Comic Book Fandom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Click Above for a Preview, Or Download

JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR FORTY-TWO $9 95 IN THE US Guardian, Newsboy Legion TM & ©2005 DC Comics. Contents THE NEW OPENING SHOT . .2 (take a trip down Lois Lane) UNDER THE COVERS . .4 (we cover our covers’ creation) JACK F.A.Q. s . .6 (Mark Evanier spills the beans on ISSUE #42, SPRING 2005 Jack’s favorite food and more) Collector INNERVIEW . .12 Jack created a pair of custom pencil drawings of the Guardian and Newsboy Legion for the endpapers (Kirby teaches us to speak the language of the ’70s) of his personal bound volume of Star-Spangled Comics #7-15. We combined the two pieces to create this drawing for our MISSING LINKS . .19 front cover, which Kevin Nowlan inked. Delete the (where’d the Guardian go?) Newsboys’ heads (taken from the second drawing) to RETROSPECTIVE . .20 see what Jack’s original drawing looked like. (with friends like Jimmy Olsen...) Characters TM & ©2005 DC Comics. QUIPS ’N’ Q&A’S . .22 (Radioactive Man goes Bongo in the Fourth World) INCIDENTAL ICONOGRAPHY . .25 (creating the Silver Surfer & Galactus? All in a day’s work) ANALYSIS . .26 (linking Jimmy Olsen, Spirit World, and Neal Adams) VIEW FROM THE WHIZ WAGON . .31 (visit the FF movie set, where Kirby abounds; but will he get credited?) KIRBY AS A GENRE . .34 (Adam McGovern goes Italian) HEADLINERS . .36 (the ultimate look at the Newsboy Legion’s appearances) KIRBY OBSCURA . .48 (’50s and ’60s Kirby uncovered) GALLERY 1 . .50 (we tell tales of the DNA Project in pencil form) PUBLIC DOMAIN THEATRE . .60 (a new regular feature, present - ing complete Kirby stories that won’t get us sued) KIRBY AS A GENRE: EXTRA! . -

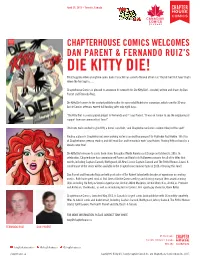

DIE KITTY DIE! What Happens When a Longtime Comic Book Character Has Come to the End of Her Run? You Kill Her! but How? That’S Where the Fun Begins…

April 25, 2015 – Toronto, Canada CHAPTERHOUSE COMICS WELCOMES DAN PARENT & FERNANDO RUIZ’S DIE KITTY DIE! What happens when a longtime comic book character has come to the end of her run? You kill her! But how? That’s where the fun begins….. Chapterhouse Comics is pleased to announce its newest title: Die Kitty Die! - created, written and drawn by Dan Parent and Fernando Ruiz. Die Kitty Die! comes to the upstart publisher after its successful Kickstarter campaign, which saw the 30-year Archie Comics veterans exceed full funding after only eight days. “Die Kitty Die! is a very special project for Fernando and I” says Parent, “It was an honour to see the outpouring of support from our community of fans!” ‘And now, we’re excited to give Kitty a home’ says Ruiz, ‘and Chapterhouse Comics seemed like just the spot!’ Finding a place in Chapterhouse’s ever-growing roster is an exciting prospect for Publisher Fadi Hakim. ’All of us at Chapterhouse grew up reading and still read Dan and Fernando’s work’ says Hakim. ‘Having Kitty on board is a dream come true!’ Die Kitty Die! releases to comic book stores throughout North America and Europe on October 26, 2016. In celebration, Chapterhouse has commissioned Parent and Ruiz to do Halloween variants for all of its titles that month, including Captain Canuck, Northguard, All-New Classic Captain Canuck and The Pitiful Human-Lizard. A small teaser of the series will be available in the Chapterhouse Summer Special 2016, releasing this June! Dan Parent and Fernando Ruiz are both graduates of The Kubert School with decades of experience in creating comics. -

