Mining Patterns of the Aspen Leaf Miner, Phyllocnistis Populiella, on Its Host Plant, Populus Tremuloides

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

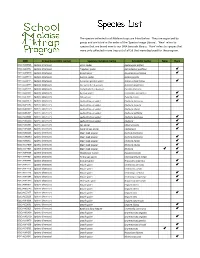

Species List

The species collected in all Malaise traps are listed below. They are organized by group and are listed in the order of the 'Species Image Library'. ‘New’ refers to species that are brand new to our DNA barcode library. 'Rare' refers to species that were only collected in one trap out of all 59 that were deployed for the program. -

Leaf Herbivory by Insects During Summer Reduces Overwinter Browsing by Moose Brian P

Allman et al. BMC Ecol (2018) 18:38 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12898-018-0192-x BMC Ecology RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Leaf herbivory by insects during summer reduces overwinter browsing by moose Brian P. Allman, Knut Kielland and Diane Wagner* Abstract Background: Damage to plants by herbivores potentially afects the quality and quantity of the plant tissue avail- able to other herbivore taxa that utilize the same host plants at a later time. This study addresses the indirect efects of insect herbivores on mammalian browsers, a particularly poorly-understood class of interactions. Working in the Alaskan boreal forest, we investigated the indirect efects of insect damage to Salix interior leaves during the growing season on the consumption of browse by moose during winter, and on quantity and quality of browse production. Results: Treatment with insecticide reduced leaf mining damage by the willow leaf blotch miner, Micrurapteryx sali- cifoliella, and increased both the biomass and proportion of the total production of woody tissue browsed by moose. Salix interior plants with experimentally-reduced insect damage produced signifcantly more stem biomass than controls, but did not difer in stem quality as indicated by nitrogen concentration or protein precipitation capacity, an assay of the protein-binding activity of tannins. Conclusions: Insect herbivory on Salix, including the outbreak herbivore M. salicifoliella, afected the feeding behav- ior of moose. The results demonstrate that even moderate levels of leaf damage by insects can have surprisingly strong impacts on stem production and infuence the foraging behavior of distantly related taxa browsing on woody tissue months after leaves have dropped. -

Leafmining Insects Fact Sheet No

Leafmining Insects Fact Sheet No. 5.548 Insect Series|Trees and Shrubs by W.S. Cranshaw, D.A. Leatherman and J.R. Feucht* Leafminers are insects that have a habit of and/or its droppings (frass). Leaf spotting Quick Facts feeding within leaves or needles, producing fungi cause these areas to collapse, without tunneling injuries. Several kinds of insects any tunneling. • Leafminers are insects have developed this habit, including larvae of that feed within a leaf, moths (Lepidoptera), beetles (Coleoptera), producing large blotches or sawflies (Hymenoptera) and flies (Diptera). Common Leafminers meandering tunnels. Most of these insects feed for their entire of Trees and Shrubs • Although leafminer injuries larval period within the leaf. Some will also Sawfly Leafminers. Most sawflies chew are conspicuous, most pupate within the leaf mine, while others on the surface of leaves, but four species have larvae that cut their way out when full- found in Colorado develop as leafminers of leafminers produce injuries grown to pupate in the soil. woody plants. Adults are small, dark-colored, that have little, if any, effect on Leafminers are sometimes classified by non-stinging wasps that insert eggs into the plant health. the pattern of the mine which they create. newly formed leaves. The developing larvae • Most leafminers have many Serpentine leaf mines wind snake-like across produce large blotch mines in leaves during natural controls that will the leaf gradually widening as the insect late spring. The sawfly leafminers produced a normally provide good control grows. More common are various blotch single generation each year. leaf mines which are generally irregularly Elm leafminer (Kaliofenusa ulmi) is of leafminers. -

