Italy's Calciopoli Scandal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Graham Budd Auctions Sotheby's 34-35 New Bond Street Sporting Memorabilia London W1A 2AA United Kingdom Started 22 May 2014 10:00 BST

Graham Budd Auctions Sotheby's 34-35 New Bond Street Sporting Memorabilia London W1A 2AA United Kingdom Started 22 May 2014 10:00 BST Lot Description An 1896 Athens Olympic Games participation medal, in bronze, designed by N Lytras, struck by Honto-Poulus, the obverse with Nike 1 seated holding a laurel wreath over a phoenix emerging from the flames, the Acropolis beyond, the reverse with a Greek inscription within a wreath A Greek memorial medal to Charilaos Trikoupis dated 1896,in silver with portrait to obverse, with medal ribbonCharilaos Trikoupis was a 2 member of the Greek Government and prominent in a group of politicians who were resoundingly opposed to the revival of the Olympic Games in 1896. Instead of an a ...[more] 3 Spyridis (G.) La Panorama Illustre des Jeux Olympiques 1896,French language, published in Paris & Athens, paper wrappers, rare A rare gilt-bronze version of the 1900 Paris Olympic Games plaquette struck in conjunction with the Paris 1900 Exposition 4 Universelle,the obverse with a triumphant classical athlete, the reverse inscribed EDUCATION PHYSIQUE, OFFERT PAR LE MINISTRE, in original velvet lined red case, with identical ...[more] A 1904 St Louis Olympic Games athlete's participation medal,without any traces of loop at top edge, as presented to the athletes, by 5 Dieges & Clust, New York, the obverse with a naked athlete, the reverse with an eleven line legend, and the shields of St Louis, France & USA on a background of ivy l ...[more] A complete set of four participation medals for the 1908 London Olympic -

Procuratore Federale, 1 Luglio 2011 009 /1302Pf09-1 O

1 luglio 2011 009 /1302pf09-1 O/SP/blp " Procuratore Federale, letti gli atti e la relazione depositati nel fascicolo del procedimento n. 1302 pf 2009/2010, osserva quanto segue. 1. In via preliminare va precisato che con il presente atto, per owi motivi di economia procedimentale, ci si riporta, per quanto attiene all'indagine espletata e agli atti acquisiti, alla relazione richiamata e all'errata corrige allegata che, quindi, in ogni loro parte, formano parte integrante di questo provvedimento unitamente a tutti gli atti di indagine richiamati o, comunque, rilevanti. " presente procedimento è stato instaurato in data 10 aprile 2010, in relazione ad alcuni articoli di stampa nei quali si faceva riferimento alla circostanza che, nell'ambito dell'istruttoria dibattimentale già allora in corso di svolgimento presso l'A.G.O. di Napoli, concernente la vicenda comunemente nota come "calciopoli", stessero emergendo altre intercettazioni che riguardavano soggetti diversi e che presentavano elementi di novità rispetto al materiale probatorio che aveva formato oggetto dei procedimenti già celebratisi innanzi agli organi della giustizia sportiva. Veniva, quindi, inoltrata, in data 21 aprile 2010, specifica richiesta di acquisizione di atti processuali al Presidente della IX Sezione del Tribunale Ordinario di Napoli, in relazione alla quale, in data 19 ottobre 2010, veniva autorizzata la consegna di copia degli agli atti a questo Ufficio di Procura. La documentazione in questione, contenuta in un CO e materialmente acquisita dal Procuratore federale in data 25 ottobre 2010, era da considerarsi, tuttavia, parziale, come emerge dagli atti di acquisizione della documentazione formata in sede penale, specificamente indicati nella relazione allegata, alla quale si fa rinvio, unitamente alla documentazione di cui al punto 3, lettere da a) ad I) , dell'indice degli atti del fascicolo. -

From Comparative Analysis to Final Publication: Nationalism and Globalization in English and Italian Football Since 1930

From Comparative Analysis to Final Publication: Nationalism and Globalization in English and Italian Football Since 1930 Penn, R. (2018). From Comparative Analysis to Final Publication: Nationalism and Globalization in English and Italian Football Since 1930. Sage Research Methods Cases, Part 2. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526445308 Published in: Sage Research Methods Cases Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights © 2018 Sage Publications. This work is made available online in accordance with the publisher’s policies. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:02. Oct. 2021 From Comparative Analysis to Final Publication: Nationalism and Globalization in English and Italian Football Since 1930 Contributors: Roger Penn Pub. Date: 2018 Access Date: March 21, 2018 Academic Level: Postgraduate Publishing Company: SAGE Publications Ltd City: London Online ISBN: 9781526445308 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781526445308 ©2018 SAGE Publications Ltd. -

