Preparing for Research: Metatheoretical Considerations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Logic and Its Metatheory

Logic and its Metatheory Philosophy 432 Spring 2017 T & TH: 300-450pm Olds Hall 109 Instructor Information Matthew McKeon Office: 503 South Kedzie Hall Office hours: 1-2:30pm on T & TH and by appointment. Telephone: Dept. Office—355-4490 E-mail: [email protected] Required Text Courseware Package (Text plus CD software): Jon Barwise and John Etchemendy. Language, Proof and Logic. 2nd edition. Stanford, CA: CLSI Publications, 2011. The courseware package includes several software tools that students will use to complete homework assignments and the self-diagnostic exercises from the text. DO NOT BUY USED BOOKS, BECAUSE THEY LACK THE CD, WHICH CONTAINS THE SOFTWARE. The software, easy to learn and use, makes some of the more technical aspects of symbolic logic accessible to introductory students and it is fun to use (or so I think). It is OK to have an earlier edition of the text as long as you have the CD with the password key that will allow you to access the text’s online site (https://ggweb.gradegrinder.net/lpl). Here you can update the software suite and download the 2nd edition of the text. At the site you can also purchase the software and an electronic version of the text. Primary Course Objectives • Deepen your understanding of the concept of logical consequence and sharpen your ability to see that one sentence is a logical consequence of others. • Introduce you to the basic methods of proof (both formal and informal), and teach you how to use them effectively to prove that one sentence is a logical consequence of others. -

Mechanized Metatheory Revisited

Journal of Automated Reasoning manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) Mechanized metatheory revisited Dale Miller Draft: August 29, 2019 Abstract When proof assistants and theorem provers implement the metatheory of logical systems, they must deal with a range of syntactic expressions (e.g., types, for- mulas, and proofs) that involve variable bindings. Since most mature proof assistants do not have built-in methods to treat bindings, they have been extended with various packages and libraries that allow them to encode such syntax using, for example, de Bruijn numerals. We put forward the argument that bindings are such an intimate aspect of the structure of expressions that they should be accounted for directly in the underlying programming language support for proof assistants and not via packages and libraries. We present an approach to designing programming languages and proof assistants that directly supports bindings in syntax. The roots of this approach can be found in the mobility of binders between term-level bindings, formula-level bindings (quantifiers), and proof-level bindings (eigenvariables). In particular, the combination of Church's approach to terms and formulas (found in his Simple Theory of Types) and Gentzen's approach to proofs (found in his sequent calculus) yields a framework for the interaction of bindings with a full range of logical connectives and quantifiers. We will also illustrate how that framework provides a direct and semantically clean treatment of computation and reasoning with syntax containing bindings. Some imple- mented systems, which support this intimate and built-in treatment of bindings, will be briefly described. Keywords mechanized metatheory, λ-tree syntax, mobility of binders 1 Metatheory and its mechanization Theorem proving|in both its interactive and automatic forms|has been applied in a wide range of domains. -

Nietzsche's Nonobjectivity on Planck's Quanta

Bellarmine University ScholarWorks@Bellarmine Undergraduate Theses Undergraduate Works 5-17-2019 Phantoms in Science: Nietzsche's Nonobjectivity on Planck's Quanta Donald Richard Dickerson III Bellarmine University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bellarmine.edu/ugrad_theses Part of the Chemistry Commons, Philosophy of Science Commons, and the Quantum Physics Commons Recommended Citation Dickerson, Donald Richard III, "Phantoms in Science: Nietzsche's Nonobjectivity on Planck's Quanta" (2019). Undergraduate Theses. 41. https://scholarworks.bellarmine.edu/ugrad_theses/41 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Works at ScholarWorks@Bellarmine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@Bellarmine. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. ¬¬PHANTOMS IN SCIENCE: NIETZSCHE’S NONOBJECTIVITY ON PLANCK’S QUANTA Honors Thesis Abstract What does Maxwell Planck's concept of phantomness suggest about the epistemological basis of science and how might a Nietzschean critique reveal solution to the weaknesses revealed? With his solution to Kirchoff's equation, Maxwell Planck launched the paradigm of quantum physics. This same solution undermined much of current understandings of science versus pseudoscience. Using Nietzsche's perspectivism and other philosophical critiques, Planck's answer to blackbody radiation is used to highlight the troubles with phantom problems in science and how to try to direct science towards a more holistic and complete scientific approach. D. Richard Dickerson III [email protected] 1 PHANTOMS IN SCIENCE: NIETZSCHE’S NONOBJECTIVITY ON PLANCK’S QUANTA INTRODUCTION The current understanding of science relies on stark contrasts between physics and metaphysics. -

