Texto Completo.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Orchid of the Month for June, 2015 Oncidium Longipes by Bruce Adams

Orchid of the Month for June, 2015 Oncidium Longipes by Bruce Adams Figure 1: Oncidium longipes When I first fell in love with orchids, about forty years ago, Oncidium was my favorite genus. I loved the intricate flowers on long sprays, often with a wonderful fragrance. At that time, I worked as a volunteer in the orchid house at Planting Fields Arboretum. After repotting plants, I had the opportunity to take home back bulbs, and received pieces of Oncidium sphacelatum, O. flexuosum, and others that I can no longer remember. Every year they had an orchid auction, and for the extravagant price of five dollars, I purchased a multi-lead plant of O. ornithorhyncum. I became familiar with many of the various species, and at the time was a bit of an Oncidium expert. Forty years later, I’ve forgotten much, and with the recent changes in nomenclature maybe I wasn’t ever really an Oncidium expert, but rather a Trichocentrum, Gomesa, and Tolumnia expert! What hasn’t changed is my fondness for this vast genus (or group of genera). Plants can get quite large, such as Oncidium sphacelatum, which can easily can fill a twelve-inch pot, sending out three foot spikes with hundreds of flowers. But there are also miniatures like Oncidium harrisonianum, which can be contained in a three or four inch pot and sports short sprays of pretty little yellow flowers with brown spots. In fact, most Oncidium flowers are a variation of yellow and brown, although Oncidium ornithorhyncum produces pretty purple pink flowers, while Oncidium phalaenopsis and its relatives have beautiful white to red flowers, often spotted with pink. -

Histochemical and Phytochemical Analysis of Lamium Album Subsp

molecules Article Histochemical and Phytochemical Analysis of Lamium album subsp. album L. Corolla: Essential Oil, Triterpenes, and Iridoids Agata Konarska 1, Elzbieta˙ Weryszko-Chmielewska 1, Anna Matysik-Wo´zniak 2 , Aneta Sulborska 1,*, Beata Polak 3 , Marta Dmitruk 1,*, Krystyna Piotrowska-Weryszko 1, Beata Stefa ´nczyk 3 and Robert Rejdak 2 1 Department of Botany and Plant Physiology, University of Life Sciences, Akademicka 15, 20-950 Lublin, Poland; [email protected] (A.K.); [email protected] (E.W.-C.); [email protected] (K.P.-W.) 2 Department of General Ophthalmology, Medical University of Lublin, Chmielna 1, 20-079 Lublin, Poland; [email protected] (A.M.-W.); [email protected] (R.R.) 3 Department of Physical Chemistry, Medical University of Lublin, Chod´zki4A, 20-093 Lublin, Poland; [email protected] (B.P.); offi[email protected] (B.S.) * Correspondence: [email protected] (A.S.); [email protected] (M.D.); Tel.: +48-81-445-65-79 (A.S.); +48-81-445-68-13 (M.D.) Abstract: The aim of this study was to conduct a histochemical analysis to localize lipids, terpenes, essential oil, and iridoids in the trichomes of the L. album subsp. album corolla. Morphometric examinations of individual trichome types were performed. Light and scanning electron microscopy Citation: Konarska, A.; techniques were used to show the micromorphology and localization of lipophilic compounds and Weryszko-Chmielewska, E.; iridoids in secretory trichomes with the use of histochemical tests. Additionally, the content of Matysik-Wo´zniak,A.; Sulborska, A.; essential oil and its components were determined using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry Polak, B.; Dmitruk, M.; (GC-MS). -

Genome Relationships in the Oncidium Alliance A

GENOME RELATIONSHIPS IN THE ONCIDIUM ALLIANCE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HORTICULTURE MAY 1974 By Uthai Charanasri Dissertation Committee: Haruyuki Kamemoto, Chairman Richard W. Hartmann Peter P, Rotar Yoneo Sagawa William L. Theobald We certify that we have read this dissertation and that in our opinion it is satisfactory in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Horticulture. DISSERTATION COMMITTEE s f 1 { / r - e - Q TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF T A B L E S .............................................. iii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS...................................... iv INTRODUCTION ................................................ 1 REVIEW OF LITERATURE.................. 2 MATERIALS AND M E T H O D S ...................................... 7 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION ....................................... 51 Intraspecific Self- and Cross-Pollination Studies ........ Intrasectional Cross Compatibility within the Oncidium G e n u s ............................... 58 Intersectional and Intergeneric Hybridizations .......... 80 Chromosome Numbers ..................................... 115 K a r y o t y p e s ............................................ 137 Meiosis, Sporad Formation, and Fertility of Species Hybrids ............................. 146 Morphology of Species and Hybrids ..................... 163 General Discussion ................................... 170 SUMMARY -

