Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nietzsche's Nonobjectivity on Planck's Quanta

Bellarmine University ScholarWorks@Bellarmine Undergraduate Theses Undergraduate Works 5-17-2019 Phantoms in Science: Nietzsche's Nonobjectivity on Planck's Quanta Donald Richard Dickerson III Bellarmine University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bellarmine.edu/ugrad_theses Part of the Chemistry Commons, Philosophy of Science Commons, and the Quantum Physics Commons Recommended Citation Dickerson, Donald Richard III, "Phantoms in Science: Nietzsche's Nonobjectivity on Planck's Quanta" (2019). Undergraduate Theses. 41. https://scholarworks.bellarmine.edu/ugrad_theses/41 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Works at ScholarWorks@Bellarmine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@Bellarmine. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. ¬¬PHANTOMS IN SCIENCE: NIETZSCHE’S NONOBJECTIVITY ON PLANCK’S QUANTA Honors Thesis Abstract What does Maxwell Planck's concept of phantomness suggest about the epistemological basis of science and how might a Nietzschean critique reveal solution to the weaknesses revealed? With his solution to Kirchoff's equation, Maxwell Planck launched the paradigm of quantum physics. This same solution undermined much of current understandings of science versus pseudoscience. Using Nietzsche's perspectivism and other philosophical critiques, Planck's answer to blackbody radiation is used to highlight the troubles with phantom problems in science and how to try to direct science towards a more holistic and complete scientific approach. D. Richard Dickerson III [email protected] 1 PHANTOMS IN SCIENCE: NIETZSCHE’S NONOBJECTIVITY ON PLANCK’S QUANTA INTRODUCTION The current understanding of science relies on stark contrasts between physics and metaphysics. -

Preparing for Research: Metatheoretical Considerations

Chapter 3 In Chapter 2 a distinction was made between international and comparative librarianship and the scope of these two fields was outlined. In a sense we were running a little ahead of our material, since any such delimitation rests on certain Preparing for research: metatheoretical basic assumptions. These assumptions, of which we may or may not be aware, can be broadly labeled metatheoretical. They underlie methodological decisions and considerations the design and selection of research methods and techniques for specific projects. Such assumptions do not apply only to research, but are also worth bringing to the Outline surface in the context of international activities and relations in LIS. International initiatives that are undertaken without reflection on the assumptions held by the Metatheory, methodology and method partners risk unanticipated difficulties. Wertheimer (2009) recently illustrated this Metatheories in a discussion of the influence of North American educators on LIS education in Positivism Asia and pointed out that a critical understanding of library contexts in other Postpositivism countries is necessary. Interpretivism Multiple metatheories In this chapter1, the main emphasis is on the assumptions underlying research in The sociological dimension comparative librarianship. To a somewhat lesser extent they are also relevant to Disciplinary and paradigmatic influences Ethnocentricity research and professional practice in international librarianship. Extensive use is Language made here of literature from other comparative fields, especially comparative Multinational research education, which was a major early influence on comparative librarianship. The teleological dimension Positivism and postpositivism Interpretivism Metatheory, methodology and method Applied research The ontological dimension Hjørland (2005b:5) defines metatheories as “...theories about the description, Ontological stances investigation, analysis or criticism of the theories in a domain. -

Postpositivism and Accounting Research : a (Personal) Primer on Critical Realism

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Online Australasian Accounting, Business and Finance Journal Volume 4 Issue 4 Australasian Accounting Business and Article 2 Finance Journal 2010 Postpositivism and Accounting Research : A (Personal) Primer on Critical Realism Jayne Bisman Charles Sturt University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/aabfj Copyright ©2010 Australasian Accounting Business and Finance Journal and Authors. Recommended Citation Bisman, Jayne, Postpositivism and Accounting Research : A (Personal) Primer on Critical Realism, Australasian Accounting, Business and Finance Journal, 4(4), 2010, 3-25. Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Postpositivism and Accounting Research : A (Personal) Primer on Critical Realism Abstract This paper presents an overview and primer on the postpositivist philosophy of critical realism. The examination of this research paradigm commences with the identification of the underlying motivations that prompted a personal exploration of critical realism. A brief review of ontology, epistemology and methodology and the research philosophies and methods popularly applied in accounting is then provided. The meta-theoretical basis of critical realism and the ontological and epistemological assumptions that go towards establishing the ‘truth’ and validity criteria underpinning this paradigm are detailed, and the relevance and potential applications of critical realism to accounting research are also discussed. The purpose of this discussion is to make a call to diversify the approaches to accounting research, and – specifically – ot assist researchers to realise the potential for postpositivist multiple method research designs in accounting. -

