Human Rights Activists in the Castros' Cuba

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021 International Day of Commemoration in Memory of the Victims of the Holocaust

Glasses of those murdered at Auschwitz Birkenau Nazi German concentration and death camp (1941-1945). © Paweł Sawicki, Auschwitz Memorial 2021 INTERNATIONAL DAY OF COMMEMORATION IN MEMORY OF THE VICTIMS OF THE HOLOCAUST Programme WEDNESDAY, 27 JANUARY 2021 11:00 A.M.–1:00 P.M. EST 17:00–19:00 CET COMMEMORATION CEREMONY Ms. Melissa FLEMING Under-Secretary-General for Global Communications MASTER OF CEREMONIES Mr. António GUTERRES United Nations Secretary-General H.E. Mr. Volkan BOZKIR President of the 75th session of the United Nations General Assembly Ms. Audrey AZOULAY Director-General of UNESCO Ms. Sarah NEMTANU and Ms. Deborah NEMTANU Violinists | “Sorrow” by Béla Bartók (1945-1981), performed from the crypt of the Mémorial de la Shoah, Paris. H.E. Ms. Angela MERKEL Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany KEYNOTE SPEAKER Hon. Irwin COTLER Special Envoy on Preserving Holocaust Remembrance and Combatting Antisemitism, Canada H.E. Mr. Gilad MENASHE ERDAN Permanent Representative of Israel to the United Nations H.E. Mr. Richard M. MILLS, Jr. Acting Representative of the United States to the United Nations Recitation of Memorial Prayers Cantor JULIA CADRAIN, Central Synagogue in New York El Male Rachamim and Kaddish Dr. Irene BUTTER and Ms. Shireen NASSAR Holocaust Survivor and Granddaughter in conversation with Ms. Clarissa WARD CNN’s Chief International Correspondent 2 Respondents to the question, “Why do you feel that learning about the Holocaust is important, and why should future generations know about it?” Mr. Piotr CYWINSKI, Poland Mr. Mark MASEKO, Zambia Professor Debórah DWORK, United States Professor Salah AL JABERY, Iraq Professor Yehuda BAUER, Israel Ms. -

Wanting, Not Waiting

WINNERSdateline OF THE OVERSEAS PRESS CLUB AWARDS 2011 Wanting, Not Waiting 2012 Another Year of Uprisings SPECIAL EDITION dateline 2012 1 letter from the president ne year ago, at our last OPC Awards gala, paying tribute to two of our most courageous fallen heroes, I hardly imagined that I would be standing in the same position again with the identical burden. While last year, we faced the sad task of recognizing the lives and careers of two Oincomparable photographers, Tim Hetherington and Chris Hondros, this year our attention turns to two writers — The New York Times’ Anthony Shadid and Marie Colvin of The Sunday Times of London. While our focus then was on the horrors of Gadhafi’s Libya, it is now the Syria of Bashar al- Assad. All four of these giants of our profession gave their lives in the service of an ideal and a mission that we consider so vital to our way of life — a full, complete and objective understanding of a world that is so all too often contemptuous or ignorant of these values. Theirs are the same talents and accomplishments to which we pay tribute in each of our awards tonight — and that the Overseas Press Club represents every day throughout the year. For our mission, like theirs, does not stop as we file from this room. The OPC has moved resolutely into the digital age but our winners and their skills remain grounded in the most fundamental tenets expressed through words and pictures — unwavering objectivity, unceasing curiosity, vivid story- telling, thought-provoking commentary. -