Comparative Anatomy of the Floral Elaiophore in Representatives Of

Annals of Botany 112: 839–854, 2013 doi:10.1093/aob/mct149, available online at www.aob.oxfordjournals.org Comparative anatomy of the floral elaiophore in representatives of the newly re-circumscribed Gomesa and Oncidium clades (Orchidaceae: Oncidiinae) Małgorzata Stpiczyn´ska1, Kevin L. Davies2,*, Agata Pacek-Bieniek1 and Magdalena Kamin´ska1 1University of Life Sciences, Akademicka 15, 20-950 Lublin, Poland and 2School of Earth and Ocean Sciences, Cardiff University, Main Building, Park Place, Cardiff CF10 3AT, UK * For correspondence. E-mail [email protected] Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/aob/article/112/5/839/139696 by guest on 29 September 2021 Received: 19 March 2013 Returned for revision: 8 April 2013 Accepted: 14 May 2013 Published electronically: 24 July 2013 † Background and Aims Recently, molecular approaches have been used to investigate the phylogeny of Oncidiinae. This has resulted in the transfer of taxa previously considered to be species of Oncidium Sw. into Gomesa R. Br. and the re-circumscription of both genera. In this study, the structure of the floral elaiophore (oil gland) is described and compared for Gomesa echinata (Barb. Rodr.) M.W. Chase & N.H. Williams, G. ranifera (Lindl.) M.W. Chase & N.H. Williams, Oncidium amazonicum (Schltr.) M.W. Chase & N.H. Williams and O. oxyceras (Ko¨niger & J.G. Weinm.) M.W. Chase & N.H. Williams in order to determine whether phylogenetic revision is supported by differences in its anatomy. † Methods The floral elaiophore structure was examined and compared at three developmental stages (closed bud, first day of anthesis and final stage of anthesis) for all four species using light microscopy, fluorescence microscopy, scanning electron microscopy, transmission electron microscopy and histochemistry. -

2020-05 KOS Monthly Bulletin May 2020

THE MONTHLY BULLETIN OF THE KU-RING-GAI ORCHID SOCIETY INC. (Established in 1947) A.B.N. 92 531 295 125 May 2020 Volume 61 No. 5 Annual Membership : $15 single, $18 family . President : Dennys Angove 043 88 77 689 Committee Jessie Koh (Membership Secretary / Social Events) Secretary : Jenny Richardson (Culture Classes) Committee Herb Schoch (Liaison) Treasurer : Lina Huang Committee : Pauline Onslow (Member Support) Senior Vice President : tba Committee : Trevor Onslow (Guest Speakers) Junior Vice President : tba Committee : Chris Wilson (Library and Reference Sources) Editor (Hon volunteer) Jim Brydie Committee : Lee Payne (Sponsorship) Society mail to - PO box 1501 Lane Cove, NSW, 1595 Email – [email protected] web site (active link) : http:/kuringaiorchidsociety.org.au Next Meeting : * * * May Meeting CANCELLED With the present Corona virus situation, there will be no May meeting. The situation is constantly under review as to when we might resume. You will be advised immediately if there is a change. Wow, what a virtual benching – Wow, and Wow again. When virtual benching was first proposed I thought it might take members a little while to get on board with the idea. But no, there was terrific participation right from the start and a magical 6 page array of delicious, very professionally presented orchids, was created by Jenny. It included Cattleyas of all kinds and colours, Dendrobiums, Oncidiinae hybrids and rare species. It was just amazing. 14 different members contributed and if you count husbands and wives as separate it would be even more. The Fulchers provided a whole page of photos of orchids in flower from their collection, and even added a little info on each. -

MAOC Classification - January 1, 2020 (Alligned with MAOC Show Schedule July 2018)

