Peaks & Glaciers 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trip Factsheet: Piz Bernina Ski Tour the Piz Bernina Overlooks The

Trip Factsheet: Piz Bernina Ski Tour The Piz Bernina overlooks the Engardine valley in Switzerland and despite its proximity to the glitzy resort of St. Moritz the ski touring is quiet and unspoiled. It covers some challenging terrain and dramatic scenery with some big days out at altitude for the avid ski tourer. Travel to and from Silvaplana The closest airport is Zurich. Transfer time to Silvaplana by rail is about 4 hours 15 mins. For train timetables and fares please look at www.sbb.ch/en You want to arrange to arrive in Silvaplana by late afternoon on the Saturday. At the end of the week the tour finishes after breakfast on the second Saturday and we recommend that you arrange your return/onward flight for mid/late afternoon to give yourself plenty of time to get to the airport without having to rush! Want to take the train to the resort? No problem – it’s possible to get to St. Moritz by train from the UK using the Eurostar from London St. Pancras to Paris, then the TGV to Basel and onward via regional train. The journey can be done in 1 day. For more information and other useful train travel details look at www.snowcarbon.co.uk Swiss Transfer Ticket - this is a return ticket from the Swiss boarder or one of Switzerland's airports to your destination. The ticket is valid for 1 month, but each journey must be completed in one day and on the most direct route. The transfer ticket cannot be brought in Switzerland you must do it in advance from a sales point like the Switzerland Travel Centre in London. -

Courmayeur Val Ferret Val Veny La Thuile Pré-Saint-Didier Morgex La

Sant’Orso fair Sankt Orso-Messe Matterhorn Tourist Courmayeur Mont Blanc Office Aosta roman and Val Ferret medieval town Monte Rosa Tourismusbüro Aosta römische und Val Veny mittelalterliche Stadt Astronomic observatory La Thuile Astronomische Observatorium Courmayeur Piazzale Monte Bianco, 13 Pré-Saint-Didier C E R V I N O 11013 Courmayeur AO Tel (+39) 0165 842060 Morgex M O N T E Fax (+39) 0165 842072 A N C O Breuil-Cervinia R O B I Col / Tunnel du S La Salle E A [email protected] T Tunnel du Grand-Saint-Bernard N O Mont-Blanc M Valtournenche Gressoney La Thuile La Trinité St-Rhémy-en-Bosses étroubles Via M. Collomb, 36 Ayas Courmayeur Valpelline 11016 La Thuile AO Gressoney-St-Jean Tel (+39) 0165 884179 Pré-Saint-Didier St-Barthélemy AOSTA Châtillon Brusson Fax (+39) 0165 885196 Sarre dalle flavio [email protected] • La Thuile Col du Fénis St-Vincent Petit-Saint-Bernard Pila VIC T A N guide società O • M L Verrès E D O Issogne C Cogne R A Valgrisenche P Bard Office Régional Champorcher Valsavarenche du Tourisme Rhêmes-Notre-Dame O DIS P A A AR Pont-St-Martin R N P Ufficio Regionale CO RA NAZIONALE G del Turismo Torino turistici operatori consorzi • Milano V.le Federico Chabod, 15 Genova G 11100 Aosta R A O Spas N P A R A D I S Therme 360° view over the whole chain of the Alps Gran Paradiso 360° Aussicht auf die gesamte Alpenkette Fénis (1), Issogne (2), Verrès (3), www.lovevda.it Traverse of Mont Sarre (4) castles and Blanc Bard Fortress (5) Überquerung des Schlösser Fénis (1), Issogne (2) Mont Blanc Verrès (3) und Bard -