Chapter 1 Major Research Paradigms

Chapter 1 Major research paradigms Introduction The primary purpose of this text is to provide an overview of the research process and a guide to the options available to any researcher wishing to engage in that process. It has been said that too much time spent engaging in the ‘higher’ philosophical debate surrounding research limits the amount of actual research that gets done. All researchers have their work to do and ultimately it is the ‘doing’ that counts, but the debate is a fascinating one and it would be very remiss not to provide you with some level of intro- duction to it. If you find yourself reading this chapter and thinking ‘so what?’, take some time to examine the implications of a paradigm on the research process. What follows is a very brief discussion of the major research paradigms in the fields of information, communication and related disciplines. We are going to take a tour of three research paradigms: positivism, postpositivism and interpretivism. I had considered revising this for this edition but after extensive investigation into the developing discourse, I have decided that my basic belief has not been altered by these debates. There are those that lament the absence of a fourth par- adigm which covers the mixed-methods approach from this text, namely pragmatism, but try as I might I can find no philosophical underpinning for pragmatism that is not already argued within a postpositive axiology. For some this will be too much, for oth- ers too little. Those of you who want more can follow the leads at the end of the chapter; those of you who want less, please bear with me for the brief tour of the major research traditions of our dis cipline. -

Introduction to Positivism, Interpretivism and Critical Theory

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Introduction to positivism, interpretivism and critical theory Journal Item How to cite: Ryan, Gemma (2018). Introduction to positivism, interpretivism and critical theory. Nurse Researcher, 25(4) pp. 41–49. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c [not recorded] https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Accepted Manuscript Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.7748/nr.2018.e1466 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Introduction to positivist, interpretivism & critical theory Abstract Background There are three commonly known philosophical research paradigms used to guide research methods and analysis: positivism, interpretivism and critical theory. Being able to justify the decision to adopt or reject a philosophy should be part of the basis of research. It is therefore important to understand these paradigms, their origins and principles, and to decide which is appropriate for a study and inform its design, methodology and analysis. Aim To help those new to research philosophy by explaining positivism, interpretivism and critical theory. Discussion Positivism resulted from foundationalism and empiricism; positivists value objectivity and proving or disproving hypotheses. Interpretivism is in direct opposition to positivism; it originated from principles developed by Kant and values subjectivity. Critical theory originated in the Frankfurt School and considers the wider oppressive nature of politics or societal influences, and often includes feminist research. -

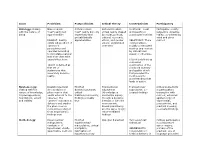

Issue Positivism Postpositivism Critical Theory Constructivism Participatory

Issue Positivism Postpositivism Critical Theory Constructivism Participatory Ontology: dealing Naive realism - Critical realism - Historical realism - Relativism - local Participative reality - with the nature of "real" reality but "real" reality but only virtual reality shaped and specific co- subjective-objective being apprehendible imperfectly and by social, political, constructed realities reality, co-created by probabilistically cultural, economic, mind and given REALIST: Reality apprehensible ethnic, and gender RELATIVIST: There cosmos exists independent of values; crystallized exists multiple, observer's over time socially constructed perceptions and realities ungoverned operates according by natural laws -- to immutable natural causal or otherwise. laws that often take cause/effect form. TRUTH is defined as consensus TRUTH is defined as construction of the that set of combined quantity statements that and quality of info accurately describe that provided the reality. most powerful understanding that leads to action. Epistemology: Dualist/objectivist Modified Transactional/ Transactional/ Critical subjectivity dealing with the (Knowledge is a dualist/objectivist; subjectivist subjectivist; co- in participatory nature of knowledge, phenomenon that critical (Knowledge is created findings transaction with its presuppositions, exists external to the tradition/community; created by inquiry cosmos; extended foundations, extent observer; the findings probably through a dynamic epistemology of and validity observer maintains a true interaction -

Pragmatism As a Research Paradigm and Its Implications for Social Work Research

social sciences $€ £ ¥ Article Pragmatism as a Research Paradigm and Its Implications for Social Work Research Vibha Kaushik * and Christine A. Walsh Faculty of Social Work, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB T2N 1N4, Canada * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 18 July 2019; Accepted: 3 September 2019; Published: 6 September 2019 Abstract: Debates around the issues of knowledge of, and for, social work and other social justice–oriented professions are not uncommon. More prevalent are the discussions around the ways by which social work knowledge is obtained. In recent years, social work scholars have drawn on the epistemology of pragmatism to present a case for its value in the creation of knowledge for social work and other social justice–oriented professions. The primary focus of this essay is on providing a critical review and synthesis of the literature regarding pragmatism as a research paradigm. In this essay, we analyze the major philosophical underpinnings and methodological challenges associated with pragmatism, synthesize the works of scholars who have contributed to the understanding of pragmatism as a research paradigm, articulate our thoughts about how pragmatism fits within social work research, and illustrate how it is linked to the pursuit of social justice. This article brings together a variety of perspectives to argue that pragmatism has the potential to closely engage and empower marginalized and oppressed communities and provide hard evidence for the macro level discourse. Keywords: pragmatism; pragmatic research; social justice research; social work research 1. Introduction In social research, the term “paradigm” is used to refer to the philosophical assumptions or to the basic set of beliefs that guide the actions and define the worldview of the researcher (Lincoln et al. -