Representations of Education in HBO's the Wire, Season 4

Teacher EducationJames Quarterly, Trier Spring 2010 Representations of Education in HBO’s The Wire, Season 4 By James Trier The Wire is a crime drama that aired for five seasons on the Home Box Of- fice (HBO) cable channel from 2002-2008. The entire series is set in Baltimore, Maryland, and as Kinder (2008) points out, “Each season The Wire shifts focus to a different segment of society: the drug wars, the docks, city politics, education, and the media” (p. 52). The series explores, in Lanahan’s (2008) words, an increasingly brutal and coarse society through the prism of Baltimore, whose postindustrial capitalism has decimated the working-class wage and sharply divided the haves and have-nots. The city’s bloated bureaucracies sustain the inequality. The absence of a decent public-school education or meaningful political reform leaves an unskilled underclass trapped between a rampant illegal drug economy and a vicious “war on drugs.” (p. 24) My main purpose in this article is to introduce season four of The Wire—the “education” season—to readers who have either never seen any of the series, or who have seen some of it but James Trier is an not season four. Specifically, I will attempt to show associate professor in the that season four holds great pedagogical potential for School of Education at academics in education.1 First, though, I will present the University of North examples of the critical acclaim that The Wire received Carolina at Chapel throughout its run, and I will introduce the backgrounds Hill, Chapel Hill, North of the creators and main writers of the series, David Carolina. -

Cons & Confusion

Cons & Confusion The almost accurate convention listing of the B.T.C.! We try to list every WHO event, and any SF event near Buffalo. updated: July 19, 2019 to add an SF/DW/Trek/Anime/etc. event; send information to: [email protected] 2019 DATE local EVENT NAME WHERE TYPE WEBSITE LINK JULY 18-21 NYS MISTI CON Doubletree/Hilton, Tarrytown, NY limited size Harry Potter event http://connecticon.org/ JULY 18-21 CA SAN DIEGO COMIC CON S.D. Conv. Ctr, San Diego, CA HUGE media & comics show NO DW GUESTS YET! Neal Adams, Sergio Aragones, David Brin, Greg Bear, Todd McFarlane, Craig Miller, Frank Miller, Audrey Niffenegger, Larry Niven, Wendy & Richard Pini, Kevin Smith, (Jim?) Steranko, J Michael Straczynski, Marv Wolfman, (most big-name media guests added in last two weeks or so) JULY 19-21 OH TROT CON 2019 Crowne Plaza Htl, Columbus, OH My Little Pony' & other equestrials http://trotcon.net/ Foal Papers, Elley-Ray, Katrina Salisbury, Bill Newton, Heather Breckel, Riff Ponies, Pixel Kitties, The Brony Critic, The Traveling Pony Museum JULY 19-21 KY KEN TOKYO CON Lexington Conv. Ctr, Lexington, KY anime & gaming con https://www.kentokyocon.com/ JULY 20 ONT ELMVALE SCI-FI FANTASY STREET PARTY Queen St, Elmvale, Ont (North of Lake Simcoe!) http://www.scififestival.ca/ Stephanie Bardy, Vanya Yount, Loc Nguyen, Christina & Martn Carr Hunger, Julie Campbell, Amanda Giasson JULY 20 PA WEST PA BOOK FEST Mercer High School, Mercer, PA all about books http://www.westpabookfestival.com/ Patricia Miller, Michael Prelee, Linda M Au, Joseph Max Lewis, D R Sanchez, Judy Sharer, Arlon K Stubbe, Ruth Ochs Webster, Robert Woodley, Kimberly Miller JULY 20-21 Buf WILD RENN FEST Hawk Creek Wildlife Ctr, East Aurora, NY Renn fest w/ live animals https://www.hawkcreek.org/wp/ "Immerse yourself in Hawk Creek’s unique renaissance-themed celebration of wildlife diversity! Exciting entertainment and activities for all ages includes live wildlife presentations, bird of prey flight demonstrations, medieval reenactments, educational exhibits, food, music, art, and much more! JULY 20-21 T.O. -