MAOC Classification - January 1, 2020 (Alligned with MAOC Show Schedule July 2018) Name: Abbrev.: Class: Species: Hybrid: Abaxianthus (see Flickingeria) Abdominea (see Robiquetia) Aberrantia (see Pleurothallis) Abola (see Caucaea) Acacallis (see Aganisia) Acampe Acp. 68 69 Acampodorum (see Aracampe) Acampostylis Acy. 65 Acanthephippium Aca. 98 99 Acapetalum Acpt. 95 Acemannia Acm. 98 Aceras (see Orchis) Acianthera Acia. 92 Acianthus Aci. 98 99 Acinbreea Acba. 99 Acineta Acn. 98 99 Acinopetala (see Masdevallia) Aciopea Aip. 99 Acoridium (see Dendrochilum) Acostaea Asa. 92 Acriopsis Acr. 98 99 Acrolophia Apa. 81 Acronia (see Pleurothallis) Acropera (see Gongora) Acrorchis Arr. 98 99 Ada (see Brassia) Adacidium (see Brassidium) Adaglossum (see Brassidium) Adapasia (see Brapasia) Adelopetalum (see Bulbophyllum) Adenocalpa Adp. 69 Adenoncos Ade. 68 69 Adioda (see Brassioda) Adonclioda (see Brassidium) Aerachnochilus (see Paulsenara) Aerangaeris Arg. 58 Aeranganthes Argt. 58 Aerangis Aergs. 58 Aerangopsis Ags. 58 Aeranthes Aerth. 68 69 Aerasconetia (see Aeridovanda) Aeridachnanthe Aed. 66 Aeridachnis Aerdns. 66 Aeridanthe (see Aeridovanda) Aerides Aer. 66 Aeridisia (see Luisaerides) Aeriditis (see Aeridopsis) Aeridocentrum (see Aeridovanda) Aeridochilus Aerchs. 66 Name: Abbrev.: Class: Species: Hybrid: Aeridofinetia (see Aeridovanda) Aeridoglossum (see Renades) Aeridoglottis Aegts. 66 Aeridopsis Aerps. 66 Aeridopsisanthe (see Maccoyara) Aeridostachya (see Eria) Aeridovanda Aerdv. 69 Aeridovanisia Aervsa. 66 Aeridsonia (see Aeridovanda) Aeristomanda Atom. 66 Aeroeonia Aoe. 58 Aetheorhyncha 98 99 Agananthes Agths. 95 Aganax (see Pabanisia) Aganella All. 78 Aganisia Agn. 95 Aganopeste Agt. 93 Aganulophia Agp. 81 Agasepalum Agsp. 95 Agrostophyllum Agr. 98 99 Aitkenara Aitk. 95 Alamania Al. 16 25 Alangreatwoodara (see Propabstopetalum) Alantuckerara Atc. 95 Alaticaulia (see Masdevallia) Alatiglossum (see Gomesa) Alcockara (see Ledienara) Alexanderara (see Brassidium) Aliceara Alcra. -

Toskar Newsletter

TOSKAR NEWSLETTER A Quarterly Newsletter of the Orchid Society of Karnataka (TOSKAR) Vol. No. 5; Issue: ii; 2018 THE ORCHID SOCIETY OF KARNATAKA www.toskar.org ● [email protected] From the Editor’s Desk TOSKAR NEWSLETTER 21st June 2018 Well, monsoon is on right time, welcome! We had plenty EDITORIAL BOARD of pre-monsoon showers in the month of May. In the last (Vide Circular No. TOSKAR/2016 two months with good rains and humidity, the orchids Dated 20th May 2016) are happy and producing abundant fowers as we see from the display in the meetings and the posts in various forums. But with the rains and the wetness and often Chairman warm temperatures the combo sometimes is ideal for Dr. Sadananda Hegde onset of diseases in our cultivation, watch out for any such issues. Members We thought couple of activities from the TOSKAR side will Mr. S. G. Ramakumar help the hobbyists and other growers. In that direction, Mr. Sriram Kumar revival of the Training and Demonstration program is an important step. Several programs have been organized Editor by the society earlier for the growers at diferent levels Dr. K. S. Shashidhar but considering there is a constant need to update the care and culture techniques and also to make orchid growing more interesting, a series of T & D has been Associate Editor planned by the Society. The frst of the series with an Mr. Ravee Bhat overall view of cultural requirements of orchids and specifc to genus Oncidium was taken up on 9 June, 2018 at Lalbagh, Bangalore. -

