Return Migrationandidentity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mitteilungen Wissens Zentrum

90 Jahre designaustria! 90 Jahre, Ein Jahr besteht nun der Young in denen wir uns wichtigen Fragen ExpertsCluster. Ein Jahr, in dem zu Design in Österreich widmen wir verstärkt auf die Fragen junger — von den kleinen bis zu den DesignerInnen eingingen. Von „Wie Wer? großen. Von „Wie bewahrst du kann ich mein Portfolio aufbauen?“ dir deine Kreativität?“ bis zu „Was bist zu „Wie erging es anderen muss sich in Österreich zugunsten GestalterInnen bei ihrem Berufs des Designs verbessern?“ Die einstieg?“ Einige Fragen, die wir Antworten sind oft nicht leicht. uns stellen, sind hier gesammelt. Um aber auf diese aktuellen und Auf viele haben wir noch nicht Wie? zukünftigen Fragen rechtzeitig die richtigen Antworten gefunden reagieren zu können, braucht es — machen wir das gemeinsam! eine gute Interessen vertretung Schreib uns auf Facebook oder und ein starkesmitteilungen Wissens zentrum. unter [email protected]. Wir freuen uns auf dich! Typografie: Subtext: Typedesign – EineAnna Werkschau Rose, österreichischer Agnes, Nicole, Sebastian Wo? Schriftgestaltung | Österreichisches Grafikdesign: Nicht in Österreich, doch in der Welt weltbekannt | Bücher: »Typojis« von Walter Bohatsch & »Arabic Type-Making in the Machine Age von Titus Nemeth« | Studioporträt: Schriftlabor: Der kleine Riese der österreichischen Schriftgestaltung | Wie bewahrst du dir 90 Jahre designaustria: Young ExpertsCluster | Staatspreis Design & deine Kreativität? Sonderpreis DesignConcepts 2017 | Vienna Design Week 2017 1 . 2 . 3 . 4 2017 ཌྷཌྷཌྷཌྷཌྷཌྷཌྷProkrastination Wem? -

A Chinese Graphic Design History in Greater China Since 1979 Wendy Siuyi Wong

Detachment and Unification: A Chinese Graphic Design History in Greater China Since 1979 Wendy Siuyi Wong The illustrations are identified by the name of Introduction designer, the client or title of the work, the The history of modern Chinese design is virtually unknown due to design category, and the year. The title of the its relatively late development compared to design in the West. Not work is the author’s own title, if an official until recent decades, since the opening up of China in 1979, has a name is cannot found. All woks reprinted with unifying Chinese graphic design history started to form. This was permission of the designer. assisted by China’s rapid economic development and interactions with Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Macau; which, together with main- land China, make up the Greater China region. Traditionally, in academic practice, it was common to separate the investigation of these individual Chinese societies. Matthew Turner, one of the few Western historians to examine Chinese design, notes that the history of Hong Kong design prior to the 1960s “simply was believed not to 1 2 1 Matthew Turner, “Early Modern Design in exist.” Chinese-trained design scholar Shou Zhi Wong emphasizes Hong Kong” in Dennis P. Doordan, ed., that there has been very little written about modern design in main- Design History: An Anthology land China, because design activity under the communists before (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1995), 212. This the start of the Open Door Policy in 1979 was mostly in the service article was first published in Design of party propaganda.3 Both Turner and Wang, as well as Scott Issues, 6:1 (Fall 1989): 79–91; also Matthew Turner, “Development and Minick and Jiao Ping, published their works on Chinese design Transformations in the Discourse of history before a number of key economic and political changes in Design in Hong Kong” in Rajeshwari China and Hong Kong took place. -

