Labour Migration from (And In) Bihar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IN the HIGH COURT of JUDICATURE at PATNA (FROM RESIDENTIAL OFFICE VIA VIDEO APPLICATION) Criminal Writ Jurisdiction Case No.367 of 2020 Arising out of PS

IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUDICATURE AT PATNA (FROM RESIDENTIAL OFFICE VIA VIDEO APPLICATION) Criminal Writ Jurisdiction Case No.367 of 2020 Arising Out of PS. Case No.-158 Year-2020 Thana- NARPATGANJ District- Araria ====================================================== 1. MD. ENAMUL HASAN S/o Nazimuddin Resident of 137/Green Road Dhaka P.S-Sher e Bangle Nagar, Dhaka, country Bangladesh, Passport No. EF0146642. Presently residing at Hotel Basera, Ward No.24, P.S.-Araria, District-Araria. 2. Mahbubur Rahman S/o Abu Bakar Siddique R/o Masulia, P.S. and District- Habiganj, country Bangladesh, Passport No. BP0228387. Presently residing at Hotel Basera, Ward No.24, P.S-Araria, District-Araria. 3. Md. Almamun Sarkar @ Md. Al Mamun Sarker S/o Abdul Sattar R/o Akuwa Morolbari P.S.-Kotwali, District-Maymen Singh, Bangladesh, Passport No. EE0355730. Presently residing at Hotel Basera, Ward No.24, P.S-Araria, District-Araria. 4. Mohammad Motahar Hossen S/o Abdul Mutlif @ Abdul Motaleb R/o Akuwa Morolbari,P.S-Kotwali, District-Maymen Singh, Bangladesh, Passport No. BK0449940. Presently residing at Hotel Basera, Ward No.24, P.S-Araria, District-Araria. 5. Md. Afzal Hossain Rakib @ Afzal Hossain Rakib S/o Alak Chand @ Md. Alak Chan R/o Charkalibari, Ward No.32, P.S-Kotwali, District-Maymen Singh country Bangladesh, Passport No. EB0373547. Presently residing at Hotel Basera, Ward No.24, P.S-Araria, District-Araria. 6. Md. Mokammel Haque S/o Md. Sirajul Haque @ Md. Serajul Haque R/o Madan Babu Road, P.S-Kotwali, District-Maymen Singh, Country Bangladesh, Passport No. BN0433468 Presently residing at Hotel Basera, Ward No.24, P.S-Araria, District-Araria. -

Report on the Flood Relief Camps in Bihar

For a Morsel of Life! A ‘Dalit Watch’ Report on the Flood Relief Camps in Bihar September 2008 Based on Monitoring of 205 Relief Camps Located in the Districts of Supaul, Saharsa, Madhepura, Araria and Purnea Monitoring Undertaken by Volunteers and Members of Dalit Watch associated with Bachpan Bachao Andolan Badh Sukhad Mukti Andolan Dalit Samanvay Lokshakti Sangathan Nari Gunjan National Campaign for Dalit Human Rights and Praxis – Institute for Participatory Practices Report on the Flood Relief Camps in Bihar Key personnel involved in anchoring the monitoring exercise Abhay Kumar, Anindo Banerjee, Ashutosh Vishal, Bharat Kale, Chandra Bhushan, Devendra Kumar, Dr. SDJM Prasad, Kamal, Girish Chandra Mishra, Jay Kumar Verma, Mahendra Kumar Roshan, Mukta Ojha, Rambabu Kumar, Rahul Singh, Ranjeev, Sr. Sudha Verghese, Vijeta Laxmi Supervision of relief camps undertaken by Abhay Kumar, Amar Kumar Sada, Amarnath Kumar, Amitesh Kumar, Anil Kumar Singh, Anita Devi, Archana Kumari, Arun Kumar Paswan, Atul Priyadarsi, Azad Alam, Bharti, Bheekho Bodh, Bhugeshwar Ram, Bhuneshwar Naga, Birju Kumar, Chaube Bharti, Denish, Dilip Giri, Dinesh Kumar, Dr. Rampal Sharma, Dr. Shailendra Kumar, Gajender Majhi, Ganesh Paswan, Gautam Thakur, Gulabchand Sada, Jeevan Prakash Bharti, Kamal Kishor Bharti, Kamal Mahto, Kamlesh Kumar, Lalan Paswan, Lalan Ram, Laxman Sada, Laxmi Devi, Mahendra Kumar Roshan, Mala, Mamta Devi, Manju Devi, Manoj Kumar, Manoj Kumar, Md. Jawaluddin HaQ, Meera Devi, Moti Sada, Mukesh Kumar, Mumtaz Begum, Neelu Mala, Neeraj Kumar, Priyadarshi -