Caribbean Theatre: a PostColonial Story

CARIBBEAN THEATRE: A POSTCOLONIAL STORY Edward Baugh I am going to speak about Caribbean theatre and drama in English, which are also called West Indian theatre and West Indian drama. The story is one of how theatre in the English‐speaking Caribbean developed out of a colonial situation, to cater more and more relevantly to native Caribbean society, and how that change of focus inevitably brought with it the writing of plays that address Caribbean concerns, and do that so well that they can command admiring attention from audiences outside the Caribbean. I shall begin by taking up Ms [Chihoko] Matsuda’s suggestion that I say something about my own involvement in theatre, which happened a long time ago. It occurs to me now that my story may help to illustrate how Caribbean theatre has changed over the years and, in the process, involved the emergence of Caribbean drama. Theatre was my hobby from early, and I was actively involved in it from the mid‐Nineteen Fifties until the early Nineteen Seventies. It was never likely to be more than a hobby. There has never been a professional theatre in the Caribbean, from which one could make a living, so the thought never entered my mind. And when I stopped being actively involved in theatre, forty years ago, it was because the demands of my job, coinciding with the demands of raising a family, severely curtailed the time I had for stage work, especially for rehearsals. When I was actively involved in theatre, it was mainly as an actor, although I also did some Baugh playing Polonius in Hamlet (1967) ― 3 ― directing. -

British Television's Lost New Wave Moment: Single Drama and Race

British Television’s Lost New Wave Moment: Single Drama and Race Eleni Liarou Abstract: The article argues that the working-class realism of post-WWII British television single drama is neither as English nor as white as is often implied. The surviving audiovisual material and written sources (reviews, publicity material, biographies of television writers and directors) reveal ITV’s dynamic role in offering a range of views and representations of Britain’s black population and their multi-layered relationship with white working-class cultures. By examining this neglected history of postwar British drama, this article argues for more inclusive historiographies of British television and sheds light on the dynamism and diversity of British television culture. Keywords: TV drama; working-class realism; new wave; representations of race and immigration; TV historiography; ITV history Television scholars have typically seen British television’s late- 1950s/early-1960s single drama, and particularly ITV’s Armchair Theatre strand, as a manifestation of the postwar new wave preoccupation with the English regional working class (Laing 1986; Cooke 2003; Rolinson 2011). This article argues that the working- class realism of this drama strand is neither as English nor as white as is often implied. The surviving audiovisual material and written sources – including programme listings, reviews, scripts, publicity material, biographies of television writers and directors – reveal ITV’s dynamic role in offering a range of representations of Britain’s black population and its relationship to white working-class cultures. More Journal of British Cinema and Television 9.4 (2012): 612–627 DOI: 10.3366/jbctv.2012.0108 © Edinburgh University Press www.eupjournals.com/jbctv 612 British Television’s Lost New Wave Moment particularly, the study of ITV’s single drama about black immigration in this period raises important questions which lie at the heart of postwar debates on commercial television’s lack of commitment to its public service remit. -

Revista 29 Índice

REVISTA HISPANO CUBANA Nº 29 Otoño 2007 Madrid Octubre-Diciembre 2007 REVISTA HISPANO CUBANA HC DIRECTOR Javier Martínez-Corbalán REDACCIÓN Orlando Fondevila Begoña Martínez CONSEJO EDITORIAL Cristina Álvarez Barthe, Elías Amor, Luis Arranz, Mª Elena Cruz Varela, Jorge Dávila, Manuel Díaz Martínez, Ángel Esteban del Campo, Roberto Fandiño, Alina Fernández, Mª Victoria Fernández- Ávila, Celia Ferrero, Carlos Franqui, José Luis González Quirós, Mario Guillot, Guillermo Gortázar, Jesús Huerta de Soto, Felipe Lázaro, Jacobo Machover, José Mª Marco, Julio San Francisco, Juan Morán, Eusebio Mujal-León, Fabio Murrieta, José Luis Prieto Bena- vent, Tania Quintero, Alberto Recarte, Raúl Rivero, Ángel Rodríguez Abad, José Antonio San Gil, José Sanmartín, Pío Serrano, Daniel Silva, Álvaro Vargas Llosa, Alejo Vidal-Quadras. Esta revista es miembro de ARCE Asociación de Revistas Culturales de España Esta revista es miembro de la Federación Iberoamericana de Revistas Culturales (FIRC) Esta revista ha recibido una ayuda de la Dirección General del Libro, Archivos y Bibliotecas para su difusión en bibliotecas, centros culturales y universidades de España. EDITA, F. H. C. C/ORFILA, 8, 1ºA - 28010 MADRID Tel: 91 319 63 13/319 70 48 Fax: 91 319 70 08 e-mail: [email protected] http://www.revistahc.org Suscripciones: España: 24 Euros al año. Otros países: 60 Euros al año, incluído correo aéreo. Precio ejemplar: España 8 Euros. Los artículos publicados en esta revista, expresan las opiniones y criterios de sus autores, sin que necesariamente sean atribuibles a la Revista Hispano Cubana HC. EDICIÓN Y MAQUETACIÓN, Visión Gráfica DISEÑO, C&M FOTOMECÁNICA E IMPRESIÓN, Campillo Nevado, S.A. ISSN: 1139-0883 DEPÓSITO LEGAL: M-21731-1998 SUMARIO EDITORIAL CRÓNICAS DESDE CUBA -2007: Verano de fuego Félix Bonne Carcassés 7 -La ventana indiscreta Rafael Ferro Salas 10 -Eleanora Rafael Ferro Salas 11 -El Gatopardo cubano Félix Bonne Carcassés 14 DOSSIER: EL PRESIDIO POLÍTICO CUBANO -La infamia continua y silenciada. -

