Policy Perspectives on First Nations Issues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Core 1..48 Committee (PRISM::Advent3b2 10.50)

House of Commons CANADA Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage CHPC Ï NUMBER 033 Ï 2nd SESSION Ï 39th PARLIAMENT EVIDENCE Tuesday, June 3, 2008 Chair Mr. Gary Schellenberger Also available on the Parliament of Canada Web Site at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 1 Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage Tuesday, June 3, 2008 Ï (1535) year, the concert was aired for the first time on Radio 2's Canada [English] Live as a result of the opening up of broadcast opportunities for more than classical music. We welcome that change. The Chair (Mr. Gary Schellenberger (Perth—Wellington, CPC)): Good afternoon, everyone. Welcome to meeting number 33 of the Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage. ln 1988, CBC Radio producers of the now defunct The Entertainers approached me, in my role as artistic director of Pursuant to Standing Order 108(2), we are undertaking a study on Toronto's Harbourfront Centre summer concert season, regarding an the dismantling of the CBC Radio Orchestra, on CBC/Radio- opportunity to record elements of the then-just-Iaunched WOMAD Canada's commitment to classical music, and the changes to CBC —Worlds of Music Arts and Dance—festival. It was a revelation. Radio 2. The partnership involved a model whereby a $25,000 blanket fee I welcome all our witnesses here today. Our witnesses are Derek would give CBC the right to record performances. Thirty-three Andrews, president of the Toronto Blues Society; Dominic Lloyd, concerts were recorded that year, and thus began a partnership that artistic director of the West End Cultural Centre; Katherine Carleton, involved many further concert recordings over the years. -

Fuelling the Surge: the University of Regina's Role in Saskatchewan's Growth

Report Fuelling the Surge: The University of Regina’s Role in Saskatchewan’s Growth The Conference Board of Canada July 2012 Fuelling the Surge: The University of Regina’s Role in Saskatchewan’s Growth 2 Fuelling the Surge: The University of Regina’s Role in Saskatchewan’s Growth by The Conference Board of Canada About The Conference Board of Canada We are: The foremost independent, not-for-profit, applied research organization in Canada. Objective and non-partisan. We do not lobby for specific interests. Funded exclusively through the fees we charge for services to the private and public sectors. Experts in running conferences but also at conducting, publishing, and disseminating research; helping people network; developing individual leadership skills; and building organizational capacity. Specialists in economic trends, as well as organizational performance and public policy issues. Not a government department or agency, although we are often hired to provide services for all levels of government. Independent from, but affiliated with, The Conference Board, Inc. of New York, which serves nearly 2,000 companies in 60 nations and has offices in Brussels and Hong Kong. Acknowledgements This report was prepared under the direction of Diana MacKay, Director, Education, Health and Immigration. Michael Bloom, Vice-President, Organizational Effectiveness and Learning provided strategic advice and oversight. The primary author was Jessica Brichta. Michael Bloom, Caitlin Charman, Ryan Godfrey, Michael Grant, and Diana MacKay made Conference Board staff contributions to the report. Marie-Christine Bernard, Michael Burt, Donna Burnett-Vachon, Len Coad, Mario Lefebvre, Dan Munro, Matthew Stewart, Hitomi Suzuta, and Douglas Watt conducted internal Conference Board reviews. -

Born to Lead Meetmeet FSINFSIN Chiefchief Perryperry Bellegardebellegarde the Sky’S the Limit Climateclimate Changechange Researchresearch

