HEMOLYTIC ANEMIA in DISORDERS of REO CELL METABOLISM TOPICS in HEMATOLOGY Series Editor: Maxwell M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Centometabolic® COMBINING GENETIC and BIOCHEMICAL TESTING for the FAST and COMPREHENSIVE DIAGNOSTIC of METABOLIC DISORDERS

CentoMetabolic® COMBINING GENETIC AND BIOCHEMICAL TESTING FOR THE FAST AND COMPREHENSIVE DIAGNOSTIC OF METABOLIC DISORDERS GENE ASSOCIATED DISEASE(S) ABCA1 HDL deficiency, familial, 1; Tangier disease ABCB4 Cholestasis, progressive familial intrahepatic 3 ABCC2 Dubin-Johnson syndrome ABCD1 Adrenoleukodystrophy; Adrenomyeloneuropathy, adult ABCD4 Methylmalonic aciduria and homocystinuria, cblJ type ABCG5 Sitosterolemia 2 ABCG8 Sitosterolemia 1 ACAT1 Alpha-methylacetoacetic aciduria ADA Adenosine deaminase deficiency AGA Aspartylglucosaminuria AGL Glycogen storage disease IIIa; Glycogen storage disease IIIb AGPS Rhizomelic chondrodysplasia punctata, type 3 AGXT Hyperoxaluria, primary, type 1 ALAD Porphyria, acute hepatic ALAS2 Anemia, sideroblastic, 1; Protoporphyria, erythropoietic, X-linked ALDH4A1 Hyperprolinemia, type II ALDOA Glycogen storage disease XII ALDOB Fructose intolerance, hereditary ALG3 Congenital disorder of glycosylation, type Id ALPL Hypophosphatasia, adult; Hypophosphatasia, childhood; Hypophosphatasia, infantile; Odontohypophosphatasia ANTXR2 Hyaline fibromatosis syndrome APOA2 Hypercholesterolemia, familial, modifier of APOA5 Hyperchylomicronemia, late-onset APOB Hypercholesterolemia, familial, 2 APOC2 Hyperlipoproteinemia, type Ib APOE Sea-blue histiocyte disease; Hyperlipoproteinemia, type III ARG1 Argininemia ARSA Metachromatic leukodystrophy ARSB Mucopolysaccharidosis type VI (Maroteaux-Lamy) 1 GENE ASSOCIATED DISEASE(S) ASAH1 Farber lipogranulomatosis; Spinal muscular atrophy with progressive myoclonic epilepsy -

6 the Glycogen Storage Diseases and Related Disorders

6 The Glycogen Storage Diseases and Related Disorders G. Peter A. Smit, Jan Peter Rake, Hasan O. Akman, Salvatore DiMauro 6.1 The Liver Glycogenoses – 103 6.1.1 Glycogen Storage Disease Type I (Glucose-6-Phosphatase or Translocase Deficiency) – 103 6.1.2 Glycogen Storage Disease Type III (Debranching Enzyme Deficiency) – 108 6.1.3 Glycogen Storage Disease Type IV (Branching Enzyme Deficiency) – 109 6.1.4 Glycogen Storage Disease Type VI (Glycogen Phosphorylase Deficiency) – 111 6.1.5 Glycogen Storage Disease Type IX (Phosphorylase Kinase Deficiency) – 111 6.1.6 Glycogen Storage Disease Type 0 (Glycogen Synthase Deficiency) – 112 6.2 The Muscle Glycogenoses – 112 6.2.1 Glycogen Storage Disease Type V (Myophosphorylase Deficiency) – 113 6.2.2 Glycogen Storage Disease Type VII (Phosphofructokinase Deficiency) – 113 6.2.3 Phosphoglycerate Kinase Deficiency – 114 6.2.4 Glycogen Storage Disease Type X (Phosphoglycerate Mutase Deficiency) – 114 6.2.5 Glycogen Storage Disease Type XII (Aldolase A Deficiency) – 114 6.2.6 Glycogen Storage Disease Type XIII (E-Enolase Deficiency) – 115 6.2.7 Glycogen Storage Disease Type XI (Lactate Dehydrogenase Deficiency) – 115 6.2.8 Muscle Glycogen Storage Disease Type 0 (Glycogen Synthase Deficiency) – 115 6.3 The Generalized Glycogenoses and Related Disorders – 115 6.3.1 Glycogen Storage Disease Type II (Acid Maltase Deficiency) – 115 6.3.2 Danon Disease – 116 6.3.3 Lafora Disease – 116 References – 116 102 Chapter 6 · The Glycogen Storage Diseases and Related Disorders Glycogen Metabolism Glycogen is a macromolecule composed of glucose viding glucose and glycolytic intermediates (. Fig. 6.1). units. -

