Pioneers of Evolution from Thales to Huxley. with an Intermediate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ferguson Jenkins: Biography from Answers.Com 4/17/10 6:38 PM

Ferguson Jenkins: Biography from Answers.com 4/17/10 6:38 PM Ferguson Jenkins Britannica Concise Encyclopedia: Ferguson Jenkins Fergie Jenkins (born Dec. 13, 1943, Chatham, Ont., Can.) Canadian-born U.S. baseball pitcher. In high school Jenkins excelled in amateur baseball, basketball, and hockey. He began his major league career with the Philadelphia Phillies in the early 1960s, before playing for the Chicago Cubs, the Texas Rangers, and the Boston Red Sox, winning at least 20 games in each of six consecutive seasons (1967 – 72) and setting several season records. He was awarded the Cy Young award in 1971 for his 24 – 13 won-lost record and 2.77 earned run average. For more information on Fergie Jenkins, visit Britannica.com. Black Biography: Fergie Jenkins baseball player Personal Information Born Ferguson Arthur Jenkins on December 13, 1943, in Chatham, Ontario, Canada; married Kathy Williams, 1965 (divorced); married Maryanne (died 1991); married Lydia Farrington, 1993; children: Kelly, Delores, Kimberly, Raymond (stepson), Samantha (died 1993). Memberships: Major League Baseball Players Alumni Association Career Philadelphia Phillies (National League), professional baseball player, 1965-66; Chicago Cubs (National League), professional baseball player, 1966-73, 1982-83; Texas Rangers (American League), professional baseball player, 1974-75, 1978-81; Boston Red Sox (American League), professional baseball player, 1976-77. Team Canada, pitching coach for Pan-Am Games, 1987; Texas Rangers (Oklahoma City 89ers minor league team), pitching coach, 1988-89; Cincinnati Reds, roving minor league coach, 1992-93; Chicago Cubs, minor league coach, 1995-96; Canadian Baseball League, commissioner, 2003-. http://www.answers.com/topic/ferguson-jenkins?&print=true Page 1 of 12 Ferguson Jenkins: Biography from Answers.com 4/17/10 6:38 PM Life's Work "Pitchers are a breed apart...," wrote Eliot Asinof in a Time biography of pitching great Fergie Jenkins. -

2015 Preseason College Baseball Guide (PDF)

BASEBALL 2015 A supplement to the NCAA Baseball Rules • Prepared by the editors of Referee Umpires May Conference for Catch/No Catch Decisions n expansion of the “Getting the ACall Right” principle was ap- proved by the NCAA Baseball Rules Committee during its annual meet- ing. Umpires will now be allowed to conduct a conference to change a call of “catch” to “no catch” and a call of “no catch” to “catch.” The committee approved the change in an effort to modernize the game, and to get an incorrect call changed to what should have been the correct call. Under the new rule, if a play to the outfield originally is called a catch but is overturned by umpire conference or through video evidence, the play will be declared dead and the batter will be placed at first base. Each runner will be advanced one base from the position occupied at the time of the pitch. If the play is overturned in foul territory, it will be ruled a foul ball and all runners will return to the Starting this season, umpires (from left) Billy VanRaaphorst, Los Angeles; Mike Conlin, Lansing, base they occupied at the time of the Mich.; Jeff Head, Birmingham Ala.; Doug Williams, College Station, Texas; and Scott Erby, pitch. Nashville, Tenn., may conduct a conference to ensure a correct call on a catch/no catch situation. On plays to the outfield that are overturned from “no catch” and tournament games currently used to decide if an apparent home to “catch,” all action prior to the to allow the umpires to conference run is fair or foul; deciding whether ball being declared dead will be and reverse a call of “catch” to “no a batted ball left the playing field disallowed. -

Right Off the Bat

Right off the Bat By William F. Kirk Right Off the Bat JOHN BOURBON, PITCHER THEY tell me that Matty can pitch like a fiend, But many long years before Matty was weaned I was pitching to players, and good players, too, Mike Kelley and Rusie and all the old crew. Red Sockalexis, the Indian star, Breitenstein, Clancy, McGill and McGarr. Matty a pitcher? Well, yes, he may be, But where in the world is a pitcher like me? My name is John Bourbon, I’m old, and yet young; I cannot keep track of the victims I’ve stung. I’ve studied their weaknesses, humored their whims, Muddled their eyesight and weakened their limbs, Bloated their faces and dammed up their veins, Rusted their joints and beclouded their brains. Matty a pitcher? Well, yes, he may be, But where in the world is a pitcher like me? I have pitched to the stars of our national game, I have pitched them to ruin and pitched them to shame. They laughed when they faced me, so proud of their strength, Not knowing, poor fools, I would get them at length. I have pitched men off pinnacles scaled in long years. I have pitched those they loved into oceans of tears. Matty a pitcher? Well, yes, he may be, But where in the world is a pitcher like me? SUNDAY BASEBALL THE East Side Slashers were playing the Terrors, Piling up hits, assists and errors; Far from their stuffy tenement homes That cluster thicker than honeycombs, They ran the bases like busy bees, Fanned by the Hudson’s cooling breeze. -

