Hour Company Quarks Wire Tap (5PT/MT/CT) 03:30 04:00 Local Afternoon Program 04:00 The Next Chapter Cross Country 04:30 (3 pm start in selected markets) 04:30 Checkup 05:00 05:00 Regional (1 PT, 2 MT, 3 CT, 5 AT) CBC News: The World This Hour at 4/5 pm 05:30 Performance 05:30 CBC News:The World This Weekend 06:00 CBC News: The World at Six 06:00 (7 AT) BBC 4 C'est la vie 06:30 06:30 As It Happens Short Cuts (7:30 AT) 07:00 In the Field + 07:00 07:30 Stripped By Design Doc Project New Fire AIH - Archive Randy Bachman's Living Out Loud 07:30 Vinyl Tap -

Canada's Top Climate Change Risks

Canada’s Top Climate Change Risks The Expert Panel on Climate Change Risks and Adaptation Potential ASSESSING EVIDENCE INFORMING DECISIONS CANADA’S TOP CLIMATE CHANGE RISKS The Expert Panel on Climate Change Risks and Adaptation Potential ii Canada’s Top Climate Change Risks THE COUNCIL OF CANADIAN ACADEMIES 180 Elgin Street, Suite 1401, Ottawa, ON, Canada K2P 2K3 Notice: The project that is the subject of this report was undertaken with the approval of the Board of Directors of the Council of Canadian Academies (CCA). Board members are drawn from the Royal Society of Canada (RSC), the Canadian Academy of Engineering (CAE), and the Canadian Academy of Health Sciences (CAHS), as well as from the general public. The members of the expert panel responsible for the report were selected by the CCA for their special competencies and with regard for appropriate balance. This report was prepared for the Government of Canada in response to a request from the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat. Any opinions, findings, or conclusions expressed in this publication are those of the authors, the Expert Panel on Climate Change Risks and Adaptation Potential and do not necessarily represent the views of their organizations of affiliation or employment, or the sponsoring organization, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat. Library and Archives Canada ISBN: 978-1-926522-67-8 (electronic book) 978-1-926522-66-1 (paperback) This report should be cited as: Council of Canadian Academies, 2019. Canada’s Top Climate Change Risks, Ottawa (ON): The Expert Panel on Climate Change Risks and Adaptation Potential, Council of Canadian Academies. -

Radio One F 09 NB

New Brunswick MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 5:00 CBC Radio Overnight 5:00 CBC Radio Overnight 5:30 Daybreak 5:30 6:00 6:00 6:30 Information Morning Weekend Mornings Weekend Mornings 6:30 7:00 CBC News: CBC News: 7:00 7:30 CBC News: World Report at 6/7/8 am World Report World Report 7:30 8:00 at 7/8/9 am at 8/9 am 8:00 8:30 Maritime Magazine 8:30 9:00 The Current 9:00 The House 9:30 9:30 10:00 White Coat, Black Art 10:00 The Sunday Edition 10:30 Q 10:30 11:00 11:00 GO! White Coat, C'est la vie The Debaters Afghanada Q 11:30 Black Art 11:30 12:00 PM 12:00 PM Maritime Noon Quirks & Quarks Vinyl Café 12:30 12:30 1:00 The Next The Story from Living Out The Debaters 1:00 In the Field Dispatches Spark 1:30 Chapter Here Loud Wire Tap 1:30 2:00 Ideas in the Writers & 2:00 Your DNTO Rewind Canada Live Tapestry 2:30 Afternoon Company Definitely Not The 2:30 3:00 Opera 3:00 Close To Home Writers & Company 3:30 3:30 4:00 SHIFT 4:00 The Next Chapter All The Best 4:30 4:30 5:00 CBC News: The World This Hour at 4/5 pm Cross Country 5:00 Atlantic Airwaves 5:30 Checkup 5:30 6:00 CBC News: The World at Six CBC News:The World This Weekend 6:00 6:30 Laugh Out Loud C'est la vie 6:30 7:00 As It Happens 7:00 Dispatches 7:30 Randy Bachman's 7:30 8:00 Vinyl Tap 8:00 The Current Review In the Field 8:30 8:30 9:00 9:00 Ideas Inside the Music 9:30 9:30 Saturday Night Blues 10:00 10:00 Q 10:30 10:30 Tonic 11:00 Quirks & The Story from Afghanada 11:00 Vinyl Café A Propos 11:30 Quarks Here Wire Tap Randy 11:30 Bachman's 12:00 AM 12:00 AM As It Happens - The Midnight Edition Vinyl Tap The Strand Rewind 12:30 12:30 1:00 1:00 CBC Radio Overnight 1:30 1:30 local/regional program Detailed program information is available at cbc.ca/radio Toll-free number for Audience Relations: 1-866-306-INFO (4636) Local/Regional news on the half hour from 6 am - 6 pm.