Clinical Consequences of Enzyme Deficiencies in the Erythrocyte

ANNALS OF CLINICAL AND LABORATORY SCIENCE, Vol. 10, No. 5 Copyright © 1980, Institute for Clinical Science, Inc. Clinical Consequences of Enzyme Deficiencies in the Erythrocyte MICHAEL L. NETZLOFF, M.D. Department of Pediatrics and Human Development, Michigan State University College of Human Medicine, East Lansing, Ml 48824 ABSTRACT The anueleate mature erythrocyte also lacks ribosomes and mitochondria and thus cannot synthesize enzymes or derive energy from the Krebs citric acid cycle. Nevertheless, the red blood cell is metabolically active and contains numerous residual enzymes and their products which are essential for its survival and normal functioning. Enzyme deficiencies in the Embden-Myerhoff glycolytic pathway can result in nonspherocytic hemoly tic anemia (NSHA), and some are also associated with neuromuscular or neurologic disorders. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency in the hexose monophosphate shunt also results in hemolytic anemia, espe cially following exposure to various drugs. Defects in glutathione synthesis and pyrimidine 5'-nucleotidase deficiency also cause NSHA, as does in creased adenosine deaminase activity. Glutathione synthetase deficiency which is not limited to the red cell also presents as oxoprolinuria with neurologic signs. All red cell enzyme defects appear as single gene errors, in most cases recessive in inheritance, either autosomal or X-linked. Clinical Consequences of Enzyme tains over 40 different enzymes, many of Deficiencies in the Erythrocyte which are essential for its survival or nor mal functioning. The purpose of this re Prior to maturity, the nucleated red port is to review some inherited enzyme blood cell (rbc) can perform a variety of deficiencies of the erythrocyte which metabolic functions, including active en compromise its viability in the circulation zyme synthesis. -

Metabolic Myopathies of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio, 8300 Floyd Curl Alejandro Tobon, MD Drive, San Antonio, TX, 78229, [email protected]

Review Article Address correspondence to Dr Alejandro Tobon, University Metabolic Myopathies of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio, 8300 Floyd Curl Alejandro Tobon, MD Drive, San Antonio, TX, 78229, [email protected]. Relationship Disclosure: Dr Tobon reports no disclosure. ABSTRACT Unlabeled Use of Purpose of Review: The metabolic myopathies result from inborn errors of Products/Investigational metabolism affecting intracellular energy production due to defects in glycogen, Use Disclosure: Dr Tobon reports no disclosure. lipid, adenine nucleotides, and mitochondrial metabolism. This article provides an * 2013, American Academy overview of the most common metabolic myopathies. of Neurology. Recent Findings: Our knowledge of metabolic myopathies has expanded rapidly in recent years, providing us with major advances in the detection of genetic and biochemical defects. New and improved diagnostic tools are now available for some of these disorders, and targeted therapies for specific biochemical deficits have been developed (ie, enzyme replacement therapy for acid maltase deficiency). Summary: The diagnostic approach for patients with suspected metabolic myopathy should start with the recognition of a static or dynamic pattern (fixed versus exercise-induced weakness). Individual presentations vary according to age of onset and the severity of each particular biochemical dysfunction. Additional clinical clues include the presence of multisystem disease, family history, and laboratory characteristics. Appropriate investigations, timely -