Logical Empiricism

Logical Empiricism HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARY PERSPECTIVES Edited by Paolo Parrini, University ofFlorence Wesley C. Salmon, University ofPittsburgh Merrilee H. Salmon, University of Pittsburgh UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH PRESS This book is dedicated to the memory of Wesley C . Salmon 1925-2001 Published by the University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, P&, 15260 Copyright ® 2003, University of Pittsburgh Press All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Printed on add-free paper 10987654321 ISBN 0 - 8n9- 4194-5 Contents Preface Introduction r Paolo Parrini and Wesley Salmon I. Turning Points and Fundamental Controversies rt A Turning Point in Philosophy : Carnap-Cassirer-Heidegger 13 Michael Friedman Carnap's "Elimination of Metaphysics through Logical Analysis of Language" : A Retrospective Consideration of the Relationship between Continental and Analytic Philosophy 30 Gottfried Gabriel Schlick and Husserl on the Essence of Knowledge 43 Roberta Lanfredini Carnap versus Gbdel on Syntax and Tolerance 57 S. Awodey and A. W Carus II. On the Origins and Development of the Vienna Circle 65 On the Austrian Roots of Logical Empiricism: The Case of the First Vienna Circle 67 Thomas Uebel On the International Encyclopedia, the Neurath-Carnap Disputes, and the Second World War 94 George Reisch Carl Gustav Hempel : Pragmatic Empiricist log Gereon Wolters III. The Riddle of Wittgenstein 123 The Methods of the Tractatus: Beyond Positivism and Metaphysics? 125 David G. Stern IV Philosophy of Physics 157 Two Roads from Kant : Cassirer, Reichenbach, and General Relativity ' 159 T A. Ryckman Vienna Indeterminism II : From Exner to Frank and von Mises 194 'Michael Stoltzner V. The Mind-Body Problem 231 The Mind-Body Problem in the Origin of Logical Empiricism : Herbert Feigl and Psychophysical Parallelism 233 Michael Heidelberger Logical Positivism and the Mind-Body Problem 263 Jaegwon Kim VI. -

The Redundancy of Positivism As a Paradigm for Nursing Research

Title Page Journal: Nursing Philosophy Title: The Redundancy of Positivism as a Paradigm for Nursing Research Running Title: The Redundancy of Positivism Authors: Margarita Corry, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Trinity College Dublin, Ireland. Sam Porter, Department of Social Sciences and Social Work, Bournemouth University, England (corresponding author: [email protected], (0044) 1202 964107). Hugh McKenna, Institute of Nursing and Health Research, Ulster University, Northern Ireland. No acknowledgements. No conflicts of interest to report. No funding attained. Title The Redundancy of Positivism as a Paradigm for Nursing Research. ABSTRACT New nursing researchers are faced with a smorgasbord of competing methodologies. Sometimes they are encouraged to adopt the research paradigms beloved of their senior colleagues. This is a problem if those paradigms are no longer of contemporary methodological relevance. The aim of this paper is to provide clarity about current research paradigms. It seeks to interrogate the continuing viability of positivism as a guiding paradigm for nursing research. It does this by critically analysing the methodological literature. Five major paradigms are addressed: the positivist; the interpretivist / constructivist; the transformative; the realist; and the postpositivist. Acceptance of interpretivist, transformative or realist approaches necessarily entails wholesale rejection of positivism, while acceptance of postpositivism involves its partial rejection. Postpositivism has superseded positivism -

