Cutaneous Amebiasis in Pediatrics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Index Vol. 12-15

353 INDEX VOL. 12-15 Die Stichworte des Sachregisters sind in der jeweiligen Sprache der einzelnen Beitrage aufgefiihrt. Les termes repris dans la Table des matieres sont donnes selon la langue dans laquelle l'ouvrage est ecrit. The references of the Subject Index are given in the language of the respective contribution. 14 AAG (Alpha-acid glycoprotein) 120 14 Adenosine 108 12 Abortion 151 12 Adenosine-phosphate 311 13 Abscisin 12, 46, 66 13 Adenosine-5'-phosphosulfate 148 14 Absorbierbarkeit 317 13 Adenosine triphosphate 358 14 Absorption 309, 350 15 S-Adenosylmethionine 261 13 Absorption of drugs 139 13 Adipaenin (Spasmolytin) 318 14 - 15 12 Adrenal atrophy 96 14 Absorptionsgeschwindigkeit 300, 306 14 - 163, 164 14 Absorptionsquote 324 13 Adrenal gland 362 14 ACAI (Anticorticocatabolic activity in 12 Adrenalin(e) 319 dex) 145 14 - 209, 210 12 Acalo 197 15 - 161 13 Aceclidine (3-Acetoxyquinuclidine) 307, 13 {i-Adrenergic blockers 119 308, 310, 311, 330, 332 13 Adrenergic-blocking activity 56 13 Acedapsone 193,195,197 14 O(-Adrenergic blocking drugs 36, 37, 43 13 Aceperone (Acetabutone) 121 14 {i-Adrenergic blocking drugs 38 12 Acepromazin (Plegizil) 200 14 Adrenergic drugs 90 15 Acetanilid 156 12 Adrenocorticosteroids 14, 30 15 Acetazolamide 219 12 Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) 13 Acetoacetyl-coenzyme A 258 16,30,155 12 Acetohexamide 16 14 - 149,153,163,165,167,171 15 1-Acetoxy-8-aminooctahydroindolizin 15 Adrenocorticotropin (ACTH) 216 (Slaframin) 168 14 Adrenosterone 153 13 4-Acetoxy-1-azabicyclo(3, 2, 2)-nonane 12 Adreson 252 -

)&F1y3x PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX to THE

)&f1y3X PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE HARMONIZED TARIFF SCHEDULE )&f1y3X PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE TARIFF SCHEDULE 3 Table 1. This table enumerates products described by International Non-proprietary Names (INN) which shall be entered free of duty under general note 13 to the tariff schedule. The Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) registry numbers also set forth in this table are included to assist in the identification of the products concerned. For purposes of the tariff schedule, any references to a product enumerated in this table includes such product by whatever name known. Product CAS No. Product CAS No. ABAMECTIN 65195-55-3 ACTODIGIN 36983-69-4 ABANOQUIL 90402-40-7 ADAFENOXATE 82168-26-1 ABCIXIMAB 143653-53-6 ADAMEXINE 54785-02-3 ABECARNIL 111841-85-1 ADAPALENE 106685-40-9 ABITESARTAN 137882-98-5 ADAPROLOL 101479-70-3 ABLUKAST 96566-25-5 ADATANSERIN 127266-56-2 ABUNIDAZOLE 91017-58-2 ADEFOVIR 106941-25-7 ACADESINE 2627-69-2 ADELMIDROL 1675-66-7 ACAMPROSATE 77337-76-9 ADEMETIONINE 17176-17-9 ACAPRAZINE 55485-20-6 ADENOSINE PHOSPHATE 61-19-8 ACARBOSE 56180-94-0 ADIBENDAN 100510-33-6 ACEBROCHOL 514-50-1 ADICILLIN 525-94-0 ACEBURIC ACID 26976-72-7 ADIMOLOL 78459-19-5 ACEBUTOLOL 37517-30-9 ADINAZOLAM 37115-32-5 ACECAINIDE 32795-44-1 ADIPHENINE 64-95-9 ACECARBROMAL 77-66-7 ADIPIODONE 606-17-7 ACECLIDINE 827-61-2 ADITEREN 56066-19-4 ACECLOFENAC 89796-99-6 ADITOPRIM 56066-63-8 ACEDAPSONE 77-46-3 ADOSOPINE 88124-26-9 ACEDIASULFONE SODIUM 127-60-6 ADOZELESIN 110314-48-2 ACEDOBEN 556-08-1 ADRAFINIL 63547-13-7 ACEFLURANOL 80595-73-9 ADRENALONE -

