XXVI Space Utopia in the 1970S of the Twentieth Century on the Basis Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Magma Magma Mp3, Flac, Wma

Magma Magma mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz / Rock Album: Magma Country: France Style: Jazz-Rock, Avantgarde, Prog Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1979 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1644 mb WMA version RAR size: 1806 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 970 Other Formats: VQF MP3 AUD DXD AA AAC MPC Tracklist Hide Credits Le Voyage Kobaïa 1-1 10:09 Written-By – Christian Vander Aïna 1-2 6:15 Written-By – Christian Vander Malaria 1-3 4:20 Written-By – Christian Vander Sohïa 1-4 7:41 Written-By – Teddy Lasry Sckxyss 1-5 2:47 Written-By – François Cahen Auraë 1-6 10:52 Written-By – Christian Vander La Decouverte De Kobaïa Thaud Zaïa 2-1 7:00 Written-By – Claude Engel Naü Ektila 2-2 12:55 Written-By – Laurent Thibault Stöah 2-3 8:08 Written-By – Christian Vander Müh 2-4 11:17 Written-By – Christian Vander Companies, etc. Distributed By – Harmonia Mundi Made By – MPO Credits Alto Saxophone, Tenor Saxophone, Flute – Richard Raux Design [Maquette] – M.-J. Petit* Drums, Vocals – Christian Vander Electric Bass, Contrabass – Francis Moze Engineer [Ingénieurs Du Son] – Claude Martelot*, Roger Roche Guitar [Guitars], Flute, Vocals – Claude Engel Piano – François Cahen Producer [Production Et Réalisation] – Laurent Thibault Soprano Saxophone, Flute [First Flute], Wind [Instruments À Vent] – Teddy Lasry Stage Manager [Régisseur] – Louis Haig Sarkissian Supervised By [Supervision De La Réalisation] – Lee Hallyday Technician [Assistant Technique] – Marcel Engel Trumpet, Percussion – Alain Charlery «Paco»* Vocals – Klaus Blasquiz Notes Recorded in Paris in April 1970. Made in France by MPO Diffusion Harmonia Mundi Packaged in a double jewel case with 8-page booklet. -

King Crimson Collectors' Club (1969-1974)

King Crimson Collectors' Club (1969-1974) Scritto da Gianluca Livi Mercoledì 30 Marzo 2016 19:23 King Crimson 1 / 10 King Crimson Collectors' Club (1969-1974) Scritto da Gianluca Livi Mercoledì 30 Marzo 2016 19:23 Collectors' Club (1969-1974) di Gianluca Livi Articolo originariamente apparso in due puntate sui nn. 35 e 37 (rispettivamente Marzo/Aprile e Luglio/Agosto del 2008) di "Musikbox. Rivista di cultura musicale e guida ragionata al collezionismo", qui pubblicato, con alcune varianti, per gentile concessione dell'autore. Premessa (2008) Alla fine degli anni '90, stanco dei bootleg, Robert Fripp decise di commercializzare ufficialmente alcuni live dei King Crimson su cd, muovendo dal presupposto che, se fino a quel momento i fan avevano acquistato materiale del gruppo dal vivo di scarsa qualità, facendo guadagnare esclusivamente biechi 2 / 10 King Crimson Collectors' Club (1969-1974) Scritto da Gianluca Livi Mercoledì 30 Marzo 2016 19:23 imprenditori pirata, poteva egli stesso vendere le medesime esibizioni, ufficializzandone l'uscita sul mercato discografico e, congiuntamente, perseguendo anche un (legittimo) fine di lucro. Poiché anche parte delle registrazioni in suo possesso erano qualitativamente scadenti, conscio dell'impossibilità di immetterle nel mercato senza suscitare polemiche, decise di distribuirle solo agli iscritti di un club, il cosiddetto “Collector's Club”. Coloro che vi avessero aderito, previo versamento di una cifra iniziale abbastanza consistente, avrebbero ricevuto i titoli pubblicati di volta in volta, vedendosi scalato il valore di ogni singolo disco dalla quota d'iscrizione. L'iniziativa andò avanti con ottimi risultati fino al 2002, quando - abbandonato definitivamente il metodo dell'iscrizione al Club - i cd furono inseriti nel catalogo della DGM, unitamente ad album ufficiali dei Crimson e di altri artisti della scuderia. -

