Dark Arts the World Beyond Visible Light Over the Transom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Apocalypse Archive: American Literature and the Nuclear

THE APOCALYPSE ARCHIVE: AMERICAN LITERATURE AND THE NUCLEAR BOMB by Bradley J. Fest B. A. in English and Creative Writing, University of Arizona, Tucson, 2004 M. F. A. in Creative Writing, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, 2007 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2013 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Bradley J. Fest It was defended on 17 April 2013 and approved by Jonathan Arac, PhD, Andrew W. Mellon Professor of English Adam Lowenstein, PhD, Associate Professor of English and Film Studies Philip E. Smith, PhD, Associate Professor of English Terry Smith, PhD, Andrew W. Mellon Professor of Contemporary Art History and Theory Dissertation Director: Jonathan Arac, PhD, Andrew W. Mellon Professor of English ii Copyright © Bradley J. Fest 2013 iii THE APOCALYPSE ARCHIVE: AMERICAN LITERATURE AND THE NUCLEAR BOMB Bradley J. Fest, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2013 This dissertation looks at global nuclear war as a trope that can be traced throughout twentieth century American literature. I argue that despite the non-event of nuclear exchange during the Cold War, the nuclear referent continues to shape American literary expression. Since the early 1990s the nuclear referent has dispersed into a multiplicity of disaster scenarios, producing a “second nuclear age.” If the atomic bomb once introduced the hypothesis “of a total and remainderless destruction of the archive,” today literature’s staged anticipation of catastrophe has become inseparable from the realities of global risk. -

Comedians, Characters, Cable Guys & Copyright Convolutions

Legal Lessons in On-Stage Character Development: Comedians, Characters, Cable Guys & Copyright Convolutions Clay Calvert⊗ ABSTRACT This article addresses the trials and tribulations faced by stand-up comedians who seek copyright protection for on-stage characters they create, often during solo performances. The article initially explores the current, confused state of the law surrounding the copyrightability of fictional characters. The doctrinal muddle is magnified for comedians because the case law that addresses the fictional character facet of copyright jurisprudence overwhelmingly involves characters developed within the broader framework of plots and storylines found in traditional media artifacts such as books, comic strips, cartoons and movies. The article then deploys the 2014 federal court ruling in Azaria v. Bierko as a timely analytical springboard for addressing comedic-character copyright issues. Finally, the article offers multiple tips and suggestions for comedians and actors seeking copyright protection in their on- stage characters. I. INTRODUCTION The Whacky World of Jonathan Winters aired on television from 1972 through 1974.1 The humor of its star, Jonathan Winters,2 came primarily “from his construction of outrageously fantastic situations and characters.”3 Those characters included the Oldest Airline Stewardess4 and, perhaps most notably, ⊗ Professor & Brechner Eminent Scholar in Mass Communication and Director of the Marion B. Brechner First Amendment Project at the University of Florida, Gainesville, Fla. B.A., 1987, Communication, Stanford University; J.D. (Order of the Coif), 1991, McGeorge School of Law, University of the Pacific; Ph.D., 1996, Communication, Stanford University. Member, State Bar of California. The author thanks students Kevin Bruckenstein, Karilla Dyer, Alexa Jacobson, Tershone Phillips and Brock Seng of the University of Florida for their research, suggestions and editing assistance that contributed to this article. -