Must See? Kunst, an Der Man Nicht Vorbeikommt

DIE ZEITUNG DER KULTURVERNETZUNG NIEDERÖSTERREICH AUSGABE N R. 31 / JUNI 2020 Must see? Kunst, an der man nicht vorbeikommt „Bläst für 3 Asse” – Thomas Webers Betrachtungen zu Denkmälern in Strasshof Wunderbare Symbiosen – Sandra Schäfer zu Besuch bei Isabell Kneidinger Die Fahrrad-Verwandler – Isabella Marboe über das Upcycling-Projekt „Fahrradfilet“ Der erste Grafikdesigner – Ernst Schmiederer hat mit Designer-Legende Henry Steiner gesprochen 2 Titel kunstStoff Nr. 31 / Juni 2020 RANDBEMERKUNGEN EINE ART VON EDITORIAL Als die Kunst den Raum eroberte Liebe Leserin, lieber Leser! Ursprünglich wollten wir diese Ausgabe des kunstSTOFF Ende März veröffent - lichen. Dann kam das Virus, mit ihm ein weitgehendes Verbot des Aufenthaltes im Freien, und es erschien uns nicht passend, ausgerechnet zu einem solchen Zeitpunkt ein Loblied auf die öffentlich zugängliche Kunst zu singen. Jetzt geht es wieder, und wir sind froh darüber. Kunst soll uns auf Schritt und Tritt verfolgen, überraschen, überfallen. Kunst im öffent - lichen Raum ist dafür besonders gut geeignet. Gehen Sie raus. Suchen und fin - den Sie Kunst. Haben Sie eine Meinung dazu. Wenn Sie eine künstlerische Arbeit scheußlich finden, ist das Ihr gutes Recht als Betrachterin/Betrachter. Kunst muss 2019 gestaltete der Künstler Moussa Kone „Circulus Vitiosus (Make it Greta)“ als Auftragsarbeit an einer Hausfassade in St. Leonhard am Forst nicht schön sein; sie muss auch nicht gefallen. Die Kunst hat keine Eigentümer, VON ERWIN UHRMANN in Vereinen und engagierten sich je nach ihren auch wenn man seit vielen Jahrhunderten jeweiligen Interessen. trefflich damit Geschäfte machen kann. Das Fördermodell „Kunst am Bau“, das vor - Sie gehört allen. Sie ist neben der Wissen- Was öffentlich ist, wird auch offen sieht, etwa ein Prozent der Kosten öffentlicher schaft das wichtigste immaterielle Erbe diskutiert: ob Street-Art, Land-Art Bauten in Kunst zu investieren, begann sich der Menschheit und das sichtbarste nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg in einigen Zeichen für Gedankenfreiheit, das wir oder Installationen. -

Mitteilungen

mitteilungen Gestaltung für die Erde mit viel beherztem Grün | Circular Flows: The Toilet Revolution! von EOOS | FH Salzburg: So wird man Circular-Economy-Experte/Expertin! | Staatspreis Design & Sonderpreis DesignConcepts 2019: Shortlist | Ausstellung in China: Henry Steiner • Graphic Communicator | 95: Happy Birthday, »novum«! | TramThings 3437 – Wiener Straßenbahnplakate der 1950er-Jahre | Plakate im Zeichen der Zeit: Paul Rataitz (1926–2019) | #DENKWEITER: designaustria-Fortbildungsprogramm September – Dezember 2019 | Vienna Design Week 2019 1 . 2 . 3 . 4 2019 Jianping He: Ausstellungsplakat »Henry Steiner . Graphic Communicator« 02 MITTEILUNGEN 03.2019 Inhalt INHALT q Designbriefmarke mit dem MAM-Schnuller »START« von Ernst W. Beranek NACHHALTIGKEIT DESIGNAUSTRIA- 04 04 Gestaltung für die Erde mit viel 26 STUDIOPORTRÄT beherztem Grün – Interview mit 26 tomasini design Angie Rattay 08 Circular Flows: The Toilet Revolution! – EOOS gewinnt in Mailand Black Bee Award in Silber NACHRUF 09 »Fatimas fantastische Reise in eine 29 29 Plakate im Zeichen der Zeit: Welt ohne Erdöl« von Jakob Winkler Paul Rataitz (1926–2019) AUSBILDUNG RÜCKSCHAU 10 10 FH Salzburg: So wird man Circular- 30 30 Hollenegger Designgespräche: Economy-Experte/Expertin! Wie die richtige Gestaltung zum Erfolg führt STAATSPREIS DESIGN MEMBERS@WORK 11 11 Bekenntnis zur Zukunft durch Wirtschaftlichkeit und Nachhaltigkeit: 31 31 It’s a Passion Thing Staatspreis Design & Sonderpreis 31 Damen, die zeichnen DesignConcepts 2019 32 Über den Dingen 13 Staatspreis Design 2019 – 32 Raue, magische Natur Ausstellung und Katalog 33 Strukturierte Weinlandschaft 14 Shortlist 33 Ein Toast auf Wien 34 Wein und sonst (fast) nix 34 Rückenprotektion neu gedacht FEATURE 16 16 Henry Steiner • Graphic Communicator VERANSTALTUNGEN 18 »I love to solve communication problems for others!« 35 35 Vienna Design Week 2019 19 Weggefährtinnen und Weggefährten 36 #DENKWEITER: Fortbildungspro- über Henry Steiner gramm September – Dezember 2019 20 Henry Steiner: »Ich brauche keinen 38 Stadt.Land.Schluss. -