Tom Hanks Halle Berry Martin Sheen Brad Pitt Robert Deniro Jodie Foster Will Smith Jay Leno Jared Leto Eli Roth Tom Cruise Steven Spielberg

TOM HANKS HALLE BERRY MARTIN SHEEN BRAD PITT ROBERT DENIRO JODIE FOSTER WILL SMITH JAY LENO JARED LETO ELI ROTH TOM CRUISE STEVEN SPIELBERG MICHAEL CAINE JENNIFER ANISTON MORGAN FREEMAN SAMUEL L. JACKSON KATE BECKINSALE JAMES FRANCO LARRY KING LEONARDO DICAPRIO JOHN HURT FLEA DEMI MOORE OLIVER STONE CARY GRANT JUDE LAW SANDRA BULLOCK KEANU REEVES OPRAH WINFREY MATTHEW MCCONAUGHEY CARRIE FISHER ADAM WEST MELISSA LEO JOHN WAYNE ROSE BYRNE BETTY WHITE WOODY ALLEN HARRISON FORD KIEFER SUTHERLAND MARION COTILLARD KIRSTEN DUNST STEVE BUSCEMI ELIJAH WOOD RESSE WITHERSPOON MICKEY ROURKE AUDREY HEPBURN STEVE CARELL AL PACINO JIM CARREY SHARON STONE MEL GIBSON 2017-18 CATALOG SAM NEILL CHRIS HEMSWORTH MICHAEL SHANNON KIRK DOUGLAS ICE-T RENEE ZELLWEGER ARNOLD SCHWARZENEGGER TOM HANKS HALLE BERRY MARTIN SHEEN BRAD PITT ROBERT DENIRO JODIE FOSTER WILL SMITH JAY LENO JARED LETO ELI ROTH TOM CRUISE STEVEN SPIELBERG CONTENTS 2 INDEPENDENT | FOREIGN | ARTHOUSE 23 HORROR | SLASHER | THRILLER 38 FACTUAL | HISTORICAL 44 NATURE | SUPERNATURAL MICHAEL CAINE JENNIFER ANISTON MORGAN FREEMAN 45 WESTERNS SAMUEL L. JACKSON KATE BECKINSALE JAMES FRANCO 48 20TH CENTURY TELEVISION LARRY KING LEONARDO DICAPRIO JOHN HURT FLEA 54 SCI-FI | FANTASY | SPACE DEMI MOORE OLIVER STONE CARY GRANT JUDE LAW 57 POLITICS | ESPIONAGE | WAR SANDRA BULLOCK KEANU REEVES OPRAH WINFREY MATTHEW MCCONAUGHEY CARRIE FISHER ADAM WEST 60 ART | CULTURE | CELEBRITY MELISSA LEO JOHN WAYNE ROSE BYRNE BETTY WHITE 64 ANIMATION | FAMILY WOODY ALLEN HARRISON FORD KIEFER SUTHERLAND 78 CRIME | DETECTIVE -