The Daily Egyptian, June 19, 1987

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC June 1987 Daily Egyptian 1987 6-19-1987 The aiD ly Egyptian, June 19, 1987 Daily Egyptian Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/de_June1987 Volume 73, Issue 157 Recommended Citation , . "The aiD ly Egyptian, June 19, 1987." (Jun 1987). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Daily Egyptian 1987 at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in June 1987 by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Daily Egyptian Southern Illinois University at C arbondale Friday, June 19. 1987, Vol. 73, No. 157 20 Pages Tuition boost hinges on plan !o raise taxes By Jacke Hampton Staff Writer " Hopefully some type of tax increase will be approved so Students coold face another the trustees won 't have to tuition increase if Gov. James consider that," she said. R. Thompson's tax hike plan "They've worked very hard to fails, a spokesman in the hold down tuition costs and chancellor's office said keep SIU's the lowest in Thursday. lliinois.·' "No one is disco'lllting that Pettit didn't mention tax or possibili ty, " said Ca therine tuition hikes specifically when Walsh, assistant to (''hancell<", he testified before the ap Lawrence K. Pettit. propriations committee "The $1 million increase Wednesday, cut he said approved Wednesday by the present-level funding woold appropriations committee is slow growth in several areas. actually level funding. It now Under Thompson's original goes to the House where it can proposal, sru wa. -

Brown Gives State of Student Union Address

---- -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------~ THE The Independent Newspaper Serving Notre Dame and Saint Mary's OLUME 42: ISSUE 23 ' THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER27, 2007 NDSMCOBSERVER.COM Brown gives State of Student Union address Speech urges all senators to raise bar of Senate supports Notre progress, focus working on projects at hand Dame divestment initiative ordinance that has been a By KAITLYNN RIELY focal point for student govern By KAITLYNN RIELY Assistant News Editor ment since the end of July. Assistant News Editor The ordinance, as it was Student body president Liz originally written, would have Student Senate unanimously passed Brown invoked her campaign required residents of boarding a resolution Wednesday commending slogan - "raising the bar, houses - defined as resi the University for divesting from redefining the standards" - dences where more than two companies that support the Sudanese in her second State of the unrelated people reside - to government as human rights viola Student Union address register for a permit before tions continue in the country's Darfur Wednesday, urging senators to hosting a gathering where 25 region. not become complacent with or more people would have The resolution, presented by Social the progress they have access to alcohol. Concerns chair Karen Koski and already made and to keep Brown, as well as vice presi Lyons senator Kelly Kanavy, urges working on initiatives. dent Maris Braun, began Notre Dame's Investment Office to "While our progress thus far meeting with the Common continue divesting from companies demonstrates our ability to Council and other South Bend that do business with the government effectively respond to student and University representatives' of Sudan. -

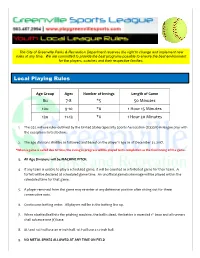

Local Playing Rules

The City of Greenville Parks & Recreation Department reserves the right to change and implement new rules at any time. We are committed to provide the best programs possible to ensure the best environment for the players, coaches and their respective families. Local Playing Rules Age Group Ages Number of Innings Length of Game 8u 7-8 *5 50 Minutes 10u 9-10 *6 1 Hour 15 Minutes 13u 11-13 *6 1 Hour 20 Minutes 1. The GSL will use rules outlined by the United States Specialty Sports Association (USSSA) in league play with the exceptions listed below. 2. The age divisions shall be as followed and based on the player’s age as of December 31, 2017. *When a game is called due to time, the inning in progress will be played to its completion as the final inning of the game. 3. All Age Divisions will be MACHINE PITCH. 4. If any team is unable to play a scheduled game, it will be counted as a forfeited game for their team. A forfeit will be declared at scheduled game time. An unofficial game/scrimmage will be played within the scheduled time for that game. 5. A player removed from the game may re-enter at any defensive position after sitting out for three consecutive outs. 6. Continuous batting order. All players will be in the batting line up. 7. When a batted ball hits the pitching machine, the ball is dead, the batter is awarded 1st base and all runners shall advance one (1) base. 8. 8U and 10U will use an 11-inch ball. -

