Home and Family

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs About Joni

Songs About Joni Compiled by: Simon Montgomery, © 2003 Latest Update: Dec. 28, 2020 Please send comments, corrections or additions to: [email protected] © Ed Thrasher, March 1968 Song Title Musician Album / CD Title 1967 Lady Of Rohan Chuck Mitchell Unreleased 1969 Song To A Cactus Tree Graham Nash Unreleased Why, Baby Why Graham Nash Unreleased Guinnevere Crosby, Stills & Nash Crosby, Stills & Nash Pre-Road Downs Crosby, Stills & Nash Crosby, Stills & Nash Portrait Of The Lady As A Young Artist Seatrain Seatrain (Debut LP) 1970 Only Love Can Break Your Heart Neil Young After The Goldrush Our House Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young Déjà Vu 1971 Just Joni Mitchell Charles John Quarto Unreleased Better Days Graham Nash Songs For Beginners I Used To Be A King Graham Nash Songs For Beginners Simple Man Graham Nash Songs For Beginners Love Has Brought Me Around James Taylor Mudslide Slim & The Blue Horizon You Can Close Your Eyes James Taylor Mudslide Slim & The Blue Horizon 1972 New Tune James Taylor One Man Dog 1973 It's Been A Long Time Eric Andersen Stages: The Lost Album You'’ll Never Be The Same Graham Nash Wild Tales Song For Joni Dave Van Ronk songs for ageing children Sweet Joni Neil Young Unreleased Concert Recording 1975 She Lays It On The Line Ronee Blakley Welcome Mama Lion David Crosby / Graham Nash Wind On The Water 1976 I Used To Be A King David Crosby / Graham Nash Crosby-Nash LIVE Simple Man David Crosby / Graham Nash Crosby-Nash LIVE Mama Lion David Crosby / Graham Nash Crosby-Nash LIVE Song For Joni Denise Kaufmann Dream Flight Mellow -

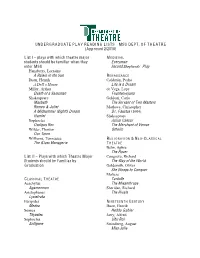

Undergraduate Play Reading List

UND E R G R A DU A T E PL A Y R E A DIN G L ISTS ± MSU D EPT. O F T H E A T R E (Approved 2/2010) List I ± plays with which theatre major M E DI E V A L students should be familiar when they Everyman enter MSU Second 6KHSKHUGV¶ Play Hansberry, Lorraine A Raisin in the Sun R E N A ISSA N C E Ibsen, Henrik Calderón, Pedro $'ROO¶V+RXVH Life is a Dream Miller, Arthur de Vega, Lope Death of a Salesman Fuenteovejuna Shakespeare Goldoni, Carlo Macbeth The Servant of Two Masters Romeo & Juliet Marlowe, Christopher A Midsummer Night's Dream Dr. Faustus (1604) Hamlet Shakespeare Sophocles Julius Caesar Oedipus Rex The Merchant of Venice Wilder, Thorton Othello Our Town Williams, Tennessee R EST O R A T I O N & N E O-C L ASSI C A L The Glass Menagerie T H E A T R E Behn, Aphra The Rover List II ± Plays with which Theatre Major Congreve, Richard Students should be Familiar by The Way of the World G raduation Goldsmith, Oliver She Stoops to Conquer Moliere C L ASSI C A L T H E A T R E Tartuffe Aeschylus The Misanthrope Agamemnon Sheridan, Richard Aristophanes The Rivals Lysistrata Euripides NIN E T E E N T H C E N T UR Y Medea Ibsen, Henrik Seneca Hedda Gabler Thyestes Jarry, Alfred Sophocles Ubu Roi Antigone Strindberg, August Miss Julie NIN E T E E N T H C E N T UR Y (C O N T.) Sartre, Jean Shaw, George Bernard No Exit Pygmalion Major Barbara 20T H C E N T UR Y ± M ID C E N T UR Y 0UV:DUUHQ¶V3rofession Albee, Edward Stone, John Augustus The Zoo Story Metamora :KR¶V$IUDLGRI9LUJLQLD:RROI" Beckett, Samuel E A R L Y 20T H C E N T UR Y Waiting for Godot Glaspell, Susan Endgame The Verge Genet Jean The Verge Treadwell, Sophie The Maids Machinal Ionesco, Eugene Chekhov, Anton The Bald Soprano The Cherry Orchard Miller, Arthur Coward, Noel The Crucible Blithe Spirit All My Sons Feydeau, Georges Williams, Tennessee A Flea in her Ear A Streetcar Named Desire Synge, J.M. -