Competition As a Structuring Force in Leaf Miner Communities

Oikos 118: 809Á818, 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0706.2008.17397.x, # 2009 The Authors. Journal compilation # 2009 Oikos Subject Editor: Frank Van Veen. Accepted 12 December 2008 Competition as a structuring force in leaf miner communities Ayco J. M. Tack, Otso Ovaskainen, Philip J. Harrison and Tomas Roslin A. J. M. Tack ([email protected]), O. Ovaskainen, P. J. Harrison and T. Roslin, Dept of Biological and Environmental Sciences, Div. of Population Biology, PO Box 65 (Viikinkaari 1), FI-00014 University of Helsinki, Finland. The role of competition in structuring communities of herbivorous insects is still debated. Despite this, few studies have simultaneously investigated the strength of various forms of competition and their effect on community composition. In this study, we examine the extent to which different types of competition will affect the presence and abundance of individual leaf miner species in local communities on oak trees Quercus robur. We first use a laboratory experiment to quantify the strength of intra- and interspecific competition. We then conduct a large-scale field experiment to determine whether competition occurring in one year extends to the next. Finally, we use observational field data to examine the extent to which mechanisms of competition uncovered in the two experiments actually reflect into patterns of co- occurrence in nature. In our experiment, we found direct competition at the leaf-level to be stronger among conspecific than among heterospecific individuals. Indirect competition among conspecifics lowered the survival and weight of larvae of T. ekebladella, both at the branch and the tree-level. In contrast, indirect competition among heterospecifics was only detected in one out of three species pairs examined. -

Widespread Mortality of Trembling Aspen (Populus Tremuloides) Throughout Interior Alaskan Boreal Forests Resulting from a Novel Canker Disease

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Papers in Plant Pathology Plant Pathology Department 2021 Widespread mortality of trembling aspen (Populus tremuloides) throughout interior Alaskan boreal forests resulting from a novel canker disease Roger W. Ruess Loretta M. Winton Gerard C. Adams Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/plantpathpapers Part of the Other Plant Sciences Commons, Plant Biology Commons, and the Plant Pathology Commons This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Plant Pathology Department at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers in Plant Pathology by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. PLOS ONE RESEARCH ARTICLE Widespread mortality of trembling aspen (Populus tremuloides) throughout interior Alaskan boreal forests resulting from a novel canker disease 1 2 3 Roger W. RuessID *, Loretta M. Winton , Gerard C. Adams 1 Institute of Arctic Biology, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, Alaska, United States of America, 2 United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Forest Health Protection, Fairbanks, Alaska, United States of America, 3 Department of Plant Pathology, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, Nebraska, United States of a1111111111 America a1111111111 a1111111111 * [email protected] a1111111111 a1111111111 Abstract Over the past several decades, growth declines and mortality of trembling aspen through- out western Canada and the United States have been linked to drought, often interacting OPEN ACCESS with outbreaks of insects and fungal pathogens, resulting in a ªsudden aspen declineº Citation: Ruess RW, Winton LM, Adams GC (2021) Widespread mortality of trembling aspen throughout much of aspen's range. -

Search: Thu Nov 5 14:40:21 2020Page 1 Of

Search: Thu Nov 5 14:40:21 2020 Page 1 of 180 10 % Athalia cornubiae|[1]|GBSYM1130-12|Hymenoptera|BOLD:AAJ9512 Sciaridae|[2]|CNFNR1642-14|Diptera|BOLD:ACM8049 Sciaridae|[3]|CNPPB684-12|Diptera|BOLD:ACC8493 Sciaridae|[4]|GMGSL144-13|Diptera|BOLD:ACC8327 Sciaridae|[5]|GMOJG309-15|Diptera|BOLD:ACX6391 Tetraneura nigriabdominalis|[6]|ASHMT220-11|Hemiptera|BOLD:AAG3896 Tetraneura ulmi|[7]|CNJAE749-12|Hemiptera|BOLD:AAG3894 Prociphilus caryae|[8]|PHOCT611-11|Hemiptera|BOLD:ABY5255 Prociphilus tessellatus|[9]|TTSOW205-10|Hemiptera|BOLD:AAD7311 Grylloprociphilus imbricator|[10]|RDBA378-06|Hemiptera|BOLD:AAY2624 Subsaltusaphis virginica|[11]|RFBAC272-07|Hemiptera|BOLD:AAH9929 Euceraphis papyrifericola|[12]|BBHCN315-10|Hemiptera|BOLD:AAH2870 Euceraphis|[13]|CNPAI428-13|Hemiptera|BOLD:AAX7972 Calaphis betulaecolens|[14]|ASAHE150-12|Hemiptera|BOLD:AAC3672 Callipterinella calliptera|[15]|RDBA165-05|Hemiptera|BOLD:AAB6094 Periphyllus negundinis|[16]|CNEIB825-12|Hemiptera|BOLD:AAD3938 Sipha elegans|[17]|CNEIF3636-12|Hemiptera|BOLD:AAG1528 Aphididae|[18]|GMGSW027-13|Hemiptera|BOLD:ACD2286 Drepanaphis|[19]|RRMFE3184-15|Hemiptera|BOLD:ABY0945 Drepanaphis|[20]|RDBA009-05|Hemiptera|BOLD:AAH2879 Drepanaphis|[21]|BBHEM601-10|Hemiptera|BOLD:AAX8898 Drepanaphis|[22]|GMGSA077-12|Hemiptera|BOLD:ACA3956 Drepanaphis|[23]|ASAHE012-12|Hemiptera|BOLD:ABY1338 Drepanaphis|[24]|RRSSA5353-15|Hemiptera|BOLD:AAI6141 Drepanaphis parva|[25]|CNSLF196-12|Hemiptera|BOLD:AAX8895 Drepanaphis|[26]|CNPEE1905-14|Hemiptera|BOLD:ACL5395 Drepanaphis acerifoliae|[27]|RFBAG183-11|Hemiptera|BOLD:AAH2868 -

