The Lexeme in Descriptive and Theoretical Morphology, 3–18

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Linguistic Dimension of Terminology

1st Athens International Conference on Translation and Interpretation Translation: Between Art and Social Science, 13 -14 October 2006 THE LINGUISTIC DIMENSION OF TERMINOLOGY: PRINCIPLES AND METHODS OF TERM FORMATION Kostas Valeontis Elena Mantzari Physicist-Electronic Engineer, President of ΕLΕΤΟ1, Linguist-Researcher, Deputy Secretary General of ΕLΕΤΟ Abstract Terminology has a twofold meaning: 1. it is the discipline concerned with the principles and methods governing the study of concepts and their designations (terms, names, symbols) in any subject field, and the job of collecting, processing, and managing relevant data, and 2. the set of terms belonging to the special language of an individual subject field. In its study of concepts and their representations in special languages, terminology is multidisciplinary, since it borrows its fundamental tools and concepts from a number of disciplines (e.g. logic, ontology, linguistics, information science and other specific fields) and adapts them appropriately in order to cover particularities in its own area. The interdisciplinarity of terminology results from the multifaceted character of terminological units, as linguistic items (linguistics), as conceptual elements (logic, ontology, cognitive sciences) and as vehicles of communication in both scientific and generic language contexts. Accordingly, the theory of terminology can be identified as having three different dimensions: the cognitive, the linguistic, and the communicative dimension (Sager: 1990). The linguistic dimension of the theory of terminology can be detected mainly in the linguistic mechanisms that set the patterns for term formation and term forms. In this paper, we will focus on the presentation of general linguistic principles concerning term formation, during primary naming of an original concept in a source language and secondary term formation in a target language. -

File: Terminology.Pdf

Lowe I 2009, www.scientificlanguage.com/esp/terminology.pdf 1 A question of terminology ______________________________________________________________ This essay is copyright under the creative commons Attribution - Noncommercial - Share Alike 3.0 Unported licence. You are encouraged to share and copy this essay free of charge. See for details: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ A question of terminology Updated 24 November 2009 24 November 2009 A framework for analysing sub/semi-technical words is presented which reconciles the two senses of these terms. Additional practical ideas for teaching them are provided. 0. Introduction The terminology for describing the language of science is in a state of confusion. There are several words, with differing definitions. There is even confusion over exactly what should be defined and labelled. In other words, there is a problem of classification. This paper attempts to sort out some of the confusion. 1. Differing understandings of what is meant by “general” English and “specialised” English (see also www.scientificlanguage.com/esp/audience.pdf ) Table to show the different senses of ‘general’ and ‘specialised’ Popular senses Technical senses 1. a wide range of general 2. Basic English, of all interest topics of general kinds, from pronunciation, “general” English knowledge, such as sport, through vocabulary, to hobbies etc discourse patterns such as Suggested term: those used in a newspaper. general topics English Suggested terms: foundational English basic English 3. a wide range of topics 4. Advanced English, the within the speciality of the fine points, and the “specialised” English student. vocabulary and discourse Suggested term: patterns specific to the specialised topics English discipline. -

Facilitating Terminology Translation with Target Lemma Annotations

Facilitating Terminology Translation with Target Lemma Annotations Toms Bergmanisyz and Marcis¯ Pinnisyz yTilde / Vien¯ıbas gatve 75A, Riga, Latvia zFaculty of Computing, University of Latvia / Rain¸a bulv. 19, Riga, Latvia [email protected] Abstract has assumed that the correct morphological forms are apriori known (Hokamp and Liu, 2017; Post Most of the recent work on terminology in- and Vilar, 2018; Hasler et al., 2018; Dinu et al., tegration in machine translation has assumed 2019; Song et al., 2020; Susanto et al., 2020; Dou- that terminology translations are given already gal and Lonsdale, 2020). Thus previous work has inflected in forms that are suitable for the tar- get language sentence. In day-to-day work of approached terminology translation predominantly professional translators, however, it is seldom as a problem of making sure that the decoder’s the case as translators work with bilingual glos- output contains lexically and morphologically pre- saries where terms are given in their dictionary specified target language terms. While useful in forms; finding the right target language form some cases and some languages, such approaches is part of the translation process. We argue come short of addressing terminology translation that the requirement for apriori specified tar- into morphologically complex languages where get language forms is unrealistic and impedes the practical applicability of previous work. In each word can have many morphological surface this work, we propose to train machine trans- forms. lation systems using a source-side data aug- For terminology translation to be viable for trans- mentation method1 that annotates randomly se- lation into morphologically complex languages, lected source language words with their tar- terminology constraints have to be soft. -