A Screening-Based Approach to Circumvent Tumor Microenvironment

JBXXXX10.1177/1087057113501081Journal of Biomolecular ScreeningSingh et al. 501081research-article2013 Original Research Journal of Biomolecular Screening 2014, Vol 19(1) 158 –167 A Screening-Based Approach to © 2013 Society for Laboratory Automation and Screening DOI: 10.1177/1087057113501081 Circumvent Tumor Microenvironment- jbx.sagepub.com Driven Intrinsic Resistance to BCR-ABL+ Inhibitors in Ph+ Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Harpreet Singh1,2, Anang A. Shelat3, Amandeep Singh4, Nidal Boulos1, Richard T. Williams1,2*, and R. Kiplin Guy2,3 Abstract Signaling by the BCR-ABL fusion kinase drives Philadelphia chromosome–positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph+ ALL) and chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML). Despite their clinical activity in many patients with CML, the BCR-ABL kinase inhibitors (BCR-ABL-KIs) imatinib, dasatinib, and nilotinib provide only transient leukemia reduction in patients with Ph+ ALL. While host-derived growth factors in the leukemia microenvironment have been invoked to explain this drug resistance, their relative contribution remains uncertain. Using genetically defined murine Ph+ ALL cells, we identified interleukin 7 (IL-7) as the dominant host factor that attenuates response to BCR-ABL-KIs. To identify potential combination drugs that could overcome this IL-7–dependent BCR-ABL-KI–resistant phenotype, we screened a small-molecule library including Food and Drug Administration–approved drugs. Among the validated hits, the well-tolerated antimalarial drug dihydroartemisinin (DHA) displayed potent activity in vitro and modest in vivo monotherapy activity against engineered murine BCR-ABL-KI–resistant Ph+ ALL. Strikingly, cotreatment with DHA and dasatinib in vivo strongly reduced primary leukemia burden and improved long-term survival in a murine model that faithfully captures the BCR-ABL-KI–resistant phenotype of human Ph+ ALL. -

The Alkaloid Emetine As a Promising Agent for the Induction and Enhancement of Drug-Induced Apoptosis in Leukemia Cells

737-744 26/7/07 08:26 Page 737 ONCOLOGY REPORTS 18: 737-744, 2007 737 The alkaloid emetine as a promising agent for the induction and enhancement of drug-induced apoptosis in leukemia cells MAREN MÖLLER1, KERSTIN HERZER3, TILL WENGER2,4, INGRID HERR2 and MICHAEL WINK1 1Institute of Pharmacy and Molecular Biotechnology, University of Heidelberg, Im Neuenheimer Feld 364; 2Molecular OncoSurgery, Department of Surgery, University and German Cancer Research Center, Im Neuenheimer Feld 365, 69120 Heidelberg; 31st Department of Internal Medicine, University of Mainz, Langenbeckstrasse 1, 55131 Mainz, Germany; 4Centre d'Immunologie de Marseille-Luminy, Marseille, France Received January 8, 2007; Accepted February 20, 2007 Abstract. Emetine, a natural alkaloid from Psychotria caused mainly by two isoquinoline alkaloids, emetine and ipecacuanha, has been used in phytomedicine to induce cephaeline, having identical effects regarding the irritation of vomiting, and to treat cough and severe amoebiasis. Certain the respiratory tract (1). Nowadays, ipecac syrup is no longer data suggest the induction of apoptosis by emetine in recommended for the routine use in the management of leukemia cells. Therefore, we examined the suitability of poisoned patients (2) and recently a guideline on the use of emetine for the sensitisation of leukemia cells to apoptosis ipecac syrup was published, stating that ‘the circumstances in induced by cisplatin. In response to emetine, we found a which ipecac-induced emesis is the appropriate or desired strong reduction in viability, an induction of apoptosis and method of gastric decontamination are rare’ (3). Moreover, at caspase activity comparable to the cytotoxic effect of present there is a demand to remove ipecac from the over- cisplatin. -