The Lepidoptera Families and Associated Orders of British Columbia

The Lepidoptera Families and Associated Orders of British Columbia The Lepidoptera Families and Associated Orders of British Columbia G.G.E. Scudder and R.A. Cannings March 31, 2007 G.G.E. Scudder and R.A. Cannings Printed 04/25/07 The Lepidoptera Families and Associated Orders of British Columbia 1 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................5 Order MEGALOPTERA (Dobsonflies and Alderflies) (Figs. 1 & 2)...........................................6 Description of Families of MEGALOPTERA .............................................................................6 Family Corydalidae (Dobsonflies or Fishflies) (Fig. 1)................................................................6 Family Sialidae (Alderflies) (Fig. 2)............................................................................................7 Order RAPHIDIOPTERA (Snakeflies) (Figs. 3 & 4) ..................................................................9 Description of Families of RAPHIDIOPTERA ...........................................................................9 Family Inocelliidae (Inocelliid snakeflies) (Fig. 3) ......................................................................9 Family Raphidiidae (Raphidiid snakeflies) (Fig. 4) ...................................................................10 Order NEUROPTERA (Lacewings and Ant-lions) (Figs. 5-16).................................................11 Description of Families of NEUROPTERA ..............................................................................12 -

Aspen Leaf Miner

Aspen Leaf Miner Introduction James Kruse, Forest Entomologist; Aspen Leaf Miner The aspen leaf miner is a transcontinental Angie Ambourn, Biological Science pest of trembling or small tooth aspen. This Technician; and Ken Zogas, Biological Science species, Phyllocnistis populiella, is found across Technician, USDA Forest Service, Alaska Alaska wherever poplar species are found. Region, State and Private Forestry. An outbreak of the aspen leaf miner has been Additional information on this insect can be occurring in Alaska since 2000. Acres of obtained from your local Alaska Cooperative infested aspen identified during annual aerial Extension office, Alaska State Forestry office, surveys have increased from nearly 300,000 or from: acres in 2000, to more than 659,000 acres in 2006. This is the second recorded outbreak Forest Health Protection exceeding 500,000 acres in Alaska (the first State and Private Forestry large recorded outbreak occurred during the Figure 1. Adult moth on aspen leaf bud. USDA Forest Service late-1970s). Infestations of aspen leaf miner 2770 Sherwood Lane, Suite 2A were noted along the Alaska Highway in Juneau, Alaska 99801-8545 Canada as early as the 1950s, and this insect seven eggs per leaf have been found during Phone: (907) 586-8883 also reaches outbreak proportions in the west- outbreaks. When the new larvae hatch, they 3301 “C” Street, Suite 522 ern United States. Outbreaks of aspen leaf bore into the leaf and begin feeding between Anchorage, Alaska 99503 miner rarely occur in eastern North America. the epidermal tissues. Larvae are small, white, Phone: (907) 743-9455 and very flat, reaching about 5 mm long. -

The Face of Alaska: a Look at Land Cover and the Potential Drivers of Change

The Face of Alaska: A look at land cover and the potential drivers of change By Benjamin M. Jones, Research Geographer, Alaska Science Center, U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2008-1161 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DIRK KEMPTHORNE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Mark D. Myers, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2008 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Suggested citation: Jones, B.M., 2008, The Face of Alaska: A look at land cover and the potential drivers of change: U.S. Geological Survey, Open-File Report 2008-1161, 39 p. Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted material contained within this report. ii Contents Abstract................................................................................................................................................................................1 Introduction .........................................................................................................................................................................2 -