METALOGIC METALOGIC an Introduction to the Metatheory of Standard First Order Logic

METALOGIC METALOGIC An Introduction to the Metatheory of Standard First Order Logic Geoffrey Hunter Senior Lecturer in the Department of Logic and Metaphysics University of St Andrews PALGRA VE MACMILLAN © Geoffrey Hunter 1971 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1971 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without permission. First published 1971 by MACMILLAN AND CO LTD London and Basingstoke Associated companies in New York Toronto Dublin Melbourne Johannesburg and Madras SBN 333 11589 9 (hard cover) 333 11590 2 (paper cover) ISBN 978-0-333-11590-9 ISBN 978-1-349-15428-9 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-15428-9 The Papermac edition of this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent, in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. To my mother and to the memory of my father, Joseph Walter Hunter Contents Preface xi Part One: Introduction: General Notions 1 Formal languages 4 2 Interpretations of formal languages. Model theory 6 3 Deductive apparatuses. Formal systems. Proof theory 7 4 'Syntactic', 'Semantic' 9 5 Metatheory. The metatheory of logic 10 6 Using and mentioning. Object language and metalang- uage. Proofs in a formal system and proofs about a formal system. Theorem and metatheorem 10 7 The notion of effective method in logic and mathematics 13 8 Decidable sets 16 9 1-1 correspondence. -

Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches W

Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches W. Lawrence Neuman Seventh Edition ISBN 10: 1-292-02023-7 ISBN 13: 978-1-292-02023-5 Pearson Education Limited Edinburgh Gate Harlow Essex CM20 2JE England and Associated Companies throughout the world Visit us on the World Wide Web at: www.pearsoned.co.uk © Pearson Education Limited 2014 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without either the prior written permission of the publisher or a licence permitting restricted copying in the United Kingdom issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. All trademarks used herein are the property of their respective owners. The use of any trademark in this text does not vest in the author or publisher any trademark ownership rights in such trademarks, nor does the use of such trademarks imply any affi liation with or endorsement of this book by such owners. ISBN 10: 1-292-02023-7 ISBN 13: 978-1-292-02023-5 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Printed in the United States of America 1251652012452813153673934312555911 PEARSON C U S T OM LIBRAR Y Table of Contents 1. Why Do Research? W. Lawrence Neuman 1 2. What Are the Major Types of Social Research? W. Lawrence Neuman 25 3. Theory and Research W. Lawrence Neuman 55 4. The Meanings of Methodology W. -

Postpositivism and Accounting Research : a (Personal) Primer on Critical Realism

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Online Australasian Accounting, Business and Finance Journal Volume 4 Issue 4 Australasian Accounting Business and Article 2 Finance Journal 2010 Postpositivism and Accounting Research : A (Personal) Primer on Critical Realism Jayne Bisman Charles Sturt University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/aabfj Copyright ©2010 Australasian Accounting Business and Finance Journal and Authors. Recommended Citation Bisman, Jayne, Postpositivism and Accounting Research : A (Personal) Primer on Critical Realism, Australasian Accounting, Business and Finance Journal, 4(4), 2010, 3-25. Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Postpositivism and Accounting Research : A (Personal) Primer on Critical Realism Abstract This paper presents an overview and primer on the postpositivist philosophy of critical realism. The examination of this research paradigm commences with the identification of the underlying motivations that prompted a personal exploration of critical realism. A brief review of ontology, epistemology and methodology and the research philosophies and methods popularly applied in accounting is then provided. The meta-theoretical basis of critical realism and the ontological and epistemological assumptions that go towards establishing the ‘truth’ and validity criteria underpinning this paradigm are detailed, and the relevance and potential applications of critical realism to accounting research are also discussed. The purpose of this discussion is to make a call to diversify the approaches to accounting research, and – specifically – ot assist researchers to realise the potential for postpositivist multiple method research designs in accounting. -