![Ehealth DSI [Ehdsi V2.2.2-OR] Ehealth DSI – Master Value Set](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8870/ehealth-dsi-ehdsi-v2-2-2-or-ehealth-dsi-master-value-set-1028870.webp)

Ehealth DSI [Ehdsi V2.2.2-OR] Ehealth DSI – Master Value Set

MTC eHealth DSI [eHDSI v2.2.2-OR] eHealth DSI – Master Value Set Catalogue Responsible : eHDSI Solution Provider PublishDate : Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 © eHealth DSI eHDSI Solution Provider v2.2.2-OR Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 Page 1 of 490 MTC Table of Contents epSOSActiveIngredient 4 epSOSAdministrativeGender 148 epSOSAdverseEventType 149 epSOSAllergenNoDrugs 150 epSOSBloodGroup 155 epSOSBloodPressure 156 epSOSCodeNoMedication 157 epSOSCodeProb 158 epSOSConfidentiality 159 epSOSCountry 160 epSOSDisplayLabel 167 epSOSDocumentCode 170 epSOSDoseForm 171 epSOSHealthcareProfessionalRoles 184 epSOSIllnessesandDisorders 186 epSOSLanguage 448 epSOSMedicalDevices 458 epSOSNullFavor 461 epSOSPackage 462 © eHealth DSI eHDSI Solution Provider v2.2.2-OR Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 Page 2 of 490 MTC epSOSPersonalRelationship 464 epSOSPregnancyInformation 466 epSOSProcedures 467 epSOSReactionAllergy 470 epSOSResolutionOutcome 472 epSOSRoleClass 473 epSOSRouteofAdministration 474 epSOSSections 477 epSOSSeverity 478 epSOSSocialHistory 479 epSOSStatusCode 480 epSOSSubstitutionCode 481 epSOSTelecomAddress 482 epSOSTimingEvent 483 epSOSUnits 484 epSOSUnknownInformation 487 epSOSVaccine 488 © eHealth DSI eHDSI Solution Provider v2.2.2-OR Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 Page 3 of 490 MTC epSOSActiveIngredient epSOSActiveIngredient Value Set ID 1.3.6.1.4.1.12559.11.10.1.3.1.42.24 TRANSLATIONS Code System ID Code System Version Concept Code Description (FSN) 2.16.840.1.113883.6.73 2017-01 A ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM 2.16.840.1.113883.6.73 2017-01 -

ED227273.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUft ED 227 273 y CE 035 300 ' TITLE APharmacy Spicialist, Militkry Curriculum Materials for Vocation47 andileChlaical Education. INSTITuTION Air Force Training Command, Sheppa* AFB, Tex.; Ohio State Univ., Columbus. Natfonal Center for Research in Vocational Education. SPONS AGENCY Office of Education (DHEW)x Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 18 Jul 75 NOTE 774p.; Some pages are marginally legible. ,PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Use Guides (For Teachers) (052), , EDRS ?RICE 14P05/PC31 Plus Postage. ` DESCRIPTORS Behavioral Objectives; Course Descriptions; A Curriculum Guides; Drug Abuse; Drug,Therapy; 4Drug Use; Learning Activities; Lesson Plans; *Pharmaceutical Education; Pharmacists; *Pharmacology; *Pharmacy; Postsecondary Education; Programed Instructional Materials; Textbooks; Workbooks IDENTIFIERS. Military CuFr.iculum Project liBSTRACT These teacher and studdnt,materials for a . postsecondary-level course in pharmacy comprise one of a numberof military-developed curriculum packages selected for adaptation to voCational instruction 'and curriculum dei7elopment in acivilian setting. The purpose stated for the 256-hour course iS totrain students in the basic technical phases of pharmacy and theminimum essential knowledge and skills necessaryior.the compounding and - dispensing of drugs, the economical operation of a pharmacy,and the proper use of drugs, chemicals, andbiological products. The course consists of three blocks of instruction. Block I contains four, lessons: pharmaceutical calculations I and laboratory,inorganic chemistry, and organic chemistry. The five lessons in Block II cover anatomy ,and physiology, introduction topharmacoloe, toxicology, drug abuse, and pharmaceutical and medicinal agents. Block III provides five lessons: phdrmaceutical calculations\I and II, techniques"of pharmaceutical compounding, pharmaceutiCal dosage for s, and compounding laboratbry. Instructormaterials include a cb se chart, lesson plans, and aplan of instruction detailing instructional,bnits, criterion objectives, lesson duration,and support materials needed. -

