The Ground Observer Corps Public Relations and the Cold War in the 1950S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

26Th AIR DIVISION

26th AIR DIVISION MISSION LINEAGE 26th Air Defense Division established, 21 Oct 1948 Activated, 16 Nov 1948 Redesignated 26th Air Division (Defense), 20 Jun 1949 Inactivated, 1 Feb 1952 Organized, 1 Feb 1952 Redesignated 26th Air Division (SAGE), 8 Aug 1958 Redesignated 26th Air Division, 1 Apr 1966 Inactivated, 30 Sep 1969 Activated, 19 Nov 1969 Inactivated, 30 Sep 1990 STATIONS Mitchel AFB, NY, 16 Nov 1948 Mitchel AFB Sub Base #3, Roslyn, NY, 18 Apr 1949-1 Feb 1952 Mitchel AFB Sub Base #3, Roslyn (later, Roslyn AFS), NY, 1 Feb 1952 Syracuse AFS, NY, 15 Aug 1958 Hancock Field, NY, 14 Feb 1959 Stewart AFB, NY, 15 Jun 1964 Adair AFS, OR, 1 Apr 1966-30 Sep 1969 Luke AFB, AZ, 19 Nov 1969 March AFB, CA, 31 Aug 1983-1 Jul 1987 ASSIGNMENTS First Air Force, 16 Nov 1948 Air Defense Command, 1 Apr 1949 First Air Force, 16 Nov 1949 Eastern Air Defense Force, 1 Sep 1950-1 Feb 1952 Eastern Air Defense Force, 1 Feb 1952 Air Defense Command, 1 Aug 1959 Fourth Air Force, 1 Apr 1966-30 Sep 1969 Tenth Air Force, 19 Nov 1969 Aerospace Defense Command, 1 Dec 1969 Tactical Air Command, 1 Oct 1979 First Air Force, 6 Dec 1985-30 Sep 1990 ATTACHMENTS Eastern Air Defense Force, 17 Nov 1949-31 Aug 1950 COMMANDERS Unkn (manned at paper unit strength), 16 Nov 1948-31 Mar 1949 Col Ernest H. Beverly, 1 Apr 1949 BG Russell J. Minty, Nov 1949 Col Hanlon H. Van Auken, 1953 BG James W. McCauley, 1 Apr 1953 BG Thayer S. -

United States Air Force and Its Antecedents Published and Printed Unit Histories

UNITED STATES AIR FORCE AND ITS ANTECEDENTS PUBLISHED AND PRINTED UNIT HISTORIES A BIBLIOGRAPHY EXPANDED & REVISED EDITION compiled by James T. Controvich January 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTERS User's Guide................................................................................................................................1 I. Named Commands .......................................................................................................................4 II. Numbered Air Forces ................................................................................................................ 20 III. Numbered Commands .............................................................................................................. 41 IV. Air Divisions ............................................................................................................................. 45 V. Wings ........................................................................................................................................ 49 VI. Groups ..................................................................................................................................... 69 VII. Squadrons..............................................................................................................................122 VIII. Aviation Engineers................................................................................................................ 179 IX. Womens Army Corps............................................................................................................ -