Clybourne Park Study Guide

Clybourne Park Study Guide The Theatre/Dance Department’s production oF Clybourne Park can be seen December 2 – 7 at 7:30 pm in Barnett Theatre. Tickets 262-472-2222 Monday – Friday 9:30 am – 5:00 pm The Clybourne Park Study Guide was originally created by Studio 180 Theatre, Toronto, Canada, and is being used at UW-Whitewater with Studio 180 Theatre’s permission. www.studio180theatre.com Table of Contents A. Notes for Teachers ...................................................................................................................... 3 B. Introduction to the Company and the Play .................................................................................. 4 UW-Whitewater Theatre/Dance Department .......................................................................................................... 4 Clybourne Park by Bruce Norris ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Bruce Norris – Playwright ................................................................................................................................................. 6 C. Attending the Performance ......................................................................................................... 7 D. Background Information ............................................................................................................. 8 1. Source Material: A Raisin in the Sun by Lorraine Hansberry ....................................................................... -

Heart-Shaped Box Pdf, Epub, Ebook

HEART-SHAPED BOX PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Joe Hill | 416 pages | 01 May 2008 | Orion Publishing Co | 9780575081864 | English | London, United Kingdom Heart-shaped Box PDF Book It seemed like Hill just wanted to quickly wrap it up, no matter how many questions it either raised or left unanswered. A good old fashioned ghost story. View all 13 comments. He told biographer Michael Azerrad , "Anytime I think about it, it makes me sadder than anything I can think of. US Alternative Songs Billboard [2] [3]. October 16, Just hate our MC and pray that Georgia makes it out with the rest of us. Official Charts Company. The characters are unlika I had pretty big expectations for this novel, since it was somewhat of a happening in the horror genre and was praised by writers such as Harlan Coben and Neil Gaiman. The ghost in this story is Liam Neeson of Ghosts. I'm going to keep this spoiler free, but if you enjoyed NOS4A2, you will probably like this one as well. Thanks for telling us about the problem. New York City: Time, Inc. Unf Imagine a ghost! Aging rock star Judas Coyne spends his retirement collecting morbid memorabilia, including a witch's confession, a real snuff film and, after being sent an email directly about the item online, a dead man's funeral suit. Joe Hill surprised me with his clever plot and seemingly unlovable characters, I was turning the pages like there was no tomorrow for the last pages and didn't guess the ending. We sing together. Read more This book sucks. -

Multiculturalism and Transnational Formations in Tony Kushner's

Multiculturalism and Transnational Formations in Tony Kushner’s Angels in America Yvonne Iden Ngwa Higher Teacher Training School. (ENS) Yaoundé [email protected] Resum Multiculturalisme i formacions transnacionals a Angels in America de Tony Kushner En aquest article es vol demostrar que la representació del multiculturalisme ambient a Amèrica vist per Tony Kushner és palesa a la seva obra Angels in America a través de formacions transnacionals. La seva especificitat rau en el fet de recórrer els diferents aspectes del multiculturalisme. Les teories postcolonials i postmodernes posen de relleu l’heterogeneïtat que caracteritza les cultures a l’obra i justifiquen el multiculturalisme i el transnacionalisme. Paraules clau Multiculturalisme, formacions transnacionals, Tony Kushner. Resumen Multiculturalismo y formaciones transnacionales en Angels in America de Tony Kushner En este artículo, se quiere demostrar que la representación del multiculturalismo ambiente en América por Tony Kushner desemboca en formaciones transnacionales en su obra Angels in America. Lo que hace su especificidad es que recorre los distintos aspectos del multiculturalismo. Las teorías postcoloniales y postmodernas ponen de relieve la heterogeneidad que caracteriza las culturas en la obra y justifican el multiculturalismo y el transnacionalismo. Palabras clave Multiculturalismo, formaciones transnacionales, Tony Kushner. Résumé Multiculturalisme et formations transnationales dans Angels in America de Tony Kushner Dans cet article, on veut montrer que la représentation du multiculturalisme ambiant de l’Amérique par Tony Kushner aboutit à des formations transnationales dans sa pièce Angels in America. Contrairement aux autres articles qui décrivent généralement le multiculturalisme dont regorge la pièce, celui-ci s’intéresse aux différents contours de ce multiculturalisme ainsi qu’aux formations transnationales qui en découlent. -