Download Book (PDF)

Wetland Ecosystem Series, 14 Faunal Diversity of Chaurs of North Bihar (Zooplankton, Molluscs, Pisces and Aves) (IBA-IN- BR-Ol) ZOOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA Wetland Ecosystem Series, l4 Faunal Diversity of Chaurs of North Bihar (Zooplankton, Molluscs, Pisces and Aves) (I BA-I N-BR-Ol) Edited by the Dira:t:or, Zoological Survey of India, Kolkata Zoological Survey of India Kolkata CITATION Editor- Director, 2011 Faunal Diva-sity of Chaurs of North Bihar (Zooplankton, Molluscs, PiscES and AVES). Wetland Ecosystffn Sa-iES, ]A: 1-113 + 7 platES (Published by the Director, Zool. Surv. India, Kolkata) Published: November, 2011 ISBN 978-81-8171-297-4 Coordinator Dr. Gopal Sharma Zoological Survey of I ndia, Gangetic Plains Regional Centre, Patna-16 © Govt. of India, 2011 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED • No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. • This book is sold subiect to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise disposed of without the publisher's consent, in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published. • The correct price of this publication is the price printed on this page. Any revised price indicated by a rubber stamp or by a sticker or by any other means is incorrect and should be unacceptable. PRICE India : ~ 450.00 Foreign: $ 30; £ 25 Published at the Publication Division by the Director, Zoological Survey of India, 234/4, A.J .c. -

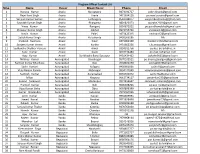

Sl.No Name and Address of Centre Name of District Name of the Counsellor Contact No Name of Medical Incharge/ ICTC Manager Contact No

Sl.No Name and address of Centre Name of District Name of the counsellor Contact No Name of Medical Incharge/ ICTC Manager Contact No Araria Ahmad Nadim Ahsan 9709576800 Dr. D.D.Singh, 9470003030, 1 SH, Araria District‐Araria, Pin Code‐854311 Dr. D.D.Singh, 9470003030, Araria 2 PPTCT, SH, Araria District‐Araria, Pin Code‐854311 Deepika Singh Sehgal 9430265287 Araria 3 Ref. Hos. Farbisganj District‐Araria, Pin Code‐ 854318 Umakant Sharma 9234269575, 9234532201 M.O‐Jay Narayan Prasad ,9470003033, Araria 4 Ref. Hos. Raniganj District‐Araria, Pin Code‐ 854334 Nagendra Prasad 9507788338 Dr. Abdhesh Kumar 9470003034, Araria 5 PHC Jokihaat District‐Araria, Pin Code‐854329 Pankaj Kumar 9771103971 M.D‐Siftain alam, Araria 6 PHC Kursakanta District‐Araria, Pin Code‐854331 Vacant Dr. Rajendra Kumar, Araria 7 PHC Narpatganj District‐Araria, Pin Code‐854335 NA NA Dr. Yogendra Pd. Singh, 9955275569 Araria 8 PHC Palasi District‐Araria, Pin Code‐854333 Amit Kumar 9470844168 Dr. Jahagir Alam 9470003037 Araria 9 PHC Sikati , Pin Code‐854333 Vacant ‐9430806886 Arwal NA NA Dr.Bindeshwari Sharma 9430059427 Centre Phone ‐ 06337‐229276, 10 Sadar Hospital, District‐ Arwal, Pin Code‐804401 Dr.Bindeshwari Sharma 9430059427 Centre Phone ‐ 06337‐229276, Arwal 11 PPTCT, Sadar Hospital, District‐ Arwal, Pin Code‐804401 Kavita Sinha 9576087610 Aurangabad Rakesh Kumar. Rai 9431429761 Dr. S.K. Aman, 9470003061 12 Sadar Hosp. Aurangabad District‐Aurangabad, Pin Code‐824102 PPTCT, Sadar Hosp. Aurangabad District‐Aurangabad, Pin Code‐ Aurangabad Anjani Kumari Dr. S.K. Aman, 9470003061, 13 824102 Banka Binod Kumar Yadav 9430611053 Dr. N.K.Vidyerthi 9470003073, 14 Sadar Hospital Banka District‐ Banka, Pin Code‐813102 Banka 15 PPTCT, Sadar Hospital Banka District‐ Banka, Pin Code‐813102 Dolly Kumari 9430966599 NA Sadar Hospital District‐Begusarai, Pin Code‐851101 Begusarai Santosh Kumar Sant 9430066712 A.K. -