UNIVERSITY OF REGINA ALUMNI MAGAZINE SPRINGSPRING 2003,2003, VOLUMEVOLUME 15,15, NUMBERNUMBER 11 Born to lead MeetMeet FSINFSIN ChiefChief PerryPerry BellegardeBellegarde The sky’s the limit ClimateClimate changechange researchresearch Editor University of Regina Greg Campbell ’85, ’95 Alumni Magazine Editorial Advisors Spring 2003 Barbara Pollock ’75, ’77 Volume 15, Number 1 Therese Stecyk ’84 Shane Reoch ’97 Carlo Binda ’95, ’93 Lisa King ’95 Alumni Association Board 2002-03 Shane Reoch ’97 President Greg Swanson ’76 Past-President Matt Hanson ’94, ’97 First V-P FEATURES Lisa King ’95 Second V-P Brian Munro ’96, ’96 6 The sky's the limit V-P Finance The University is quickly establishing an international reputation for excellence in climate change research. Here are Carlo Binda ’95, ’93 Debra Clark ’96 some of the reasons why. Donna Easto ’90 Mary Klassen ’84 Loanne Myrah ’94, ’82 10 Born to lead Dean Reeve ’84 Meet Chief Perry Bellegarde (BAdmin’84), one of the young Contributors First Nations leaders committed to protecting treaty rights and John Chaput ’98 6 Scott Irving ’94 guiding his people to a brighter future. Michelle Van Ginneken ’96 Deborah Sproat 27 Last Word Introducing some of our newest faculty members with answers The Third Degree is published twice a year by University Relations at the University of Regina. to the questions that you want to know. The magazine is mailed to alumni and friends of the University. Ideas and opinions published in The Third Degree do not necessarily reflect those of the editor, the Alumni Association or the University of Regina. -

A Canada Fit for Children

A CANADA FIT FOR CHILDREN Canada’s follow-up to the United Nations General Assembly Special Session on Children, dated April 2004. 1 Aussi disponible en français sous le titre Un Canada digne des enfants April 2004 © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2004 Paper Catalogue No. SD13-4/2004E ISBN 0-662-36985-8 PDF Catalogue No. SD13-4/2004E-PDF ISBN 0-662-36991-2 HTML Catalogue No. SD13-4/2004E-HTML ISBN 0-662-36992-0 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page A message from the Prime Minister. 5 A message from the Minister of Health and the Minister of Social Development . 7 A message from Senator Landon Pearson . 9 A message from the young people of CEERT . 11 A Canada Fit for Children I. Preface . 13 II. Declaration . 15 III. Toward a Common Canadian Vision for Children . 19 IV. Plan of Action. 37 A. Creating a Canada and a World Fit for Children. 37 B. Goals, Strategies and Actions for Canada . 41 1. Supporting Families and Strengthening Communities . 41 2. Promoting Healthy Lives. 50 3. Protecting from Harm . 64 4. Promoting Education and Learning. 78 C. Building Momentum . 87 A Call to Action . 87 Partnerships and Participation . 87 Keeping on Track . 90 V. Government of Canada Investments in and Commitments to Children. 93 A. For Canada's Children. 93 B. For the World's Children. 113 3 4 A message from the Prime Minister The children of today constitute the largest generation of young people the world has ever known. And the world will be profoundly affected by their actions and decisions – not only in the years to come, but even right now. -

Survivors Share Common Experiences

JUNE 2018 VOLUME 21 - NUMBER 6 FREE Survivors share common experiences Holocaust survivor Nate Leipciger and residen - tial school survivor Eugene Arcand gathered for a dialogue to discuss the commonalities of their experiences. (Photo by David Fisher) CELEBRATING SCHOOL It has been 20 years since George Gordon Education Centre replaced its residential school with a new facility. - Page 7 AT THE HELM OF MVA Andrea Lafond comes to her new role as CEO of the Meewasin Valley Authority with a perfect background for the job. - Pag e 9 TIPI PAINTING Some very special artists have landed the perfect summer jobs and they couldn’t be more pleased. - Page 11 NURSING EXCELLENCE Bodeine Dusion recently won a prestigous award and she’s inspired to do even more for her community. - Page 17 INSPIRING STUDENTS These have been difficult times for young people in the Battle - ford but Tarrant Cross Child is By Jeanelle Mandes students to provide the audience with a deeper under - helping them cope. - Page 23 Of Eagle Feather News standing of the challenges they faced. Two survivors from different traumatic times in “I spoke with Eugene and we had common expe - history sat down to have a dialogue called the Coura - riences, common trauma and certain common loss,” National Aboriginal Day Edition geous Conversation. Leipciger said after the session in early June. Coming In July - Graduation Issue Residential school survivor Eugene Arcand and “We (didn’t) compare our suffering but we talked Holocaust Survivor Nate Leipciger shared their stories about the common elements of our past.” CPMA #40027204 with one another in front of over a thousand Saskatoon Continued on Page 2 Eagle Feather News JUNE 2018 2 Arcand, Leipciger endured trauma in residential schools, concentration camps Continued from Page One Leipciger, originally from Poland, survived the Holocaust in German-occupied Poland. -