A Comparative Evaluation of Group and Private Piano Instruction on the Musical Achievements of Young Beginners

A Comparative Evaluation of Group and Private Piano Instruction on the Musical Achievements of Young Beginners Pai-Yu Chiu A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctoral of Music and Arts University of Washington 2017 Reading Committee: Craig Sheppard, Chair Donna Shin Steven J. Morrison Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Music © Copyright 2017 Pai-Yu Chiu ii University of Washington Abstract A Comparative Evaluation of Group and Private Piano Instruction on the Musical Achievements of Young Beginners Pai-Yu Chiu Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Craig Sheppard School of Music This study compares the relative influence of group and individual piano instruction on the musical achievements of young beginning piano students between the ages of 5 to 7. It also investigates the potential influence on these achievements of an individual teacher’s preference for either mode of instruction, children’s age and gender, and identifies relationships between these three factors and the two different modes of instruction. Forty-five children between the ages of 5 to 7 without previous musical training completed this empirical study, which consisted of 24 weekly piano instruction and a posttest evaluating their musical achievements. The 45 participants included 25 boys and 20 girls. The participants were comprised of twenty-seven 5- year-olds, nine 6-year-olds, and nine 7-year-old participants. Twenty-two children participated in group piano instruction and 23 received private instruction. After finishing 24 weekly lessons, participants underwent a posttest evaluating: (1) music knowledge, (2) music reading, (3) aural iii discrimination, (4) kinesthetic response, and (5) performance skill. -

Staging the Scientist: the Representation of Science and Its Processes in American and British Drama

Staging the Scientist: The Representation of Science and its Processes in American and British Drama Aneta Marta Malinowska Dissertação de Mestrado em Estudos Ingleses e Norte Americanos Abril de 2014 Dissertação apresentada para cumprimento dos requisitos necessários à obtenção do grau de Mestre em Estudos Ingleses e Norte Americanos, realizada sob a orientação científica de Professora Teresa Botelho “Putting on a play is a sort of a scientific experiment. You go into a rehearsal room which is sort of an atom and a lot of these rather busy particles, the actors, do their work and circle around the nucleus of a good text. And then, when you think you’re ready to be seen you sell tickets to a lot of photons, that is an audience, who will shine a light of their attention on what you’ve been up to.” Michael Blakemore, Director of Copenhagen ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For my endeavor, I am actually indebted to a number of people without whom this study would not have been possible. First of all, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my parents for their love, support and understanding that they have demonstrated in the last two years. I dedicate this dissertation to them. I am also grateful to Professor Teresa Botelho for her guidance and supervision during the course as well as for providing me with the necessary information regarding the research project. My special thanks also goes to Marta Bajczuk and Valter Colaço who have willingly helped me out with their abilities and who have given me a lot of attention and time when it was most required. -

The Heidi Chronicles As Illustration of the Second Feminist Wave in the United States