Bihar State Highways Project Subproject: SH-77 (Kursela – Forbisgunj)

Resettlement Planning Document Resettlement Plan Document Stage: Updated Project Number: 41127 August 2008 IND: Bihar State Highways Project Subproject: SH-77 (Kursela – Forbisgunj) Prepared by Road Construction Department, Government of Bihar The resettlement plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. TABLE OF CONTENTS ITEM Page No. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 – 8 1. PROJECT DESCRIPTION 9 – 11 1.1 The Project 9 1.2 Subproject Background 9 1.3 Scope of Subproject Work 9 1.4 Minimization of Resettlement 10 1.5 Subproject Impacts and Benefits 10 1.6 Scope and Objective of Resettlement Plan (RP) 11 2. SCOPE OF LAND ACQUISITION AND RESETTLEMENT IMPACTS 12 – 16 2.1. Scope of Land Acquisition 12 2.2. Census Survey 12 2.3. Subproject Impacts 12 3. SOCIO ECONOMIC PROFILE 17 – 21 3.1 Socio-Economic Survey 17 3.2 Social Profile of APs 17 3.3 Socio-Economic Findings Based on Sample Survey 19 4. RESETTLEMENT POLICY AND LEGAL FRAMEWORK 22 – 26 4.1 Introduction 22 4.2 Existing Laws and Policies 22 4.3 Resettlement Principles for the Project 23 4.4 Valuation of Assets 24 4.5 Entitlement Matrix 25 4.6 Cut-off Date 26 5. PUBLIC CONSULTATION AND DISCLOSURE OF INFORMATION 27 – 30 5.1 Public Consultation in the Project 27 5.2 Major Findings of the Consultations 28 5.3 Plan for Further Consultation in the Project 29 5.4 Disclosure of RP 30 6. -

Mobile No. and E-Mail Address of Programme

Program Officer Contact List Slno. Name Descr Block Descr Phone Email 1 Hansraj Kumar Araria Narpatganj 9473191727 [email protected] 2 Rajni Kant Singh Araria Araria 9471634128 [email protected] 3 Sanjeev Kumar Suman Araria Forbesganj 8544188977 [email protected] 4 Saurabh Kumar Singh Araria Bhargama 9801823973 [email protected] 5 Vinay Kumar Araria Raniganj 9304872022 [email protected] 6 Shrawan Kumar Singh Araria Jokihat 9973755740 [email protected] 7 Navin Kumar Araria Palasi 9473423315 [email protected] 8 Satish Kumar Singh Araria Kursakanta 9430566186 NA 9 Shailesh Swaroop Arwal Kaler 9471002340 [email protected] 10 Sanjeev Kumar Verma Arwal Kurtha 9431863336 [email protected] 11 Sudhanshu Shekhar Pandey Arwal Arwal 9334912758 [email protected] 12 Sunil Kumar Arwal Karpi 9097774484 [email protected] 13 Ajay Kumar Arwal Sonbhadra Bansi Suryapur 9431434402 [email protected] 14 Nirbhay Kumar Aurangabad Daudnagar 9570103521 [email protected] 15 Santosh Kumar Bhardwaj Aurangabad Deo 7004802150 [email protected] 16 Sashi Kumari Aurangabad Rafiganj 9430905936 [email protected] 17 Vijay Ranjan Parmar Aurangabad Nabinagar 9934121049 [email protected] 18 Santosh Kumar Aurangabad Aurangabad 8092481072 [email protected] 19 Milan Aurangabad Haspura 9661734117 [email protected] 20 Kumari Saraswati Aurangabad Madanpur 9973454647 [email protected] 21 Pramod Kumar Aurangabad Goh 9006638226 [email protected] 22 Vijay Kumar Sinha Aurangabad Obra 9097893399 [email protected] -