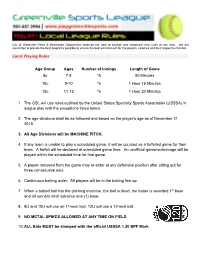

Local Playing Rules Age Group Ages Number of Innings Length of Game 8U 7-8 *5 50 Minutes 10U 9-10 *6 1 Hour 15 Minutes 12U

City of Greenville Parks & Recreation Department reserves the right to change and implement new rules at any time. We are committed to provide the best programs possible to ensure the best environment for the players, coaches and their respective families Local Playing Rules Age Group Ages Number of Innings Length of Game 8u 7-8 *5 50 Minutes 10u 9-10 *6 1 Hour 15 Minutes 12u 11-12 *6 1 Hour 20 Minutes 1. The GSL will use rules outlined by the United States Specialty Sports Association (USSSA) in league play with the exceptions listed below. 2. The age divisions shall be as followed and based on the player’s age as of December 31, 2018. 3. All Age Divisions will be MACHINE PITCH. 4. If any team is unable to play a scheduled game, it will be counted as a forfeited game for their team. A forfeit will be declared at scheduled game time. An unofficial game/scrimmage will be played within the scheduled time for that game. 5. A player removed from the game may re-enter at any defensive position after sitting out for three consecutive outs. 6. Continuous batting order. All players will be in the batting line up. 7. When a batted ball hits the pitching machine, the ball is dead, the batter is awarded 1st base and all runners shall advance one (1) base. 8. 8U and 10U will use an 11-inch ball. 12U will use a 12-inch ball. 9. NO METAL SPIKES ALLOWED AT ANY TIME ON FIELD 10.ALL Bats MUST be stamped with the official USSSA 1.20 BPF Mark Playing Field 1. -

LCSA - 2021 Rules 8U House League

LCSA - 2021 Rules 8U House League 1 Standard USA Softball (formally ASA Softball) rules will be followed with the following exceptions which are described below. 2 All players in good standing will be listed in the batting line up and will bat in that order. Good standing shall mean faithful attendance at practices and games unless the manager excuses the absence in advance. 3 No player in good standing will sit out more than two (2) innings per game. "Sitting Out" is defined as not participating when your team is in the field. 4 All players bat in order whether playing in the field or not. Any player who must leave the game early will NOT be called out each time she would be at bat. 5 If a player cannot bat because of injury, she will NOT be called out each time she is up to bat. She can re-enter the game. 6 Any player NOT at the field by the conclusion of the pre-game plate meeting – will NOT be included in the line-up. Upon arriving at the field she can immediately be inserted at the end of the lineup and can take a position on the field. 7 Ten (10) players may play in the field at one time, but no less than six (6) are required to start and continue play in a game. To avoid a forfeit, one team may lend player(s) to the other team to get them to the minimum of 6 players for the entirety of the game (offense & defense), at which point the game is official (no longer a forfeit situation). -

LCSA - 2017 Rules 8U House League

LCSA - 2017 Rules 8U House League 1 Standard USA Softball (formally ASA Softball) rules will be followed with the following exceptions which are described below. 2 All players in good standing will be listed in the batting line up and will bat in that order. Good standing shall mean faithful attendance at practices and games unless the manager excuses the absence in advance. 3 No player in good standing will sit out more than two (2) innings per game. "Sitting Out" is defined as not participating when your team is in the field. 4 All players bat in order whether playing in the field or not. Any player who must leave the game early will NOT be called out each time she would be at bat. 5 If a player cannot bat because of injury, she will NOT be called out each time she is up to bat. She can re-enter the game. 6 Any player NOT at the field by the conclusion of the pre-game plate meeting – will NOT be included in the line-up. Upon arriving at the field she can immediately be inserted at the end of the lineup and can take a position on the field. 7 Ten (10) players may play in the field at one time, but no less than six (6) are required to start and continue play in a game. Other team may lend players, at which point the game is official (no longer a forfeit situation). 8 A maximum of six (6) players can be positioned in the infield prior to the pitch. -