Comic Book Collection

2008 preview: fre comic book day 1 3x3 Eyes:Curse of the Gesu 1 76 1 76 4 76 2 76 3 Action Comics 694/40 Action Comics 687 Action Comics 4 Action Comics 7 Advent Rising: Rock the Planet 1 Aftertime: Warrior Nun Dei 1 Agents of Atlas 3 All-New X-Men 2 All-Star Superman 1 amaze ink peepshow 1 Ame-Comi Girls 4 Ame-Comi Girls 2 Ame-Comi Girls 3 Ame-Comi Girls 6 Ame-Comi Girls 8 Ame-Comi Girls 4 Amethyst: Princess of Gemworld 9 Angel and the Ape 1 Angel and the Ape 2 Ant 9 Arak, Son of Thunder 27 Arak, Son of Thunder 33 Arak, Son of Thunder 26 Arana 4 Arana: The Heart of the Spider 1 Arana: The Heart of the Spider 5 Archer & Armstrong 20 Archer & Armstrong 15 Aria 1 Aria 3 Aria 2 Arrow Anthology 1 Arrowsmith 4 Arrowsmith 3 Ascension 11 Ashen Victor 3 Astonish Comics (FCBD) Asylum 6 Asylum 5 Asylum 3 Asylum 11 Asylum 1 Athena Inc. The Beginning 1 Atlas 1 Atomic Toybox 1 Atomika 1 Atomika 3 Atomika 4 Atomika 2 Avengers Academy: Fear Itself 18 Avengers: Unplugged 6 Avengers: Unplugged 4 Azrael 4 Azrael 2 Azrael 2 Badrock and Company 3 Badrock and Company 4 Badrock and Company 5 Bastard Samurai 1 Batman: Shadow of the Bat 27 Batman: Shadow of the Bat 28 Batman:Shadow of the Bat 30 Big Bruisers 1 Bionicle 22 Bionicle 20 Black Terror 2 Blade of the Immortal 3 Blade of the Immortal unknown Bleeding Cool (FCBD) Bloodfire 9 bloodfire 9 Bloodshot 2 Bloodshot 4 Bloodshot 31 bloodshot 9 bloodshot 4 bloodshot 6 bloodshot 15 Brath 13 Brath 12 Brath 14 Brigade 13 Captain Marvel: Time Flies 4 Caravan Kidd 2 Caravan Kidd 1 Cat Claw 1 catfight 1 Children of -

Blue, Gold, & Black 2006

COVER STORY Donald M. Henderson First Black Pitt Provost, 1989 Page 24 Chancellor Mark A. NordenbergNordenberg ReportReportss on the Pitt African African American Experience Experience COVER STORY Donald M. Henderson First Black Pitt Provost, 1989 Page 24 2006 2004 2002 On the cover: Rose Afriyie graduated from the University of Pittsburgh in 2006 with a degree in English writing and political science. An E GOL Alpha Kappa Alpha sister, she was a Black BLU D Action Society member, BlackLine committee chair, Pitt News opinions editor, Pitt Chronicle contributor, and vice president of the African Amer - & BLACK ican Coalition for Advancement, Achievement, Suc - cess and Excellence. 2006 Along with Chancellor Mark A. Nordenberg, Millersville University President Francine G. Mc - Nairy (CAS ’68, SOC WK ’70, FAS ’78), and Pitt Professor Emeritus and former Provost Donald M. Henderson (FAS ’67), Afriyie presented a tribute to Jack L. Daniel (see page 48) . UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH Contents C H A P T E R 1 : A F R I C A N AM E R I C A N AL U M N I CO U N C I L . .4 C H A P T E R 2 : C O V E R ST O R Y : D O N A L D M. HE N D E R S O N . .2 4 C H A P T E R 3 : A W A R D S , HO N O R S , AN D SC H O L A R S H I P S . .3 0 C H A P T E R 4 : P R O F I L E S . -

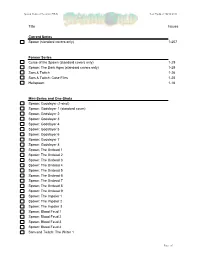

Spawn Comics Checklist (USA)