Concert: Carmina Burana by Carl Orff Ithaca College Choral Union

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 4-17-2005 Concert: Carmina Burana by Carl Orff Ithaca College Choral Union Ithaca College Symphony Orchestra Lawrence Doebler Jeffrey Grogan Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Ithaca College Choral Union; Ithaca College Symphony Orchestra; Doebler, Lawrence; and Grogan, Jeffrey, "Concert: Carmina Burana by Carl Orff" (2005). All Concert & Recital Programs. 4790. https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/4790 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. ITHACA COLLEGE CHORAL UNION ITHACA COLLEGE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Lawrence Doebler, conductor CARMINA BURANA by Carl Orff Randie Blooding, baritone Deborah Montgomery-Cove, soprano Carl Johengen, tenor Ithaca College Women's Chorale, Janet Galvan, conductor Ithaca College Chorus, Janet Galvan, conductor Ithaca College Choir, Lawrence Doebler, conductor Ithaca College Symphony Orchestra, Jeffrey Grogan, conductor Charis Dimaris and Read Gainsford, pianists Members of the Ithaca Children's Choir Community School of Music and Arts Janet Galvan, artistic director Verna Brummett, conductor Ford Hall Sunday, April 17, 2005 4:00 p.m. ITHACA THE OVERTURE TO THE SCHOOL FOR SCANDAL Samuel Barber Ithaca College Symphony -

78071 187 14782.Pdf

03 "Se han convertido en una de esas bandas que están más allá de los géneros" “Tuvo muy buen muy recibimiento, pero casi inmediatamente“Tuvo después se transformó en una rareza, era difícil de pillar. id Smith, colaborador de las presti- ro 30, pensé que sería bueno hacer la versión que ejercen escapa a los confines del rock progresivo y giosas revistas Prog Magazine, MOJO, nueva para esa fecha, veinte años después. Por creo que la razón es que la música creada por la banda Classic Rock y Record Collector —en- fortuna, fui capaz de sacarlo a tiempo”, dice desde los sesenta y setentas, hasta los años ochenta, ha tre otras— mantuvo desde el año 1999 riendo. Esquizoides en el siglo XXI cubierto mucho terreno estilísticamente. No solo han un blog en el sitio oficial de King Crim- tocado un único tipo de música. Los discos que van des- Sson, posteriormente llamado Krimson News y -Imagino que nunca pensaste ver a King Crim- de In the court of the Crimson King hasta Discipline en luego Postcards from the yellow room. En el son activo 50 años después de su creación. Al el 81 -e incluso más allá, como Thrak en 1994-, casi to- año 2001 editó la biografía titulada In the court comienzo el proyecto se disolvió apenas se lan- dos suenan diferentes, en especial los primeros cuatro. of King Crimson, coincidiendo con el aniversa- zó el disco debut, y ha pasado por muchos quie- Incluso así, todos suenan como King Crimson. rio número 30 de la banda. ¿Por qué? “La res- bres en su historia. -