Kurzbiografien – Band 4 Der „Erinnerungen. Lebensgeschichten Von Opfern Des Nationalsozialismus“ Short Biographies – Volume 4 of „Lives Remembered

Kurzbiografien – Band 4 der „Erinnerungen. Lebensgeschichten von Opfern des Nationalsozialismus“ Short biographies – Volume 4 of „Lives remembered. Life stories of Victims of National Socialism” Band 4/1 Volume 4/1 Felix Lee wurde als Sohn der jüdischen Wienerin Felix Lee was born to the Viennese Jewish Elisabeth Elisabeth Heinrich und des Chinesen Lee Wei Ning am Heinrich and the Chinese Lee Wei Ning on 9 9. September 1935 in Wien geboren. Als Säugling September 1935 in Vienna. As an infant he briefly verbrachte er kurze Zeit in Shanghai, bevor seine lived in Shanghai before returning to Vienna with his Mutter mit ihm im März 1936 wieder nach Wien mother in March 1936. Protected by the Chinese zurückkehrte. Geschützt durch die chinesische citizenship and the remarriage of his mother with the Staatsbürgerschaft und eine neuerliche Ehe seiner Chinese Chang Lin Hop, they both survived the Mutter mit dem Chinesen Chang Lin Hop, überlebten Holocaust in Vienna. Felix Lee later studied accordion, die beiden den Holocaust in Wien. Felix Lee studierte piano and composition at the Conservatory of the später am Konservatorium der Stadt Wien City of Vienna and for many years was an active Akkordeon, Klavier und Komposition und music teacher at adult education centers and music unterrichtete als Musiklehrer viele Jahre an schools of the City of Vienna. Volkshochschulen und an den Musiklehranstalten der Stadt Wien. Herbert Zipper wurde am 27. April 1904 in Wien Herbert Zipper was born on 27 April 1904 in Vienna. geboren. Er entstammte einer wohlhabenden He was from a wealthy Jewish family and studied jüdischen Familie und studierte in seiner Heimatstadt music in his hometown in the 1920s. -

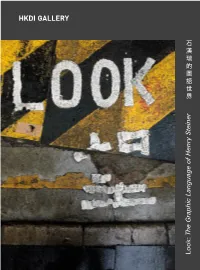

Look: the Graphic Language of Henry Steiner 界 世 語 圖 的 瑞 漢 石 Foreword 前言

Look: The Graphic Language of Henry Steiner 石 漢 瑞 的 圖 語 世 界 Foreword 前言 Hong Kong Design Institute’s mission is to develop 香港知專設計學院以培養創意人才為使 creative talents who are not only competent prac- 命,讓他們不僅成為各領域中出色的人 titioners in their respective fields, but also thinking 才,更能蛻變成高瞻遠矚的專業人士。 professionals who are future-ready. We believe that 觀察和反思對於任何創意人才的成長尤 an active process of looking and reflecting is impor- 其重要,而我們的展覽正正提供所需的 tant for the growth of any creative practitioner. Our 教育體驗。 gallery exhibitions provide an educational experi- ence that does precisely that. 石漢瑞的作品不需多費筆墨介紹。無處 The work of Henry Steiner needs little introduction. 不在的滙豐銀行標誌、大家錢包中的渣 The ubiquitous HSBC symbol around the street cor- 打銀行紙幣都出自他的手筆,已經成為 ner, the Standard Chartered banknotes in our wallet 我們日常生活不可或缺的一部分。石漢 – his work is an integral part of our everyday lives. 瑞兒時從奧地利逃難到紐約,1961年 As a sojourner who escaped from Austria to New 移居香港,繼而為我們確立平面設計作 York and ultimately Hong Kong in 1961, Steiner 為一門專業的地位。 was responsible for introducing graphic design as a profession to Hong Kong. 《石漢瑞的圖語世界》 展示了職業訓練 局榮譽院士石漢瑞先生充滿傳奇的職業 Look: The Graphic Language of Henry Steiner cel- Look: The Graphic Language of Henry Steiner 生涯。策展過程中,我們嘗試解構為何 ebrates the achievements of VTC Honorary Fellow 他的作品能拔萃出群︒他積極的觀察如 石漢瑞的圖語世界 Henry Steiner’s storied career. Through the curato- 何轉化為強而有力的圖像設計?展覽既 rial process, we attempt to extrapolate what makes his work outstanding: how does his active process 展示了石漢瑞的標誌性作品,同時提出 of looking transform into graphic communications 多個問題,以激發好奇心,促使大家觀 that are powerfully persuasive? In showing you 察得更仔細、目光放得更長遠,帶着新 Henry Steiner’s iconic work, we attempt to ask 的啟發繼續創意之旅。 questions that pique your curiosity to look closer, 10 April – 30 May 2021 2021年4月10日至 5月30日 王麗蓮博士 look further and be inspired to continue your jour- 10:00 – 20:00 上午10:00—晚上8:00 ney of creativity. -