La Piramide Del Calcio Italiano

LA PIRAMIDE DEL CALCIO ITALIANO Dal 1898 Dal 1904 Dal 1906 Dal 1912-13 Dal 1922-23 al 1903 al 1905 al 1911-12 al 1920-21 al 1925-26 1° Livello I Categoria I Categoria I Categoria I Categoria I Divisione 2° Livello === II Categoria II Categoria Promozione II Divisione 3° Livello === === III Categoria III Categoria III Divisione 4° Livello === === === === IV Divisione N.B.: Campionati sospesi dal 1915 al 1919 per la Prima Guerra Mondiale. Nel 1921-22 si verifica una scissione in due diverse federazioni che organizzano campionati autonomi strutturati su tre livelli (I,II, III Divisione nella Confederazione Calcistica Italiana e I Categoria, Promozione, III Categoria nella Federazione Italiana Giuoco Calcio). Dal 1926-27 Dal 1929-30 Dal 1935-36 Dal 1948-49 1928-29 al 1927-28 al 1934-35 al 1947-48 al 1951-52 1° Livello Div.Nazionale Div.Nazionale Serie A Serie A Serie A 2° Livello I Divisione I Divisione Serie B Serie B Serie B 3° Livello II Divisione II Divisione I Divisione Serie C Serie C 4° Livello III Divisione III Divisione II Divisione I Divisione Promoz.Int. 5° Livello IV Divisione === III Divisione II Divisione I Divisione 6° Livello === === === === II Divisione 7° Livello === === === === === N.B.: Campionati sospesi dal 1943 al 1945 per la Seconda Guerra Mondiale. Nel 1945-46 vengono organizzati dei campionati misti (Serie A a due gironi, campionato misto di Serie B-C ecc.). Dal 1952-53 Dal 1959-60 Dal 1968-69 1957-58 1958-59 al 1956-57 al 1967-68 al 1977-78 1° Livello Serie A Serie A Serie A Serie A Serie A 2° Livello Serie B Serie B Serie B Serie B Serie B 3° Livello Serie C Serie C Serie C Serie C Serie C 4° Livello IV Serie Interreg. -

A TRE MESI DI DISTANZA DALLO SCUDETTO, IL DELFINO PESCARA SI RIPETE in SUPERCOPPA: Foto Paolo Cassella/Divisione Calcio a Cinque GOLOSO ASTI KO 7-4

MAGAZINE A TRE MESI DI DISTANZA DALLO SCUDETTO, IL DELFINO PESCARA SI RIPETE IN SUPERCOPPA: Foto Paolo Cassella/Divisione Calcio a cinque GOLOSO ASTI KO 7-4 NUMERO 1 // STAGIONE 2015/16 SETTIMANALE GRATUITO SUL FUTSAL LAZIALE E NAZIONALE // ROMA SCARICA L’APP Ora inserisci il codice in promozione: C A LC IO A 5 LI VE e con soli 4,80 € in più per te una Sim Beactive Mobile con Calcio A5 Live Magazine - Anno IX Stagione 2015/2016 N°1 del 17/09/2015 - Editore: Calcio A5 Live S.r.l. Redazione: Via Trento, 44/A - Ciampino (RM) - Tel. 348 3619155 1 Giga di traffico dati e Direttore responsabile: Francesco Puma - DISTRIBUZIONE GRATUITA email: [email protected] - STAMPA ARTI GRAFICHE ROMA - Via Antonio Meucci, 27 - Guidonia (RM) - registrato presso il tribunale 400 minu17/09/2015ti di chiamate inclusi 1 di Velletri il 25/10/2007 - registrazione N° 25/07 Eco.TecH Tecnologie per l’Uomo Flood Light Batten Light LED 150 W LED 54 W Eco.TecH Tecnologie per l’Uomo Flood Light Batten Light LED 150 W LED 54 W SEGUICI SU EDITORIALE MAGAZINE A TRE MESI DI DISTANZA DALLO SCUDETTO, IL DELFINO PESCARA SI RIPETE IN SUPERCOPPA: Foto Paolo Cassella/Divisione Calcio a cinque GOLOSO ASTI KO 7-4 NUMERO 1 // STAGIONE 2015/16 SETTIMANALE GRATUITO SUL FUTSAL LAZIALE E NAZIONALE // ROMA SCARICA L’APP Ora inserisci il codice in promozione: C A LC IO A 5 LI VE e con soli 4,80 € in più per te una Sim Beactive Mobile con Calcio A5 Live Magazine - Anno IX Stagione 2015/2016 N°1 del 17/09/2015 - Editore: Calcio A5 Live S.r.l. -