International Journal for Scientific Research & Development| Vol. 4, Issue 09, 2016 | ISSN (Online): 2321-0613

IJSRD - International Journal for Scientific Research & Development| Vol. 4, Issue 09, 2016 | ISSN (online): 2321-0613 Study of Percentage Tinidazole in Different Brands of Antiprotozoal Tablets Contation Tinidazole Shiv Pratap Singh Dangi1 R.N. Shukla2 P.K. Sharma3 1Msc Student 2Professor & HOD 3Associated Professor 1,2,3Department of Applied Chemistry 1,2,3Samrat Ashok Technological Institute Vidisha (M.P.) 464001 [India] Abstract— Protozoal diseases particularly malaria, leishmaniasis and changes disease, are major cause of II. MATERIALS AND METHODS mortality in various tropical and subtropical regions. Where Antiprotozoal are drugs to treat infection cause by A. Collection of Samples: unicellular organisms that destroy protozoa or inhibit their I have collected four samples of different brands of growth and the ability to reproduce. Protozoal infection antiprotozoal tablets containing Tinidazole then desigenteted transmission can be person to person by infected water or as, TZ-1, TZ-2, TZ-3 and TZ-4. food, direct contact with a parasite, a mosquito or tick. B. Chemical and Reagents: Tinidazole is the most preferred choice of drug for intestinal amoebiasis. The aim of this study is to carry out the quality Methanol, Acetone, Dichloromethane and distilled water, all test of different brands of Tinidazole Tablets I analyzed solvents and reagents used were of analytical grade. various parameters such as identification, solubility and % assay to check the quality. All the tablets compared with III. METHODS authorized standard were found within the range. A. Description Key words: Tinidazole, Anti-protozoal, Amoebiasis, The description of each sample was performed as per the IP Protozoal disease, Anti-protozoal drug volume (III) 2007[10]. -

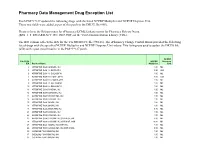

Pharmacy Data Management Drug Exception List

Pharmacy Data Management Drug Exception List Patch PSS*1*127 updated the following drugs with the listed NCPDP Multiplier and NCPDP Dispense Unit. These two fields were added as part of this patch to the DRUG file (#50). Please refer to the Release notes for ePharmacy/ECME Enhancements for Pharmacy Release Notes (BPS_1_5_EPHARMACY_RN_0907.PDF) on the VistA Documentation Library (VDL). The IEN column reflects the IEN for the VA PRODUCT file (#50.68). The ePharmacy Change Control Board provided the following list of drugs with the specified NCPDP Multiplier and NCPDP Dispense Unit values. This listing was used to update the DRUG file (#50) with a post install routine in the PSS*1*127 patch. NCPDP File 50.68 NCPDP Dispense IEN Product Name Multiplier Unit 2 ATROPINE SO4 0.4MG/ML INJ 1.00 ML 3 ATROPINE SO4 1% OINT,OPH 3.50 GM 6 ATROPINE SO4 1% SOLN,OPH 1.00 ML 7 ATROPINE SO4 0.5% OINT,OPH 3.50 GM 8 ATROPINE SO4 0.5% SOLN,OPH 1.00 ML 9 ATROPINE SO4 3% SOLN,OPH 1.00 ML 10 ATROPINE SO4 2% SOLN,OPH 1.00 ML 11 ATROPINE SO4 0.1MG/ML INJ 1.00 ML 12 ATROPINE SO4 0.05MG/ML INJ 1.00 ML 13 ATROPINE SO4 0.4MG/0.5ML INJ 1.00 ML 14 ATROPINE SO4 0.5MG/ML INJ 1.00 ML 15 ATROPINE SO4 1MG/ML INJ 1.00 ML 16 ATROPINE SO4 2MG/ML INJ 1.00 ML 18 ATROPINE SO4 2MG/0.7ML INJ 0.70 ML 21 ATROPINE SO4 0.3MG/ML INJ 1.00 ML 22 ATROPINE SO4 0.8MG/ML INJ 1.00 ML 23 ATROPINE SO4 0.1MG/ML INJ,SYRINGE,5ML 5.00 ML 24 ATROPINE SO4 0.1MG/ML INJ,SYRINGE,10ML 10.00 ML 25 ATROPINE SO4 1MG/ML INJ,AMP,1ML 1.00 ML 26 ATROPINE SO4 0.2MG/0.5ML INJ,AMP,0.5ML 0.50 ML 30 CODEINE PO4 30MG/ML -