A Study of the Royal Court Young Peoples’ Theatre and Its Development Into the Young Writers’ Programme

Building the Engine Room: A Study of the Royal Court Young Peoples’ Theatre and its Development into the Young Writers’ Programme N O Holden Doctor of Philosophy 2018 Building the Engine Room: A Study of the Royal Court’s Young Peoples’ Theatre and its Development into the Young Writers’ Programme Nicholas Oliver Holden, MA, AKC A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Lincoln for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Fine and Performing Arts College of Arts March 2018 2 DECLARATION I declare that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in substantially the same form for a higher degree elsewhere. 3 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisors: Dr Jacqueline Bolton and Dr James Hudson, who have been there with advice even before this PhD began. I am forever grateful for your support, feedback, knowledge and guidance not just as my PhD supervisors, but as colleagues and, now, friends. Heartfelt thanks to my Director of Studies, Professor Mark O’Thomas, who has been a constant source of support and encouragement from my years as an undergraduate student to now as an early career academic. To Professor Dominic Symonds, who took on the role of my Director of Studies in the final year; thank you for being so generous with your thoughts and extensive knowledge, and for helping to bring new perspectives to my work. My gratitude also to the University of Lincoln and the School of Fine and Performing Arts for their generous studentship, without which this PhD would not have been possible. -

Download This Issue As A

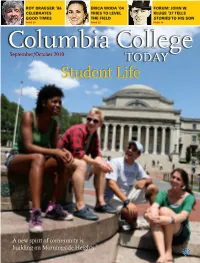

ROY BRAEGER ‘86 Erica Woda ’04 FORUM: JOHN W. CELEBRATES Tries TO LEVel KLUGE ’37 TELLS GOOD TIMES THE FIELD STORIES TO HIS SON Page 59 Page 22 Page 24 Columbia College September/October 2010 TODAY Student Life A new spirit of community is building on Morningside Heights ’ll meet you for a I drink at the club...” Meet. Dine. Play. Take a seat at the newly renovated bar grill or fine dining room. See how membership in the Columbia Club could fit into your life. For more information or to apply, visit www.columbiaclub.org or call (212) 719-0380. The Columbia University Club of New York 15 West 43 St. New York, N Y 10036 Columbia’s SocialIntellectualCulturalRecreationalProfessional Resource in Midtown. Columbia College Today Contents 24 14 68 31 12 22 COVER STORY ALUMNI NEWS DEPARTMENTS 30 2 S TUDENT LIFE : A NEW B OOK sh E L F LETTER S TO T H E 14 Featured: David Rakoff ’86 EDITOR S PIRIT OF COMMUNITY ON defends pessimism but avoids 3 WIT H IN T H E FA MI L Y M ORNING S IDE HEIG H T S memoirism in his new collec- tion of humorous short stories, 4 AROUND T H E QU A D S Satisfaction with campus life is on the rise, and here Half Empty: WARNING!!! No 4 are some of the reasons why. Inspirational Life Lessons Will Be Homecoming 2010 Found In These Pages. 5 By David McKay Wilson Michael B. Rothfeld ’69 To Receive 32 O BITU A RIE S Hamilton Medal 34 Dr. -