Spawn Comics Checklist (USA) Last Updated: 06/18/2011 Title Issues Current Series Spawn (standard covers only) 1-207 Former Series Curse of the Spawn (standard covers only) 1-29 Spawn: The Dark Ages (standard covers only) 1-28 Sam & Twitch 1-26 Sam & Twitch: Case Files 1-25 Hellspawn 1-16 Mini-Series and One-Shots Spawn: Godslayer (1-shot) Spawn: Godslayer 1 (standard cover) Spawn: Godslayer 2 Spawn: Godslayer 3 Spawn: Godslayer 4 Spawn: Godslayer 5 Spawn: Godslayer 6 Spawn: Godslayer 7 Spawn: Godslayer 8 Spawn: The Undead 1 Spawn: The Undead 2 Spawn: The Undead 3 Spawn: The Undead 4 Spawn: The Undead 5 Spawn: The Undead 6 Spawn: The Undead 7 Spawn: The Undead 8 Spawn: The Undead 9 Spawn: The Impaler 1 Spawn: The Impaler 2 Spawn: The Impaler 3 Spawn: Blood Feud 1 Spawn: Blood Feud 2 Spawn: Blood Feud 3 Spawn: Blood Feud 4 Sam and Twitch: The Writer 1 Page of Spawn Comics Checklist (USA) Last Updated: 06/18/2011 Sam and Twitch: The Writer 2 Sam and Twitch: The Writer 3 Sam and Twitch: The Writer 4 Angela 1 Angela 2 Angela 3 Cy-Gor 1 Cy-Gor 2 Cy-Gor 3 Cy-Gor 4 Cy-Gor 5 Cy-Gor 6 Violator 1 Violator 2 Violator 3 Spawn: Blood & Shadows (Annual 1) Spawn Bible (1st Print) Spawn Bible (2nd Print) Spawn Bible (3rd Print) Spawn: Book of Souls Spawn: Blood & Salvation Spawn: Simony Spawn: Architects of Fear The Adventures of Spawn Director’s Cut The Adventures of Spawn 2 Celestine 1 (green) Celestine 1 (purple) Celestine 2 Spawn Manga (Shadows of Spawn) vol1 (1st Print) Spawn Manga (Shadows of Spawn) vol1 (2nd Print) Spawn Manga (Shadows of Spawn) -

Azbill Sawmill Co. I-40 at Exit 101 Southside Cedar Grove, TN 731-968-7266 731-614-2518, Michael Azbill [email protected] $6,0

Azbill Sawmill Co. I-40 at Exit 101 Southside Cedar Grove, TN 731-968-7266 731-614-2518, Michael Azbill [email protected] $6,000 for 17,000 comics with complete list below in about 45 long comic boxes. If only specific issue wanted email me your inquiry at [email protected] . Comics are bagged only with no boards. Have packed each box to protect the comics standing in an upright position I've done ABSOLUTELY all the work for you. Not only are they alphabetzied from A to Z start to finish, but have a COMPLETE accurate electric list. Dates range from 1980's thur 2005. Cover price up to $7.95 on front of comic. Dates range from mid to late 80's thru 2005 with small percentage before 1990. Marvel, DC, Image, Cross Gen, Dark Horse, etc. Box AB Image-Aaron Strain#2(2) DC-A. Bizarro 1,3,4(of 4) Marvel-Abominations 2(2) Antartic Press-Absolute Zero 1,3,5 Dark Horse-Abyss 2(of2) Innovation- Ack the Barbarion 1(3) DC-Action Comis 0(2),599(2),601(2),618,620,629,631,632,639,640,654(2),658,668,669,671,672,673(2),681,684,683,686,687(2/3/1 )688(2),689(4),690(2),691,692,693,695,696(5),697(6),701(3),702,703(3),706,707,708(2),709(2),712,713,715,716( 3),717(2),718(4),720,688,721(2),722(2),723(4),724(3),726,727,728(3),732,733,735,736,737(2),740,746,749,754, 758(2),814(6), Annual 3(4),4(1) Slave Labor-Action Girl Comics 3(2) DC-Advanced Dungeons & Dragons 32(2) Oni Press-Adventrues Barry Ween:Boy Genius 2,3(of6) DC-Adventrure Comics 247(3) DC-Adventrues in the Operation:Bollock Brigade Rifle 1,2(2),3(2) Marvel-Adventures of Cyclops & Phoenix 1(2),2 Marvel-Adventures -