Facultad de Humanidades Sección de Filología The Heidi Chronicles as Illustration of the Second Feminist Wave in the United States Trabajo de Fin de Grado presentado por la alumna Beatriz Sánchez Ramos bajo la supervisión de la Dra. Matilde Martín González Dpto. Filología Inglesa y Alemana Grado en Estudios Ingleses Curso 2014-15 Convocatoria de julio de 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract 1. Introduction 2. Second Feminist Wave: A Brief Account 3. The Heidi Chronicles seen from the perspective of Second Wave Feminist Theory 4. Conclusion 5. Works Cited Abstract This final degree dissertation aims to show how vital was the Second Wave Feminism in the twentieth century in terms of women’s struggle for better conditions. This period of intense fight has been the object of many literary and critical works, such as novels, collections of poetry and scholarly articles. From the huge bibliography on this topic I have chosen to focus on The Heidi Chronicles, a play written by Wendy Wasserstein (1950-2006) which reflects and engages with the main concerns raised by women in the period covering the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. Thus, I argue that this text could very well illustrate the political, social and theoretical aspects developed within the Second Feminist Wave in the United States. A further reason for choosing this work has to do with the possibilities of theatre as a cultural manifestation to deal with questions that include gender relations and social themes. The theatre has always implied an interaction between characters in a literal way, and this turns it perhaps into the most straightforward genre to involve the public – the audience – or the readership. -

Why We Play: an Anthropological Study (Enlarged Edition)

ROBERTE HAMAYON WHY WE PLAY An Anthropological Study translated by damien simon foreword by michael puett ON KINGS DAVID GRAEBER & MARSHALL SAHLINS WHY WE PLAY Hau BOOKS Executive Editor Giovanni da Col Managing Editor Sean M. Dowdy Editorial Board Anne-Christine Taylor Carlos Fausto Danilyn Rutherford Ilana Gershon Jason Troop Joel Robbins Jonathan Parry Michael Lempert Stephan Palmié www.haubooks.com WHY WE PLAY AN ANTHROPOLOGICAL STUDY Roberte Hamayon Enlarged Edition Translated by Damien Simon Foreword by Michael Puett Hau Books Chicago English Translation © 2016 Hau Books and Roberte Hamayon Original French Edition, Jouer: Une Étude Anthropologique, © 2012 Éditions La Découverte Cover Image: Detail of M. C. Escher’s (1898–1972), “Te Encounter,” © May 1944, 13 7/16 x 18 5/16 in. (34.1 x 46.5 cm) sheet: 16 x 21 7/8 in. (40.6 x 55.6 cm), Lithograph. Cover and layout design: Sheehan Moore Typesetting: Prepress Plus (www.prepressplus.in) ISBN: 978-0-9861325-6-8 LCCN: 2016902726 Hau Books Chicago Distribution Center 11030 S. Langley Chicago, IL 60628 www.haubooks.com Hau Books is marketed and distributed by Te University of Chicago Press. www.press.uchicago.edu Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Table of Contents Acknowledgments xiii Foreword: “In praise of play” by Michael Puett xv Introduction: “Playing”: A bundle of paradoxes 1 Chronicle of evidence 2 Outline of my approach 6 PART I: FROM GAMES TO PLAY 1. Can play be an object of research? 13 Contemporary anthropology’s curious lack of interest 15 Upstream and downstream 18 Transversal notions 18 First axis: Sport as a regulated activity 18 Second axis: Ritual as an interactional structure 20 Toward cognitive studies 23 From child psychology as a cognitive structure 24 . -