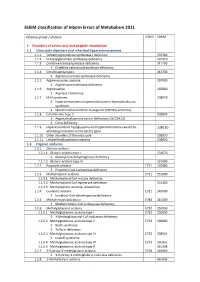

SSIEM Classification of Inborn Errors of Metabolism 2011

SSIEM classification of Inborn Errors of Metabolism 2011 Disease group / disease ICD10 OMIM 1. Disorders of amino acid and peptide metabolism 1.1. Urea cycle disorders and inherited hyperammonaemias 1.1.1. Carbamoylphosphate synthetase I deficiency 237300 1.1.2. N-Acetylglutamate synthetase deficiency 237310 1.1.3. Ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency 311250 S Ornithine carbamoyltransferase deficiency 1.1.4. Citrullinaemia type1 215700 S Argininosuccinate synthetase deficiency 1.1.5. Argininosuccinic aciduria 207900 S Argininosuccinate lyase deficiency 1.1.6. Argininaemia 207800 S Arginase I deficiency 1.1.7. HHH syndrome 238970 S Hyperammonaemia-hyperornithinaemia-homocitrullinuria syndrome S Mitochondrial ornithine transporter (ORNT1) deficiency 1.1.8. Citrullinemia Type 2 603859 S Aspartate glutamate carrier deficiency ( SLC25A13) S Citrin deficiency 1.1.9. Hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia and hyperammonemia caused by 138130 activating mutations in the GLUD1 gene 1.1.10. Other disorders of the urea cycle 238970 1.1.11. Unspecified hyperammonaemia 238970 1.2. Organic acidurias 1.2.1. Glutaric aciduria 1.2.1.1. Glutaric aciduria type I 231670 S Glutaryl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency 1.2.1.2. Glutaric aciduria type III 231690 1.2.2. Propionic aciduria E711 232000 S Propionyl-CoA-Carboxylase deficiency 1.2.3. Methylmalonic aciduria E711 251000 1.2.3.1. Methylmalonyl-CoA mutase deficiency 1.2.3.2. Methylmalonyl-CoA epimerase deficiency 251120 1.2.3.3. Methylmalonic aciduria, unspecified 1.2.4. Isovaleric aciduria E711 243500 S Isovaleryl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency 1.2.5. Methylcrotonylglycinuria E744 210200 S Methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase deficiency 1.2.6. Methylglutaconic aciduria E712 250950 1.2.6.1. Methylglutaconic aciduria type I E712 250950 S 3-Methylglutaconyl-CoA hydratase deficiency 1.2.6.2. -

BLOOD RESEARCH June 2017 ARTICLE

VOLUME 52ㆍNUMBER 2 REVIEW BLOOD RESEARCH June 2017 ARTICLE Diagnostic approaches for inherited hemolytic anemia in the genetic era Yonggoo Kim, Joonhong Park, Myungshin Kim Department of Laboratory Medicine, Catholic Genetic Laboratory Center, Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea p-ISSN 2287-979X / e-ISSN 2288-0011 Abstract https://doi.org/10.5045/br.2017.52.2.84 Inherited hemolytic anemias (IHAs) are genetic diseases that present with anemia Blood Res 2017;52:84-94. due to the increased destruction of circulating abnormal RBCs. The RBC abnor- malities are classified into the three major disorders of membranopathies, hemo- Received on March 8, 2017 globinopathies, and enzymopathies. Traditional diagnosis of IHA has been per- Revised on May 24, 2017 formed via a step-wise process combining clinical and laboratory findings. Accepted on May 25, 2017 Nowadays, the etiology of IHA accounts for germline mutations of the respon- sible genes coding for the structural components of RBCs. Recent advances in molecular technologies, including next-generation sequencing, inspire us to ap- Correspondence to ply these technologies as a first-line approach for the identification of potential Myungshin Kim, M.D., Ph.D. mutations and to determine the novel causative genes in patients with IHAs. We Department of Laboratory Medicine, Seoul herein review the concept and strategy for the genetic diagnosis of IHAs and pro- St. Mary’s Hospital, College of Medicine, vide an overview of the preparations for clinical applications of the new molecular The Catholic University of Korea, 222 Banpo-daero, Seocho-gu, Seoul 06591, technologies. -