Guide Hiver 2020-2021

BIENVENUE WELCOME GUIDE VALLÉE HIVER 2020-2021 WINTER VALLEY GUIDE SERVOZ - LES HOUCHES - CHAMONIX-MONT-BLANC - ARGENTIÈRE - VALLORCINE CARE FOR THE INDEX OCEAN* INDEX Infos Covid-19 / Covid information . .6-7 Bonnes pratiques / Good practice . .8-9 SERVOZ . 46-51 Activités plein-air / Open-air activities ����������������� 48-49 FORFAITS DE SKI / SKI PASS . .10-17 Culture & Détente / Culture & Relaxation ����������� 50-51 Chamonix Le Pass ��������������������������������������������������������������������� 10-11 Mont-Blanc Unlimited ������������������������������������������������������������� 12-13 LES HOUCHES . 52-71 ��������������������������������������������� Les Houches ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 14-15 Ski nordique & raquettes 54-55 Nordic skiing & snowshoeing DOMAINES SKIABLES / SKI AREAS �����������������������18-35 Activités plein-air / Open-air activities ����������������� 56-57 Domaine des Houches . 18-19 Activités avec les animaux ����������������������������������������� 58-59 Le Tourchet ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 20-21 Activities with animals Le Brévent - La Flégère . 22-25 Activités intérieures / Indoor activities ����������������� 60-61 Les Planards | Le Savoy ��������������������������������������������������������� 26-27 Guide des Enfants / Children’s Guide . 63-71 Les Grands Montets ����������������������������������������������������������������� 28-29 Famille Plus . 62-63 Les Chosalets | La Vormaine ����������������������������������������������� -

Matterhorn Guided Ascent Ex Zermatt 2021

MATTERHORN 4,478M / 14,691FT EX ZERMATT 2021 TRIP NOTES MATTERHON EX ZERMATT TRIP NOTES 2021 TRIP DETAILS Dates: Available on demand July to September Duration: 6 days Departure: ex Zermatt, Switzerland Price: €5,870 per person A classic ‘must-do’ European climb. Photo: Mike Roberts The Matterhorn is undeniably the most magnificent and well-known peak in the Alps. Its bold pyramidal shape evokes emotions of wonderment and even fear in those who view it for the first time, as its four distinct faces stand omnipotent and menacing over the green meadows below. Separated by sharp ridges, the four faces are orientated to the four points of the compass, the northern aspects within Switzerland while the southern side lies in Italy. We ascend via the Hörnli Ridge that separates the rich heritage adds to the superb facilities, including North and East Faces via a long and technical route catered huts and lift systems offering services not requiring the utmost attention from climbers. The seen elsewhere. steep rock ridge is very involving and a successful attempt requires a rapid rate of ascent and full The Hörnli Ridge is the route by which the concentration by a fit party. The steep North and Matterhorn’s first ascent was made in 1865 by the East Faces drop away spectacularly on either side tenacious Englishman, Edward Whymper, after and the sense of exposure is dramatic. many attempts on the mountain. In what became the most famous alpine calamity of all time, the With its formidable history and the magnificent group suffered a terrible tragedy on the descent grandeur of its architecture, the Hörnli Ridge on when a rope broke resulting in the loss of four of the Matterhorn is a climb that is definitely worth the party. -