ADC and Antibomber Defense, 1946-1972

Obtained and posted by AltGov2: www.altgov2.org ADC HISTORICAL STUDY NO. 39 THE AEROSPACE DEFENSE COMMAND AND ANTIBOMBER DEFENSE 194& -1972 ADCHO 73-8-17 FOREWORD" The resources made available to the Aerospace Defense Command (and the predecessor Air Defense Command) for defense against the manned bomber have ebbed and flowed with changes in national military policy. It is often difficult to outline the shape of national policy, however, in a dynamic society like that of the United States. Who makes national policy? Nobody, really. The armed forces make recommenda tions, but these are rarely accepted, in total, by the political administration that makes the final pbrposals to Congress. The changes introduced at the top executive level are variously motivated. The world political climate must be considered, as must various political realities within the country. Cost is always a factor and a determination must be made as to the allocation of funds for defense as opposed to allocations to other government concerns. The personalities, prejudices and predilections of the men who occupy high political office invariably affect proposals to Congress. The disposition of these proposals, of course, is in the hands of Congress. While the executive branch of the government is pushect' and pulled in various directions, Congress is probably subject to heavier pressures. Here, again, the nature of the men who occupy responsible positions within the Congress often affect the decisions of Congress. ·National policy, then, is the product of many minds and is shaped by many diverse interests. The present work is a recapitulation and summarization of three earlier monographs on this subject covering the periods 1946-1950 (ADC Historical Study No. -

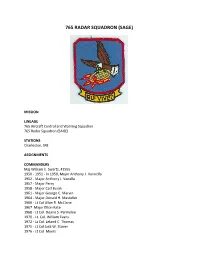

765 Radar Squadron (Sage)

765 RADAR SQUADRON (SAGE) MISSION LINEAGE 765 Aircraft Control and Warning Squadron 765 Radar Squadron (SAGE) STATIONS Charleston, ME ASSIGNMENTS COMMANDERS Maj William E. Swartz, #1955 1950 - 1951 - In 1950, Major Anthony J. Vannella 1952 - Major Anthony J. Vanella 1957 - Major Perry 1958 - Major Carl Burak 1961 - Major George C. Marvin 1964 - Major Donald H. Masteller 1966 - Lt Col Allan R. McClane 1967 Major Elton Kate 1968 - Lt Col. Deane S. Parmelee 1970 - Lt. Col. William Evans 1972 - Lt Col. Leland C. Thomas 1975 - Lt Col Jack W. Stover 1976 - Lt Col. Myers 1979 - Major Stymeist HONORS Service Streamers Campaign Streamers Armed Forces Expeditionary Streamers Decorations EMBLEM EMBLEM SIGNIFICANCE MOTTO NICKNAME OPERATIONS MAINE P-65/Z-65 - Charleston The 765th AC&W Squadron brought Charleston AFS to life in April 1952 and assumed coverage that had been provided by a Lashup site at Dow AFB (L-l). The site initially had AN/FPS-3 and 5 radars. In 1957 an AN/FPS-6 replaced the AN/FPS-5 height-finder radar. Another height-finder radar came in 1958 along with an AN/FPS-20 search radar that replaced the AN/FPS-3. During 1959 Charleston joined the SAGE system. In 1963 the site became the first in the nation to receive an AN/FPS-27. This radar subsequently was upgraded to become an ANFPS-27A. The 765th was deactivated in September 1979. The 765th AC&W Squadron brought Charleston AFS to life in April 1952 and assumed coverage that had been provided by a Lashup site at Dow AFB (L-l). -