CRUX 71Sepoct2015

VOLUME - XII ISSUE - LXXI SEP/OCT 2015 Amoebiasis, also known as amebiasis or entamobiasis, is an infection caused by any of the amoebas of the Entamoeba group. Symptoms are most common upon infection by Entamoeba histolytica. Amoebiasis can present with no, mild, or severe symptoms. Symptoms may include abdominal pain, mild diarrhoea, bloody diarrhea or severe colitis with tissue death and perforation. This last complication may cause peritonitis. People affected may develop anemia due to loss of 1 Editorial blood. Disease Invasion of the intestinal lining causes amoebic bloody diarrhea or amoebic colitis. If the parasite 2 reaches the bloodstream it can spread through the body, most frequently ending up in the liver Diagnosis where it causes amoebic liver abscesses. Liver abscesses can occur without previous diarrhea. Cysts of entamoeba can survive for up to a month in soil or for up to 45 minutes under fingernails. It 9 Trouble is important to differentiate between amoebiasis and bacterial colitis. The preferred diagnostic Shooting method it through faecal examination under microscope, but requires a skilled microscopist and may not be reliable when excluding infection. Increased white blood cell count is present in severe 10 Bouquet cases, but not in mild ones. The most accurate test is for antibodies in the blood, but it may remain positive following treatment. Prevention of amoebiasis is by separating food and water from faeces and by proper sanitation 11 Interpretation measures. There is no vaccine. There are two treatment options depending on the location of the infection. Amoebiasis in tissues is treated with either metronidazole, tinidazole, nitazoxanide, 12 Tulip News dehydroemetine or chloroquine, while luminal infection is treated with diloxanide furoate or iodoquinoline. -

POISONS LIST APPENDIX Amoebicides: Carbarsone

POISONS LIST APPENDIX Amoebicides: Carbarsone Clioquinol and other halogenated hydroxyquinoline compounds Dehydroemetine; its salts Diloxanide; its compounds Dimetridazole Emetine Ipronidazole Metronidazole Pentamidine; its salts Ronidazole Anaesthetics: Alphadolone acetate Alphaxolone Desflurane Disoprofol Enflurane Ethyl ether Etomidate; its salts Halothane Isoflurane Ketamine; its salts Local anaesthetics, the following: their salts; their homologues and analogues; their molecular compounds Amino-alcohols esterified with benzoic acid, phenylacetic acid, phenylpropionic acid, cinnamic acid or the derivatives of these acids; their salts Benzocaine Bupivacaine Butyl aminobenzoate Cinchocaine Diperodon Etidocaine Levobupivacaine Lignocaine Mepivacaine Orthocaine Oxethazaine Phenacaine Phenodianisyl Prilocaine Ropivacaine Phencyclidine; its salts Propanidid Sevoflurane Tiletamine; its salts Tribromoethanol Analeptics and Central Stimulants: Amiphenazole; its salts Amphetamine (DD) Bemegride Cathine Cathinone (DD) Dimethoxybromoamphetamine (DOB) (DD) 2, 5-Dimethoxyamphetamine (DMA) (DD) 2, 5-Dimethoxy-4-ethylamphetamine (DOET) (DD) Ethamivan N-Ethylamphetamine; its salts N-Ethyl MDA (DD) N-Hydroxy MDA (DD) Etryptamine (DD) Fencamfamine Fenetylline Lefetamine or SPA or (-)-1-dimethylamino-1, 2-diphenylethane Leptazol Lobelia, alkaloids of Meclofenoxate; its salts Methamphetamine (DD) Methcathinone (DD) 5-Methoxy-3, 4-methylenedioxyamphetamine (MMDA) (DD) Methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA) (DD) 3, 4-Methylenedioxymetamphetamine (MDMA) (DD) Methylphenidate; -