Ortsplan Täsch Und Randa

48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 DE FR EN Legende / Légende / Caption Täschalp Täschalp ORTSPLAN RANDA & TÄSCH. Hotels & Restaurants PLAN DE VILLAGE. p äschal Sportanlagen / Terrains de sport / Sport Facilities M T M VILLAGE MAP. Bahnen / Remontées mécaniques / Mountain Transport Facilities Bushaltestelle / Arrêt d’autobus / Bus Stop EINZIGARTIG IDYLLISCH NatURBELASSEN Täschalp VIELFÄltig N Täschalpstrasse N ÄGERTA 5173 ENSOLEILLÉ CHUMMA 5016 5092 5166 VariÉ 5126 5169 5170 5108 5045 EXCELLENT nach Randa 5109 BINGÄSSI 5070 5143 5080 5175 TRADITIONAL 5153 5035 5104 5072 5041 5075 HINNER SUstainaBLE O nach Randa 5138 O 5060 5174 5154 TÄSCH HOF ZER BLATTLI 5131 5146 CUltURAL 5136 5071 5142 5101 5151 5100 5065 5020 5185 5223 5062 5224 5158 5137 5152 HERWÄG WERI 5038 5150 5091 5077 Oberdorfstr5014. 5155 5040 5012 5011 5160 5106 5107 5007 5098 5030 5141 5177 5111 5129 Alte Kantonsstrasse 5149 5033 5076 5017 5128 5167 5165 5099 5029 5088 5034 5124 5018 5102 51715056 5001 5221 5159 5157 5178 DERFJI 5027 5145 5135 5090 5214 5046 5079 5087 5214 5118 5026 5068 5074 P 5039 5134 nach Zermatt P 5089 5216 5183 5176 5205 5028 5013 5024 TAXI TAXI 5010 5148 5004 5078 zermatt.ch 5044 5183 5163 5043 5147 5057 5164 5003 5025 5110 Golf Club Matterhorn Golf Club Matterhorn 5220 5156 5182 5031 5132 5162 EYA 5019 5073 5121 5061 5181 5067 5206 5006 5086 ÜSSERS SAND 5113 5114 5115 5032 5008 5103 LÖUCHA 5117 5180 Langl 5081 5140 5139 5112 5066 TAXI 5211 TÄSCH- 5179 aufloipe 5069 5125 5085 5123 5058 5002 5050 5084 MATTA UNIQUE MOMENTS 5105 TAXI 5095 Vispa 5047 5223 5120 5015 5083 5215 5116 5009 5094 ALL YEAR ROUND IN TAXI 5172 5005 5055 Q Schalisee 5213 52105202 rasse Q Langlaufloipe Golf IM BRU ZERMATT – MATTERHORN. -

“Darkening Swiss Glacier Ice?” by Kathrin Naegeli Et Al

The Cryosphere Discuss., https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-2018-18-AC2, 2018 TCD © Author(s) 2018. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Interactive comment Interactive comment on “Darkening Swiss glacier ice?” by Kathrin Naegeli et al. Kathrin Naegeli et al. [email protected] Received and published: 17 April 2018 ——————————————————————————— We would like to thank the referee 2 for this careful and detailed review. We appreciate the in-depth comments and are convinced that thanks to the respective changes, the manuscript will improve substantially. In response to this review, we elaborated the role of supraglacial debris in more detail by: (1) manually delineating medial moraines and areas where tributaries separated from the main glacier trunk and debris has become exposed to obtain a complete Printer-friendly version supraglacial debris mask based on the Sentinel-2 image acquired in August 2016, and (2) applying this debris mask to all data and, thus, to exclude areas with debris cover- Discussion paper age from all consecutive analyses. Additionally, we further developed the uncertainty assessment of the retrieved albedo values by providing more information about the C1 datasets used as well as their specific constraints and uncertainties that may result thereof in a separate sub-section in the methods section. Based on these revisions, TCD the conclusions will most likely be slightly adjusted, however, stay in line with the orig- inal aim of our study to investigate possible changes in bare-ice albedo in the Swiss Alps based on readily available Landsat surface reflectance data. Interactive comment Below we respond to all comments by anonymous referee 2. -