Irrigation Planning and Command Area

CHAPTER –VII IRRIGATION PLANNING AND COMMAND AREA 7.0 General The Kosi-Mechi intrastate link envisages diversion of part of surplus water of Kosi river for extending irrigation in new command areas of Mahananda basin lying between river Parman and Mechi by extending the existing EKMC beyond its tail end at RD 41.30 km upto river Mechi. The link canal will utilize existing EKMC after its remodelling. The link canal beyond Parman river will provide irrigation in new command areas enroute of the link lying in Araria, Kishanganj, Purnea and Katihar districts of Bihar. 7.1 Existing /proposed irrigation status in enroute command As detailed in Chapter-V Hydrology, a 1149 m long Hanuman Nagar barrage was constructed near Hanuman Nagar town close to Indo- Nepal border with pond level of 74.69 m to enable to provide irrigation through the EKMC and WKMC off-taking from the head regulators situated at both ends of the barrage. The WKMC provides irrigation in Nepal and some parts in India, while the EKMC is aimed to provide irrigation in India in Katihar and Khagaria district situated in the Eastern side of the Kosi river and western side of the river Mahananda of north Bihar. GCA, CCA and annual irrigation as envisaged in the project report are given in Table 7.1. The above reported GCA and CCA were reassessed by a committee constituted by Govt. of Bihar under the chairmanship of the then State Minister of River Valley Projects Department in 1975. The committee observed that the GCA and CCA and annual irrigation were on higher side and not responding to the ground truth. -

Bihar Storm Assessment Report 2010

Joint Thematic Area Assessment Of Bihar Storm 2010 Bihar Inter Agency Group Secretariat ODRC Office, 21/A-1, Patliputra Colony, Patna- 800013 Tel:0612-2270399, Fax:0612-2270400 Supported by: Bihar IAG Assessment Report Bihar Storm 2010 Contents: 1. Executive Summary 2. Team/Facilitators /Govt Report 3. Summary Of Exhaustive Joint Thematic Area Assessment 4. Objective Of Assessment 5. Methodology 6. Activities/Summary Of Situation Assessment 7. Sector wise findings/ status I. Shelter II. Agriculture III. Water Sanitation and Hygiene/ IV. Health V. Nutrition VI. Education VII. Child Protection Bihar IAG Assessment Report Bihar Storm 2010 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: Pre – monsoon summer thunder storms are common in Bihar and are locally known as Kal Meagh ,or ‘mango showers’ as it brings devastation to the standing crops and Mango plantations. The Kal Meagh of 13th April 2010 was the most devastating that the elderly in the community can recall in the remote northeast Simanchal region of Bihar. According to the government reports the human death toll due the storm rose to ninety in the districts of Araria ,Purnea, Katihar, Supaul, and Kishangang . One Lakh Ninety Seven Thousand families houses were damaged or destroyed.. Although some of the affected families were quick to reconstruct their temporary shelters and there was no risk of morbidity or epidemics, it will still take time for the community to recover. The 125kms winds which lasted for thirty minutes, destroyed tens and thousands of hectares of standing crops of maize, sunflower and the cultivated crops of wheat. The government of Bihar was effective in relief response and it announced Rs. -

Araria Introduction

DISTRICT PROFILE ARARIA INTRODUCTION Araria, which was earlier a sub-division of Purina, became a full-fledged district on January 14, 1990, after the division of Purnia into three districts, namely Purnia, Araria and Kishanganj. This showery district of north-eastern Bihar is one of the most backward districts of Bihar, standing at the bottom of the 90 minority concentration districts. Borders of Araria are surrounded by Nepal in northern side, Kishanganj in eastern side and Supaul at western side. District border is adjacent to border of Nepal, so the district is important in terms of security. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND The territory of the present-day district became Araria sub-division of the erstwhile Purnia district in 1964. In ancient times Araria was ruled by three important clans of Indian history. The important tribe of Kiratas governed the northern side, while the eastern side was under the Pundras and area west of the river Kosi, at that time flowing somewhere near the present Araria, by Angas. During the Mauryan period this area formed the part of the Mauryan Empire and according to Asokavadana the Emperor Asoka put to death many naked heretics of this area who had done despite to the Budhist religion. In the 6th century A.D. the area south of the Himalayan pilgrim center of Varaha Kshetra, namely the Gupta kings Budhgupta and Devagupta gave Koti-varsha for the maintenance of the said pilgrim centre. In the first war of independence of 1857 Araria also witnessed a few skirmishes between the mutineers and the commissioner Yule’s forces, which took place near Nathpur. -

