HQ PA ANG.Docx

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

26Th AIR DIVISION

26th AIR DIVISION MISSION LINEAGE 26th Air Defense Division established, 21 Oct 1948 Activated, 16 Nov 1948 Redesignated 26th Air Division (Defense), 20 Jun 1949 Inactivated, 1 Feb 1952 Organized, 1 Feb 1952 Redesignated 26th Air Division (SAGE), 8 Aug 1958 Redesignated 26th Air Division, 1 Apr 1966 Inactivated, 30 Sep 1969 Activated, 19 Nov 1969 Inactivated, 30 Sep 1990 STATIONS Mitchel AFB, NY, 16 Nov 1948 Mitchel AFB Sub Base #3, Roslyn, NY, 18 Apr 1949-1 Feb 1952 Mitchel AFB Sub Base #3, Roslyn (later, Roslyn AFS), NY, 1 Feb 1952 Syracuse AFS, NY, 15 Aug 1958 Hancock Field, NY, 14 Feb 1959 Stewart AFB, NY, 15 Jun 1964 Adair AFS, OR, 1 Apr 1966-30 Sep 1969 Luke AFB, AZ, 19 Nov 1969 March AFB, CA, 31 Aug 1983-1 Jul 1987 ASSIGNMENTS First Air Force, 16 Nov 1948 Air Defense Command, 1 Apr 1949 First Air Force, 16 Nov 1949 Eastern Air Defense Force, 1 Sep 1950-1 Feb 1952 Eastern Air Defense Force, 1 Feb 1952 Air Defense Command, 1 Aug 1959 Fourth Air Force, 1 Apr 1966-30 Sep 1969 Tenth Air Force, 19 Nov 1969 Aerospace Defense Command, 1 Dec 1969 Tactical Air Command, 1 Oct 1979 First Air Force, 6 Dec 1985-30 Sep 1990 ATTACHMENTS Eastern Air Defense Force, 17 Nov 1949-31 Aug 1950 COMMANDERS Unkn (manned at paper unit strength), 16 Nov 1948-31 Mar 1949 Col Ernest H. Beverly, 1 Apr 1949 BG Russell J. Minty, Nov 1949 Col Hanlon H. Van Auken, 1953 BG James W. McCauley, 1 Apr 1953 BG Thayer S. -

United States Air Force and Its Antecedents Published and Printed Unit Histories

UNITED STATES AIR FORCE AND ITS ANTECEDENTS PUBLISHED AND PRINTED UNIT HISTORIES A BIBLIOGRAPHY EXPANDED & REVISED EDITION compiled by James T. Controvich January 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTERS User's Guide................................................................................................................................1 I. Named Commands .......................................................................................................................4 II. Numbered Air Forces ................................................................................................................ 20 III. Numbered Commands .............................................................................................................. 41 IV. Air Divisions ............................................................................................................................. 45 V. Wings ........................................................................................................................................ 49 VI. Groups ..................................................................................................................................... 69 VII. Squadrons..............................................................................................................................122 VIII. Aviation Engineers................................................................................................................ 179 IX. Womens Army Corps............................................................................................................ -

ADC and Antibomber Defense, 1946-1972

Obtained and posted by AltGov2: www.altgov2.org ADC HISTORICAL STUDY NO. 39 THE AEROSPACE DEFENSE COMMAND AND ANTIBOMBER DEFENSE 194& -1972 ADCHO 73-8-17 FOREWORD" The resources made available to the Aerospace Defense Command (and the predecessor Air Defense Command) for defense against the manned bomber have ebbed and flowed with changes in national military policy. It is often difficult to outline the shape of national policy, however, in a dynamic society like that of the United States. Who makes national policy? Nobody, really. The armed forces make recommenda tions, but these are rarely accepted, in total, by the political administration that makes the final pbrposals to Congress. The changes introduced at the top executive level are variously motivated. The world political climate must be considered, as must various political realities within the country. Cost is always a factor and a determination must be made as to the allocation of funds for defense as opposed to allocations to other government concerns. The personalities, prejudices and predilections of the men who occupy high political office invariably affect proposals to Congress. The disposition of these proposals, of course, is in the hands of Congress. While the executive branch of the government is pushect' and pulled in various directions, Congress is probably subject to heavier pressures. Here, again, the nature of the men who occupy responsible positions within the Congress often affect the decisions of Congress. ·National policy, then, is the product of many minds and is shaped by many diverse interests. The present work is a recapitulation and summarization of three earlier monographs on this subject covering the periods 1946-1950 (ADC Historical Study No. -