30 06 2019 Annual Financial Report

30 06 2019 ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT 30 06 2019 REGISTERED OFFICE Via Druento 175, 10151 Turin Contact Center 899.999.897 Fax +39 011 51 19 214 SHARE CAPITAL FULLY PAID € 8,182,133.28 REGISTERED IN THE COMPANIES REGISTER Under no. 00470470014 - REA no. 394963 CONTENTS REPORT ON OPERATIONS 6 Board of Directors, Board of Statutory Auditors and Independent Auditors 9 Company Profile 10 Corporate Governance Report and Remuneration Report 17 Main risks and uncertainties to which Juventus is exposed 18 Significant events in the 2018/2019 financial year 22 Review of results for the 2018/2019 financial year 25 Significant events after 30 June 2019 30 Business outlook 32 Human resources and organisation 33 Responsible and sustainable approach: sustainability report 35 Other information 36 Proposal to approve the financial statements and cover losses for the year 37 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS AT 30 JUNE 2019 38 Statement of financial position 40 Income statement 43 Statement of comprehensive income 43 Statement of changes in shareholders’ equity 44 Statement of cash flows 45 Notes to the financial statements 48 ATTESTATION PURSUANT TO ARTICLE 154-BIS OF LEGISLATIVE DECREE 58/98 103 BOARD OF STATUTORY AUDITORS’ REPORT 106 INDEPENDENT AUDITORS’ REPORT 118 ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT AT 30 06 19 5 REPORT ON OPERATIONS BOARD OF DIRECTORS, BOARD OF STATUTORY AUDITORS AND INDEPENDENT AUDITORS BOARD OF DIRECTORS CHAIRMAN Andrea Agnelli VICE CHAIRMAN Pavel Nedved NON INDEPENDENT DIRECTORS Maurizio Arrivabene Francesco Roncaglio Enrico Vellano INDEPENDENT DIRECTORS Paolo Garimberti Assia Grazioli Venier Caitlin Mary Hughes Daniela Marilungo REMUNERATION AND APPOINTMENTS COMMITTEE Paolo Garimberti (Chairman), Assia Grazioli Venier e Caitlin Mary Hughes CONTROL AND RISK COMMITTEE Daniela Marilungo (Chairman), Paolo Garimberti e Caitlin Mary Hughes BOARD OF STATUTORY AUDITORS CHAIRMAN Paolo Piccatti AUDITORS Silvia Lirici Nicoletta Paracchini DEPUTY AUDITORS Roberto Petrignani Lorenzo Jona Celesia INDEPENDENT AUDITORS EY S.p.A. -

P19 Layout 1

SPORTS MONDAY, OCTOBER 28, 2013 Neymar outshines Bale in battle of big-money buys BARCELONA: Gareth Bale was given his chance to that every player wants to play in.” The contrast on the pitch, overshadowing the world’s best in been all bad news for Bale, though. He scored his shine on the biggest stage of all on Saturday as he between the summer’s blockbuster signings couldn’t Lionel Messi and Cristiano Ronaldo. only Real goal to date on his debut against Villarreal. made his El Clasico debut for Real Madrid against have been greater and merely summed up the differ- His goal may only have been his fourth in 14 However, since then a series of niggling injuries Barcelona on Saturday. ence in how they have adapted to La Liga in their appearances, but his through ball from which have hampered his participation and he is still to play However, unfortunately for the Welshman, it was first two months in Spain. Sanchez finished the contest with a nonchalant lob a full 90 minutes in any of his six appearances. Bale another expensive import making his bow in the fix- Neymar has benefited massively from the relative- over Lopez was already his seventh assist, making was defended by his own boss Carlo Ancelotti after ture who shone, as Neymar scored Barca’s opener ly swift process that saw his 57 million euro ($78.1 him the chief goal creator in a side boasting the tal- the game, the Italian making the wholly reasonable and then teed up Alexis Sanchez to make the game million, £48.3 million) move from Santos completed ents of Andres Iniesta, Xavi and Cesc Fabregas. -