4000 M Peaks of the Alps Normal and Classic Routes

rock&ice 3 4000 m Peaks of the Alps Normal and classic routes idea Montagna editoria e alpinismo Rock&Ice l 4000m Peaks of the Alps l Contents CONTENTS FIVE • • 51a Normal Route to Punta Giordani 257 WEISSHORN AND MATTERHORN ALPS 175 • 52a Normal Route to the Vincent Pyramid 259 • Preface 5 12 Aiguille Blanche de Peuterey 101 35 Dent d’Hérens 180 • 52b Punta Giordani-Vincent Pyramid 261 • Introduction 6 • 12 North Face Right 102 • 35a Normal Route 181 Traverse • Geogrpahic location 14 13 Gran Pilier d’Angle 108 • 35b Tiefmatten Ridge (West Ridge) 183 53 Schwarzhorn/Corno Nero 265 • Technical notes 16 • 13 South Face and Peuterey Ridge 109 36 Matterhorn 185 54 Ludwigshöhe 265 14 Mont Blanc de Courmayeur 114 • 36a Hörnli Ridge (Hörnligrat) 186 55 Parrotspitze 265 ONE • MASSIF DES ÉCRINS 23 • 14 Eccles Couloir and Peuterey Ridge 115 • 36b Lion Ridge 192 • 53-55 Traverse of the Three Peaks 266 1 Barre des Écrins 26 15-19 Aiguilles du Diable 117 37 Dent Blanche 198 56 Signalkuppe 269 • 1a Normal Route 27 15 L’Isolée 117 • 37 Normal Route via the Wandflue Ridge 199 57 Zumsteinspitze 269 • 1b Coolidge Couloir 30 16 Pointe Carmen 117 38 Bishorn 202 • 56-57 Normal Route to the Signalkuppe 270 2 Dôme de Neige des Écrins 32 17 Pointe Médiane 117 • 38 Normal Route 203 and the Zumsteinspitze • 2 Normal Route 32 18 Pointe Chaubert 117 39 Weisshorn 206 58 Dufourspitze 274 19 Corne du Diable 117 • 39 Normal Route 207 59 Nordend 274 TWO • GRAN PARADISO MASSIF 35 • 15-19 Aiguilles du Diable Traverse 118 40 Ober Gabelhorn 212 • 58a Normal Route to the Dufourspitze -

Lithostratigraphy and U-Pb Zircon Dating in the Overturned Limb of the Siviez-Mischabel Nappe: a New Key for Middle Penninic Nappe Geometry

1661-8726/08/020431-22 Swiss J. Geosci. 101 (2008) 431–452 DOI 10.1007/s00015-008-1261-5 Birkhäuser Verlag, Basel, 2008 Lithostratigraphy and U-Pb zircon dating in the overturned limb of the Siviez-Mischabel nappe: a new key for Middle Penninic nappe geometry FLORIAN GENIER1, JEAN-LUC EPARD 1, FRANÇOIS BUSSY 2 & TOMAS MAGNA2 Key words: alps, Middle Penninic, Siviez-Mischabel nappe, Permo-Carboniferous, Randa orthogneiss, zircon typology, U-Pb geochronology ABSTRACT Detailed field work and zircon analysis have improved the knowledge of the This coherent overturned sequence can be observed from the St-Niklaus area to lithostratigraphy at the base of the Siviez-Mischabel nappe in the Mattertal the Moosalp pass to the north. Detailed mapping revealed that the St-Niklaus (St-Niklaus-Törbel area). They confirm the existence of an overturned limb syncline is symmetrical and connects the overturned limb of the Siviez-Mischa- and clarify the structure of the St-Niklaus syncline. The following formations bel nappe to the normal series of the Upper Stalden zone. U-Pb zircon geo- can be observed: chronology on magmatic and detrital zircons allowed constraining ages of these formations. Detrital zircons display ages ranging from 2900 ± 50 to 520 ± 4 Ma • Polymetamorphic gneisses; composed of paragneisses, amphibolites and in the Törbel Formation, and from 514 ± 6 to 292 ± 9 Ma in the Moosalp Forma- micaschists (Bielen Unit, pre-Ordovician). tion. In addition, the Permian Randa orthogneiss is intrusive into the polymeta- • Fine-grained, greyish quartzite and graywacke with kerogen-rich hori- morphic gneisses and into the Permo-Carboniferous metasediments of the zons (Törbel Formation, presumed Carboniferous). -

![Viertausender Wallis[1].Docx](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5423/viertausender-wallis-1-docx-325423.webp)