BC's Music Sector

BC’s Music Sector FROM ADVERSITY TO OPPORTUNITY www.MusicCanada.com /MusicCanada @Music_Canada BC’S MUSIC SECTOR: FROM ADVERSITY TO OPPORTUNITY A roadmap to reclaim BC’s proud music heritage and ignite its potential as a cultural and economic driver. FORWARD | MICHAEL BUBLÉ It’s never been easy for artists to get a start in We all have a role to play. Record labels and music. But it’s probably never been tougher other music businesses need to do a better than it is right now. job. Consumers have to rethink how they consume. Governments at all levels have to My story began like so many other kids recalibrate their involvement with music. And with a dream. I was inspired by some of successful artists have to speak up. the greatest singers – Ella Fitzgerald, Tony Bennett and Frank Sinatra – listening to my We all have to pull together and take action. grandfather’s record collection while growing up in Burnaby. I progressed from talent I am proud of the fact that BC gave me a competitions, to regular shows at local music start in a career that has given me more venues, to a wedding gig that would put me than I could have ever imagined. After in the right room with the right people – the touring around the world, I am always right BC people. grateful to come home to BC where I am raising my family. I want young artists to When I look back, I realize how lucky I was. have the same opportunities I had without There was a thriving music ecosystem in BC having to move elsewhere. -

Lifestyle at the Root of Diabetes Epidemic

FEBRUARY 2011 VOLUME 14 - NUMBER 2 FREE Pink stick scores for cancer By John Lagimodiere known as ‘sniper’because of his prowess. Of Eagle Feather News The only thing more important to him Dana Gamble has scored $500 for ana Gamble lives and breathes than hockey is his family. That is why it cancer research. (Photo by John Lagimodiere) hockey. First on the ice and last was so difficult for his mom Rae to tell off the ice every practice, this him that his Aunty Claudette was defenceman with the Peewee Aces is diagnosed with breast cancer. D “I had to tell him and his sister because they heard me crying on the phone,” explained the proud mom during the Aces Peewee Tournament during Hockey Day in Saskatoon. “And the first thing he said was that he wanted a pink hockey stick. I gave him heck for thinking of hockey at a time like this, but then he told me, ‘No mom, I want a breast cancer stick. And I want pink tape too.’ THE DOCTOR LISTENS And that is how it started.” Doctorsshouldspendmoretime Dana showed up at his listening to their patients next game with a pink stick suggestsDr.VeronicaMcKinney. and tape. Worried that his -Page10 teammates would make fun of him, Dana just went out and did what he loves to do DIABETESEPIDEMIC and proceeded to score four PaulHackettsaystheAboriginal goals. community’s lifestyle changes He told his teammates overtheyearshaveledtohealth about his aunty and breast problems. - Page 13 cancer and the response was not what he expected. OPPORTUNITY KNOCKS “They didn’t say A job fair for Aboriginal youth anything .. -