Department of Political Science Chair of Gender Politics Wonder Woman

Department of Political Science Chair of Gender Politics Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel as Representation of Women in Media Sara Mecatti Prof. Emiliana De Blasio Matr. 082252 SUPERVISOR CANDIDATE Academic Year 2018/2019 1 Index 1. History of Comic Books and Feminism 1.1 The Golden Age and the First Feminist Wave………………………………………………...…...3 1.2 The Early Feminist Second Wave and the Silver Age of Comic Books…………………………....5 1.3 Late Feminist Second Wave and the Bronze Age of Comic Books….……………………………. 9 1.4 The Third and Fourth Feminist Waves and the Modern Age of Comic Books…………...………11 2. Analysis of the Changes in Women’s Representation throughout the Ages of Comic Books…..........................................................................................................................................................15 2.1. Main Measures of Women’s Representation in Media………………………………………….15 2.2. Changing Gender Roles in Marvel Comic Books and Society from the Silver Age to the Modern Age……………………………………………………………………………………………………17 2.3. Letter Columns in DC Comics as a Measure of Female Representation………………………..23 2.3.1 DC Comics Letter Columns from 1960 to 1969………………………………………...26 2.3.2. Letter Columns from 1979 to 1979 ……………………………………………………27 2.3.3. Letter Columns from 1980 to 1989…………………………………………………….28 2.3.4. Letter Columns from 19090 to 1999…………………………………………………...29 2.4 Final Data Regarding Levels of Gender Equality in Comic Books………………………………31 3. Analyzing and Comparing Wonder Woman (2017) and Captain Marvel (2019) in a Framework of Media Representation of Female Superheroes…………………………………….33 3.1 Introduction…………………………….…………………………………………………………33 3.2. Wonder Woman…………………………………………………………………………………..34 3.2.1. Movie Summary………………………………………………………………………...34 3.2.2.Analysis of the Movie Based on the Seven Categories by Katherine J. -

Parent Handbook 2020-2021

1 PERSONNEL/CLASS SCHEDULE 6 R3 Expectations 6 Philosophy 6 Student in Good Standing 8 Communication Between Home/School: Who to Call 9 Victor Junior High Faculty & Staff 10 Class Time Schedule 12 PROGRAM DESCRIPTIONS 13 Junior High Curriculum 13 Art 14 BOOST 14 English 14 Languages Other Than English 15 Health 15 Family & Consumer Science 16 Literacy Lab 16 Mathematics 16 Music 17 Physical Education 18 Science 18 Social Studies 19 Special Education 19 Technology Education 20 GUIDANCE/TESTING/PARENTING 21 Guidance/School Counseling 21 Testing 21 Parent/Teacher Conferences 21 School/Home Communication 21 Integrity Policy 22 Academic Honors 23 Awards Assembly 23 Breakfast with the Principal 23 Eligibility 23 Eligibility Guidelines 23 Homework 24 Promotional Policy 24 Report Cards 25 Study Habits 25 Study Halls 26 2 Textbooks 26 ACTIVITIES/CLUBS 26 Academic Challenge Bowl 26 Activity Nights 27 Art Club 28 Big Time Friends 28 Culinary Club 28 Fiddle Club 28 Field Band 28 French Club 28 Go Green Garden Team 28 GSA (Gay-Straight Alliance) 29 Jazz Club 29 Math Olympiad 29 Musical 29 Positive Connections Club (PCC) 29 Spanish Club 29 Student Council 29 Yearbook 30 Young Men’s Leadership 30 Young Women’s Leadership 30 Citizenship 30 Discipline Code 30 Activity Period 30 Attire 31 Backpacks 31 Electronic Devices 31 Code of Conduct 32 SERVICES 35 Cafeteria 35 Emergency Evacuation/Fire Drills 36 Library 36 Lockers 36 HEALTH SERVICES 37 School Health Office Staff 37 Confidentiality 37 Mandated Physical Exams 37 Registration for Sports 37 Mandatory -