Kodály and Orff: a Comparison of Two Approaches in Early Music Education

ZKÜ Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, Cilt 8, Sayı 15, 2012 ZKU Journal of Social Sciences, Volume 8, Number 15, 2012 KODÁLY AND ORFF: A COMPARISON OF TWO APPROACHES IN EARLY MUSIC EDUCATION Yrd.Doç.Dr. Dilek GÖKTÜRK CARY Karabük Üniversitesi Safranbolu Fethi Toker Güzel Sanatlar ve Tasarım Fakültesi Müzik Bölümü [email protected] ABSTRACT The Hungarian composer and ethnomusicologist Zoltán Kodály (1882-1967) and the German composer Carl Orff (1895-1982) are considered two of the most influential personalities in the arena of music education during the twentieth-century due to two distinct teaching methods that they developed under their own names. Kodály developed a hand-sign method (movable Do) for children to sing and sight-read while Orff’s goal was to help creativity of children through the use of percussive instruments. Although both composers focused on young children’s musical training the main difference between them is that Kodály focused on vocal/choral training with the use of hand signs while Orff’s main approach was mainly on movement, speech and making music through playing (particularly percussive) instruments. Finally, musical creativity via improvisation is the main goal in the Orff Method; yet, Kodály’s focal point was to dictate written music. Key Words: Zoltán Kodály, Carl Orff, The Kodály Method, The Orff Method. KODÁLY VE ORFF: ERKEN MÜZİK EĞİTİMİNDE KULLANILAN İKİ METODUN BİR KARŞILAŞTIRMASI ÖZET Macar besteci ve etnomüzikolog Zoltán Kodály (1882-1967) ve Alman besteci Carl Orff (1895-1982) geliştirmiş oldukları farklı 2 öğretim metodundan dolayı 20. yüzyılda müzik eğitimi alanında en etkili 2 kişi olarak anılmaktadırlar. Kodály çocukların şarkı söyleyebilmeleri ve deşifre yapabilmeleri için el işaretleri metodu (gezici Do) geliştirmiş, Orff ise vurmalı çalgıların kullanımı ile çocukların yaratıcılıklarını geliştirmeyi hedef edinmiştir. -

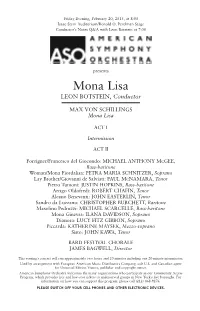

Mona Lisa LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor

Friday Evening, February 20, 2015, at 8:00 Isaac Stern Auditorium/Ronald O. Perelman Stage Conductor’s Notes Q&A with Leon Botstein at 7:00 presents Mona Lisa LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor MAX VON SCHILLINGS Mona Lisa ACT I Intermission ACT II Foreigner/Francesco del Giocondo: MICHAEL ANTHONY MCGEE, Bass-baritone Woman/Mona Fiordalisa: PETRA MARIA SCHNITZER, Soprano Lay Brother/Giovanni de Salviati: PAUL MCNAMARA, Tenor Pietro Tumoni: JUSTIN HOPKINS, Bass-baritone Arrigo Oldofredi: ROBERT CHAFIN, Tenor Alessio Beneventi: JOHN EASTERLIN, Tenor Sandro da Luzzano: CHRISTOPHER BURCHETT, Baritone Masolino Pedruzzi: MICHAEL SCARCELLE, Bass-baritone Mona Ginevra: ILANA DAVIDSON, Soprano Dianora: LUCY FITZ GIBBON, Soprano Piccarda: KATHERINE MAYSEK, Mezzo-soprano Sisto: JOHN KAWA, Tenor BARD FESTIVAL CHORALE JAMES BAGWELL, Director This evening’s concert will run approximately two hours and 20 minutes including one 20-minute intermission. Used by arrangement with European American Music Distributors Company, sole U.S. and Canadian agent for Universal Edition Vienna, publisher and copyright owner. American Symphony Orchestra welcomes the many organizations who participate in our Community Access Program, which provides free and low-cost tickets to underserved groups in New York’s five boroughs. For information on how you can support this program, please call (212) 868-9276. PLEASE SWITCH OFF YOUR CELL PHONES AND OTHER ELECTRONIC DEVICES. FROM THE Music Director The Stolen Smile DVDs or pirated videos. Opera is the by Leon Botstein one medium from the past that resists technological reproduction. A concert This concert performance of Max von version still represents properly the Schillings’ 1915 Mona Lisa is the latest sonority and the multi-dimensional installment of a series of concert perfor- aspect crucial to the operatic experi- mances of rare operas the ASO has pio- ence. -