And International Relations Scholarship: from Applied Reflexivity to Reflexivism

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Apollo THE “PROBLEM OF VALUES” AND INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS SCHOLARSHIP: FROM APPLIED REFLEXIVITY TO REFLEXIVISM Inanna Hamati-Ataya International Studies Review 13(2): 259-287. 2011. Abstract In light of recent discussions of cognitive and ethical dilemmas related to International Relations (IR) scholarship, this paper proposes to engage the “problem of values” in IR as a composite question whose cognitive treatment requires the objectivation of the more profoundly institutional and social processes that subtend its emergence and evolution within the discipline. This analysis is hereby offered as an exercise in reflexive scholarship. Insofar as the question of values constitutes a defining cognitive and moral concern for reflexive knowledge itself, the paper also points to the need for its reformulation within an epistemic framework that is capable of moving beyond reflexivity to Reflexivism proper, understood as a systematic socio-cognitive practice of reflexivity. INTRODUCTION International Relations (IR) scholarship finds itself today in a situation that is reminiscent of the one in which Max Weber (2004[1918/1919]) found the German academy a century ago, with no clear standards for the definition of the scholar’s relationship to the public sphere, and of scholarship’s social and moral role∗. The International Studies Association’s (ISA) 2007 Annual Meeting, which called on the IR community to reflect on issues of “political involvement,” “scientific detachment,” “moral responsibility,” and “ethical standards” (Tickner and Tsygankov 2008:661) is the institutional manifestation of this current state of affairs, which has recently been questioned or rejected by scholars promoting a more “reflexive” engagement with the commitments that underlie or result from IR’s objectivation of world politics (Smith 2002 and 2004; Agathangelou and Ling 2004; Widmaier 2004; Tickner 2006; Lynch 2008; Ackerly and True 2008; Ish-Shalom 2008). -

THREE COMPONENTS INVOLVED in a DESIGN Philosophical Worldviews

01-Creswell (RD)-45593:01-Creswell (RD)-45593.qxd 6/20/2008 4:36 PM Page 5 The Selection of a Research Design 5 THREE COMPONENTS INVOLVED IN A DESIGN Two important components in each definition are that the approach to research involves philosophical assumptions as well as distinct methods or procedures. Research design, which I refer to as the plan or proposal to conduct research, involves the intersection of philosophy, strategies of inquiry, and specific methods. A framework that I use to explain the inter- action of these three components is seen in Figure 1.1. To reiterate, in planning a study, researchers need to think through the philosophical worldview assumptions that they bring to the study, the strategy of inquiry that is related to this worldview, and the specific methods or procedures of research that translate the approach into practice. Philosophical Worldviews Although philosophical ideas remain largely hidden in research (Slife & Williams, 1995), they still influence the practice of research and need to be identified. I suggest that individuals preparing a research proposal or plan make explicit the larger philosophical ideas they espouse. This information will help explain why they chose qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods Selected Strategies of Inquiry Philosophical Qualitative strategies Worldviews (e.g., ethnography) Postpositive Quantitative strategies Social construction (e.g., experiments) Advocacy/participatory Mixed methods startegies Pragmatic (e.g., sequential) Research Designs Qualitative Quantitative Mixed methods Research Methods Questions Data collection Data analysis Interpretation Write-up Validation Figure 1.1 A Framework for Design—The Interconnection of Worldviews, Strategies of Inquiry, and Research Methods 01-Creswell (RD)-45593:01-Creswell (RD)-45593.qxd 6/20/2008 4:36 PM Page 6 6 Preliminary Considerations approaches for their research. -

CCNM17-112 Philosophy of Science Course Description Aim of The

CCNM17-112 Philosophy of Science Course Description Aim of the course Aim of the course: Learning outcome, competences knowledge: broad theoretical knowledge in Philosophy of Science attitude: comprehensive theoretical interest skills: comprehensive methodological knowledge ability to test theoretical questions and for relevant hypotheses Content of the course Topics of the course I. Scientific inquiry: invention and test (Introductory examples for hypotheses, explanations, tests etc.) II. The test of a hypothesis (Experimental and crucial tests. Auxiliary and ad hoc hypotheses.) III. Observation and theory (The Baconian model of science. Novum Organum. Inductive reasoning. Nature and experiment. Observation and experiment. The decuctive-nomological model of explanation. Underdetermination of theories by facts. Observer influence in the various sciences.) IV. Positivism (The British Empiricists. Comte and origins of positivism. Mach and empiriocriticism. The Vienna Circle. The fall of positivism: protocol sentences, justification, demarcation. Problems of induction. Fallibilism.) V. Postpositivism (The cumulative view of XIX. century. Kuhn and scientific revolutions. Paradigms and normal science. Incommensurability. Lakatos and the methodology of scientific research programs. Feyerabend and the problem of development. Evolutionary models of knowledge.) VI. Introduction to sociology of science (Ethnometodology in the lab. The Strong Program in the Sociology of Knowledge. The Empirical Program of Relativism. The social constructivism.) VII. Summary and outlook Learning activities, learning methods: Lectures and interactive discussions Evaluation of outcomes Learning requirements, mode of evaluation, criteria of evaluation: requirements Reliable basic knowledge in the domain of Philosophy of Science mode of evaluation: oral exam criteria of evaluation: Reading list Compulsory reading list F. Bacon: Novum Organum – extracts W. O. Quine: Two Dogmas of Empiricism.