16004491.Pdf

-'DEFENSE ATOMIC SUPPORT AGENCY Sandia Base, Albuquerque, New Mexico ,L/PE - 175 Hi%&UhIiT~ SAIdDIA BASE ALBu2umxJE, la$ mXIc0 7 October 1960 This is to cert!e tlmt during the TDY period at this station, Govement Guarters were available and Goverrrment Fessing facilities were not availzble for the following mmoers of I%Ki: Colonel &w, Og~arHe USA Pi3 jor Andm~n,Qaude T. USAF Lt. Colonel fsderacn, George R. USAF Doctor lrndMvrsj could Re Doctor Acdrem, Howard L. USPIG Colonel ksMlla stephen G. USA Colonel Ayars, Laurence S. USAF Lt. Colonel Bec~ew~ki,Zbignie~ J. USAF Lt. Colonel BaMinp, George S., Jr. USAF bjor Barlow, Lundie I:., Jr. UMG Ckmzzder m, h3.llian E. USPHS Ujor Gentley, Jack C. UskF Colonel Sess, Ceroge C. , WAF Docto2 Eethard, 2. F. Lt. c=Jlonel Eayer, David H., USfiF hejor Bittick, Paul, Jr. USAF COlOIle3. Forah, hUlhm N. USAF &;tail? Boulerman, :!alter I!. USAF Comander hwers, Jesse L. USN Cz?trin Brovm, Benjamin H, USAF Ca?tain Bunstock, lrKulam H. USAF Colonel Campbell, lkul A. USAF Colonel Caples, Joseph T. USA Colonel. Collins, CleM J. USA rmctor Collins, Vincent P. X. Colonel c0nner#, Joseph A. USAF Cx:kain ktis, Sidney H. USAF Lt. Colonel Dauer, hxmll USA Colonel kvis, Paul w, USAF Captsir: Deranian, Paul UShT Loctcir Dllle, J. Robert Captain Duffher, Gerald J. USN hctor Duguidp Xobert H. kptain arly, klarren L. use Ca?,kin Endera, Iamnce J. USAF Colonel hspey, James G., Jr. USAF’ & . Farber, Sheldon USNR Caifain Farmer, C. D. USAF Ivajor Fltzpatrick, Jack C. USA Colonel FYxdtt, Nchard s. -

84Th FLYING TRAINING SQUADRON

84th FLYING TRAINING SQUADRON MISSION LINEAGE 84th Pursuit Squadron (Interceptor) constituted, 13 Jan 1942 Activated, 9 Feb 1942 Redesignated 84th Pursuit Squadron (Interceptor) (Twin-Engine), 22 Apr 1942 Redesignated 84th Fighter Squadron (Twin-Engine), 15 May 1942 Redesignated 84th Fighter Squadron, 1 Mar 1943 Redesignated 84th Fighter Squadron, Single-Engine, 21 Aug 1944 Inactivated, 18 Oct 1945 Activated, 20 Aug 1946 Redesignated 84th Fighter Squadron, Jet, 24 Sep 1948 Redesignated 84th Fighter Interceptor Squadron, 20 Jan 1950 Redesignated 84th Fighter Interceptor Training Squadron, 1 Jul 1981 Inactivated, 27 Feb 1987 Redesignated 84th Flying Training Squadron, 9 Feb 1990 Activated, 2 Apr 1990 Inactivated, 1 Oct 1992 Activated, 1 Oct 1998 STATIONS Baer Field, IN, 9 Feb 1942 Muroc, CA, 30 Apr 1942 Oakland, CA, 11 May 1942 Hamilton Field, CA, 4-10 Nov 1942 Goxhill, England, 1 Dec 1942 Duxford, England, 1 Apr 1943-11 Oct 1945 Camp Kilmer, NJ, 16-18 Oct 1945 Straubing, Germany, 20 Aug 1946-25 Jun 1947 Mitchel Field, NY, 25 Jun 1947 Hamilton AFB, CA, 24 Nov 1948 Castle AFB, CA, 1 Sep 1973-27 Feb 1987 Laughlin AFB, TX, 2 Apr 1990-1 Oct 1992 Laughlin AFB, TX, 1 Oct 1998 ASSIGNMENTS 78th Pursuit (later, 78th Fighter) Group, 9 Feb 1942-18 Oct 1945 78th Fighter (later, 78th Fighter Interceptor) Group, 20 Aug 1946 4702nd Defense Wing, 6 Feb 1952 28th Air Division, 7 Nov 1952 566th Air Defense Group, 16 Feb 1953 78th Fighter Group, 18 Aug 1955 78th Fighter Wing, 1 Feb 1961 1st Fighter Wing, 31 Dec 1969 26th Air Division, 1 Oct 1970-27 Feb 1987 47th Flying Training Wing, 2 Apr 1990 47th Operations Group, 15 Dec 1991-1 Oct 1992 47th Operations Group, 1 Oct 1998 WEAPON SYSTEMS P-38, 1942-1943 P-47, 1943-1944 P-51, 1944-1945 F-51, 1949-1951 F-84, 1949-1951 F-89, 1951-1952 F-86, 1952-1958 F-89, 1958-1959 F-101, 1959-1968 F-106, 1968-1981 F-106A F-106B T-33, 1981-1987 T-37, 1990-1992 P-47C P-47D P-51B P-51D P-51K F-84D F-89B F-94B P-38E P-38F F-101B F-101F COMMANDERS Maj Eugene P. -