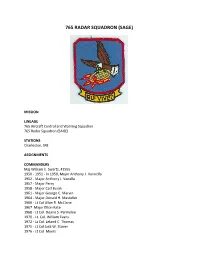

765 Radar Squadron (Sage)

765 RADAR SQUADRON (SAGE) MISSION LINEAGE 765 Aircraft Control and Warning Squadron 765 Radar Squadron (SAGE) STATIONS Charleston, ME ASSIGNMENTS COMMANDERS Maj William E. Swartz, #1955 1950 - 1951 - In 1950, Major Anthony J. Vannella 1952 - Major Anthony J. Vanella 1957 - Major Perry 1958 - Major Carl Burak 1961 - Major George C. Marvin 1964 - Major Donald H. Masteller 1966 - Lt Col Allan R. McClane 1967 Major Elton Kate 1968 - Lt Col. Deane S. Parmelee 1970 - Lt. Col. William Evans 1972 - Lt Col. Leland C. Thomas 1975 - Lt Col Jack W. Stover 1976 - Lt Col. Myers 1979 - Major Stymeist HONORS Service Streamers Campaign Streamers Armed Forces Expeditionary Streamers Decorations EMBLEM EMBLEM SIGNIFICANCE MOTTO NICKNAME OPERATIONS MAINE P-65/Z-65 - Charleston The 765th AC&W Squadron brought Charleston AFS to life in April 1952 and assumed coverage that had been provided by a Lashup site at Dow AFB (L-l). The site initially had AN/FPS-3 and 5 radars. In 1957 an AN/FPS-6 replaced the AN/FPS-5 height-finder radar. Another height-finder radar came in 1958 along with an AN/FPS-20 search radar that replaced the AN/FPS-3. During 1959 Charleston joined the SAGE system. In 1963 the site became the first in the nation to receive an AN/FPS-27. This radar subsequently was upgraded to become an ANFPS-27A. The 765th was deactivated in September 1979. The 765th AC&W Squadron brought Charleston AFS to life in April 1952 and assumed coverage that had been provided by a Lashup site at Dow AFB (L-l). -

Almanac ■ Guide to Air Force Installations Worldwide

USAFAlmanac ■ Guide to Air Force Installations Worldwide Major Installations Note: A major installation is an Air Force Base, Air Andrews AFB, Md. 20762-5000; 10 mi. SE of 4190th Wing, Pisa, Italy; 31st Munitions Support Base, Air Guard Base, or Air Reserve Base that Washington, D. C. Phone (301) 981-1110; DSN Sqdn., Ghedi AB, Italy; 4190th Air Base Sqdn. serves as a self-supporting center for Air Force 858-1110. AMC base. Gateway to the nation’s (Provisional), San Vito dei Normanni, Italy; 496th combat, combat support, or training operations. capital and home of Air Force One. Host wing: 89th Air Base Sqdn., Morón AB, Spain; 731st Munitions Active-duty, Air National Guard (ANG), or Air Force Airlift Wing. Responsible for Presidential support Support Sqdn., Araxos AB, Greece; 603d Air Control Reserve Command (AFRC) units of wing size or and base operations; supports all branches of the Sqdn., Jacotenente, Italy; 48th Intelligence Sqdn., larger operate the installation with all land, facili- armed services, several major commands, and Rimini, Italy. One of the oldest Italian air bases, ties, and support needed to accomplish the unit federal agencies. The wing also hosts Det. 302, dating to 1911. USAF began operations in 1954. mission. There must be real property accountability AFOSI; Hq. Air Force Flight Standards Agency; Area 1,467 acres. Runway 8,596 ft. Altitude 413 through ownership of all real estate and facilities. AFOSI Academy; Air National Guard Readiness ft. Military 3,367; civilians 1,102. Payroll $156.9 Agreements with foreign governments that give Center; 113th Wing (D. C. -