Reagan Lobbies Congress, Public for Role in Gulf

RkHK Students Field trip; Tangible' history at museum / page 3 battle police In 8. Korea / page 7 Champs: Lakers beat Celts for title / page 11 iHaufhriitrr Hrralii ) nr,hf; Monday, June 15,1flS7 30 C«n1s ■All Reagan lobbies J Congress, public for role in Gulf U m . WASHINGTON (AP) - President Reagan, turned down in his bid for allied ■ The commandgrt of th« USS military help in the Persian Gulf, is •tm. taking his case for a strengthened U.S. Stark failad to taka proper defan* role in the troubled waterway to alve meaaurea before an Iraqi’ N Congress and the American people. warplane hit the ahip with mlaalles, / /> White House officials, speaking Sun according to a congreaalonal J- I? day on condition they not be identified, report. said Reagan Is expected to touch on the tense situation In the gulf In a report to ■ Aa the Reagan administration the^ nation tonight on the Venice prepares to explain how It will econofiilc summit. defend reflagged Kuwaiti oil In addition to the nationally broadcast tankers, senior Democratic law speech from the bval Office, Reagan makers urge the White House to will deliver a report on security of U.S. ships in the gulf to Congress early this delay or cancel plans to risk week. Aides said the bulk of the report American lives and prestige In the will be stamped secret, but portions Persian Quit. probably will be public. The administration plans to fly the — Sforfes on page 5 U.S. flag on 11 Kuwaiti tankers and escort them with U.S. -

TOP GUN COACH PITCH RULES 8 & Girls Division

TOP GUN COACH PITCH RULES 8 & Girls Division Revised December 10, 2019 AGE CUT OFF A. Age 8 & under. Cut off date is January 1st. Player may not turn 9 before January 1st. Please have Birth Certificates or copies available if needed. NATIONAL FEDERATION RULES B. National Federation Rules Apply with the following TOP GUN EXCEPTIONS SOFTBALL USED C. High School Federation Rules apply. We will use the 11” ball. RECOMMENDED FENCE DISTANCE D. The recommended fence distance is from 140 feet to 200 feet. BAT RESTRICTIONS E. High School Federation rules apply. REGULATION GAME AND TIME LIMIT F. A regulation game will be SIX (6) innings. G. Time limit will be one (1) hour. On all games including Bracket Play RUN RULE H. Top Gun will use the 12, 10, 8 run rule in all tournament play. If one team is 12, 10, or 8 runs ahead after 3, 4, or 5 innings, or after 2 ½ , 3 ½, or 4 ½ innings the home team is ahead by 12, 10, or 8 runs or more, then the team with the lead of runs is declared the winner. BASE PATH I. Base paths will be 60 feet. PITCHING J. Pitching rubber or plate will be set at 35 feet. K. Pitchers circle will be 8 feet radius from the pitcher plate. L. The coach/pitcher must pitch from the pitcher plate or behind the pitcher plate. M. Pitching distance will be 35 feet for the minimum and 40 feet as the maximum. N. Player pitcher must have one foot inside pitching circle and must be even with or behind the 35' pitching rubber at the batters contact, providing the batter is not bunting. -

Keeping Peace in P'slope

Aug. 18–24, 2017 Including Brooklyn Courier, Carroll Gardens-Cobble Hill Courier, Brooklyn Heights Courier, & Williamsburg Courier FREE ALSO SERVING PROSPECT HEIGHTS, WINDSOR TERRACE, KENSINGTON, AND GOWANUS COUNTING THE CASH City withholding fi nancial details on armory deal, lawmakers say BY COLIN MIXSON nities to include more afford- housing for us?” State Sen. oper BFC Partners are seek- blast the project’s affordable Talk about being short- able housing in the scheme Jesse Hamilton (D–Crown ing public approval to build housing — which prices only changed. that calls for 50-plus luxury Heights) said at a public meet- dozens of below-market-rate 18 of more than 330 rental units The city refuses to give lo- condos, according to a state ing about the project on Aug. rental units and a community at rates within the means of cal lawmakers fi nancial infor- senator. 2. “Because if they show it to recreation center at the his- community members — as se- mation on the redevelopment “Mr. Mayor, why aren’t us, we can have 100-percent af- toric military structure on verely lacking. plan for the publicly owned you giving us the fi nancials fordable. But they don’t want Bedford Avenue between Pres- And the state senator also Bedford-Union Armory, po- for a project that is our land, 100-percent affordable.” ident and Union streets. doubts that below-market-rate tentially obstructing opportu- our money … supposedly for The city and private devel- But neighbors continue to Continued on page 25 Keeping peace in P’Slope Locals rally in response to fatal Charlottesville violence BY COLIN MIXSON They took it to the extrem- ists.