The Authority: Earth Inferno and Other Stories V. 3 Free

FREE THE AUTHORITY: EARTH INFERNO AND OTHER STORIES V. 3 PDF Mark Millar,Frank Quitely,Chris Weston | 160 pages | 01 Aug 2002 | DC Comics | 9781563898549 | English | United States Earth Inferno for sale online | eBay This article is a list of story arcs for the Wildstorm comic book The Authority presented in chronological order of release. The Authority make their first public appearance to stop Kaizen Gamorraan old enemy of Stormwatchwho wants to take advantage of Stormwatch's breakup to take revenge upon the world. To do this he uses engineered supersoldiers to destroy first Moscow and then part of London. The Authority does not manage to stop the attack on London, then predicts the third and final attack in Los Angeles which is averted with heavy civilian casualties. Midnighter uses the Carrier to destroy the superhuman clone factory on Gamorra's island. The Authority have to stop an invasion by a parallel Earth, specifically a parallel Britain called Sliding Albion. As it turns out, Jenny Sparks has met them before when their The Authority: Earth Inferno and Other Stories v. 3 first appeared in Sliding Albion is a world where open contact between aliens the blues and humans during the 16th century led to interbreeding and an imperialist culture similar to the Victorian British Empire. After the Authority repel the initial wave of attacks, Jenny takes the Carrier to the Sliding Albion universe where they destroy London and Italy and what's left of the blues' regime along with it. In an all-frequencies message, she tells the people to take advantage of the second chance and "We are the Authority. -

Apollo Investment Corporation (“AINV” Or the “Company”) for the Fiscal Year Ended March 31, 2020

2020 ANNUAL REPORT Dear Fellow Shareholders, We are pleased to present you with the annual report for Apollo Investment Corporation (“AINV” or the “Company”) for the fiscal year ended March 31, 2020. As we write this year's letter, the world is facing both a significant health and economic crisis due to the outbreak of the novel coronavirus (“COVID-19”, “coronavirus”, or “pandemic”). We hope this letter finds you safe and in good health. In our annual shareholder letters, we typically review our results for the year and provide our outlook for the next fiscal year. In this year’s letter, we will also focus on how AINV was positioned entering this challenging period, and how we are navigating the current environment. First and foremost, on behalf of everyone at AINV, we want to express our appreciation to all those who are working tirelessly to keep us safe and maintain essential services. We offer our deepest sympathy to all those who have been affected by the coronavirus. Our priority continues to be the health and well-being of our stakeholders and the employees of the Company’s Investment Adviser, Apollo Investment Management, L.P., an affiliate of Apollo Global Management, Inc., (together with its affiliates, “Apollo Global”). Apollo has fully transitioned to a remote work environment while ensuring full business continuity. A Review of Fiscal Year 2020 Looking back at fiscal year 2020, we continued to make significant progress executing our de-risking investment strategy to prepare for potential headwinds, if not an economic downturn such as the one we are currently experiencing. -

ABSTRACT the Pdblications of the Marvel Comics Group Warrant Serious Consideration As .A Legitimate Narrative Enterprise

DOCU§ENT RESUME ED 190 980 CS 005 088 AOTHOR Palumbo, Don'ald TITLE The use of, Comics as an Approach to Introducing the Techniques and Terms of Narrative to Novice Readers. PUB DATE Oct 79 NOTE 41p.: Paper' presented at the Annual Meeting of the Popular Culture Association in the South oth, Louisville, KY, October 18-20, 19791. EDFS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage." DESCRIPTORS Adolescent Literature:,*Comics (Publications) : *Critical Aeading: *English Instruction: Fiction: *Literary Criticism: *Literary Devices: *Narration: Secondary, Educition: Teaching Methods ABSTRACT The pdblications of the Marvel Comics Group warrant serious consIderation as .a legitimate narrative enterprise. While it is obvious. that these comic books can be used in the classroom as a source of reading material, it is tot so obvious that these comic books, with great economy, simplicity, and narrative density, can be used to further introduce novice readers to the techniques found in narrative and to the terms employed in the study and discussion of a narrative. The output of the Marvel Conics Group in particular is literate, is both narratively and pbSlosophically sophisticated, and is ethically and morally responsible. Some of the narrative tecbntques found in the stories, such as the Spider-Man episodes, include foreshadowing, a dramatic fiction narrator, flashback, irony, symbolism, metaphor, Biblical and historical allusions, and mythological allusions.4MKM1 4 4 *********************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. * *********************************************************************** ) U SOEPANTMENTO, HEALD.. TOUCATiONaWELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE CIF 4 EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT was BEEN N ENO°. DOCEO EXACTLY AS .ReCeIVED FROM Donald Palumbo THE PE aSON OR ORGANIZATIONORIGuN- ATING T POINTS VIEW OR OPINIONS Department of English STATED 60 NOT NECESSARILY REPRf SENT OFFICIAL NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF O Northern Michigan University EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY CO Marquette, MI. -