Tapestry of Light a Holiday Celebration

EPISODE FOUR TAPESTRY OF LIGHT: A HOLIDAY CELEBRATION A MESSAGE FROM OUR PRESIDENT & CEO We welcome you to Heinz Hall to enjoy the music and traditions of the holiday season with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra. While we can’t gather together at Heinz Hall this year, we are excited to offer Front Row: Tapestry of Light, A Holiday Celebration to offer some comfort and joy during these uncertain times. This year’s program has old favorites – and new delights. Principal Pops Conductor Byron Stripling welcomes special guest vocalist Vanessa Campagna, a global star and a Beaver County native, who was discovered by Marvin Hamlisch, the PSO’s first Principal Pops Conductor. Byron also showcases his amazing trumpet playing in special performances of “Joy to the World” and an improvisation on the theme from “Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy.” The glorious brass section of the PSO is featured in three pieces, and the PSO is joined by members of the Pittsburgh Youth Chorus and a dancer from Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre School for special performances. Valerie Coleman’s Umoja (Swahili for “unity” or “togetherness”) is played by the PSO’s flute section. And, the celebration wouldn’t be complete without the annual tradition of a sing-along! We’re also very proud to present our first ever virtual Sensory Friendly Holiday Concert. This will be the Pittsburgh Symphony’s sixth season offering sensory friendly concerts, and our second Sensory Friendly Holiday Concert. Open to all, our sensory friendly performances are customized especially for those with autism spectrum disorders or who have other disabilities that create sensory sensitivities. -

Magma Live Mp3, Flac, Wma

Magma Live mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz / Rock Album: Live Country: US Released: 1989 Style: Jazz-Rock, Avantgarde, Prog Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1936 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1880 mb WMA version RAR size: 1643 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 704 Other Formats: MMF MP4 AU ADX VOC MP3 MPC Tracklist 1 Köhntark 31:00 2 Kobah 6:22 3 Lïhns 4:53 4 Hhaï 8:48 5 Mëkanïk Zaïn 18:11 Companies, etc. Recorded At – Taverne de l'Olympia Remastered At – Charly Studios Phonographic Copyright (p) – The Tomato Music Company, Ltd. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Charly Licensing Aps Copyright (c) – Charly Licensing Aps Record Company – Artistry Music Limited Marketed By – Snapper Music plc Distributed By – Snapper Music plc Manufactured By – Sound Performance Credits Bass – Bernard Paganotti Composed By, Drums – Christian Vander Guitar – Gabrid Federow* Keyboards – Benoit Widemann*, Jean-Pol Asseline* Producer [Produced By] – Giorgio Gomelsky Violin – Didier Lockwood Vocals [Vocal] – Klaus Blasquiz, Stella Vander Notes "To create music which defies time, we have pledged our material and inmaterial being to Magma, to Unïẁerïa Zekt, and to the Kreuhn Köhrmahn for the rest.... The music of Magma is like a mirror where everyone can see a reflection of who he is." Recorded live at the Taverne de l'Olympia in Paris between June 1 and June 5, 1975 Digitally Remastered at Charly Studios [Tracks] ℗ 1978 Tomato Music Co. Ltd. This compilation: ℗ 2001 Charly Licensing Aps © 2001 Charly Licensing Aps Country of origin UK. - Made in the E.U. Artistry Music Limited Distributed and Marketed by Snapper Music plc SNAP 008 CD [on tray card, spines and disc] CPCD 8171 [in booklet] ― Issued in a standard jewel case including a foldout insert. -