Il Libro Marrone Dell'accusa

2 Il libro marrone dell’accusa – www.giulemanidallajuve.com 3 Sommario Sommario ______________________________________________________________ 3 Prefazione ______________________________________________________________ 6 20 gennaio 2009 _________________________________________________________ 9 24 marzo 2009 __________________________________________________________ 9 21 aprile 2009 __________________________________________________________ 10 5 maggio 2009 _________________________________________________________ 14 15 maggio 2009 ________________________________________________________ 19 19 maggio 2009 ________________________________________________________ 23 Romeo Paparesta ____________________________________________________ 23 26 maggio 2009 ________________________________________________________ 27 Giuseppe Gazzoni Frascara _____________________________________________ 29 Danilo Nucini _______________________________________________________ 35 16 giugno 2009 _________________________________________________________ 45 Gianluca Paparesta ___________________________________________________ 45 Dario Canovi ________________________________________________________ 49 Aniello Aliberti ______________________________________________________ 53 30 giugno 2009 _________________________________________________________ 56 Teodosio De Cillis ____________________________________________________ 56 Giancarlo Bertolini ___________________________________________________ 61 Dario Galati ________________________________________________________ -

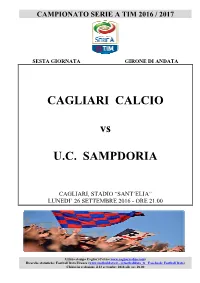

Cagliari-Sampdoria

CAMPIONATO SERIE A TIM 2016 / 2017 SESTA GIORNATA GIRONE DI ANDATA CAGLIARI CALCIO vs U.C. SAMPDORIA CAGLIARI, STADIO “SANT’ELIA” LUNEDI’ 26 SETTEMBRE 2016 - ORE 21.00 Ufficio stampa Cagliari Calcio ( www.cagliaricalcio.com ) Ricerche statistiche: Football Data Firenze ( www.footballdata.it - @footballdata_fi – Facebook: Football Data ) Chiuso in redazione il 23 settembre 2016 alle ore 20.00 SESTA GIORNATA GIRONE DI ANDATA Sabato 24 settembre ore 18.00 Palermo Juventus Sabato 24 settembre ore 20.45 Napoli ChievoVerona Domenica 25 settembre ore 12.30 Torino Roma Domenica 25 settembre ore 15.00 Genoa Pescara Domenica 25 settembre ore 15.00 Inter Bologna Domenica 25 settembre ore 15.00 Lazio Empoli Domenica 25 settembre ore 15.00 Sassuolo Udinese Domenica 25 settembre ore 20.45 Fiorentina Milan Lunedì 26 settembre ore 19.00 Crotone Atalanta Lunedì 26 settembre ore 21.00 Cagliari Sampdoria PROSSIMO TURNO Sabato 1 ottobre ore 18.00 Pescara ChievoVerona Sabato 1 ottobre ore 20.45 Udinese Lazio Domenica 2 ottobre ore 12.30 Empoli Juventus Domenica 2 ottobre ore 15.00 Atalanta Napoli Domenica 2 ottobre ore 15.00 Bologna Genoa Domenica 2 ottobre ore 15.00 Cagliari Crotone Domenica 2 ottobre ore 15.00 Sampdoria Palermo Domenica 2 ottobre ore 18.00 Milan Sassuolo Domenica 2 ottobre ore 18.00 Torino Fiorentina Domenica 2 ottobre ore 20.45 Roma Inter CLASSIFICA SERIE A TIM 2016 / 2017 BILANCIO TOTALE GARE IN CASA GARE FUORI CASA pos. club punti v n p gf gs v n p gf gs v n p gf gs 1 JUVENTUS 15 5 0 1 12 4 3 0 0 9 2 2 0 1 3 2 2 NAPOLI 14 4 2 0 14 5 -