551St ELECTRONIC SYSTEMS WING

551st ELECTRONIC SYSTEMS WING MISSION The 551st Electronic Systems Wing, a unit of the Air Force Electronic Systems Center at Hanscom AFB, MA, delivers superior capabilities from assigned programs: AWACS, Joint STARS, E-10A/MP- RTIP, Mission Planning, and Weather providing strategic support to ongoing operations, identifying capability information integration opportunities and equipping the war fighter with the technical edge needed to meet comBatant mission requirements. The wing's mission is execute a $12 Billion in approved program funds to develop, provide, sustain and evolve integrated current and future surveillance, Battle planning, Battle management, and battle execution capabilities to meet United States and Allied and Coalition requirements By teaming with the war fighter, industry, and enterprise partners. The mission is accomplished from the resources of four Electronic Systems Groups (ELSG) and one direct reporting division. LINEAGE 51st Transport Wing Established, 30 May 1942 Activated, 1 Jun 1942 Redesignated 51st Troop Carrier Wing, 4 Jul 1942 Inactivated, 5 Jan 1948 Disestablished, 15 Jun 1983 551st AirBorne Early Warning and Control Wing, established, 11 Oct 1954 Activated, 18 Dec 1954 Inactivated, 31 Dec 1969 51st Troop Carrier Wing and 551st AirBorne Early Warning and Control Wing reestablished, consolidated and redesignated 551st AirBorne Warning and Control Wing, 31 Jul 1985 Battle Management Systems Wing, established, 23 Nov 2004 Activated, 17 Dec 2004 551st AirBorne Warning and Control Wing and Battle Management -

Another Look of the Missile Squadrons

Air Force Missileers The Quarterly Newsletter of the Association of Air Force Missileers Volume 25, Number 3 “Advocates for Missileers” September 2017 Sentinel Warriors 1 Cheyenne in 2018, Our 25th Anniversary 2 South Dakota Titan I 3 Missileer Leaders 4 Missile Models on Display 9 Minuteman Missile NHS News 10 New Atlas Models, Missile Squadron Update 11 Minuteman Key Return 16 A Word from AAFM, Letters 17 New Members Page, Taps for Missileers 18 Donations Pages 19 Registration for 2018 National Meeting Inside Back Cover Reunions and Meetings Back Cover The Mission of the Association of Air Force Missileers - - Preserving the Heritage of Air Force Missiles and the people involved with them - Recognizing Outstanding Missileers - Keeping Missileers Informed - Encouraging Meetings and Reunions - Providing a Central Point of Contact for Missileers Association of Air Force Missileers Membership Categories Membership Application Annual ($20) ____ Active Duty/Student ($5) ____ Complete and mail to: Three Years ($50) ____ Active Duty/Student ($14) ____ AAFM PO Box 5693 Lifetime ($300) ____ (Payable in up to 12 installments) Breckenridge, CO 80424 Awarded Missile Badge - Yes _____ No _____ or log on to www.afmissileers.org Member Number _________________ Name Home Phone Address E-mail City State Zip Code Rank/Grade Active Retired Duty Reserve or Can AAFM release this information-only to members and missile organizations? Yes ____ No ___ Nat Guard Discharged/ Separated Civilian Signature Summary of your missile experience - used in the AAFM database -