Security Coordinator

STEVE SUMMERVILLE Curriculum Vitae April 2021 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents ...................................................................... 2 Steven Summerville – Contact Information .............................. 3 Professional Background ......................................................... 3 Education ................................................................................ 10 Continuing Education ............................................................. 11 Associations ........................................................................... 16 Awards .................................................................................... 16 Crowd Control Project Management ....................................... 18 Special Events Management................................................... 19 Project Participation ............................................................... 25 Private Consulting .................................................................. 37 Media Presentations ............................................................... 68 Expert Witness Recognition ................................................... 85 April 2021 2 Steven Summerville – Contact Information STAY SAFE Instructional Programs. (SSIP) 3 Holmes Crescent Ajax, Ontario. L1T 3R6 Cell: (416)-318-8299 Email: [email protected] [email protected] Website: https://staysafeip.com/ Professional Background CANADIAN NATIONAL EXHIBITION ASSOCIATION (CNE). – Toronto, Ontario. May 2016 to present Security Coordinator. -

Of Analogue: Access to Cbc/Radio-Canada Television Programming in an Era of Digital Delivery

THE END(S) OF ANALOGUE: ACCESS TO CBC/RADIO-CANADA TELEVISION PROGRAMMING IN AN ERA OF DIGITAL DELIVERY by Steven James May Master of Arts, Ryerson University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2008 Bachelor of Applied Arts (Honours), Ryerson University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 1999 Bachelor of Administrative Studies (Honours), Trent University, Peterborough, Ontario, Canada, 1997 A dissertation presented to Ryerson University and York University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Program of Communication and Culture Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2017 © Steven James May, 2017 AUTHOR'S DECLARATION FOR ELECTRONIC SUBMISSION OF A DISSERTATION I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this dissertation. This is a true copy of the dissertation, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this dissertation to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this dissertation by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my dissertation may be made electronically available to the public. ii ABSTRACT The End(s) of Analogue: Access to CBC/Radio-Canada Television Programming in an Era of Digital Delivery Steven James May Doctor of Philosophy in the Program of Communication and Culture Ryerson University and York University, 2017 This dissertation -

Uvic Thesis Template

Running head: YOU’VE GOT TO PADDLE YOUR OWN CANOE You’ve Got to Paddle Your Own Canoe: The effects of federal legislation on participation in, and exercising of, traditional governance while living off-reserve by Tsaskiy (Ron George) Bachelor of Social Work, University of Victoria, 2006 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF EDUCATION in the Department of Educational Psychology and Leadership Studies © Tsaskiy (Ron George), 2017 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. YOU’VE GOT TO PADDLE YOUR OWN CANOE 2 Supervisory Committee You’ve Got to Paddle Your Own Canoe: The effects of federal legislation on participation in, and exercising of, traditional governance while living off-reserve by Tsaskiy (Ron George) Bachelor of Social Work, University of Victoria, 2006 Supervisory Committee Dr. Darlene Clover (Department of Educational Psychology and Leadership Studies) Supervisor Dr. Catherine McGregor (Department of Educational Psychology and Leadership Studies) Committee Member YOU’VE GOT TO PADDLE YOUR OWN CANOE 3 Abstract Supervisory Committee Dr. Darlene Clover (Department of Educational Psychology and Leadership Studies) Supervisor Dr. Catherine McGregor (Department of Educational Psychology and Leadership Studies) Committee Member This project describes the challenges and impediments members of two clans experienced while growing up and living off-reserve. Members of the Gitimt’en clan and their father clan, the Likhts’amisyu, descendants of Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Chiefs Gisdayway (Thomas George), and Tsaybaysa (Mary George) respectively, and which includes the writer, related personal experiences of living off-reserve amidst the dominant colonial culture. -