Short Reports Metronidazole in Treatment of Children with Amoebic Liver Abscess

Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/adc.48.11.911 on 1 November 1973. Downloaded from Short reports Archives of Disease in Childhood, 1973, 48, 911. Metronidazole in treatment of multiple abscesses which were not accessible by needle aspiration. All recovered but were given children with amoebic liver dehydroemetine during the postoperative period. abscess No relapses were observed during a 3-month follow-up. We have shown that metronidazole combined with dehydroemetine is an effective treatment of Discussion children with amoebic liver abscess and that the The results of this trial are similar to those former drug has advantages over chloroquine obtained in our previous study of metronidazole (Scragg and Powell, 1970). In adults, metro- combined with dehydroemetine in which 11 of 15 nidazole in the absence of other drug therapy is children were cured, 2 more required surgical extremely effective in curing amoebic liver abscess drainage, and 2 died (Scragg and Powell, 1970). and remains the best of the nitroimidazole We have indicated that age is a most important derivatives that we have investigated (Powell, 1972; factor in prognosis and that, regardless of the nature Powell and Elsdon-Dew, 1972). However, in the ofthe therapy, mortality is higher in infants and very very young we have been reluctant to abandon young children (Scragg and Powell, 1968). In the parenteral emetine preparations owing to the present study the average age of our patients was severity of the condition in this age group. Never- significantly lower than in our previous trials, hence theless, the highly satisfactory results that we have the efficacy of metronidazole alone was put to a obtained with metronidazole alone in hundreds of rigorous test. -

Drug Resistance in the Sexually Transmitted Protozoan Trichomonas Vaginalis

Cell Research (2003); 13(4):239-249 http://www.cell-research.com Drug resistance in the sexually transmitted protozoan Trichomonas vaginalis 1, 2 1 1 2 REBECCA L DUNNE , LINDA A DUNN , PETER UPCROFT , PETER J O'DONOGHUE , JACQUELINE A UPCROFT1,* 1 The Queensland Institute of Medical Research; The Australian Centre for International and TropicalHealth and Nutrition; Brisbane, Queensland 4029, Australia 2 The School of Molecular and Microbial Science, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Queensland 4072, Australia ABSTRACT Trichomoniasis is the most common, sexually transmitted infection. It is caused by the flagellated protozoan parasite Trichomonas vaginalis. Symptoms include vaginitis and infections have been associated with preterm delivery, low birth weight and increased infant mortality, as well as predisposing to HIV/AIDS and cervical cancer. Trichomoniasis has the highest prevalence and incidence of any sexually transmitted infection. The 5- nitroimidazole drugs, of which metronidazole is the most prescribed, are the only approved, effective drugs to treat trichomoniasis. Resistance against metronidazole is frequently reported and cross-resistance among the family of 5-nitroimidazole drugs is common, leaving no alternative for treatment, with some cases remaining unresolved. The mechanism of metronidazole resistance in T. vaginalis from treatment failures is not well understood, unlike resistance which is developed in the laboratory under increasing metronidazole pressure. In the latter situation, hydrogenosomal function which is involved in activation of the prodrug, metronidazole, is down-regulated. Reversion to sensitivity is incomplete after removal of drug pressure in the highly resistant parasites while clinically resistant strains, so far analysed, maintain their resistance levels in the absence of drug pressure.