Cuba Page 1 of 22

Cuba Page 1 of 22 Cuba Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2001 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor March 4, 2002 Cuba is a totalitarian state controlled by President Fidel Castro, who is Chief of State, Head of Government, First Secretary of the Communist Party, and commander-in-chief of the armed forces. President Castro exercises control over all aspects of life through the Communist Party and its affiliated mass organizations, the government bureaucracy headed by the Council of State, and the state security apparatus. The Communist Party is the only legal political entity, and President Castro personally chooses the membership of the Politburo, the select group that heads the party. There are no contested elections for the 601-member National Assembly of People's Power (ANPP), which meets twice a year for a few days to rubber stamp decisions and policies previously decided by the governing Council of State. The Communist Party controls all government positions, including judicial offices. The judiciary is completely subordinate to the Government and to the Communist Party. The Ministry of Interior is the principal entity of state security and totalitarian control. Officers of the Revolutionary Armed Forces (FAR), which are led by Raul Castro, the President's brother, have been assigned to the majority of key positions in the Ministry of Interior in the past several years. In addition to the routine law enforcement functions of regulating migration and controlling the Border Guard and the regular police forces, the Interior Ministry's Department of State Security investigates and actively suppresses political opposition and dissent. -

WRAP THESIS Johnson1 2001.Pdf

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/3070 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. David Johnson Total Number of Pages = 420 The History, Theatrical Performance Work and Achievements of Talawa Theatre Company 1986-2001 Volume I of 11 By David Vivian Johnson A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in British and Comparative Cultural Studies University of Warwick, Centre for British and Comparative Cultural Studies May 2001 Table of Contents VOLUMEI 1. Chapter One Introduction 1-24 ..................................................... 2. Chapter Two Theatrical Roots 25-59 ................................................ 3. ChapterThree History Talawa, 60-93 of ............................................. 4. ChapterFour CaribbeanPlays 94-192 ............................................... VOLUME 11 5. ChapterFive AmericanPlaYs 193-268 ................................................ 6. ChapterSix English Plays 269-337 ................................................... 7. ChapterSeven Conclusion 338-350 ..................................................... Appendix I David Johnsontalks to.Yv6nne Brewster Louise -

God's Own Country

Fernsehen 14 Tage TV-Programm 12. bis 25.7.2018 Ab dem 19. Juli queere Filmreihe beim rbb God’s Own Country Alexandria Goliath Ein Feature beim Kulturradio sucht die Billy Bob Thorntons geniale Anwaltsserie alte Hauptstadt Ägyptens in der 2. Staffel bei Prime Tip1518_001 1 28.06.18 17:05 FERNSEHEN 12.7. – 25.7. TELEVISOR Neumann zum Zweiten VON LUTZ GÖLLNER Claudia Neumann, das gebe ich zu, hat eine Stimme, die nur die ei- gene Mutter lieben kann. Und sie neigt im Eifer des Gefechtes zu – nasagenwirmal – nicht ganz astrei- nen Metaphern. Doch genau damit steht sie unter den ZDF-Fußball- kommentatoren nicht alleine. Ihr RBB / AGATHA A. NITECKE / EDITION SALZGEBER Kollege Béla Réthy etwa ist so eine FOTO Lachnummer, dass sich inzwi- In windumtoster Landschaft sind Johnnys Ohren (Josh O‘Connor, Foto, re.) nicht hilfreich MERIE WALLACE AMAZON.COM / 2017 INC. OR ITS AFFILIATES / PRIME VIDEO schen sogar die eigene Sportre- FOTO daktion mit der Aktion „Be Bela“ QUEERE FILMREIHE IM RBB über ihn lustig macht. Doch über Neumann wird bei je- dem noch so kleinen Fehler die Häme gleich kübelweise ausge- Gelungene Auswahl schüttet. Und das – das ist ganz klar – weil sie eine Frau ist. Schon Der rbb präsentiert schwul-lesbische Filme angenehm klischeefreie vor zwei Jahren, als sie als erste Frau das Spiel einer Fußball-Euro- ls ein an die großstädtische Vielfalt Sozialdrama um eine Frage: Wie will ich pameisterschaft kommentieren Agewöhnter Kinofan mag man ei- leben und wie komme ich da hin? durfte, war das Ausmaß an Hass nen anderen Eindruck haben – doch Ge- In „Stadt Land Fluss“, einem Film, der von und Unflätigkeiten groß. -