Sr. No. District DLC Name Email ID Mobile No 1 Araria Amir Iqbal

Sr. No. District DLC Name Email ID Mobile No 1 Araria Amir Iqbal [email protected] 8521976983 2 Arwal DLC not present [email protected] 3 Aurangabad Nishant Saurbh [email protected] 9788879300 4 Banka Md Kaiser Alam [email protected] 8294112638 5 Begusarai Rituraj [email protected] 8825344040 6 Bhabhua Shahanwaz Manjar [email protected] 9555320020 7 Bhagalpur Sanjay Dohale [email protected] 9970841919 8 Bhojpur Amol Gade [email protected] 9921535545 9 Buxar Deepu Kumar [email protected] 8271416859 10 Darbhanga Shubham Mishra [email protected] 8936891744 11 East Champaran Kunal Kumar [email protected] 7255009000 12 Gaya Akash Bankar [email protected] 9113455684 13 Gopalganj Farukh Shaha [email protected] 9657547701 14 Jamui DLC not present [email protected] 9689531871 15 Katihar Md Altaf [email protected] 7258071773 16 Khagaria DLC not present [email protected] 9689531871 17 Kishanganj Amir Iqbal [email protected] 8521976983 18 Lakhisarai Umesh Morje [email protected] 6200813116 19 Madhepura Nitesh Futak [email protected] 7507564841 20 Madhubani Vidhyadhar Waghmare [email protected] 8084669093 21 Muzaffarpur Krishna Kumar [email protected] 9546036544 22 Nalanda Ranjeet Kumar [email protected] 7003201099 23 Patna Ibhran Khatik [email protected] 8956309513 24 Patna Nitin Pradhan [email protected] 7020651780 25 Patna Ganesh Ghuge [email protected] 9471000794 26 Purnia Raja Kumar [email protected] 9097489959 27 Rohtas Raviranjan Thakur [email protected] 8210305044 28 Samastipur -

Bihar Building New Avenues of Progress Bihar

BIHAR BUILDING NEW AVENUES OF PROGRESS BIHAR Uttar Pradesh Jharkhand West Bengal In the State of Bihar, a popular destination for spiritual tourists from all over the world, the length of National Highways has been doubled in the past four years. Till 2014, the length of National Highways was 4,447 km. In 2018, the length of National Highways has reached 8,898 km. The number of National Highways have been increased to 102 in 2018. Road development works worth Rs. 20,000 Cr are progressing rapidly. In the next few years, investments worth Rs. 60,000 Cr will be made towards transforming the road sector in Bihar, and creating new socio-economic opportunities for the people. “When a network of good roads is created, the economy of the country also picks up pace. Roads are veins and arteries of the nation, which help to transform the pace of development and ensure that prosperity reaches the farthest corners of our nation.” NARENDRA MODI Prime Minister “In the past four years, we have expanded the length of Indian National Highways network to 1,26,350 km. The highway sector in the country has seen a 20% growth between 2014 and 2018. Tourist destinations have come closer. Border, tribal and backward areas are being connected seamlessly. Multimodal integration through road, rail and port connectivity is creating socio economic growth and new opportunities for the people. In the coming years, we have planned projects with investments worth over Rs 6 lakh crore, to further expand the world’s second largest road network.” NITIN GADKARI Union Minister, -

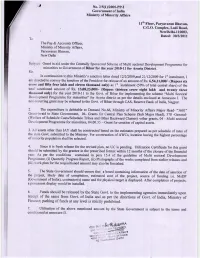

Grant-In-Aid Under the Centrally Sponsored Scheme of Multi

No. 3/5(1)12008-PP-I Government of India Ministry of Minority Affairs 11 th Floor, Paryavaran Bhavan, C.G.O. Complex, Lodi Road, NewDelhi-110003, Dated: 30/3/2011 To The Pay & Accounts Officer, Ministry of Minority Affairs, Paryavaran Bhavan, New Delhi Subject: Grant in aid under the Centrally Sponsored Scheme of Multi sectoral Development Programme for minorities to Government of Bihar for the year 2010-11 for Araria District. Sir, In continuation to this Ministry's sanction letter dated 12/2/2009,and 21/12/2009 for 1' instalment, I am directed to convey the sanction of the President for release of an amount of Rs. 6,54,11,000/- (Rupees six crore and fifty four lakh and eleven thousand only) as 1' instalment (50% of total central share) of the total sanctioned amount of Rs. 13,08,23,000/- (Rupees thirteen crore eight lakh and twenty three thousand only) for the year 2010-11 to the Govt. of Bihar for implementing the scheme "Multi Sectoral Development Programme for minorities" for Araria district as per the details enclosed at Annexure I. The non-recurring grant may be released to the Govt. of Bihar through CAS, Reserve Bank of India, Nagpur. 2. The expenditure is debitable to Demand No.66, Ministry of Minority Affairs Major Head- "3601" Grant-in-aid to State Government, 04- Grants for Central Plan Scheme (Sub Major Head), 378 -General- (Welfare of Schedule Casts/Schedule Tribes and Other Backward Classes) -other grants, 04 - Multi sectoral Development Programme for minorities, 04.00.35 — Grant for creation of capital assets.