Glycogen Storage Diseases the Patient-Parent Handbook

Glycogen Storage Diseases The Patient-Parent Handbook AGSD’s “Glycogen Storage Diseases: A Patient-Parent Handbook” TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1 The Biochemistry of Glycogen Storage Disease ………………………………………………3 Chapter 2 Important Terms …………………………………………………………………………….…………….7 Chapter 3 Glycogen Storage Diseases ……………………………………………………………………………11 Chapter 4 Type I Glycogen Storage Disease ………………………………………………………………...…13 Chapter 5 Type II Glycogen Storage Disease (abbreviated GSD II) …………………………………..21 Chapter 6 Type III Glycogen Storage Disease (abbreviated GSD III) ………………………………..25 Chapter 7 Type IV Glycogen Storage Disease (abbreviated GSD IV) ………………………………..28 Chapter 8 McArdle Disease …………………………………………………………………………………………..30 Chapter 9 Type VI Glycogen Storage Disease (abbreviated GSD VI) and Type IX Glycogen Storage Disease (abbreviated GSD IX …………………………………………………………………………….33 Chapter 10 Type VII Glycogen Storage Disease (abbreviated GSD VII) ……………………………36 Chapter 11 Type 0 Glycogen Storage Disease (abbreviated GSD 0) …………………………………38 Chapter 12 Newer Glycogen Storage Diseases ……………………………………………………………….40 Chapter 13 Parent, Family and Patient Involvement ………………………………………………………42 Chapter 14 Questions and Answers ………………………………………………………………………………44 Chapter 15 Where to Get Information …………………………………………………………………………...48 Chapter 16 Glossary of Terms Related to Glycogen Storage Disease ……………………………….49 2 AGSD’s “Glycogen Storage Diseases: A Patient-Parent Handbook” Chapter 1 The Biochemistry of Glycogen Storage Disease The underlying problem in all of the glycogen storage diseases is the use and storage of glycogen. Glycogen is a complex material composed of glucose molecules linked together. HOW THE BODY STORES GLUCOSE AS GLYCOGEN Glucose is a basic sugar (see Figure 1). It is an important source of energy for the body. and is the main transport form of energy in the blood stream. The body usually keeps the level of glucose in the blood within a narrow range of concentrations: 60-100 units (mg per deciliters). -

Glycogen Metabolism in Humans☆,☆☆

BBA Clinical 5 (2016) 85–100 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect BBA Clinical journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/bbaclin Glycogen metabolism in humans☆,☆☆ María M. Adeva-Andany ⁎, Manuel González-Lucán, Cristóbal Donapetry-García, Carlos Fernández-Fernández, Eva Ameneiros-Rodríguez Nephrology Division, Hospital General Juan Cardona, c/ Pardo Bazán s/n, 15406 Ferrol, Spain article info abstract Article history: In the human body, glycogen is a branched polymer of glucose stored mainly in the liver and the skeletal muscle Received 25 November 2015 that supplies glucose to the blood stream during fasting periods and to the muscle cells during muscle contrac- Received in revised form 10 February 2016 tion. Glycogen has been identified in other tissues such as brain, heart, kidney, adipose tissue, and erythrocytes, Accepted 16 February 2016 but glycogen function in these tissues is mostly unknown. Glycogen synthesis requires a series of reactions that Available online 27 February 2016 include glucose entrance into the cell through transporters, phosphorylation of glucose to glucose 6-phosphate, isomerization to glucose 1-phosphate, and formation of uridine 5ʹ-diphosphate-glucose, which is the direct glu- Keywords: Glucose cose donor for glycogen synthesis. Glycogenin catalyzes the formation of a short glucose polymer that is extended Glucokinase by the action of glycogen synthase. Glycogen branching enzyme introduces branch points in the glycogen particle Phosphoglucomutases at even intervals. Laforin and malin are proteins involved in glycogen assembly but their specificfunctionremains Glycogen synthase elusive in humans. Glycogen is accumulated in the liver primarily during the postprandial period and in the skel- Glycogen phosphorylase etal muscle predominantly after exercise. -