Steps1 Revised

1999 Steps to Freedom A comparative analysis of civic resistance actions in Cuba between February 1999 and January 2000 First Edition: October 2000 Design and Editing: Janisset Rivero-Gutiérrez, Orlando Gutiérrez, Omar López Montenegro and Marilú Del Toro. Copyright 2000 by the Directorio Revolucionario Democrático Cubano. All Rights Reserved. Photo on the cover: December 17, 1999, Carlos Oquendo, Marcel Valenzuela, José Aguilar, and Diosdado Marrero (from left to right) leading a procession to the shrine of San Lázaro. The four men chained themselves together, wearing T-shirts with the photographs and names of political prisoners and carrying copies of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. When confronted by plainclothes political police, the protesters threw themselves on the ground and shouted, “Freedom for political prisoners!” They were kicked, beaten, and forcibly taken away in an unmarked car. Steps 3 • Carried out 227 nonviolent civic actions... • Held the 40-day Life and Freedom Fast in which a daily average of 217 Cubans throughout the country participated... • Founded 12 new independent libraries, bringing the total to 33 independent libraries throughout Cuba... • Expanded activities to all 14 provinces of the country and to the municipality of the Isle of Pines... • Founded two schools to teach civic nonviolent struggle... • Promoted important social projects such as cooperatives of independent farmers, distribution of toys to children, and distribution of food to the population... • On at least seven occasions, helped to Reynaldo Gómez González is arrested after impede police abuse of civilians or force confronting government-organized the state bureaucracy to comply with its mobs during a protest march promises of distributing food to the in Havana’s Dolores Park. -

Black British Plays Post World War II -1970S by Professor Colin

Black British Plays Post World War II -1970s By Professor Colin Chambers Britain’s postwar decline as an imperial power was accompanied by an invited but unprecedented influx of peoples from the colonized countries who found the ‘Mother Country’ less than welcoming and far from the image which had featured in their upbringing and expectation. For those who joined the small but growing black theatre community in Britain, the struggle to create space for, and to voice, their own aspirations and views of themselves and the world was symptomatic of a wider struggle for national independence and dignified personal survival. While radio provided a haven, exploiting the fact that the black body was hidden from view, and amateur or semi-professional club theatres, such as Unity or Bolton’s, offered a few openings, access to the professional stage was severely restricted, as it was to television and film. The African-American presence in successful West End productions such as Anna Lucasta provided inspiration, but also caused frustration when jobs went to Americans. Inexperience was a major issue - opportunities were scarce and roles often demeaning. Following the demise of Robert Adams’s wartime Negro Repertory Theatre, several attempts were made over the next three decades to rectify the situation in a desire to learn and practice the craft. The first postwar steps were taken during the 1948 run of Anna Lucasta when the existence of a group of black British understudies allowed them time to work together. Heeding a call from the multi-talented Trinidadian Edric Connor, they formed the Negro Theatre Company to mount their own productions and try-outs, such as the programme of variety and dramatic items called Something Different directed by Pauline Henriques.