Viertausender Wallis[1].Docx

Viertausender Sammeln im Wallis Viertausender Sammeln im Wallis Die Überschreitung des Walliser Grenzkamms vom Breithorn bis zum Monte-Rosa-Stock ist eine phantastische und nicht allzu schwierige Hochtour, bei der ein Viertausender dem anderen folgt. Nach einem gemütlichen Start mit Allalinhorn und Talstützpunkt geht es dann für 5 Tage weg von der Zivilisation! Untergebracht werden wir auf gut geführten, aber natürlcih eher funktionellen Westalpen Hütten. Frühzeitige Buchung notwendig! Gebiet: Wallis/ Zermatt Viertausender Sammeln im Wallis Termin: 29. Juli – 04. August 2012 Bei einer Gruppengröße von 4 Personen ist auch individuelle Terminvereinbarung möglich. Programm: 1. Tag: Anreise. Treffpunkt um 18:00 im Hotel in Herbriggen im Mattertal. 2. Tag: Allalinhorn, 4026 m. Akklimatisationstour. Nach Auffahrt mit der Seilbahn zum Mittel-Allalin, 3454 m, Aufstieg über das Feejoch zum Allalinhorn. Am Gipfel steht man mitten in der Welt der Walliser Viertausender: Auf der einen Seite erhebt sich die mächtige Eis- und Felsmauer der Mischabelgruppe, auf der anderen Seite der Monte Rosa und das Matterhorn. 3. Tag: Auffahrt von Zermatt zum Klein Matterhorn - Breithorn, 4159 m - Rifugio Guide della Valle d´Ayas, 3420 m. Ein weiterer nicht all zu langer Tag zum Akklimatisieren in der 4000er- Region mit traumhaften Ausblicken auf die norditalienische Tiefebene und die umliegenden hohen Berge des Wallis. 4. Tag: Castor, 4228 m - Rifugio Quintino Sella, 3585 m. Zwar kein langer Tag, aber dafür mit einer ausgesetzten Gratpassage hinauf zum Gipfel des Castor. 5. Tag: Naso di Lys (4272m) - Vincentpyramide, 4215 m – Rifugio Citta di Mantova, 3470 m. Die „Schlüsselpassage“ mit einer kurzen Steilflanke erfordert konzentriertes Steigen. 6. Tag: Corno Nero (4321m) - Ludwigshöhe (4343m) - Parrotspitze, 4432 m - Signalkuppe, 4554 m - Capanna Margherita, 4559 m. -

Sphaleroptera Alpicolana (FRÖLICH 1830) (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae, Cnephasiini): a Species Complex

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Veröffentlichungen des Tiroler Landesmuseums Ferdinandeum Jahr/Year: 2006 Band/Volume: 86 Autor(en)/Author(s): Whitebread Steven Artikel/Article: Sphaleroptera alpicolana (FRÖLICH 1830) (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae, Cnephasiini): a species complex. 177-204 © Tiroler Landesmuseum Ferdinandeum, Innsbruck download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Veröffentlichungen des Tiroler Landesmuseums Ferdinandeum 86/2006 Innsbruck 2006 177-204 Sphaleroptera alpicolana (FRÖLICH 1830) (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae, Cnephasiini): a species complex Steven Whitebread Sphaleroptera alpicolana (FRÖLICH 1830) (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae, Cnephasiini): Ein Spezies Komplex Summary Sphaleroptera alpicolana (FRÖLICH 1830) is a locally common day-flying high Alpine species previously considered to oeeur in the German, Austrian, Swiss, Italian and French Alps, and the Pyrenees. The females have reduced wings and cannot fly. However, a study of material from the known ränge of the species has shown that "Sphaleroptera alpi- colana" is really a complex of several taxa. S. alpicolana s.str. oecurs in the central part of the Alps, in Switzerland, Italy, Austria and Germany. A new subspecies, S. a. buseri ssp.n. is described from the Valais (Switzerland). Four new species are described, based on distinet differences in the male and female genitalia: S. occiclentana sp.n., S. adamel- loi sp.n.. S. dentana sp.n. and .S'. orientana sp.n., with the subspecies S. o. suborientana. Distribution maps are giv- en for all taxa and where known, the early stages and life histories are described. The role of the Pleistocene glacia- tions in the speciation process is discussed. Zusammenfassung Sphaleroptera alpicolana (FRÖLICH 1830) ist eine lokal häufige, Tag fliegende, hochalpine Art, bisher aus den deut- schen, österreichischen, schweizerischen, italienischen und französischen Alpen, und den Pyrenäen bekannt. -