A Genetic Investigation of the Muscle and Neuronal Channelopathies: from Sanger to Next – Generation Sequencing

A Genetic Investigation of the Muscle and Neuronal Channelopathies: From Sanger to Next – Generation Sequencing Alice Gardiner MRC Centre for Neuromuscular Diseases and UCL Institute of Neurology Supervised by Professor Henry Houlden and Professor Mike Hanna 1 Declaration I, Alice Gardiner, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signature A~~~ . Date ~.'t..J.q~ l.?,.q.l.~ . 2 Abstract The neurological channelopathies are a group of hereditary, episodic and frequently debilitating diseases often caused by dysfunction of voltage-gated ion channels. This thesis reports genetic studies of carefully clinically characterised patient cohorts with different episodic neurological and neuromuscular disorders including paroxysmal dyskinesias, episodic ataxia, periodic paralysis and episodic rhabdomyolysis. Genetic and clinical heterogeneity has in the past, using traditional Sanger sequencing methods, made genetic diagnosis difficult and time consuming. This has led to many patients and families being undiagnosed. Here, different sequencing technologies were employed to define the genetic architecture in the paroxysmal disorders. Initially, Sanger sequencing was employed to screen the three known paroxysmal dyskinesia genes in a large cohort of paroxysmal movement disorder patients and smaller mixed episodic phenotype cohort. A genetic diagnosis was achieved in 39% and 13% of the cohorts respectively, and the genetic and phenotypic overlap was highlighted. Subsequently, next-generation sequencing panels were developed, for the first time in our laboratory. Small custom-designed amplicon-based panels were used for the skeletal muscle and neuronal channelopathies. They offered considerable clinical and practical benefit over traditional Sanger sequencing and revealed further phenotypic overlap, however there were still problems to overcome with incomplete coverage. -

Glycogen Metabolism and Glycogen Storage Disorders

474 Review Article on Inborn Errors of Metabolism Page 1 of 18 Glycogen metabolism and glycogen storage disorders Shibani Kanungo1, Kimberly Wells1, Taylor Tribett1, Areeg El-Gharbawy2 1Department of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo, MI, USA; 2Department of Pediatrics, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, PA, USA Contributions: (I) Conception and design: S Kanungo; (II) Administrative support: S Kanungo; (III) Provision of study materials or patients: S Kanungo; (IV) Collection and assembly of data: All authors; (V) Data analysis and interpretation: S Kanungo; (VI) Manuscript writing: All authors; (VII) Final approval of manuscript: All authors. Correspondence to: Shibani Kanungo, MD, MPH. Department of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker MD School of Medicine, 1000 Oakland Drive, Kalamazoo MI 49008, USA. Email: [email protected]. Abstract: Glucose is the main energy fuel for the human brain. Maintenance of glucose homeostasis is therefore, crucial to meet cellular energy demands in both - normal physiological states and during stress or increased demands. Glucose is stored as glycogen primarily in the liver and skeletal muscle with a small amount stored in the brain. Liver glycogen primarily maintains blood glucose levels, while skeletal muscle glycogen is utilized during high-intensity exertion, and brain glycogen is an emergency cerebral energy source. Glycogen and glucose transform into one another through glycogen synthesis and degradation pathways. Thus, enzymatic defects along these pathways are associated with altered glucose metabolism and breakdown leading to hypoglycemia ± hepatomegaly and or liver disease in hepatic forms of glycogen storage disorder (GSD) and skeletal ± cardiac myopathy, depending on the site of the enzyme defects. -