Italian Serie 'A' Academy Training

This ebook has been licensed to: Gordon Ferguson ([email protected]) Italian Serie ‘A’ Academy Training An inside look at two Italian Professional Academies Free Email Newsletter at worldclasscoaching.com If you are not Gordon Ferguson please destroy this copy and contact WORLD CLASS COACHING. This ebook has been licensed to: Gordon Ferguson ([email protected]) Italian Serie ‘A’ Academy Training First published June, 2012 by WORLD CLASS COACHING 3404 W 122nd Terr Leawood, KS Copyright © WORLD CLASS COACHING 2012 All rights reserved. No parts of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher. Authors - Dave Brown Published by WORLD CLASS COACHING If you are not Gordon Ferguson please destroy this copy and contact WORLD CLASS COACHING. This ebook has been licensed to: Gordon Ferguson ([email protected]) Author Dave Brown Dave Brown is the Director of Coaching for the WFC Rangers premier youth club in Bellingham, WA. In addition to being a former high school, college and ODP coach, he has coached at the top youth level for over 20 years and was Washington State’s co-winningest coach for five years, winning several state championships. His former players have gone on to play professionally in the MLS and WUSA as well as earning U17, U20 and full US National team honors. He holds the USSF “B” National Coaching license and the Director of Coaching certificate from the NSCAA. He is the author of the Juventus Journal and has submitted several other reports from Italy including those observed at the Italian National Training Center in Coverciano. -

AGCM - Autorita' Garante Della Concorrenza E Del Mercato 22/09/2020 12:48

AGCM - Autorita' Garante della Concorrenza e del Mercato 22/09/2020 12:48 Follow us on ! (https://twitter.com/antitrust_it) " (https://www.facebook.com/agcm.it/) # (https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCYSdEdNwoDvmt4mKSDmUtjQ) $ (/en/) Search... Advanced search (http://en.agcm.it/en/search? searchword=) You are in: Home (/en) / Media (/en/media) / Press releases (/en/media/press-releases) / ICA, Napoli football club will reimburse the ticket, if so requested by consumer, in case of match postponement CV205 - ICA, Napoli football club will reimburse the ticket, if so requested by consumer, in case of match postponement PRESS RELEASE The Authority asked SSC Napoli S.p.A. to remove any possible unfair element of certain clauses in the contractual conditions of the Regulations of the San Paolo stadium and in the 2019-2020 Season Ticket Conditions The Autorità Garante della Concorrenza e del Mercato (Italian Competition Authority) closed the pre- investigation proceedings against the Serie A SSC Napoli football club following the removal by the abovementioned company of any possible unfair element of certain clauses contained in the contractual conditions of the "Regulations to use the San Paolo Stadium" and in the “2019-2020 Season Ticket Conditions" The examined clauses could be deemed unfair pursuant to articles 33 and 34 of the Consumer Code and lead to a signi!cant imbalance for consumers in the contractual services provided. Accepting the Authority’s request, SSC Napoli removed from article 12 of the Regulations to use the San Paolo Stadium" the clause excluding any type of liability of the club in the event of match postponement and expressly recognised the right of the fans to choose between attending the match on the new date and the reimbursement of the ticket. -

Jankovic Targets Top-10 Finish in 2017

SSHOOTINGHOOTING | Page 2 GOLF | Page 9 Nearly 300 Spieth rolls to shooters to gun four-stroke To Advertise here for glory at win at Pebble Call: 444 11 300, 444 66 621 Qatar Open Beach Tuesday, February 14, 2017 FOOTBALL Jumada I 17, 1438 AH Emery, PSG look GULF TIMES to get over Barcelona at last SPORT Page 3 TENNIS / QATAR TOTAL OPEN FOOTBALL Record numbers Jankovic targets to compete in top-10 fi nish in 2017 2017 Workers Cup Serbian makes it to main draw with a win over Tsvetana Pironkova Hassan al-Kuwari (left), executive director, Marketing and Communications at Qatar Stars League, and Fatma al-Nuaimi (right), director, Communications at Supreme Committee for Delivery & Legacy, address a press conference yesterday. By Sports Reporter Doha undreds of football-loving workers from across Qa- tar are set to compete in the Serbia’s Jelena Jankovic in action against Bulgaria’s Tsvetana Pironkova during their qualifying singles match at Khalifa International Tennis and Squash Complex fi fth edition of Doha’s an- Hnual Workers Cup, the much antici- in Doha yesterday. (Below) Madison Brengle of USA too made it to the main draw. PICTURES: Noushad Thekkayil pated seven-week football tournament By Sahan Bidappa organised by the Qatar Stars League Doha (QSL) and sponsored by the Supreme Committee for Delivery & Legacy (SC). This year’s tournament will see over aving plummeted to 50th in 600 players compete in 32 teams — an the world rankings, it almost increase on the 24 teams that battled feels unreal that Jelena Jank- it out for glory last year.