In Memoriam 115

IN MEMORIAM 115 • IN MEMORIAM CLAUDE WILSON 1860-1937 THE death of Claude Wilson within a few weeks of attaining his seventy-seventh birthday came as a terrible shock to his many friends. Few of us even knew that he was ill, but in the manner of his passing none can regret that there was no lingering illness. We can but quote his own words in Lord Conway's obituary: 'the best we can wish for those that we love is that they may be spared prolonged and hopeless ill health.' His brain remained clear up to the last twenty-four hours and he suffered no pain. The end occurred on October 31. With Claude Wilson's death an epoch of mountaineering comes to an end. He was of those who made guideless and Alpine history from Montenvers in the early 'nineties, of whom but Collie, Kesteven, Bradby, ~olly and Charles Pasteur still survive. That school, in which Mummery and Morse were perhaps the most prominent examples, was not composed of specialists. Its members had learnt their craft under the best Valais and Oberland guides; they were equally-proficient on rocks or on snow. It mattered little who was acting as leader in the ascent or last man in the descent. They were prepared to turn back if conditions or weather proved unfavourable. They took chances as all mountaineers are forced to do at times but no fatal accidents, no unfortunate incidents, marred that great page of Alpine history, a page not confined to Mont Blanc alone but distributed throughout the Western Alps. -

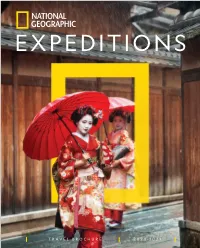

2 0 2 0–2 0 2 1 T R Av E L B R O C H U

2020–2021 R R ES E VE O BROCHURE NL INEAT VEL A NATGEOEXPE R T DI T IO NS.COM NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC EXPEDITIONS NORTH AMERICA EURASIA 11 Alaska: Denali to Kenai Fjords 34 Trans-Siberian Rail Expedition 12 Canadian Rockies by Rail and Trail 36 Georgia and Armenia: Crossroads of Continents 13 Winter Wildlife in Yellowstone 14 Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks EUROPE 15 Grand Canyon, Bryce, and Zion 38 Norway’s Trains and Fjords National Parks 39 Iceland: Volcanoes, Glaciers, and Whales 16 Belize and Tikal Private Expedition 40 Ireland: Tales and Treasures of the Emerald Isle 41 Italy: Renaissance Cities and Tuscan Life SOUTH AMERICA 42 Swiss Trains and the Italian Lake District 17 Peru Private Expedition 44 Human Origins: Southwest France and 18 Ecuador Private Expedition Northern Spain 19 Exploring Patagonia 45 Greece: Wonders of an Ancient Empire 21 Patagonia Private Expedition 46 Greek Isles Private Expedition AUSTRALIA AND THE PACIFIC ASIA 22 Australia Private Expedition 47 Japan Private Expedition 48 Inside Japan 50 China: Imperial Treasures and Natural Wonders AFRICA 52 China Private Expedition 23 The Great Apes of Uganda and Rwanda 53 Bhutan: Kingdom in the Clouds 24 Tanzania Private Expedition 55 Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia: 25 On Safari: Tanzania’s Great Migration Treasures of Indochina 27 Southern Africa Safari by Private Air 29 Madagascar Private Expedition 30 Morocco: Legendary Cities and the Sahara RESOURCES AND MORE 31 Morocco Private Expedition 3 Discover the National Geographic Difference MIDDLE EAST 8 All the Ways to Travel with National Geographic 32 The Holy Land: Past, Present, and Future 2 +31 (0) 23 205 10 10 | TRAVELWITHNATGEO.COM For more than 130 years, we’ve sent our explorers across continents and into remote cultures, down to the oceans’ depths, and up the highest mountains, in an effort to better understand the world and our relationship to it.