The Political Image of William Pitt, First Earl of Chatham, in the American Colonial Press, 1756-1778

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1974 The political image of William Pitt, first earl of Chatham, in the American colonial press, 1756-1778 Carol Lynn Homelsky Knight College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Knight, Carol Lynn Homelsky, "The political image of William Pitt, first earl of Chatham, in the American colonial press, 1756-1778" (1974). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623667. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-zm1q-vg14 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. -

Postmodern Themes in American Comics Circa 2001-2018

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Theses Department of History 5-8-2020 The Aluminum Age: Postmodern Themes in American Comics Circa 2001-2018 Amy Collerton Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses Recommended Citation Collerton, Amy, "The Aluminum Age: Postmodern Themes in American Comics Circa 2001-2018." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2020. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses/126 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ALUMINUM AGE: POSTMODERN THEMES IN AMERICAN COMICS CIRCA 1985- 2018 by AMY COLLERTON Under the Direction of John McMillian, PhD ABSTRACT This thesis seeks to update the fan-made system of organization for comic book history. Because academia ignored comics for much of their history, fans of the medium were forced to design their own system of historical organization. Over time, this system of ages was adopted not only by the larger industry, but also by scholars. However, the system has not been modified to make room for comics published in the 21st century. Through the analysis of a selection modern comics, including Marvel’s Civil War and DC Comics’ Infinite Crisis, this thesis suggests a continuation of the age system, the Aluminum Age (2001-the present). Comics published during the Aluminum Age incorporate Postmodern themes and are unique to the historical context in which they were published. -

Comic Book Fandom

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2015-01-01 Comic Book Fandom: An Exploratory Study Into The orW ld Of Comic Book Fan Social Identity Through Parasocial Theory Anthony Robert Ramirez University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Ramirez, Anthony Robert, "Comic Book Fandom: An Exploratory Study Into The orldW Of Comic Book Fan Social Identity Through Parasocial Theory" (2015). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 1131. https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd/1131 This is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMIC BOOK FANDOM: AN EXPLORATORY STUDY INTO THE WORLD OF COMIC BOOK FAN SOCIAL IDENTITY THROUGH PARASOCIAL THEORY ANTHONY R. RAMIREZ Department of Communication APPROVED: _____________________________ Roberto Avant-Mier, Ph.D., Chair _____________________________ Thomas Ruggiero, Ph.D. _____________________________ Brian Yothers, Ph.D. ___________________________ Charles Ambler, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School Copyright © by Anthony Robert Ramirez 2015 COMIC BOOK FANDOM: AN EXPLORATORY STUDY INTO THE WORLD OF COMIC BOOK FAN SOCIAL IDENTITY THROUGH PARASOCIAL THEORY by ANTHONY R. RAMIREZ B.F.A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at El Paso in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of Communication THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT EL PASO May 2015 ABSTRACT Comic books and their extensive lineup of characters have invaded all types of media forms, making comics a global media phenomenon that are having a wider profile in media and popular culture. -

A Pocket Manual of North Carolina for the Use of Members of the General Assembly

A POCKET MANUAL OF NORTH CAROLINA FOR THE USE OF 1EMBERS OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY SESSION 1909. COMPILED AND ISSUED BY THE NORTH CAROLINA HISTORICAL COMMISSION 1909. f^ PREFACE. This little volume was compiled by the Historical Commission in order to furnish to the members of the General Assembly of L909, in convenient form, information about the Stale which otherwise would require much investigation in many different sources. It is also hoped that it may prove of value and service to others who desire to have in succinct form such data about North Carolina. Similar Manuals, issued in 1905 and 1!)(>7 by the Secretary of State, have proven of very general utility and interest. Requests for copies have come not only from all over North Carolina, but from most of the for them has been so -rent thai I States of the Union, and the demand editions have been and it is now extremely dif I both long exhausted, ficult to secure a copy. A comparatively small number of copie the .Manual for 1909 have been printed, because it is (lie hope of the Historical Commission later to elaborate it, incorporating a great deal more data about the State, and giving North Carolina a Manual equal to those issued by the other States of the Union. In the meantime the Historical Commission trusts that the mem hers of the General Assembly of 1909 will find this little volume of service to them in their work. r c r CALENDAR, 1909. OFFICIAL REGISTER FOR THE YEAR 1909. LEGISLATIVE DEPARTMENT. William C. -