Chapter 1 Major Research Paradigms

Chapter 1 Major research paradigms Introduction The primary purpose of this text is to provide an overview of the research process and a guide to the options available to any researcher wishing to engage in that process. It has been said that too much time spent engaging in the ‘higher’ philosophical debate surrounding research limits the amount of actual research that gets done. All researchers have their work to do and ultimately it is the ‘doing’ that counts, but the debate is a fascinating one and it would be very remiss not to provide you with some level of intro- duction to it. If you find yourself reading this chapter and thinking ‘so what?’, take some time to examine the implications of a paradigm on the research process. What follows is a very brief discussion of the major research paradigms in the fields of information, communication and related disciplines. We are going to take a tour of three research paradigms: positivism, postpositivism and interpretivism. I had considered revising this for this edition but after extensive investigation into the developing discourse, I have decided that my basic belief has not been altered by these debates. There are those that lament the absence of a fourth par- adigm which covers the mixed-methods approach from this text, namely pragmatism, but try as I might I can find no philosophical underpinning for pragmatism that is not already argued within a postpositive axiology. For some this will be too much, for oth- ers too little. Those of you who want more can follow the leads at the end of the chapter; those of you who want less, please bear with me for the brief tour of the major research traditions of our dis cipline. -

Introduction to Positivism, Interpretivism and Critical Theory

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Introduction to positivism, interpretivism and critical theory Journal Item How to cite: Ryan, Gemma (2018). Introduction to positivism, interpretivism and critical theory. Nurse Researcher, 25(4) pp. 41–49. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c [not recorded] https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Accepted Manuscript Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.7748/nr.2018.e1466 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Introduction to positivist, interpretivism & critical theory Abstract Background There are three commonly known philosophical research paradigms used to guide research methods and analysis: positivism, interpretivism and critical theory. Being able to justify the decision to adopt or reject a philosophy should be part of the basis of research. It is therefore important to understand these paradigms, their origins and principles, and to decide which is appropriate for a study and inform its design, methodology and analysis. Aim To help those new to research philosophy by explaining positivism, interpretivism and critical theory. Discussion Positivism resulted from foundationalism and empiricism; positivists value objectivity and proving or disproving hypotheses. Interpretivism is in direct opposition to positivism; it originated from principles developed by Kant and values subjectivity. Critical theory originated in the Frankfurt School and considers the wider oppressive nature of politics or societal influences, and often includes feminist research. -

The Art of Metascience; Or, What Should a Psychological Theory Be?

First published in Towards Unification in Psychology, J. R. Royce (ed.), 1970. Extract, pp. 54–103. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. The Art of Metascience; or, What Should a Psychological Theory Be? Introduction In order not to lay false claims upon your attention, let me confess at once that the subtitle of this paper is intended more as a stimulus to curiosity than as a serious synopsis of the subject here to be addressed. I shall indeed be concerned at considerable length with the methodological character of psychological theories, but my prescriptions will focus upon process rather than product. Specifically, I shall offer some detailed judgments on how theorizing must be done—or, more precisely, what sorts of metatheorizing must accompany it—if the enterprise is to make a genuine contribution to science; and while on first impression these may seem like no more than the standard broad-spectrum abstractions of one who has nothing specific to say, I assure you that they envision realizable operations which, if practiced, would have a profound effect on our conceptual efficiency as psychologists. There are at least two formal dimensions along which discussions of psycho- logical theory can vary. One is level of abstraction, or substantivity of concern, with attention to specific extant theories (e.g. pointing out an inconsistency or clarifying an ambiguity in John Smiths’ theory of binocular psychokinesis) at one extreme, and philosophy-of-science type concerns for the nature and functioning of idealized theories in general, detached from any real-life instances, at the other. Distinct from this, though not wholly orthogonal to it, is a second dimension of metatheory which might be called acuity or penetration, and which concerns the degree to which the discussion makes a serious, intellectually responsible attempt to further our understanding of the matter with which it deals. -