16004491.Pdf

-'DEFENSE ATOMIC SUPPORT AGENCY Sandia Base, Albuquerque, New Mexico ,L/PE - 175 Hi%&UhIiT~ SAIdDIA BASE ALBu2umxJE, la$ mXIc0 7 October 1960 This is to cert!e tlmt during the TDY period at this station, Govement Guarters were available and Goverrrment Fessing facilities were not availzble for the following mmoers of I%Ki: Colonel &w, Og~arHe USA Pi3 jor Andm~n,Qaude T. USAF Lt. Colonel fsderacn, George R. USAF Doctor lrndMvrsj could Re Doctor Acdrem, Howard L. USPIG Colonel ksMlla stephen G. USA Colonel Ayars, Laurence S. USAF Lt. Colonel Bec~ew~ki,Zbignie~ J. USAF Lt. Colonel BaMinp, George S., Jr. USAF bjor Barlow, Lundie I:., Jr. UMG Ckmzzder m, h3.llian E. USPHS Ujor Gentley, Jack C. UskF Colonel Sess, Ceroge C. , WAF Docto2 Eethard, 2. F. Lt. c=Jlonel Eayer, David H., USfiF hejor Bittick, Paul, Jr. USAF COlOIle3. Forah, hUlhm N. USAF &;tail? Boulerman, :!alter I!. USAF Comander hwers, Jesse L. USN Cz?trin Brovm, Benjamin H, USAF Ca?tain Bunstock, lrKulam H. USAF Colonel Campbell, lkul A. USAF Colonel Caples, Joseph T. USA Colonel. Collins, CleM J. USA rmctor Collins, Vincent P. X. Colonel c0nner#, Joseph A. USAF Cx:kain ktis, Sidney H. USAF Lt. Colonel Dauer, hxmll USA Colonel kvis, Paul w, USAF Captsir: Deranian, Paul UShT Loctcir Dllle, J. Robert Captain Duffher, Gerald J. USN hctor Duguidp Xobert H. kptain arly, klarren L. use Ca?,kin Endera, Iamnce J. USAF Colonel hspey, James G., Jr. USAF’ & . Farber, Sheldon USNR Caifain Farmer, C. D. USAF Ivajor Fltzpatrick, Jack C. USA Colonel FYxdtt, Nchard s. -

The Ground Observer Corps Public Relations and the Cold War in the 1950S

The Ground Observer Corps Clymer The Ground Observer Corps Public Relations and the Cold War in the 1950s ✣ Kenton Clymer Ground Observer Corps, Hurray! Protects our Nation every day. Protects our ºag, Red, White and Blue, They protect everyone, even you. Always on guard with Watchful eyes, Never tiring they search the skies. From now to eternity we shall be free, America’s guarded by the G. O. C. Tony Parinelli, Leominster, MA1 This article examines the development and demise of one of the least studied elements of U.S. homeland defense efforts in the 1950s: the Ground Ob- server Corps (GOC). In an earlier article I explored the origins of the GOC.2 Here I focus on the development of the organization in the mid-1950s until its deactivation in 1959, showing that the GOC never came close to achieving its goals for recruitment and effectiveness. Despite the grave shortcomings of the GOC, the U.S. Air Force (USAF) continued to support the organization, evidently because the GOC served the public relations interests of the Air Force, U.S. air defense, and, more generally, the Cold War policies of the United States. The lack of widespread public support for the GOC provides some credence to the contrarian view about the overwhelming fear of an im- minent Soviet nuclear strike on the United States that is commonly said to have characterized U.S. society in the 1950s.3 1. Tony Parinelli, “G.O.C.,” in Dwight D. Eisenhower Library (DDEL), White House Central Files (WHCF), Dwight D. Eisenhower Papers, Ofªcial File 1953–1961, Box 82, Folder 3-C-14 (1). -

Usafalmanac ■ Guide to Air Force Installations Worldwide

USAFAlmanac ■ Guide to Air Force Installations Worldwide Major Installations Note: A major installation is an Air Force Base, Air Andrews AFB, Md. 20762-5000; 10 mi. SE of port Sq., Araxos AB, Greece; Det. 1, Expeditionary Base, Air Reserve Base, or Air Guard Base that Washington. Phone (301) 981-1110; DSN 858-1110. Air Control Sq., Jacotenente, Italy. One of the old- serves as a self-supporting center for Air Force AMC base. Host: 89th Airlift Wing. Responsible for est Italian air bases, dating to 1911. USAF began combat, combat support, or training operations. Presidential support and base operations; supports operations 1954. Area 1,467 acres. Runway 8,596 Active duty, Air National Guard (ANG), or Air Force all branches of the armed services, several major ft. Altitude 413 ft. Military 3,367; civilians 1,102. Reserve Command (AFRC) units of wing size or commands, and federal agencies. Tenants: Det. Payroll $158.9 million. Housing: 619 govt.-leased larger operate the installation with all land, facili- 302, AFOSI; Air Force Flight Standards Agency; units, 34 billeting spaces, 552-bed dorm. No ties, and support needed to accomplish the unit AFOSI Academy; Air National Guard Readiness TLF, 20 VOQ, 14 VAQ. Clinic with 24-hour acute- mission. There must be real property accountability Center; 113th Wing (D.C. ANG); 459th Airlift Wing care clinic. American medical services at Sacile through ownership of all real estate and facilities. (AFRC); Naval Air Facility; Marine Aircraft Gp. 49, Hospital (20 minutes from base) with OB/GYN, Agreements with foreign governments that give Det. A; Air Force Review Boards Agency. -