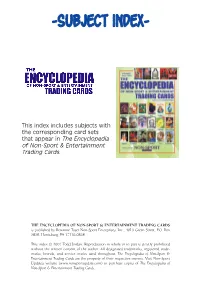

Subject Index

-Subject Index- This index includes subjects with the corresponding card sets that appear in The Encyclopedia of Non-Sport & Entertainment Trading Cards. THE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF NON-SPORT & ENTERTAINMENT TRADING CARDS is published by Roxanne Toser Non-Sport Enterprises, Inc., 4019 Green Street, P.O. Box 5858, Harrisburg, PA 17110-0858. This index © 2007 Todd Jordan. Reproduction in whole or in part is strictly prohibited without the written consent of the author. All designated trademarks, registered trade- marks, brands, and service marks used throughout The Encyclopedia of Non-Sport & Entertainment Trading Cards are the property of their respective owners. Visit Non-Sport Update’s website (www.nonsportupdate.com) to purchase copies of The Encyclopedia of Non-Sport & Entertainment Trading Cards. The Encyclopedia of Non-Sport & Entertainment Trading Cards ■ 1 Animation (see Movies: Animation, Foss; Civil War: The Art of Mort Secret Desires; Mars Attacks! Archives; and Television: Animation) Kunstler; Clive Barker; Clyde Masterpiece Collection; Masters of INDEX - Subjects Caldwell; Colossal Cards I; Colossal Fantasy Metallic; Maxfield Parrish; Anime (sets featuring Japanese ani- Cards Series 2; Comic Images Michael Kaluta; Michael Kaluta Series mation, both television and movies) Supreme; Creators Master Series; Two; Michael Whelan; Michael Akira; Akira Preview; Beyblade; Crimes Against the Eye; Crimson Whelan II Other Worlds; Midnight Cardcaptors; CPM Manga The Art of Embrace; Darrell K. Sweet; Dave Madness; Mike Ploog Fantastic Art; Satoshi -

'Comic Book' Superhero

Wayne State University Wayne State University Dissertations 1-1-2015 Turning The aP ge: Fandoms, Multimodality, And The rT ansformation Of The comic' Book' Superhero Matthew Alan Cicci Wayne State University, Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Other Communication Commons Recommended Citation Cicci, Matthew Alan, "Turning The aP ge: Fandoms, Multimodality, And The rT ansformation Of The c' omic Book' Superhero" (2015). Wayne State University Dissertations. Paper 1331. This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. TURNING THE PAGE: FANDOMS, MULTIMODALITY, AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF THE “COMIC BOOK” SUPERHERO by MATTHEW ALAN CICCI DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2015 MAJOR: ENGLISH (Film & Media Studies) Approved By: ____________________________________________ Advisor Date ____________________________________________ ____________________________________________ ____________________________________________ ____________________________________________ DEDICATION I would like to dedicate this work to my wife, Lily, and my three children, Maya, Eli, and Samuel. Without my wife’s ceaseless support, patience, and love, I would have been unable to complete this work in a timely manner. And, without the unquantifiable joy my children bring me, I am positive the more difficult parts of writing this dissertation would have been infinitely more challenging. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank all of my committee members—Dr. Jeff Pruchnic, Dr. Steven Shaviro, and Dr.