Towards a Treaty-Based Practice of Relationality by Gina Starblanket

Beyond Rights and Wrongs: Towards a Treaty-Based Practice of Relationality by Gina Starblanket M.A., University of Victoria, 2012 B.A. Hons., University of Regina, 2008 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Indigenous Governance Program ã Gina Starblanket, 2017 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Beyond Rights and Wrongs: Towards a Treaty-Based Practice of Relationality by Gina Starblanket M.A., University of Victoria, 2012 B.A. Hons., University of Regina, 2008 Supervisory Committee Dr. Heidi Kiiwetinepinesiik Stark, Department of Political Science Co-Supervisor Dr. Taiaiake Alfred, Indigenous Governance Program Co-Supervisor Dr. Jeff Corntassel, Indigenous Governance Program Departmental Member iii Abstract Supervisory Committee Dr. Heidi Kiiwetinepinesiik Stark, Department of Political Science Co-Supervisor Dr. Taiaiake Alfred, Indigenous Governance Program Co-Supervisor Dr. Jeff Corntassel, Indigenous Governance Program Departmental Member This research explores the implications of the distinction between transactional and relational understandings of the Numbered Treaties, negotiated by Indigenous peoples and the Dominion of Canada from 1871-1921. It deconstructs representations of the Numbered Treaties as “land transactions” and challenges the associated forms of oppression that emerge from this interpretation. Drawing on oral histories of the Numbered Treaties, it argues instead that they established a framework for relationship that expressly affirmed the continuity of Indigenous legal and political orders. Further, this dissertation positions treaties as a longstanding Indigenous political institution, arguing for the resurgence of a treaty-based ethic of relationality that has multiple applications in the contemporary context. -

Rev-Radio One F 09

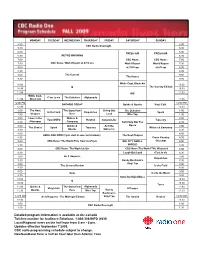

MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 5:00 5:00 CBC Radio Overnight 5:30 5:30 6:00 6:00 FRESH AIR FRESH AIR 6:30 METRO MORNING 6:30 7:00 CBC News: CBC News: 7:00 7:30 CBC News: World Report at 6/7/8 am World Report World Report 7:30 8:00 at 7/8/9 am at 8/9 am 8:00 8:30 8:30 9:00 The Current 9:00 The House 9:30 9:30 10:00 White Coat, Black Art 10:00 Q The Sunday Edition 10:30 10:30 11:00 GO! 11:00 White Coat, C'est la vie The Debaters Afghanada 11:30 Black Art 11:30 12:00 PM 12:00 PM ONTARIO TODAY Quirks & Quarks Vinyl Café 12:30 12:30 1:00 The Next The Story from Living Out The Debaters 1:00 In the Field Dispatches Spark 1:30 Chapter Here Loud Wire Tap 1:30 2:00 Ideas in the Writers & 2:00 Your DNTO Rewind Canada Live Tapestry 2:30 Afternoon Company Definitely Not The 2:30 3:00 Quirks & And the Opera 3:00 The Choice Spark Tapestry Writers & Company 3:30 Quarks Winner Is 3:30 4:00 4:00 HERE AND NOW (3 pm start in selected markets) The Next Chapter 4:30 Cross Country 4:30 5:00 CBC News: The World This Hour at 4/5 pm BIG CITY SMALL Checkup 5:00 5:30 WORLD 5:30 6:00 CBC News: The World at Six CBC News:The World This Weekend 6:00 6:30 Laugh Out Loud C'est la vie 6:30 7:00 As It Happens 7:00 Dispatches 7:30 Randy Bachman's 7:30 8:00 Vinyl Tap 8:00 The Current Review In the Field 8:30 8:30 9:00 9:00 Ideas Inside the Music 9:30 9:30 Saturday Night Blues 10:00 10:00 Q 10:30 10:30 Tonic 11:00 Quirks & The Story from Afghanada 11:00 Vinyl Café A Propos 11:30 Quarks Here Wire Tap Randy 11:30 Bachman's 12:00 AM As It Happens - The Midnight Edition Vinyl Tap The Strand Rewind 12:00 AM 12:30 12:30 1:00 1:00 CBC Radio Overnight 1:30 1:30 Detailed program information is available at cbc.ca/radio Toll-free number for Audience Relations: 1-866-306-INFO (4636) Local/Regional news on the half hour from 6 am - 6 pm.