58Th FIGHTER SQUADRON

58th FIGHTER SQUADRON MISSION The 58th FS “Mighty Gorillas” are authorized to operate 24 assigned F-35A aircraft, planning and executing a training curriculum in support of Air Force and international partner pilot training requirements. LINEAGE 58th Pursuit Squadron (Interceptor) constituted, 20 Nov 1940 Activated, 15 Jan 1941 Redesignated 58th Fighter Squadron, 15 May 1942 Redesignated 58th Fighter Squadron, Two Engine, 8 Feb 1945 Inactivated, 8 Dec 1945 Redesignated 58th Fighter Squadron, Single Engine, 17 Jul 1946 Activated, 20 Aug 1946 Redesignated 58th Fighter Squadron, Jet, 14 Jun 1948 Redesignated 58th Fighter Interceptor Squadron, 20 Jan 1950 Discontinued and inactivated, 25 Dec 1960 Redesignated 58th Tactical Fighter Squadron, 16 Mar 1970 Activated, 1 Sep 1970 Redesignated 58th Fighter Squadron, 1 Nov 1991 STATIONS Mitchel Field, NY, 15 Jan 1941 (operated from Farmingdale, NY, 7–14 Dec 1941) Philadelphia, PA, 13 Dec 1941 Norfolk, VA, 16 Jan 1942 (operated from San Francisco, CA, May–Jun 1942) Langley Field, VA, 22 Sep–14 Oct 1942 Port Lyautey, French Morocco, 10 Nov 1942 Thelepte, Tunisia, 12 Dec 1943 Telergma, Algeria, 7 Feb 1943 Berteaux, Algeria, 2 Mar 1943 Ebba Ksour, Tunisia, 13 Apr 1943 Menzel Temime, Tunisia, 15 May 1943 Pantelleria, 28 Jun 1943 Licata, Sicily, 18 Jul 1943 Paestum, Italy, 14 Sep 1943 Santa Maria, Italy, 18 Nov 1943 Cercola, Italy, 1 Jan–6 Feb 1944 Karachi, India, 18 Feb 1944 Pungchacheng, China, c. 30 Apr 1944 Moran, India, 31 Aug 1944 Sahmaw, Burma, 26 Dec 1944 Dudhkundi, India, c. 15 May–15 Nov 1945 -

Circumpolar Military Facilities of the Arctic Five

CIRCUMPOLAR MILITARY FACILITIES OF THE ARCTIC FIVE Ernie Regehr, O.C. Senior Fellow in Arctic Security and Defence The Simons Foundation and Michelle Jackett, M.A. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Circumpolar Military Facilities of the Arctic Five – last updated: September 2017 Ernie Regehr, O.C., and Michelle Jackett, M.A. Circumpolar Military Facilities of the Arctic Five Introduction This compilation of current military facilities in the circumpolar region1 continues to be offered as an aid to addressing a key question posed by the Canadian Senate more than five years ago: “Is the [Arctic] region again becoming militarized?”2 If anything, that question has become more interesting and relevant in the intervening years, with commentators divided on the meaning of the demonstrably accelerated military developments in the Arctic – some arguing that they are primarily a reflection of increasing military responsibilities in aiding civil authorities in surveillance and search and rescue, some noting that Russia’s increasing military presence is consistent with its need to respond to increased risks of things like illegal resource extraction, terrorism, and disasters along its frontier and the northern sea route, and others warning that the Arctic could indeed be headed once again for direct strategic confrontation.3 While a simple listing of military bases, facilities, and equipment, either -