Metabolic Disorders (Children)

E06/S/b 2013/14 NHS STANDARD CONTRACT METABOLIC DISORDERS (CHILDREN) PARTICULARS, SCHEDULE 2 – THE SERVICES, A – SERVICE SPECIFICATION Service Specification E06/S/b No. Service Metabolic Disorders (Children) Commissioner Lead Provider Lead Period 12 months Date of Review 1. Population Needs 1.1 National/local context and evidence base National Context Inherited Metabolic Disorders (IMDs) cover a group of over 600 individual conditions, each caused by defective activity in a single enzyme or transport protein. Although individually metabolic conditions are rare, the incidence being less than 1.5 per 10,000 births, collectively they are a considerable cause of morbidity and mortality. The diverse range of conditions varies widely in presentation and management according to which body systems are affected. For some patients presentation may be in the newborn period, whereas for others with the same disease (but a different genetic mutation) onset may be later, including adulthood. Without early identification and/or introduction of specialist diet or drug treatments, patients face severe disruption of metabolic processes in the body such as energy production, manufacture of breakdown of proteins, and management and storage of fats and fatty acids. The result is that patients have either a deficiency of products essential to health or an accumulation of unwanted or toxic products. Without treatment many conditions can lead to severe learning or physical disability and death at an early age. The rarity and complex nature of IMD requires an integrated specialised clinical and laboratory service to provide satisfactory diagnosis and management. This is in keeping with the recommendation of the 1 NHS England E06/S/b © NHS Commissioning Board, 2013 The NHS Commissioning Board is now known as NHS England Department of Health’s UK Plan for Rare Disorders consultation to use specialist centres Approximately 10-12,000 paediatric and adult patients attend UK specialist IMD centres, but a significant number of patients remain undiagnosed or are ‘lost to follow-up’. -

Mendeliome Panel Versie V3 (4362 Genen) Centrum Voor Medische Genetica Gent

H9.1-OP2-B24: Genpanel Mendeliome, in voege op 15/09/2020 Mendeliome panel versie V3 (4362 genen) Centrum voor Medische Genetica Gent Associated phenotype, OMIM phenotype ID, phenotype Gene OMIM gene ID mapping key and inheritance pattern {Alzheimer disease, susceptibility to}, 104300 (3), Autosomal A2M 103950 dominant A2ML1 610627 {Otitis media, susceptibility to}, 166760 (3), Autosomal dominant [Blood group, P1Pk system, p phenotype], 111400 (3); NOR A4GALT 607922 polyagglutination syndrome, 111400 (3); [Blood group, P1Pk system, P(2) phenotype], 111400 (3) Achalasia-addisonianism-alacrimia syndrome, 231550 (3), AAAS 605378 Autosomal recessive Keratoderma, palmoplantar, punctate type IA, 148600 (3), AAGAB 614888 Autosomal dominant Epileptic encephalopathy, early infantile, 29, 616339 (3), AARS1 601065 Autosomal recessive; Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, axonal, type (AARS) 2N, 613287 (3), Autosomal dominant Combined oxidative phosphorylation deficiency 8, 614096 (3), AARS2 612035 Autosomal recessive; Leukoencephalopathy, progressive, with ovarian failure, 615889 (3), Autosomal recessive AASS 605113 Hyperlysinemia, 238700 (3), Autosomal recessive ABAT 137150 GABA-transaminase deficiency, 613163 (3), Autosomal recessive HDL deficiency, familial, 1, 604091 (3); Tangier disease, 205400 ABCA1 600046 (3), Autosomal recessive Ichthyosis, congenital, autosomal recessive 4B (harlequin), ABCA12 607800 242500 (3), Autosomal recessive; Ichthyosis, congenital, autosomal recessive 4A, 601277 (3), Autosomal recessive Intellectual developmental disorder