Understanding I-Tree: Summary of Programs and Methods David J

United States Department of Agriculture Understanding i-Tree: Summary of Programs and Methods David J. Nowak Forest Service Northern Research Station General Technical Report NRS-200 November 2020 Abstract i-Tree is a suite of computer software tools developed through a collaborative public- private partnership. These tools are designed to assess and value the urban forest resource, understand forest risk, and develop sustainable forest management plans to improve environmental quality and human health. This report provides details about the underlying methods and calculations of these tools, as well their potential limitations. Also discussed are the history of i-Tree, its future goals, and opportunities to facilitate new science and international collaboration. The Author DAVID J. NOWAK is a senior scientist and i-Tree team leader with the USDA Forest Service’s Northern Research Station at Syracuse, New York. The use of trade, firm, or corporation names in this publication is for the information and convenience of the reader. Such use does not constitute an official endorsement or approval by the U.S. Department of Agriculture or the Forest Service of any product or service to the exclusion of others that may be suitable. Manuscript received for publication 13 February 2019 Published by USDA FOREST SERVICE ONE GIFFORD PINCHOT DRIVE MADISON, WI 53726 November 2020 CONTENTS Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................ 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. -

Leaf-Mining Insects and Their Parasitoids in Relation to Plant Succession

Leaf-mining Insects and their Parasitoids in relation to Plant Succession by Hugh Charles Jonathan Godfray A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of London and for the Diploma of Membership of Imperial College. Department of Pure and Applied Biology Imperial College at Silwood Park Silwood Park Ascot Berkshire SL5 7PY November 1982 Abstract In this project, the changes in the community of leaf-miners and their hymenopterous parasites were studied in relation to plant succession. Leaf-miners are insects that spend at least part of their larval existence feeding internally within the leaf. The leaf-miners attacking plants over a specific successional sequence at Silwood Park, Berkshire, U.K. were studied, and the changes in taxonomic composition, host specialization, phenology and absolute abundance were examined in the light of recent theories of plant/insect-herbivore interactions. Similar comparisons were made between the leaf-miners attacking mature and seedling birch. The factors influencing the number of species of miner found on a particular type of plant were investigated by a multiple regression analysis of the leaf-miners of British trees and plant properties such as geographical distribution, taxonomic relatedness to other plants and plant size. The results are compared with similar studies on other groups and a less rigorous treatment of herbaceous plants. A large number of hymenopterous parasites were reared from dipterous leaf-mines on early successional plants. The parasite community structure is compared with the work of R.R.Askew and his associates on the parasites of tree leaf-miners. The Appendices include a key to British birch leaf-miners and notes on the taxonomy and host range of the reared parasites. -

Large Aspen Tortrix Yukon Forest Health — Forest Insect and Disease 11

Large Aspen Tortrix Yukon Forest Health — Forest insect and disease 11 Energy, Mines and Resources Forest Management Branch Introduction The large aspen tortrix (Choristoneura conflictana) is a native defoliator of trembling aspen (Populus tremuloides) throughout aspen’s range in Yukon. Populations periodically reach outbreak levels that persist for up to two years. Outbreak damage results in severe defoliation, branch dieback and gnarly, stunted tree form. Successive years of outbreak can result in extensive tree mortality. Natural factors such as harsh weather, predation or depletion of available food sources usually keep populations in check. Severe large aspen tortrix infestations were first recorded around Teslin Lake in the early 1980s and these outbreaks caused extensive tree mortality. Severe defoliation of trembling aspen was recorded near Braeburn in 1998 and around Haines Junction in 2000 but the populations collapsed in 2001. Since then, large aspen tortrix populations have been in decline, coinciding with the rise in aspen serpentine leafminer (Phyllocnistis populiella) populations. This suggests that the effects of interspecific competition and/or climate change are less advantageous to the tortrix. In Alaska, the ten-year tortix cycle ceased in the early 1980s, coinciding with when mean annual temperatures began to increase. 2 Host Range for Large Aspen Tortrix (Source data: Yukon Government Forest Inventory Data [2008] and U.S. Geological Survey [1999] Digital representation of “Atlas of United States Trees” by Elbert L. Little, Jr. (http://esp.cr.usgs.gov/data/little/) Disclaimer: The data set for historic incidence is likely incomplete and only extends from 1994–2008. Endemic or outbreak populations may have occurred or may currently exist in non-mapped locations within the host range.