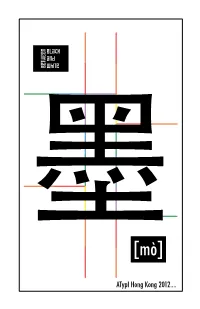

Atypi Hong Kong 2012

Black and Between White 墨 [mò] ATypI Hong Kong 2012.... Theme Venues The theme of this years conference is 墨 [mò] - The 2012 conference uses three superb venues within between black and white. Mò - meaning ink - is at the easy reach of one another. heart of Chinese calligraphy and painting as well as a metaphor for intellectual pursuits. ‘Know the white and guard the black`(知白守黑) is an expression from philosopher Lao Tzu that speaks of a virtuous life as Workshops and specialist sessions on Wednesday 10 well as an aesthetic sensibility. A Chinese calligrapher and Thursday 11 October, plus the conference opening aims to achieve equilibrium of black and white not in keynote & reception on Thursday evening, will be held an absolute sense, but an organic and intuitive balance. at InnoCentre. Hotel Icon hosts the ATypI general confer- The importance of the balancing of black and white ence programme from Friday 12 to Sunday 14 October is a shared value between both Eastern and Western typographic cultures. When we put something in black and white, we speak of the essence of the written word as a means to exchange and preserve information and knowledge for all, playing an important role in our Exhibitions will be held on the campus of the Hong Kong culture and society. ‘Between black and white‚‘not only Polytechnic University celebrates this shared tradition but also acknowledges http://www.atypi.org/hong-kong-2012 that black and white form a complementary relationship http://www.qrstuff.com with each other, hence a wide spectrum of viewpoints are possible between the two. -

Servus Hong Kong II

Servus Hong Kong II Austria and the Pearl of the Orient A Sequel to the First Random Visual Walk Down Memory Lane The Austrian Chamber of Commerce is pleased to announce that our edition of “Servus Hong Kong II” has been launched on July 4, 2017. “Servus Hong Kong II.” is a stimulating and historically important compilation of impressions, experiences, and anecdotes rather than just a commercial publication serving as an important snapshot of Austria in the region. About the book Prof. Dr. Gordian GAETA, Chief Editor of Servus Hong Kong II - Gordian Gaeta structures and invests in complex equity transactions often in frontier markets for family offices, private equity funds, and sovereign wealth entities. Gordian was managing partner with Booz & Co, the preeminent management consulting firm and a bank executive in several continents. An academic in law, business, and finance, he authored a number of books and articles. Gordian studied undergraduate mathematics, graduate law, and post graduate business sciences. An Austrian citizen, he resides in Dubai, UAE and Hong Kong. Prof. Dr. Henry Steiner, Designer of Servus Hong Kong II - Henry Steiner is an Austrian graphic designer, best known for his corporate identity designs. Dubbed “father of Hong Kong graphic design”, he has created designs for some of the most identifiable brands, such as IBM, Hyatt Regency, Hilton Hotels, Dow Jones, HSBC, Standard Chartered, Unilever, and was commissioned to design the city's bank notes by the Hong Kong government in 1975. Steiner was educated at the Sorbonne and at Yale. In 1964, he founded his own consultancy firm, Steiner&Co, in Hong Kong. -

Father of HK Design Showcases His Masterpieces in HKBU Exhibition

2004 - 05 2 November 2004 Father of HK Design showcases his masterpieces in HKBU exhibition Henry Steiner, the father of Hong Kong's graphic design and corporate identity industry, is to be awarded the honorary degree of Doctor of Social Sciences from Hong Kong Baptist University (HKBU) to acknowledge his contributions to the design profession and to Hong Kong's education, society and economy in general. A public seminar and an exhibition will be held this week to showcase Mr. Steiner's vision and achievement. Henry Steiner is a man of exceptional talent who has exerted great influence in his profession and to Hong Kong's economic development. Many of Hong Kong's most popular brand names have acquired their striking images due to Mr. Steiner's ingenious designs. His designs have tremendously benefited Hong Kong's business expansion as well. (For details, please visit http://video.hkbu.edu.hk/department/cpro/henrysteiner0a93.asx.) Henry Steiner, Hong Kong's graphic design guru would rather have people known him as a branding consultant. Many of the most popular corporate identities we see daily in the street are the works of him, such as HSBC, the Jockey Club logos and the banknotes of Standard Chartered Bank, etc. Henry Steiner's long list of clients reads like a corporate roll of honor, and it is almost a shame for a large company not to be included. Henry Steiner was born in Austria. He graduated from Hunter College, New York and obtained his Master of Fine Arts degree in Graphic Design from Yale University. -