Terminology, Phraseology, and Lexicography 1. Introduction Sinclair

Terminology, Phraseology, and Lexicography1 Patrick Hanks Institute of Formal and Applied Linguistics, Charles University in Prague This paper explores two aspects of word use and word meaning in terms of Sinclair's (1991, 1998) distinction between the open-choice principle (or terminological tendency) and the idiom principle (or phraseological tendency). Technical terms such as strobilation are rare, highly domain-specific, and of little phraseological interest, although the texts in which such word occur do tend to contain interesting clusters of domain-specific terminology. At the other extreme, it is impossible to know the meaning of ordinary common words such as the verb blow without knowing the phraseological context in which the word is used. Many words have both a terminological tendency and a phraseological tendency. In some cases the two tendencies are in harmony; in other cases there is tension between them. The relationship between these two tendencies is investigated, using examples from the British National Corpus. 1. Introduction Sinclair (1991) makes a distinction between two aspects of meaning in texts, which he calls the open-choice principle and the idiom principle. In this paper, I will try to show why it is of great importance, not only for understanding meaning in text, but also for lexicography, to try to take account of both principles even-handedly and assess the balance between them when analyzing the meaning and use of a word. The open-choice principle (alternatively called the terminological tendency) is: a way of seeing language as the result of a very large number of complex choices. At each point where a unit is complete (a word or a phrase or a clause), a large range of choices opens up and the only restraint is grammaticalness. -

The Interaction Between Terminology and Translation Or Where Terminology and Translation Meet

trans-kom ISSN 1867-4844 http://www.trans-kom.eu trans-kom ist eine wissenschaftliche Zeitschrift für Translation und Fachkommunikation. trans-kom 8 [2] (2015): 347-381 Seite 347 Marcel Thelen The Interaction between Terminology and Translation Or Where Terminology and Translation Meet Abstract In this article Terminology and Translation are compared to one another on a number of points of comparison. On the basis of the results, the cooperation/interaction between Terminology and Translation are discussed. The contribution of Terminology to Translation is obvious, but that of Translation to Terminology is less evident, yet it does exist. This article is based on a paper that I gave at the 2013 EST congress.1 1 Introduction Initially, Terminology claimed to be an independent discipline (cf. Traditional Terminology: Felber 1984: 31). This claim was later disputed by e.g. Sager (1990: 1), Temmerman (2000: 2). In fact, Terminology has gradually become rather an interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary discipline. It has been linked to a range of (sub)disciplines, from Lexicology, Semantics, Cognitive Linguistics, Sociolinguistics, Communication, to Philo- sophy and Language Planning. The basis for the above claims is the comparison of Terminology with the various disciplines in search for similarities supporting and/or dissimilarities rejecting the claim of Terminology that it is an independent discipline. In this article, I will compare Terminology with Translation, not in order to draw any conclusions about the status of Terminology, viz. whether it is a discipline and whether it is an independent discipline, but in order to find where and how Terminology and Translation cooperate and interact in the actual practice of a professional translator. -

The Role of Terminology Work in Current Translation Practice

The Role of Terminology Work in Current Translation Practice Universitat Heidelberg M. Albl, S. Braun, K. Kohn, H. Mikasa Marz 1993 European Strategic Programme for Research and Development in Information Technology ESPRIT Project No. 2315: TWB II Translator's Workbench The Role of Terminology Work in Current Translation Practice Workpackage 5.3, Tl "User Orientation" Universitat Heidelberg lnstitut fiir Dbersetzen und Dolmetschen Michaela Albl, Sabine Braun, Kurt Kohn, Hans Mikasa March 1993 Table of Contents Preface.............................................................................................................................................. 1 1 Introduction to the working environments of translators ............................................... 3 1.1 Freelance translators ................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Agency translators ....................................................................................................... .4 1.3 In-house translators in industry .................................................................................. 5 1.4 In-house translators in supranational institutions ................................................... 6 2 General description of translation practice ...................................................................... 8 2.1 Organization .................................................................................................................. 8 2.1.1 Personnel structures ........................................................................................ -