84Th FLYING TRAINING SQUADRON

84th FLYING TRAINING SQUADRON MISSION LINEAGE 84th Pursuit Squadron (Interceptor) constituted, 13 Jan 1942 Activated, 9 Feb 1942 Redesignated 84th Pursuit Squadron (Interceptor) (Twin-Engine), 22 Apr 1942 Redesignated 84th Fighter Squadron (Twin-Engine), 15 May 1942 Redesignated 84th Fighter Squadron, 1 Mar 1943 Redesignated 84th Fighter Squadron, Single-Engine, 21 Aug 1944 Inactivated, 18 Oct 1945 Activated, 20 Aug 1946 Redesignated 84th Fighter Squadron, Jet, 24 Sep 1948 Redesignated 84th Fighter Interceptor Squadron, 20 Jan 1950 Redesignated 84th Fighter Interceptor Training Squadron, 1 Jul 1981 Inactivated, 27 Feb 1987 Redesignated 84th Flying Training Squadron, 9 Feb 1990 Activated, 2 Apr 1990 Inactivated, 1 Oct 1992 Activated, 1 Oct 1998 STATIONS Baer Field, IN, 9 Feb 1942 Muroc, CA, 30 Apr 1942 Oakland, CA, 11 May 1942 Hamilton Field, CA, 4-10 Nov 1942 Goxhill, England, 1 Dec 1942 Duxford, England, 1 Apr 1943-11 Oct 1945 Camp Kilmer, NJ, 16-18 Oct 1945 Straubing, Germany, 20 Aug 1946-25 Jun 1947 Mitchel Field, NY, 25 Jun 1947 Hamilton AFB, CA, 24 Nov 1948 Castle AFB, CA, 1 Sep 1973-27 Feb 1987 Laughlin AFB, TX, 2 Apr 1990-1 Oct 1992 Laughlin AFB, TX, 1 Oct 1998 ASSIGNMENTS 78th Pursuit (later, 78th Fighter) Group, 9 Feb 1942-18 Oct 1945 78th Fighter (later, 78th Fighter Interceptor) Group, 20 Aug 1946 4702nd Defense Wing, 6 Feb 1952 28th Air Division, 7 Nov 1952 566th Air Defense Group, 16 Feb 1953 78th Fighter Group, 18 Aug 1955 78th Fighter Wing, 1 Feb 1961 1st Fighter Wing, 31 Dec 1969 26th Air Division, 1 Oct 1970-27 Feb 1987 47th Flying Training Wing, 2 Apr 1990 47th Operations Group, 15 Dec 1991-1 Oct 1992 47th Operations Group, 1 Oct 1998 WEAPON SYSTEMS P-38, 1942-1943 P-47, 1943-1944 P-51, 1944-1945 F-51, 1949-1951 F-84, 1949-1951 F-89, 1951-1952 F-86, 1952-1958 F-89, 1958-1959 F-101, 1959-1968 F-106, 1968-1981 F-106A F-106B T-33, 1981-1987 T-37, 1990-1992 P-47C P-47D P-51B P-51D P-51K F-84D F-89B F-94B P-38E P-38F F-101B F-101F COMMANDERS Maj Eugene P. -

551St ELECTRONIC SYSTEMS WING

551st ELECTRONIC SYSTEMS WING MISSION The 551st Electronic Systems Wing, a unit of the Air Force Electronic Systems Center at Hanscom AFB, MA, delivers superior capabilities from assigned programs: AWACS, Joint STARS, E-10A/MP- RTIP, Mission Planning, and Weather providing strategic support to ongoing operations, identifying capability information integration opportunities and equipping the war fighter with the technical edge needed to meet comBatant mission requirements. The wing's mission is execute a $12 Billion in approved program funds to develop, provide, sustain and evolve integrated current and future surveillance, Battle planning, Battle management, and battle execution capabilities to meet United States and Allied and Coalition requirements By teaming with the war fighter, industry, and enterprise partners. The mission is accomplished from the resources of four Electronic Systems Groups (ELSG) and one direct reporting division. LINEAGE 51st Transport Wing Established, 30 May 1942 Activated, 1 Jun 1942 Redesignated 51st Troop Carrier Wing, 4 Jul 1942 Inactivated, 5 Jan 1948 Disestablished, 15 Jun 1983 551st AirBorne Early Warning and Control Wing, established, 11 Oct 1954 Activated, 18 Dec 1954 Inactivated, 31 Dec 1969 51st Troop Carrier Wing and 551st AirBorne Early Warning and Control Wing reestablished, consolidated and redesignated 551st AirBorne Warning and Control Wing, 31 Jul 1985 Battle Management Systems Wing, established, 23 Nov 2004 Activated, 17 Dec 2004 551st AirBorne Warning and Control Wing and Battle Management