Tony Kushner's <I>Angels in America</I>

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 200 Plays That Every Theatre Major Should Read

The 200 Plays That Every Theatre Major Should Read Aeschylus The Persians (472 BC) McCullers A Member of the Wedding The Orestia (458 BC) (1946) Prometheus Bound (456 BC) Miller Death of a Salesman (1949) Sophocles Antigone (442 BC) The Crucible (1953) Oedipus Rex (426 BC) A View From the Bridge (1955) Oedipus at Colonus (406 BC) The Price (1968) Euripdes Medea (431 BC) Ionesco The Bald Soprano (1950) Electra (417 BC) Rhinoceros (1960) The Trojan Women (415 BC) Inge Picnic (1953) The Bacchae (408 BC) Bus Stop (1955) Aristophanes The Birds (414 BC) Beckett Waiting for Godot (1953) Lysistrata (412 BC) Endgame (1957) The Frogs (405 BC) Osborne Look Back in Anger (1956) Plautus The Twin Menaechmi (195 BC) Frings Look Homeward Angel (1957) Terence The Brothers (160 BC) Pinter The Birthday Party (1958) Anonymous The Wakefield Creation The Homecoming (1965) (1350-1450) Hansberry A Raisin in the Sun (1959) Anonymous The Second Shepherd’s Play Weiss Marat/Sade (1959) (1350- 1450) Albee Zoo Story (1960 ) Anonymous Everyman (1500) Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf Machiavelli The Mandrake (1520) (1962) Udall Ralph Roister Doister Three Tall Women (1994) (1550-1553) Bolt A Man for All Seasons (1960) Stevenson Gammer Gurton’s Needle Orton What the Butler Saw (1969) (1552-1563) Marcus The Killing of Sister George Kyd The Spanish Tragedy (1586) (1965) Shakespeare Entire Collection of Plays Simon The Odd Couple (1965) Marlowe Dr. Faustus (1588) Brighton Beach Memoirs (1984 Jonson Volpone (1606) Biloxi Blues (1985) The Alchemist (1610) Broadway Bound (1986) -

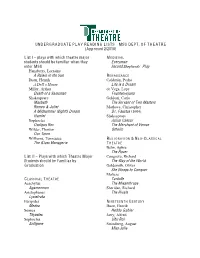

Undergraduate Play Reading List

UND E R G R A DU A T E PL A Y R E A DIN G L ISTS ± MSU D EPT. O F T H E A T R E (Approved 2/2010) List I ± plays with which theatre major M E DI E V A L students should be familiar when they Everyman enter MSU Second 6KHSKHUGV¶ Play Hansberry, Lorraine A Raisin in the Sun R E N A ISSA N C E Ibsen, Henrik Calderón, Pedro $'ROO¶V+RXVH Life is a Dream Miller, Arthur de Vega, Lope Death of a Salesman Fuenteovejuna Shakespeare Goldoni, Carlo Macbeth The Servant of Two Masters Romeo & Juliet Marlowe, Christopher A Midsummer Night's Dream Dr. Faustus (1604) Hamlet Shakespeare Sophocles Julius Caesar Oedipus Rex The Merchant of Venice Wilder, Thorton Othello Our Town Williams, Tennessee R EST O R A T I O N & N E O-C L ASSI C A L The Glass Menagerie T H E A T R E Behn, Aphra The Rover List II ± Plays with which Theatre Major Congreve, Richard Students should be Familiar by The Way of the World G raduation Goldsmith, Oliver She Stoops to Conquer Moliere C L ASSI C A L T H E A T R E Tartuffe Aeschylus The Misanthrope Agamemnon Sheridan, Richard Aristophanes The Rivals Lysistrata Euripides NIN E T E E N T H C E N T UR Y Medea Ibsen, Henrik Seneca Hedda Gabler Thyestes Jarry, Alfred Sophocles Ubu Roi Antigone Strindberg, August Miss Julie NIN E T E E N T H C E N T UR Y (C O N T.) Sartre, Jean Shaw, George Bernard No Exit Pygmalion Major Barbara 20T H C E N T UR Y ± M ID C E N T UR Y 0UV:DUUHQ¶V3rofession Albee, Edward Stone, John Augustus The Zoo Story Metamora :KR¶V$IUDLGRI9LUJLQLD:RROI" Beckett, Samuel E A R L Y 20T H C E N T UR Y Waiting for Godot Glaspell, Susan Endgame The Verge Genet Jean The Verge Treadwell, Sophie The Maids Machinal Ionesco, Eugene Chekhov, Anton The Bald Soprano The Cherry Orchard Miller, Arthur Coward, Noel The Crucible Blithe Spirit All My Sons Feydeau, Georges Williams, Tennessee A Flea in her Ear A Streetcar Named Desire Synge, J.M. -