Terminology Management in a Nutshell

Terminology Management in a Nutshell Trisha Kovacic-Young Nicoleta Klimek Young Translations LLC What we will discuss • Why bother with termbases? • Term extraction vs. manual labor and quantity vs. quality • How to store all those great terms you found • How to involve your client in the process • How to leverage your terms • How to grow your termbase on the fly, add “forbidden terms” and use QA checks to spot inconsistent translation. Why bother with termbases? • Inconsistencies confuse the reader and can make your translation look “sloppy” • Save time – translate faster! • It shows your client you are reliable and precise, and that you care about his text Tip for Attach the termbases to your memoQ server, maybe your PMs: translators will add to them! Teach them how to do it. A good writer… Term extraction vs. manual labor – Automatic term extraction in memoQ Example of irrelevant term Final steps Term extraction vs. manual labor – The old fashioned way also has its merits – What are good terms? • Words that have many different possible meanings but we choose one for our client and should stick with it. • Words you had to research. • Words that are hard to type. Tip for PMs: • ANYTHING your client has mentioned to you. Choosing good terms Prof. Dr. Carsten Agert ist Leiter des EWE-Forschungszentrums Prof. Carsten Agert is the Director of the EWE Research Centre NEXT ENERGY. Das Institut wird seit dem Jahr 2008 unter dem NEXT ENERGY. The institute has operated under the auspices of Dach des gemeinnützigen Vereins „EWE-Forschungszentrum für the non-profit association “EWE Forschungszentrum für Energietechnologie e. -

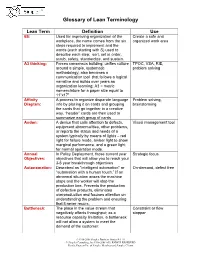

Glossary of Lean Terminology

Glossary of Lean Terminology Lean Term Definition Use 6S: Used for improving organization of the Create a safe and workplace, the name comes from the six organized work area steps required to implement and the words (each starting with S) used to describe each step: sort, set in order, scrub, safety, standardize, and sustain. A3 thinking: Forces consensus building; unifies culture TPOC, VSA, RIE, around a simple, systematic problem solving methodology; also becomes a communication tool that follows a logical narrative and builds over years as organization learning; A3 = metric nomenclature for a paper size equal to 11”x17” Affinity A process to organize disparate language Problem solving, Diagram: info by placing it on cards and grouping brainstorming the cards that go together in a creative way. “header” cards are then used to summarize each group of cards Andon: A device that calls attention to defects, Visual management tool equipment abnormalities, other problems, or reports the status and needs of a system typically by means of lights – red light for failure mode, amber light to show marginal performance, and a green light for normal operation mode. Annual In Policy Deployment, those current year Strategic focus Objectives: objectives that will allow you to reach your 3-5 year breakthrough objectives Autonomation: Described as "intelligent automation" or On-demand, defect free "automation with a human touch.” If an abnormal situation arises the machine stops and the worker will stop the production line. Prevents the production of defective products, eliminates overproduction and focuses attention on understanding the problem and ensuring that it never recurs. -

Ontology for Information Systems (O4IS) Design Methodology Conceptualizing, Designing and Representing Domain Ontologies

Ontology for Information Systems (O4IS) Design Methodology Conceptualizing, Designing and Representing Domain Ontologies Vandana Kabilan October 2007. A Dissertation submitted to The Royal Institute of Technology in partial fullfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Technology . The Royal Institute of Technology School of Information and Communication Technology Department of Computer and Systems Sciences IV DSV Report Series No. 07–013 ISBN 978–91–7178–752–1 ISSN 1101–8526 ISRN SU–KTH/DSV/R– –07/13– –SE V All knowledge that the world has ever received comes from the mind; the infinite library of the universe is in our own mind. – Swami Vivekananda. (1863 – 1902) Indian spiritual philosopher. The whole of science is nothing more than a refinement of everyday thinking. – Albert Einstein (1879 – 1955) German-Swiss-U.S. scientist. Science is a mechanism, a way of trying to improve your knowledge of na- ture. It’s a system for testing your thoughts against the universe, and seeing whether they match. – Isaac Asimov. (1920 – 1992) Russian-U.S. science-fiction author. VII Dedicated to the three KAs of my life: Kabilan, Rithika and Kavin. IX Abstract. Globalization has opened new frontiers for business enterprises and human com- munication. There is an information explosion that necessitates huge amounts of informa- tion to be speedily processed and acted upon. Information Systems aim to facilitate human decision-making by retrieving context-sensitive information, making implicit knowledge ex- plicit and to reuse the knowledge that has already been discovered. A possible answer to meet these goals is the use of Ontology. -