English Version on Page 3 & 4

(Modified translation from the original German language Profile by Elisabeth Woditschka in Forbes Austria, February 2016.) The Real Steiner In the Chinese New Year of the Fire Monkey, everything seems about money. Austrian-born Henry Steiner is responsible for the design of a set of Hong Kong banknotes. Forbes Austria met the designer in Hong Kong. “I was working for New York agencies and studios during the Mad Men times. The US television show well depicts what Madison Avenue was like as the center of the advertising universe,” said a laid-back Henry Steiner, when we met him in the lobby of the Shangri-La hotel in the heart of the Hong Kong metropolis, where he has resided for over 50 years. To talk with him is to relive the glory of that era. The elegance and clarity of his language and manner explain vividly how the Manhattan of that period felt. Henry Steiner has come a long way, even though he had anything but an easy beginning. A Jew born in 1934, he spent his first years in the comfortable Baden suburb of Vienna. He and his parents escaped the Nazis in late 1939 just before the country was sealed off. Asylum for the Steiner family was, as for many others the same destination: America, specifically, New York. There he grew up in extremely modest circumstances. He studied graphic design at Yale University and returned to work in New York afterwards. He also spent two years in Paris on a Fulbright Scholarship at the Sorbornne. In 1961 he left New York for Hong Kong, recruited as Design Director of The Asia Magazine, a weekly supplement. -

PDF: Newsletter 13 Feb 2018

HENRY STEINER Bridging East and West Austrians in Hong Kong Liebe Landsleute! Dear friends of Austria! The Austrian Consulate General has the honour to introduce you two cultural projects about Professor Henry Steiner. Known as the father of Hong Kong design, Henry Steiner was born in Vienna and with the National Socialists' rise to power fled to and raised in New York. He was educated at Yale and at the Sorbonne. Steiner's experience and reputation are international, he is best known for designing the HSBC corporate identity and logo, as well as several series of banknotes for Standard Chartered Bank. Steiner was named World Master by Japan's Idea magazine, and one of Icograda's Masters of the 20th Century. He received the Governor's Award for Hong Kong Design in 1970; and in 2012, Steiner won the Asian Design Lifetime Achievement Award from the Hong Kong Design Centre. In 2006, Steiner received the Decoration of Merit in Gold of the Republic of Austria for design achievement and nearly 10 years later he got awarded the honorary title of Professor by the Federal President of Austria. Founded in 1927, designaustria is Europe's third oldest design organisation with currently more than 1,300 members from various backgrounds. The organisation aims to raise awareness for design through exhibitions, teaching programmes, publications, and public relations activities, it promotes the benefits of design for society and the economy. design|er|leben is a book series published by designaustria, the series is dedicated to the generation of Austrian designers who shaped the design in the 20th century and beyond. -

Typographic Culture of Hong Kong

Typography in Publication Design Typographic Culture of Hong Kong Mariko Takagi, Academy of Visual Arts, Hong Kong Baptist University, [email protected] Abstract: Does a special and unique typographic culture exist in Hong Kong? And if yes, how is the Hong Kong typographic culture distinguishable from other Asian cultures as China, Japan, Korea, Taiwan, etc.? Who are the leading typographers and what are their missions? How to promote and develop the “typographic culture of Hong Kong” in future not only within the local context, but internationally? This research on “typographic culture in Hong Kong” does not only aim to analyse the current situation but shows ways of creating awareness of the Hong Kong typographic identity and culture in the future. The long-term significance of this project is to promote the international acceptance of Hong Kong (designer/artist) in the field of graphic design and typography in particular. Key words: Hong Kong, typography, Chinese complex characters, typographic design, visual culture, phenomenology 1. Hong Kong – a melting pot Hong Kong is one of the most modern cities in Asia. For many tourists it is one of the most popular and attractive shopping paradises. All the famous international brands are available in this city – from the European and American to the Japanese luxury labels. The other side of the coin is that Hong Kong's super malls look similar to any other super malls of the world. One side effect of the advancing globalization is the process of unifying and the loss of individual visual identity of all these “international” spots.