Unmatched: Buffy the Vampire Slayer Rulebook

RULES THE UNMATCHED SYSTEM Unmatched is a miniatures dueling game featuring fighters of all kinds — from the page to the screen to the stuff of legends. Each hero has a unique deck of cards that fits their fighting style. You can mix and match fighters from 03 any Unmatched set. But remember, in the end, there can only be one winner. All of your characters in the battle are HEROES& called your fighters, but your primary CONTENTS fighter is called your hero. Heroes are represented by miniatures that move SIDEKICKS around on the battlefield. 3 BUFFY Your other fighters are called sidekicks. All of the heroes RAPID RECOVERY in this set have a single sidekick. (Some heroes in other sets 3 AFTER COMBAT: ACTION CARDS ACTION 1 health. Buffy recovers have multiple sidekicks, and still other heroes have no sidekick HERO MINIATURES HEALTH DIALS HEALTH BUFFY 25 | x3 4 1 8 at all.) Sidekicks are represented by tokens that move around on the battlefield. HERO BUFFY MELEE ATTACK Each hero has a special ability noted on their character card. START 14 HEALTH Buffy may move through spaces containing opposing This card also lists your fighters’ stats, including the starting fighters (including when 3 she is moved by effects). health of your hero and their sidekick. Fighters’ health is SPECIAL ABILITY ™ & © 20th Century Fox BATTLEFIELDS MOVE 2 SIDEKICK GILES OR XANDER tracked on separate health dials. Fighters cannot gain health CHARACTER CARDS CHARACTER MELEE SIDEKICK TOKENS ATTACK START 6 HEALTH DOUBLE-SIDED BOARD DOUBLE-SIDED 4 4 1 WITH higher than the highest number on their health dial. -

Twelfth Night Study Guide — 2 Twelfth Night a Support Packet for Studying the Play and Attending the Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey’S Main Stage Production

a study guide compiled and arranged by the Education Department of The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey Twelfth Night study guide — 2 Twelfth Night a support packet for studying the play and attending The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey’s Main Stage production General Information p3- Using This Study Guide p16- Sources for this Study Guide (and Additional Resources) William Shakespeare p4- Shakespeare: Helpful Tips for Exploring & Seeing His Works p5- The Life of William Shakespeare p5- Shakespeare’s London p6- Are You SURE This Is English? About The Play p7- Twelfth Night: A Synopsis p8- Sources and History of the Play p10- Commentary and Criticism Studying Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night p9- Shakespeare’s Common Tongue p9- Terms and Phrases found in Twelfth Night p11- Aspects of Twelfth Night p12- Twelfth Night: Food For Thought p13- Additional Topics for Discussion Classroom Applications p13- Follow-Up Activities p14- What Did He Say? p14- Who Said That? p15- Meeting the Core Curriculum Content Standards p16- “Who Said That?” Answer Key About the Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey p17- About The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey p17- Other Opportunities for Students... and Teachers The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey is an independent, professional theatre located on the Drew University campus. The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey’s programs are made possible, in part, by funding from the New Jersey State Council on the Arts/ Department of State, a Partner Agency of the National Endowment for the Arts, as well as funds from the National Endowment for the Arts. -