Onlit: an Ontology for Linguistic Terminology

OnLiT: An Ontology for Linguistic Terminology Bettina Klimek1, John P. McCrae2, Christian Lehmann3, Christian Chiarcos4, and Sebastian Hellmann1 1 InfAI, University of Leipzig, klimek,[email protected], WWW home page: aksw.org/Groups/KILT 2 Insight Centre for Data Analytics, National University of Ireland Galway, [email protected], WWW home page: https://www.insight-centre.org 3 [email protected], WWW home page: http://www.christianlehmann.eu 4 Applied Computational Linguistics, Goethe-University Frankfurt, Germany, [email protected], WWW home page: http://acoli.informatik.uni-frankfurt.de Abstract. Understanding the differences underlying the scope, usage and content of language data requires the provision of a clarifying termi- nological basis which is integrated in the metadata describing a partic- ular language resource. While terminological resources such as the SIL Glossary of Linguistic Terms, ISOcat or the GOLD ontology provide a considerable amount of linguistic terms, their practical usage is limited to a look up of a defined term whose relation to other terms is unspecified or insufficient. Therefore, in this paper we propose an ontology for linguistic terminology, called OnLiT. It is a data model which can be used to rep- resent linguistic terms and concepts in a semantically interrelated data structure and, thus, overcomes prevalent isolating definition-based term descriptions. OnLiT is based on the LiDo Glossary of Linguistic Terms and enables the creation of RDF datasets, that represent linguistic terms and their meanings within the whole or a subdomain of linguistics. Keywords: linguistic terminology, linguistic linked data, LiDo database 1 Introduction The research field of language data has evolved to encompass a multitude of inter- disciplinary scientific areas that are all more or less closely bound to the central studies of linguistics. -

Cross-Lingual Terminology Extraction for Translation Quality Estimation⋆

Cross-lingual Terminology Extraction for Translation Quality Estimation? Yu Yuany ∗, Yuze Gaoz, Yue Zhangz, Serge Sharoff∗ y School of Languages & Cultures, Nanjing University of Information Science & Technology, 210044, China z Information Systems Technology and Design, Singapore University of Technology and Design, 487372 ∗ Centre for Translation Studies, University of Leeds, LS2 9JT, United Kingdom [email protected], fyuze gao, yue [email protected] [email protected] Abstract We explore ways of identifying terms from monolingual texts and integrate them into investigating the contribution of terminology to translation quality.The researchers proposed a supervised learning method using common statistical measures for termhood and unithood as features to train classifiers for identifying terms in cross-domain and cross-language settings. On its basis, sequences of words from source texts (STs) and target texts (TTs) are aligned naively through a fuzzy matching mechanism for identifying the correctly translated term equivalents in student translations. Correlation analyses further show that normalized term occurrences in translations have weak linear relationship with translation quality in term of usefulness/transfer, terminology/style, idiomatic writing and target mechanics and near- and above-strong relationship with the overall translation quality. This method has demonstrated some reliability in automatically identifying terms in human translations. However, drawbacks in handling low frequency terms and term variations shall be dealt in the future. Keywords: Bilingual terminology, translation quality, supervised learning, correlation analysis 1. Introduction enue. Therefore, speed and quality is what localization ser- Terminology helps translators organize their domain vices users are looking for (Warburton, 2013).They would knowledge, and provides them means (usually terms in var- expect that all the terms are translated correctly and consis- ious lexical units) to express subject knowledge adequately. -

Nomenclature and Terminology Smart P., Maisonneuve H

Smart P., Maisonneuve H. and Polderman A. (eds) Science Editors’ Handbook European Association of Science Editors. www.ease.org.uk Section 2: Nomenclature and terminology Smart P., Maisonneuve H. and Polderman A. (eds) Science Editors’ Handbook European Association of Science Editors. www.ease.org.uk 2.1: Nomenclature and typography in chemistry and pharmacy Arjan K.S. Polderman Pharmaceutisch Weekblad, PO Box 30460, 2500 GL The Hague, Netherlands; [email protected] Chemical nomenclature rules for editorial practice can be found in Scientific Style Correct nomenclature in chemistry needs more guidance and Format.2 The IUPAC International Chemical Identifier than this chapter can provide. Names for chemical (InChI; see chapter 14 of1), intended for use by computers, compounds are generally intended to reflect molecular has gained widespread acceptance as a means of specifying structure, and for complex molecules can often be long and linking designations of chemical compounds in the and cumbersome. To derive such names correctly from chemistry literature. internationally agreed nomenclature rules needs a degree of expertise normally accessible only to the specialist chemical Names and formulas for elements and inorganic editor. The number of guidelines and standards for both molecules names of molecules and general chemical terminology There are two major distinctions in chemical nomenclature: is overwhelming, but a few general guidelines will be names versus formulas, and organic versus inorganic presented in this chapter. Some guidelines may appear chemistry. to be mutually conflicting (in most of such cases it has Molecular formulas are based on symbols for over 100 been agreed which guideline overrules the others); many chemical elements; these symbols consist of one or two guidelines have exceptions; and most of them need careful letters, the first (or only one) being an upper case, the second interpretation.