Oral History Interview with H.R. Haldeman

California State Archives State Government Oral History Program Oral History Interview with H. R. HALDEMAN Regent, University of California, 1965-1967, 1968 June 18 and 25, 1991 Santa Barbara, California By Dale E. Treleven Oral History Program University of California, Los Angeles RESTRICTIONS ON THIS INTERVIEW None. LITERARY RIGHTS AND QUOTATION This manuscript is hereby made available for research purposes only. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the California State Archivist or the Head, Department of Special Collections, University Research Library, UCLA. Requests for permission to quote for publication should be addressed to: California State Archives 1020 0 Street, Room 130 Sacramento, CA 95814 or Department of Special Collections University Research Library 405 S. Hilgard Avenue UCLA Los Angeles, CA 90024-1575 The request should include identification of the specific passages and identification of the user. It is recommended that this oral history be cited as follows: H. R. Haldeman, Oral History Interview, Conducted 1991 by Dale E. Tre1even, UCLA Oral History Program, for the California State Archives State Government Oral History Program. Information California State Archives (916) 445-4293 March Fong Eu Research Room (916) 445-4293 1020 0 Street, Room 130 Exhibit Hall (916) 445-4293 Secretary of State Sacramento, CA 95814 Legislative Bill Service (916) 445-2832 (prior years) PREFACE On September 25, 1985, Governor George Deukmejian signed into law A.B. 2104 (Chapter 965 of the Statutes of 1985). This legislation established, under the administration of the California State Archives, a State Government Oral History Program "to provide through the use of oral history a continuing documentation of state policy development as reflected in California's legislative and executive history." The following interview is one of a series of oral histories undertaken for inclusion in the state program. -

As Tribute to the Daughters of the South: Illuminating the Work of Black Women Principals

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of Summer 2013 "A Song for You" As Tribute to the Daughters of the South: Illuminating the Work of Black Women Principals Beverly Cox Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd Part of the Curriculum and Social Inquiry Commons, Educational Leadership Commons, Elementary and Middle and Secondary Education Administration Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, and the Race and Ethnicity Commons Recommended Citation Cox, Beverly, ""A Song for You" As Tribute to the Daughters of the South: Illuminating the Work of Black Women Principals" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 859. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd/859 This dissertation (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “A SONG FOR YOU” AS TRIBUTE TO THE DAUGHTERS OF THE SOUTH: ILLUMINATING THE WORK OF BLACK WOMEN PRINCIPALS by BEVERLY COX (Under the Direction of Sabrina Ross) ABSTRACT Curriculum can be understood as a place of both struggle and possibility, where curriculum workers engage in complicated conversations about self, society, and the purposes of education (Pinar, 2004). Although curriculum theorists have contributed much to discussions of how to improve the current state of education, little attention in the field is given to the role that leadership can play in educational transformation (Ylimaki, 2011). -

4920 10 Cc D22-01 2Pac D43-01 50 Cent 4877 Abba 4574 Abba

ALDEBARAN KARAOKE Catálogo de Músicas - Por ordem de INTÉRPRETE Código INTÉRPRETE MÚSICA TRECHO DA MÚSICA 4920 10 CC I´M NOT IN LOVE I´m not in love so don´t forget it 19807 10000 MANIACS MORE THAN THIS I could feel at the time there was no way of D22-01 2PAC DEAR MAMA You are appreciated. When I was young 9033 3 DOORS DOWN HERE WITHOUT YOU A hundred days had made me older 2578 4 NON BLONDES SPACEMAN Starry night bring me down 9072 4 NON BLONDES WHAT´S UP Twenty-five years and my life is still D36-01 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER AMNESIA I drove by all the places we used to hang out D36-02 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER HEARTBREAK GIRL You called me up, it´s like a broken record D36-03 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER JET BLACK HEART Everybody´s got their demons even wide D36-04 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER SHE LOOKS SO PERFECT Simmer down, simmer down, they say we D43-01 50 CENT IN DA CLUB Go, go, go, go, shawty, it´s your birthday D54-01 A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS I RAN I walk along the avenue, I never thought I´d D35-40 A TASTE OF HONEY BOOGIE OOGIE OOGIE If you´re thinkin´ you´re too cool to boogie D22-02 A TASTE OF HONEY SUKIYAKI It´s all because of you, I´m feeling 4970 A TEENS SUPER TROUPER Super trouper beams are gonna blind me 4877 ABBA CHIQUITITA Chiquitita tell me what´s wrong 4574 ABBA DANCING QUEEN Yeah! You can dance you can jive 19333 ABBA FERNANDO Can you hear the drums Fernando D17-01 ABBA GIMME GIMME GIMME Half past twelve and I´m watching the late show D17-02 ABBA HAPPY NEW YEAR No more champagne and the fireworks 9116 ABBA I HAVE A DREAM I have a dream a song to sing…