Le Nouveau Festival Du Centre Pompidou

EXPOSITIONS, SPECTACLES, CINÉMA, CONFÉRENCES ET PERFORMANCES 20 FÉVRIER - 11 MARS 2013 LE NOUVEAU FESTIVAL DU CENTRE POMPIDOU SOMMAIRE LE NOUVEAU FESTIVAL DU CENTRE POMPIDOU KHHHHHHH LA CLAIRIÈRE Langues imaginaires et inventées, Une proposition de Fanny de Chaillé une proposition de Bernard Blistène, et de Nadia Lauro QUATRIÈME ÉDITION Mica Gherghescu, JeanCharles Hameau et Mélanie Lerat (ESPACE 315) P 2225 (GALERIE SUD, PETITE SALLE) Le Nouveau festival a désormais quatre ans et démontre, cette fois P 47 BOOK MACHINE (PARIS) encore, sa capacité à se renouveler et à faire bouger les lignes Une proposition de Christophe Boutin, WUHS DIS NOW? Mélanie Scarciglia et Patrick Javault de la création artistique. Langues imaginaires et inventées au cinéma, une proposition (FORUM 1, PETITE SALLE, CINÉMA 2) P 2629 Quelque cent invités vont se retrouver au fil de trois semaines que nous de Judith Revault d’Allonnes souhaitons intenses et riches de découvertes. Pluridisciplinaire (GALERIE SUD, CINÉMA 1) SPECTACLE VIVANT P 811 Danse, musique, théâtre et fort d’avoir su se construire des fondamentaux du Centre et performance Pompidou, le Nouveau festival est désormais un rendezvous essentiel KOBAÏEN et généreux, inventif et prospectif. Il s’attache à nous proposer Musique et langues imaginaires, (GRANDE SALLE) P 3031 une proposition de Céline Chouffot, des formes inédites. Il est à l’écoute de celles et ceux qui s’attachent Sara Dufour et Delphine Le Gatt JEUNE PUBLIC / MÉDIATION à renouveler les modes d’expression et à élargir la perception (GALERIE SUD) P 3233 des arts visuels du temps présent. P 1213 AGENDA TELL ME… , GUY DE COINTET P 3437 Je l’ai souhaité ainsi afin de réaffirmer les valeurs essentielles Une proposition de Sophie Duplaix du Centre Pompidou, un lieu que son créateur rêvait d’attacher et Didier Schulmann ABSTRACT P 38 aux différents aspects de la création, sensible à l’histoire (GALERIE SUD, GRANDE SALLE) et constamment prospectif. -

MAGMA Conversation Avec Klaus Blasquiz

1977 MAGMA - Rock & Folk n° 120 – Janvier MAGMA Autre affaire à suivre, et l'on commence à en avoir l'habitude. Magma qui a été de nouveau réduit à l'état de duo est, de nouveau en train de se reconstituer. Au concert de Spheroe, il y avait Klaus et Georges Letton ostensiblement venus là pour recruter; il a même été un temps question que Magma ait deux batteurs. Les musiciens de Spheroe ont décliné l'offre que d'autres, parfois récidivistes, ont acceptée. Nous en reparlerons. En attendant, il est fortement question d'un album solo de Vander. Rock & Folk n° 120 - Janvier 1977 Conversation avec Klaus Blasquiz - ATEM n° 9 – Avril Conversation avec Klaus Blasquiz MAGMA A JAMAIS. Un silence long de quelques mois a suivi le départ de Janick Top, un retrait volontaire de la scène musicale mise à profit par Christian Vander et Klaus Blasquiz pour réunir autour d'eux de nouveaux musiciens afin de porter encore plus loin - et d'une manière sensiblement différente - leur ENERGIE, de communiquer partie ou totalité de la FOI qui les anime… C'est la Bretagne que MAGMA a choisi pour présenter son nouveau visage, et c'est là que Klaus Blasquiz s'est gentiment prêté au jeu des questions réponses… Atem : Etes-vous satisfait de votre tournée avec la nouvelle formation ici, en Bretagne ? KB : Au niveau de la Bretagne, c'est certainement nouveau, mais c'est nouveau aussi à notre niveau. Le groupe est pratiquement neuf et original, à part le pianiste qui était déjà là il y a 2 ans. -