PHILLIP OWEN Sound Design Resume 8-24-21

Phillip Owen, Sound Designer www.phillipowen.com Plays Company Director Year Broadway A Steady Rain (assisted composer) Schoenfeld Theatre Mark Bennett (composer) 2009 Regional Camp David Alley Theatre Oskar Eustice 2020 Dancing at Lughnasa* Everyman Theatre Amber Page McGuinness 2018 Building the Wall University of Texas/TPA Brant Pope 2017 Noises Off Everyman Theatre Vincent Lancisi 2017 I and You Stages Rep Seth Gordon 2016 Syncing Ink Alley Theatre Niegel Smith 2015 Miller, Mississippi Alley Theatre Lee Sunday Evans 2015 Roz & Ray Alley Theatre Chay Yew 2015 A Streetcar Named Desire Texas State Univ. Michael Costello 2015 Outside Mullingar Everyman Theatre Donald Hicken 2014 Stupid F#$%ing Bird Stages Rep Kenn McLaughlin 2014 A Midsummer Night’s Dream Texas State Univ. Chuck Ney 2014 Common Enemy Triad Stage Preston Lane 2013 The Whipping Man Stages Rep Seth Gordon 2013 Cymbeline Stonington Opera House Julia Whitworth 2013 Anna Christie Triad Stage Preston Lane 2013 Dollhouse Stages Rep Eva La Porte 2013 Kingdom of Earth Triad Stage Preston Lane 2012 A Wrinkle in Time Main Street Theatre Troy Scheid 2012 Antony & Cleopatra Stonington Opera House Craig Baldwin 2012 Steel Magnolias Stages Rep Kenn MacLaughlin 2011 A Lie of the Mind St. Edward’s University Jared Stein 2011 Measure for Measure Stonington Opera House Jeffery Frace 2011 Notes From Underground Yale Rep, La Jolla, Barishnikov Arts Center Robert Woodruff 2010 Rough Crossing Yale Repertory Mark Rucker 2009 Waking Yale Cabaret Phillip Owen 2009 In The Cypher Yale Cabaret Patricia Macgregor 2008 Ghost Sonata Yale School of Drama Shana Cooper 2007 Vaudeville Vanya St. -

A Comparative Evaluation of Group and Private Piano Instruction on the Musical Achievements of Young Beginners

A Comparative Evaluation of Group and Private Piano Instruction on the Musical Achievements of Young Beginners Pai-Yu Chiu A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctoral of Music and Arts University of Washington 2017 Reading Committee: Craig Sheppard, Chair Donna Shin Steven J. Morrison Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Music © Copyright 2017 Pai-Yu Chiu ii University of Washington Abstract A Comparative Evaluation of Group and Private Piano Instruction on the Musical Achievements of Young Beginners Pai-Yu Chiu Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Craig Sheppard School of Music This study compares the relative influence of group and individual piano instruction on the musical achievements of young beginning piano students between the ages of 5 to 7. It also investigates the potential influence on these achievements of an individual teacher’s preference for either mode of instruction, children’s age and gender, and identifies relationships between these three factors and the two different modes of instruction. Forty-five children between the ages of 5 to 7 without previous musical training completed this empirical study, which consisted of 24 weekly piano instruction and a posttest evaluating their musical achievements. The 45 participants included 25 boys and 20 girls. The participants were comprised of twenty-seven 5- year-olds, nine 6-year-olds, and nine 7-year-old participants. Twenty-two children participated in group piano instruction and 23 received private instruction. After finishing 24 weekly lessons, participants underwent a posttest evaluating: (1) music knowledge, (2) music reading, (3) aural iii discrimination, (4) kinesthetic response, and (5) performance skill. -

“My” Hero Or Epic Fail? Torchwood As Transnational Telefantasy

“My” Hero or Epic Fail? Torchwood as Transnational Telefantasy Melissa Beattie1 Recibido: 2016-09-19 Aprobado por pares: 2017-02-17 Enviado a pares: 2016-09-19 Aceptado: 2017-03-23 DOI: 10.5294/pacla.2017.20.3.7 Para citar este artículo / to reference this article / para citar este artigo Beattie, M. (2017). “My” hero or epic fail? Torchwood as transnational telefantasy. Palabra Clave, 20(3), 722-762. DOI: 10.5294/pacla.2017.20.3.7 Abstract Telefantasy series Torchwood (2006–2011, multiple production partners) was industrially and paratextually positioned as being Welsh, despite its frequent status as an international co-production. When, for series 4 (sub- titled Miracle Day, much as the miniseries produced as series 3 was subti- tled Children of Earth), the production (and diegesis) moved primarily to the United States as a co-production between BBC Worldwide and Amer- ican premium cable broadcaster Starz, fan response was negative from the announcement, with the series being termed Americanised in popular and academic discourse. This study, drawn from my doctoral research, which interrogates all of these assumptions via textual, industrial/contextual and audience analysis focusing upon ideological, aesthetic and interpretations of national identity representation, focuses upon the interactions between fan cultural capital and national cultural capital and how those interactions impact others of the myriad of reasons why the (re)glocalisation failed. It finds that, in part due to the competing public service and commercial ide- ologies of the BBC, Torchwood was a glocalised text from the beginning, de- spite its positioning as Welsh, which then became glocalised again in series 4. -