PHI 1130 Environmental Ethics Cr

PHI 1130 Environmental Ethics Cr. 3 PHI - PHILOSOPHY Satisfies General Education Requirement: Cultural Inquiry, Philosophy Letters PHI 1010 Introduction to Philosophy Cr. 4 Is the natural world something to be valued in itself, or is its value Satisfies General Education Requirement: Cultural Inquiry, Philosophy exhausted by the uses human beings derive from it? This course Letters introduces students to some of the major views on the subject, Survey of some major questions that have occupied philosophers anthropocentric (human-centered) and non-anthropocentric. Offered throughout history, such as Does God exist? What is a good person? Do Yearly. we have free will? Is the mind the same as the brain? What can we really Restriction(s): Enrollment is limited to Undergraduate level students. know? Course will acquaint students with major figures both historical PHI 1200 Life and Death Cr. 3 and contemporary. Offered Every Term. Satisfies General Education Requirement: Cultural Inquiry, Philosophy PHI 1020 Honors Introduction to Philosophy Cr. 3-4 Letters Satisfies General Education Requirement: Cultural Inquiry, Honors Central philosophical and religious questions about life and death, and Section, Philosophy Letters the enterprise of answering these questions through reasoning and Survey of some major questions that have occupied philosophers argument. What is it to be alive, and to die? Do we cease to exist when throughout history, such as Does God exist? What is a good person? we die, or might we continue to exist in an afterlife following our deaths? Do we have free will? What can we really know? Course will acquaint Should we fear or regret the fact that we will die someday, or should we students with major figures both historical and contemporary. -

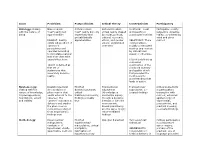

Issue Positivism Postpositivism Critical Theory Constructivism Participatory

Issue Positivism Postpositivism Critical Theory Constructivism Participatory Ontology: dealing Naive realism - Critical realism - Historical realism - Relativism - local Participative reality - with the nature of "real" reality but "real" reality but only virtual reality shaped and specific co- subjective-objective being apprehendible imperfectly and by social, political, constructed realities reality, co-created by probabilistically cultural, economic, mind and given REALIST: Reality apprehensible ethnic, and gender RELATIVIST: There cosmos exists independent of values; crystallized exists multiple, observer's over time socially constructed perceptions and realities ungoverned operates according by natural laws -- to immutable natural causal or otherwise. laws that often take cause/effect form. TRUTH is defined as consensus TRUTH is defined as construction of the that set of combined quantity statements that and quality of info accurately describe that provided the reality. most powerful understanding that leads to action. Epistemology: Dualist/objectivist Modified Transactional/ Transactional/ Critical subjectivity dealing with the (Knowledge is a dualist/objectivist; subjectivist subjectivist; co- in participatory nature of knowledge, phenomenon that critical (Knowledge is created findings transaction with its presuppositions, exists external to the tradition/community; created by inquiry cosmos; extended foundations, extent observer; the findings probably through a dynamic epistemology of and validity observer maintains a true interaction -

Pragmatism As a Research Paradigm and Its Implications for Social Work Research

social sciences $€ £ ¥ Article Pragmatism as a Research Paradigm and Its Implications for Social Work Research Vibha Kaushik * and Christine A. Walsh Faculty of Social Work, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB T2N 1N4, Canada * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 18 July 2019; Accepted: 3 September 2019; Published: 6 September 2019 Abstract: Debates around the issues of knowledge of, and for, social work and other social justice–oriented professions are not uncommon. More prevalent are the discussions around the ways by which social work knowledge is obtained. In recent years, social work scholars have drawn on the epistemology of pragmatism to present a case for its value in the creation of knowledge for social work and other social justice–oriented professions. The primary focus of this essay is on providing a critical review and synthesis of the literature regarding pragmatism as a research paradigm. In this essay, we analyze the major philosophical underpinnings and methodological challenges associated with pragmatism, synthesize the works of scholars who have contributed to the understanding of pragmatism as a research paradigm, articulate our thoughts about how pragmatism fits within social work research, and illustrate how it is linked to the pursuit of social justice. This article brings together a variety of perspectives to argue that pragmatism has the potential to closely engage and empower marginalized and oppressed communities and provide hard evidence for the macro level discourse. Keywords: pragmatism; pragmatic research; social justice research; social work research 1. Introduction In social research, the term “paradigm” is used to refer to the philosophical assumptions or to the basic set of beliefs that guide the actions and define the worldview of the researcher (Lincoln et al.