Interview De Christian Vander. George Allen Et Robert Parson 22 Avril 1995

1995 Christian Vander - George Allen & Robert Parson - 22.04.95 (FR) Interview de Christian Vander. George Allen et Robert Parson 22 avril 1995 G.A. : L'emblème de Magma représente-t-il un oiseau, ou bien est-il abstrait ? C.V. : En le créant, je n'ai jamais pensé à un oiseau. J'avais en moi l'idée d'un symbole, d'un emblème, et je l'ai seulement noté sur un morceau de papier, c'était juste une esquisse. Au début, mon idée était de faire quelque chose qui ressemblerait à un vêtement égyptien. Ca devait ressembler à un morceau de tissu ou des feuilles de métal articulées qui envelopperaient le corps au niveau de la cage thoracique. Ca devait ressembler au plastron d'une armure, mais être souple et non pas rigide. G.A. : Le nom Magma est-il en kobaïen ou bien est-ce une référence à la lave ? Est-ce que le nom reflète le style du groupe ? C.V. : Oui, c'est une référence directe à la lave. En 1966, j'avais écrit un morceau et je faisais déjà partie d'un groupe avec Bernard Paganotti, qui est devenu bassiste de Magma. Déjà à l'époque, je cherchais le mot juste. Le morceau que j'avais écrit à l'époque s'intitulait "Nogma". Je cherchais le mot "Magma", sans savoir que c'était ce mot précis que je cherchais. Un jour, alors que le groupe n'avait pas encore de nom et que nous attendions devant un club parisien assez connu, la direction m'a dit que si nous n'avions pas de nom, nous ne pourrions pas jouer. -

[email protected]

Bratislava Music Festival 48th Year 28. 9. 2013 – 14. 10. 2012 Main organizer Slovak Philharmonic as delegated by and with financial support from the Ministry of Culture of the Slovak Republic The festival is held under the patronage of Ivan Gašparovič, the President of the Slovak Republic Honorary President of the BMF – Edita Gruberova Friday, 28th September 7.30 p. m. Concert Hall of the Slovak Philharmonic Opening Concert of the 48th Year of the BMF Slovak Philharmonic Emmanuel Villaume, conductor Sarah Chang, violin Johannes Brahms Violin Concerto in D Major, Op. 77 Richard Strauss Also sprach Zarathustra, tone poem, Op. 30 Saturday, 29th September 5.00 p. m. St. Martin’s Cathedral Solamente naturali Bratislava Boys’ Choir Miloš Valent, artistic leader Magdaléna Rovňáková, conductor Gabriel Rovňák, conductor Miriam Garajová, soprano Alexander Schneider, countertenor Matej Slezák, tenor Tomáš Šelc, bass-baritone Ondrej Bajan, bass and soloists of the Bratislava Boys’ Choir Marc-Antoine Charpentier, François Couperin, Simon Brixi, Juan Cererols, Georg Friedrich Händel, Franz Xaver, Tost Johann Pachelbel Ľuboš Bernáth O mitissima virgo Maria for baritone solo, male choir and orchestra premiere Sunday, 30th September 4.00 p. m. Concert Hall of the Slovak Philharmonic Organ Recital Ján Vladimír Michalko Franz Schmidt, Max Reger, Alexandre Guilmant, Louis Vierne, Charles Tournemire 7.30 p. m. Small Hall of the Slovak Philharmonic Quasars Ensemble Ivan Buffa, artistic leader / conductor Eva Šušková, soprano František Výrostko, reciter Maja Hriešik, scenic collaboration Ilja Zeljenka Metamorphoses XV for reciter and 9 instruments Alexander Albrecht Sonatina for Eleven Instruments Arnold Schönberg Pierrot lunaire Op. 21 Monday, 1st October 7.30 p.