City Officials from Across the State Named “Home Rule Heroes”

301 S. Bronough Street, Suite 300 ● Post Office Box 1757 ● Tallahassee, FL 32302-1757 (850) 222-9684 ● Fax: (850) 222-3806 ● Website: flcities.com City Officials from Across the State Named “Home Rule Heroes” The Florida League of Cities recognizes local officials for their advocacy efforts during legislative session FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: May 9, 2019 CONTACT: Brittni Johnsen [email protected] / (850) 701-3652 The Florida League of Cities is recognizing more than 100 municipal officials with Home Rule Hero Awards for their work during the 2019 legislative session. These local leaders earned this award for their tireless efforts to protect the Home Rule powers of Florida’s municipalities and advance the League’s legislative agenda. “The dedication and effort of these local officials during the 2019 legislative session was extraordinary,” said FLC Legislative Director Scott Dudley. “These are some of our biggest advocates for municipal issues, and they’re shining examples of local advocacy in action. On behalf of the League and its legislative team, we’re proud to recognize each and every one of them and thank them for their service.” Home Rule is the ability for a city to address local problems with local solutions with minimal state interference. Home Rule Hero Award recipients are local government officials, both elected and nonelected, who consistently responded to the League’s request to reach out to members of the legislature and help give a local perspective to an issue. The 2019 Home Rule Hero Award recipients are: City Title Name City of Altamonte Springs Mayor Pat Bates City of Arcadia Councilmember Judy Wertz-Strickland City of Atlantic Beach Mayor Ellen Glasser City of Bartow Commissioner Leo E. -

F. Scott Fitzgerald the Stand

Fiction Songs The Great Gatsby – F. Scott Fitzgerald “Change is Gonna Come” – Sam Cooke The Stand - Stephen King “Oh Holy Night” – Adolph Adam Things Fall Apart – Chinua Achebe “Come as You Are” – Nirvana Brave New World – Aldous Huxley “Paper Tiger” – Beck The Alchemist – Paulo Coelho “Sweet Child O’ Mine” – Guns N Roses Nineteen Eighty Four – George Orwell “Amazing Grace” – John Newton Of Mice and Men – John Steinbeck “Father and Son” – Cat Stevens The Road – Cormac McCarthy “Go or Go Ahead” – Rufus Wainright The Lovely Bones – Alice Sebold “And Justice For All” – Metallica The Fountainhead – Ayn Rand “In My Life” – The Beetles Non-fiction Movies A Brief History of Time – Stephen Hawking The Godfather – Francis Ford Coppola My Life in Art – Konstantin Stanislavsky Magnolia – Paul Thomas Anderson The Singularity is Near – Ray Kurzweil It’s a Wonderful Life – Frank Capra The Tipping Point – Malcolm Gladwell Being John Malkovich – Spike Jonze Bossypants – Tina Fey Life is Beautiful – Roberto Benigni Revelation – John (The One Who Jesus Loved) Gone With the Wind – Victor Fleming The Supernatural Worldview – Cris Putnam Lost in Translation – Sophia Coppola Relativity – Albert Einstein Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind – In Cold Blood – Truman Capote Michel Gondry Exodus – Moses The Sting – George Roy Hill The Little Princess – Walter Lang Children’s Books Documentaries The Giving Tree – Shel Silverstein Grey Gardens – Ellen Hoyde, Albert Maysles The Chronicles of Narnia series– C.S. Lewis The Imposter – Bart Layton Every Amelia Bedelia – Peggy/Herman Parish Hoop Dreams – Steve James Charlotte’s Web – E.B. White Fahrenheit 911 – Michael Moore The Cat in the Hat – Dr. -