148 Fighter Squadron

148 FIGHTER SQUADRON MISSION LINEAGE 347 Fighter Squadron activated by special authority prior to constitution, 2 Oct 1942 Constituted, 2 Oct 1942 Inactivated, 7 Nov 1945 Redesignated 148 Fighter Squadron and allotted to ANG, 24 May 1946 Activated 27 Feb 1947 Redesignated 148 Fighter-Bomber Squadron, Dec 1952 Redesignated 148 Fighter Interceptor Squadron, Jul 1955 Inactivated, 1956 Activated as 148 Tactical Fighter Training Squadron, 15 Oct 1985 Redesignated 148 Fighter Squadron, 15 Mar 1992 STATIONS Bushey Hall, England, 1 Oct 1942 Snailwell, England, 4 Oct 1942 (ground echelon, which was formed in US, was at Harding Field, La, until 2 Nov 1942) Kings Cliffe, England, 8 Dec 1942-4 Jan 1943 Casablanca, French Morocco, 20 Nov 1942 Oujda, French Morocco, 6 Jan 1943 La Senia, Algeria, 12 Feb 1943 Orleansville, Algeria, 9 Mar 1943 Le Sers, Tunisia, 21 Apr 1943 Djidjelli, Algeria, 14 May 1943 Rerhaia, Algeria, 18 Nov 1943 Corsica, 6 Dec 1943 (detachment operated from Capodichino, Italy, 10 Feb-Mar 1944) Sardinia, 19 Ju1 1944 Tarquinia, Italy, 15 Sep 1944 Pisa, Italy, 2 Dec 1944-14 Jul 1945 Seymour Johnson Field, NC, 25 Aug-7 Nov 1945 Reading, PA, 1947-1956 Tucson, AZ, 1985 ASSIGNMENTS 350 Fighter Group, 1 Oct 1942-7 Nov 1945 4710 Defense Wing 6 Feb 52 162 Operations Group WEAPON SYSTEMS Mission Aircraft P-39, 1942 P-400, 1942 P-38, 1943 P-47, 1944 P-47, 1947 A-26 F-51 F-84, May 1951 F-94, 1951 F-16 Support Aircraft C-47, 1947 AT-6, 1947 COMMANDERS Maj Russel R. Ogan LTC Richard B. -

Almanac ■ Records, Trophies, and Competitions

USAFAlmanac ■ Records, Trophies, and Competitions Absolute Aviation World Records The desirability of a standard procedure nations and certifies national records as flying machines. Several of these records to certify air records was recognized early world records. are more than 10 years old. The NAA in the history of powered flight. In 1905, Since 1922, the National Aeronautic notes that, “since the performance of representatives of Belgium, Germany, the Association (NAA), based in Arlington, many government-backed airplanes . is US, Great Britain, France, Spain, Italy, Va., has been the US representative to wrapped in a blanket of national security, and Switzerland met in Paris to form the the FAI. The NAA supervises all attempts the breaking of some of these records Fédération Aéronautique Internationale at world and world-class records in the will depend as much on political consider- (FAI), the world body of national aero- United States. ations as technical ones.” nautic sporting interests. The FAI today Absolute world records are the supreme comprises the national aero clubs of 77 achievements of all the records open to Record Pilot(s) Aircraft Route/Location Date(s) Speed around the world, ......Richard Rutan and ................ Voyager experimental ...... Edwards AFB, Calif., ........ December 14–23, 1986 nonstop, nonrefueled: Jeana Yeager aircraft to Edwards AFB, Calif. 115.65 mph (186.11 kph) Great circle distance............Richard Rutan and ................ Voyager experimental ...... Edwards AFB, Calif., ........ December 14–23, 1986 without landing: Jeana Yeager aircraft to Edwards AFB, Calif. 24,986.727 miles (40,212.139 kilometers) Distance in a closed ............Richard Rutan and ................ Voyager experimental ...... Edwards AFB, Calif., ....... -