Read Book 1979 in Comics: 1979 Comic Debuts, Comics Characters

[PDF] 1979 in comics: 1979 comic debuts, Comics characters introduced in 1979, Northstar, ABC Warriors, Black... 1979 in comics: 1979 comic debuts, Comics characters introduced in 1979, Northstar, ABC Warriors, Black Cat, War Machine, Doctor Who Magazine Book Review If you need to adding benefit, a must buy book. Better then never, though i am quite late in start reading this one. You will not truly feel monotony at at any time of your time (that's what catalogs are for concerning should you check with me). (K ay K irlin IV ) 1979 IN COMICS: 1979 COMIC DEBUTS, COMICS CHA RA CTERS INTRODUCED IN 1979, NORTHSTA R, A BC W A RRIORS, BLA CK CA T, W A R MA CHINE, DOCTOR W HO MA GA ZINE - To save 1979 in comics: 1979 comic debuts, Comics characters introduced in 1979, Northstar, A BC Warriors, Black Cat, War Machine, Doctor W ho Mag azine eBook, make sure you refer to the hyperlink listed below and save the file or gain access to other information which are related to 1979 in comics: 1979 comic debuts, Comics characters introduced in 1979, Northstar, ABC Warriors, Black Cat, War Machine, Doctor Who Magazine ebook. » Download 1979 in comics: 1979 comic debuts, Comics characters introduced in 1979, Northstar, A BC W arriors, Black Cat, W ar Machine, Doctor W ho Mag azine PDF « Our web service was introduced having a hope to work as a full online electronic digital local library that offers usage of large number of PDF e-book assortment. You could find many kinds of e-publication and other literatures from our files database. -

Truth, Justice, and the Canadian Way: the War-Time Comics of Bell Features Publications Ivan Kocmarek Hamilton, Ontario

Truth, Justice, and the Canadian Way: The War-Time Comics of Bell Features Publications Ivan Kocmarek Hamilton, Ontario 148 What might be called the “First Age of Canadian Comics”1 began on a consum- mately Canadian political and historical foundation. Canada had entered the Second World War on September 10, 1939, nine days after Hitler invaded the Sudetenland and a week after England declared war on Germany. Just over a year after this, on December 6, 1940, William Lyon MacKenzie King led parliament in declaring the War Exchange Conservation Act (WECA) as a protectionist measure to bolster the Canadian dollar and the war economy in general. Among the paper products now labeled as restricted imports were pulp magazines and comic books.2 Those precious, four-colour, ten-cent treasure chests of American culture that had widened the eyes of youngsters from Prince Edward to Vancouver Islands immedi- ately disappeared from the corner newsstands. Within three months—indicia dates give March 1941, but these books were probably on the stands by mid-January— Anglo-American Publications in Toronto and Maple Leaf Publications in Vancouver opportunistically filled this vacuum by putting out the first issues of Robin Hood Comics and Better Comics, respectively. Of these two, the latter is widely considered by collectors to be the first true Canadian comic book becauseRobin Hood Comics Vol. 1 No. 1 seems to have been a tabloid-sized collection of reprints of daily strips from the Toronto Telegram written by Ted McCall and drawn by Charles Snelgrove. Still in Toronto, Adrian Dingle and the Kulbach twins combined forces to release the first issue of Triumph-Adventure Comics six months later (August 1941), and then publisher Cyril Bell and his artist employee Edmund T.