Uniting Commedia Dell'arte Traditions with the Spieltenor Repertoire

UNITING COMMEDIA DELL’ARTE TRADITIONS WITH THE SPIELTENOR REPERTOIRE Corey Trahan, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2012 APPROVED: Stephen Austin, Major Professor Paula Homer, Committee Member Lynn Eustis, Committee Member and Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James Scott, Dean of the School of Music James R. Meernik, Acting Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Trahan, Corey, Uniting Commedia dell’Arte Traditions with the Spieltenor repertoire. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2012, 85 pp., 6 tables, 35 illustrations, references, 84 titles. Sixteenth century commedia dell’arte actors relied on gaudy costumes, physical humor and improvisation to entertain audiences. The spieltenor in the modern operatic repertoire has a similar comedic role. Would today’s spieltenor benefit from consulting the commedia dell’arte’s traditions? To answer this question, I examine the commedia dell’arte’s history, stock characters and performance traditions of early troupes. The spieltenor is discussed in terms of vocal pedagogy and the fach system. I reference critical studies of the commedia dell’arte, sources on improvisatory acting, articles on theatrical masks and costuming, the commedia dell’arte as depicted by visual artists, commedia dell’arte techniques of movement, stances and postures. In addition, I cite vocal pedagogy articles, operatic repertoire and sources on the fach system. My findings suggest that a valid relationship exists between the commedia dell’arte stock characters and the spieltenor roles in the operatic repertoire. I present five case studies, pairing five stock characters with five spieltenor roles. -

'Bite Me': Buffy and the Penetration of the Gendered Warrior-Hero

Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies, Vol. 16, No. 2, 2002 ‘Bite Me’: Buffy and the penetration of the gendered warrior-hero SARA BUTTSWORTH, University of Western Australia Introduction Can the ultimate girl be the ultimate warrior? If warrior identity is simultaneously a quintessentially masculine identi er, and one of the core expressions of ‘innate’ masculinity, then the biggest transgression of warrior iconography posed by Buffy the Vampire Slayer is Buffy’s gender. Buffy is both like and not like ‘other girls’. The social conventions of mainstream femininity, which have so often been used to argue that women cannot be warriors, are often precisely what make Buffy such an effective soldier in her speculative world. The blurred boundaries that are possible in speculative texts open up space necessary to examine the arguments and gendered ideologies which govern what is, and what is not, possible in the ‘real’ world. Such texts can often make explicit what is implied in more ‘realistic’ representations, and can either destabilize or reinforce gendered cultural conventions.1 Established as the ‘chosen one’ in the 1992 lm, and then in the television series which debuted mid-season in 1997, Buffy has slashed her way not only through the ctional constraints placed upon her predecessors in vampire carnage, but through the conventions governing gendered constructions of the warrior.2 Warrior tradition con- structs a coherent masculinity, including impenetrable male bodies, as the key to warrior identity, and renders ‘slay-gal’3 not only paradoxical but, arguably, impossible. It is this (im)possibility, and the ways in which Buffy the Vampire Slayer fractures and reinvents the gendered identity of the warrior-hero, which are explored in this article. -

English 3490G (001) American Drama: Home Sweet Home Winter 2018

Department of English & Writing Studies English 3490G (001) American Drama: Home Sweet Home Winter 2018 Dr. Alyssa MacLean Class Location: P&AB 150 Email: [email protected] Class Time: Tuesdays 11:30 am -12:30 pm, Tel: (519) 661-2111 ext. 87416 Thursdays 11:30 am-1:30 pm Office: Arts and Humanities 1G33 Office Hours: Wed 11-12:30, Thurs 1:30-3:00, and by appointment Antirequisite(s): English 2460F/G. Prerequisite(s): At least 60% in 1.0 of English 1020E or 1022E or 1024E or 1035E or 1036E or both of English 1027F/G and 1028F/G, or permission of the Department. Unless you have either the requisites for this course or written special permission from your Dean to enroll in it, you may be removed from this course and it will be deleted from your record. This decision may not be appealed. You will receive no adjustment to your fees in the event that you are dropped from a course for failing to have the necessary prerequisites. Course Description: This course will focus on the idea of home in the United States. The living room is perhaps the most ubiquitous of settings in American drama, but it is a complex space, a battleground upon which larger conflicts in American culture are staged. Derived from the eighteenth-century parlor (a room that was named after the French word parler), the living room’s purpose in the twentieth century was to receive guests and support the moral growth of the family by encouraging discussion and self-improvement.