82Nd FIGHTER GROUP (AIR DEFENSE)

82nd FIGHTER GROUP (AIR DEFENSE) MISSION LINEAGE 82nd Pursuit Group (Interceptor) constituted, 13 Jan 1942 Activated, 9 Feb 1942 Redesignated 82nd Fighter Group, May 1942 Inactivated, 9 Sep 1945 Activated, 12 Apr 1947 Inactivated, 2 Oct 1949 Redesignated 82nd Fighter Group (Air Defense) Activated, 18 Aug 1955 STATIONS Harding Field, LA, 9 Feb 1942 Muroc, CA, 30 Apr 1942 Los Angeles, CA, May 1942 Glendale, CA, c. 16 Aug-16 Sep 1942 Northern Ireland, Oct 1942 Telergma, Algeria, Jan 1943 Berteaux, Algeria, 28 Mar 1943 Souk-el-Arba, Algeria, 13 Jun 1943 Grombalia, Tunisia, 3 Aug 1943 San Pancrazio, Italy, c. 3 Oct 1943 Lecce, Italy, 10 Oct 1943 Vincenzo Airfield, Italy, n Jan 1944 Lesina, Italy, c. 30 Aug-9 Sep 1945 Grenier Field, NH, 12 Apr 1947-2 Oct 1949 New Castle County Aprt, DE, 18 Aug 1955 ASSIGNMENTS Twelfth Air Force Fifteenth Air Force Strategic Air Command Continental Air Command Air Defense Command WEAPON SYSTEMS P-38 P-51 F-94 COMMANDERS 1LT Charles T. Duke, Feb 1942 Col Robert Israel Jr., May 1942 LTC William E. Covington Jr., 17 Jun 1942 Col John W. Weltman, 4 May 1943 LTC Ernest C. Young, 2 Aug 1943 LTC George M. MacNicol, 26 Aug 1943 Col William P. Litton, Jan 1944 LTC Ben A. Mason Jr., 4 Aug 1944 Col Clarence T. Edwinson, 28 Aug 1944 Col Richard A. Legg, 22 Nov 1944 Col Joseph S. Holtoner, 4 Jun 1945 LTC Robert M. Wray, 16 Jul 1945-unkn Maj Leland R. Raphun, Apr 1947 LTC Gerald W. Johnson, 2 Jun 1947 Col Henry Viccellio, 14 Jun 1947 Col William M. -

Operation of the Air Force Educational Program at Otis Air Force Base

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1965 Operation of the Air Force educational program at Otis Air Force Base. Russell R. Kenyon University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Kenyon, Russell R., "Operation of the Air Force educational program at Otis Air Force Base." (1965). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 2980. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/2980 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OPERATION OF TIIE AIR FORCE EDUCATIONAL PROGRAM AT OTIS AIR FORCE BASE by Russell R. Kenyon Problem presented In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Education. School of Education University of Massachusetts Amherst, Massachusetts 1965 t TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Pag© LIST OF TABLES. vi LIST OF CHARTS.... viil Chapter X. INTRODUCTION . .. 2 The United States Air Force II. OTIS AIR FORCE BASE. 29 III. THE OTIS AIR FORCE BASE EDUCATION CENTER ... i& IV. ADMINISTRATIVE PROCESSES WITHIN THE EDUCATION CENTER. 61 The Educational Plant Class Policies Discipline V. EDUCATIONAL PROGRAMS .. 87 Introduction to Educational Programs VI. SUMMARY .. 109 APPENDIX. 125 BIBLIOGRAPHY .. 137 iv LIST OF TABLES LIST OP TABLES Table Page 1* Crew Positions and Approximate Training Time Required for Minimum Proficiency •••«•• 3k 2• Number and Type of Staff Member Authorized • • $0 3. Administrative Enrollments ••••••«*•« 63 It* Educational Programs of the U*S, Air Force Offered at Otis Air Force Base.