RHS Orchid Hyrid Supplement 2010 April to June

8 Royal Horticultural Society Corporate Identity Guidelines 03.3 The RHS Master Logo Reproduction Colour Logo Mono Logo QUARTERLY SUPPLEMENT TO THE INTERNAT I ONAL REG is TER OF ORCH I D HYBR I D S The colour logo is the prefered option. Wherever Where effective reproduction of the colour logo (SANDER ’S Lis T ) possible, the Royal Horticultural Society logo should is not possible, the Royal Horticultural Society be reproduced in its colour version, either for print Mono Logos may be used. APRIL – JUNE 2010 REGISTRATIONS or in digital presentation. The preferred mono logo is the Reversed Colour breakdowns for the logo are detailed in the (White) logo. Colour section of these guidelines. Distributed with OrchidThe Review VO LUME 118, NUMBER 1291, SEP T EMBER 2010 NAME PARENTAGENEW O RCHID HYBRID S REGISTERED BY NAME PARENTAGE REGISTERED BY April – June 2010 REGISTRATIONS x Brassocatanthe Ward Bradeen Ctt. [Lc.] Loog Tone x B. nodosa W.Bradeen Supplied by the Royal Horticultural Society as International Cultivar Registration Authority for Orchid Hybrids x Brassocattleya Argentina Bicentenaria FCA C. Peckaviensis x B. nodosa E.A.Flachsland Jose’s Rose C. [Lc.] Love Knot x Bc. [Bl.] Morning Glory J.L.Hermo NAME PARENTAGE REGISTERED BY Tio Super C. Dayana (1966) x B. nodosa Rivera Rios (O/U) (O/U = Originator unknown) Bulbophyllum x Aeridovanda A-doribil Sunset Bulb. carunculatum x Bulb. claptonense B.Thoms Bensiri Aer. falcata x V. denisoniana A.Ngamkiatkhachorn Dark Star Bulb. Wilmar Galaxy Star x Bulb. echinolabium H.Schaible (R.Suwankerd) Jeff’s Houston Connection Bulb. Frank Smith x Bulb. -

Odontoglossum Alliance Newsletter

Odontoglossum Alliance Newsletter Volume 1 ___________________________________________________________________________ May 2016 In This Issue From Being the Same to Being Different by Stig Dalström Pages 1,3-7 Editorial Ramblings Page 2 A Note from the Editor Page 2 Obituaries: Alan Moon, by Brent Elliott Page 8 Professor Thomas Sheehan, by Andy Easton Page 9 Walter Off of Waldorf Orchids, by Andy Easton Page -10 Odontoglossums at the Orchid Zone by Bob Hamilton Pages 11-15 FROM BEING THE SAME TO BEING DIFFERENT, AND FROM BEING THE SAME TO BEING DIFFERENT AGAIN Stig Dalström 2304 Ringling Boulevard, unit 119, Sarasota FL 34237, USA Research Associate: Lankester Botanical Garden, University of Costa Rica, Cartago, Costa Rica National Biodiversity Centre, Serbithang, Thimphu, Bhutan [email protected]; www.wildorchidman.com The first documented collection of the orchid treat- ed initially in this article, was probably made by the German botanist Eduard Friedrich Pöppig around 1830, in the Cuchero area in Huanuco, Peru. It does not seem to have been scientifically described by Pöppig though because the earliest published record of this taxon was collected in an unknown locality somewhere in the New World tropics by the Polish traveler Josef von Warszewicz. It was described as Miltonia warszewiczii Rchb.f., by Heinrich Gus- tav Reichenbach in 1856. The same author then changed the name to Oncidium fuscatum Rchb.f., in 1863. Reichenbach obviously wanted to place this Figure A: Oncidium fuscatum, also known as Chamaeleorchis species in Oncidium but could not use the epithet warszewiczii. Photo by Angel Andreetta. Countinued on page 3 Odontoglossum Alliance Newsletter 1 May 2016 Editorial - Ramblings It would be great to hear from other growers with their concerns. -

MICROMORFOLOGIA E ANATOMIA FLORAL DAS SEÇÕES NEOTROPICAIS DE Bulbophyllum THOUARS (ORCHIDACEAE, ASPARAGALES): CONSIDERAÇÕES TAXONÔMICAS E EVOLUTIVAS

UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL PAULISTA unesp “JÚLIO DE MESQUITA FILHO” INSTITUTO DE BIOCIÊNCIAS – RIO CLARO PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM CIÊNCIAS BIOLÓGICAS (BIOLOGIA VEGETAL) MICROMORFOLOGIA E ANATOMIA FLORAL DAS SEÇÕES NEOTROPICAIS DE Bulbophyllum THOUARS (ORCHIDACEAE, ASPARAGALES): CONSIDERAÇÕES TAXONÔMICAS E EVOLUTIVAS ELAINE LOPES PEREIRA NUNES Tese apresentada ao Instituto de Biociências do Câmpus de Rio Claro, Universidade Estadual Paulista, como parte dos requisitos para obtenção do título de Doutor em Ciências Biológicas (Biologia Vegetal). Setembro - 2014 UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL PAULISTA unesp “JÚLIO DE MESQUITA FILHO” INSTITUTO DE BIOCIÊNCIAS – RIO CLARO PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM CIÊNCIAS BIOLÓGICAS (BIOLOGIA VEGETAL) MICROMORFOLOGIA E ANATOMIA FLORAL DAS SEÇÕES NEOTROPICAIS DE Bulbophyllum THOUARS (ORCHIDACEAE, ASPARAGALES): CONSIDERAÇÕES TAXONÔMICAS E EVOLUTIVAS ELAINE LOPES PEREIRA NUNES Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Alessandra Ike Coan Coorientador: Prof. Dr. Eric de Camargo Smidt Setembro - 2014 581.4 Nunes, Elaine Lopes Pereira N972m Micromorfologia e anatomia floral das seções neotropicais de Bulbophyllum Thouars (Orchidaceae, Asparagales) : considerações taxonômicas e evolutivas / Elaine Lopes Pereira Nunes. - Rio Claro, 2014 252 f. : il., figs., tabs. Tese (doutorado) - Universidade Estadual Paulista, Instituto de Biociências de Rio Claro Orientador: Alessandra Ike Coan Coorientador: Eric de Camargo Smidt 1. Anatomia vegetal. 1. Anatomia floral de Orchidaceae. 3. Dendrobieae. 4. Epidendroideae. 5. Labelo. 6. Nectário. 6. Osmóforos. -

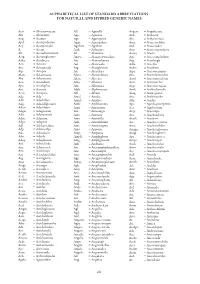

Orchid Name Abbreviations List

ALPHABETICAL LIST OF STANDARD ABBREVIATIONS FOR NATURAL AND HYBRID GENERIC NAMES Acw. = Aberconwayara All. = Aganella Angcst. = Angulocaste Abr. = Aberrantia Agn. = Aganisia Ank. = Anikaara Acp. = Acampe Agt. = Aganopeste Akr. = Ankersmitara Apd. = Acampodorum Agsp. = Agasepalum Anct. = Anoectochilus Acy. = Acampostylis Agubata = Agubata Atd. = Anoectodes A. = Aceras Aitk. = Aitkenara Ano. = Anoectogoodyera Ah. = Acerasherminium Al. = Alamania Anota = Anota Actg. = Aceratoglossum Agwa. = Alangreatwoodara Ayp. = Ansecymphyllum Acba. = Acinbreea Atc. = Alantuckerara Asg. = Anselangis Acn. = Acineta Aat. = Alaticaulia Aslla. = Ansellia Ain. = Acinopetala Atg. = Alatiglossum Asdm. = Ansidium Aip. = Aciopea Alc. = Alcockara Arpt. = Anteriocamptis Akm. = Ackermania Alxra. = Alexanderara Ahc. = Anterioherorchis Aks. = Ackersteinia Alcra. = Aliceara Atml. = Anteriomeulenia Aco. = Acoridium Alna. = Allenara Antr. = Anteriorchis Apa. = Acrolophia Aln. = Allioniara Atsp. = Anterioserapias Aro. = Acronia Alph. = Alphonsoara Anth. = Anthechostylis Acro. = Acropera Alv. = Alvisia Antg. = Antheglottis Ada = Ada Amal. = Amalia Anr. = Antheranthe Adh. = Adachilum Amals. = Amalias Alla. = Antilla Adg. = Adacidiglossum Amb. = Amblostoma Apr. = Apoda-prorepentia Adcm. = Adacidium Amn. = Amenopsis Aea. = Appletonara Adgm. = Adaglossum Am. = Amesangis Arcp. = Aracampe Adn. = Adamantinia Ams. = Amesara Ara. = Arachnadenia Adm. = Adamara Ame. = Amesiella Arach. = Arachnis Adps. = Adapasia Aml. = Amesilabium Act. = Arachnocentron Adl. = Adelopetalum Ami. = Amitostigma -

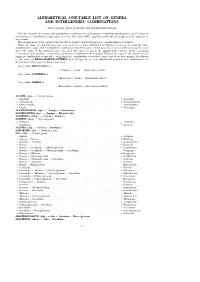

Alphabetical One-Table List of Genera and Intergeneric Combinations

ALPHABETICAL ONE-TABLE LIST OF GENERA AND INTERGENERIC COMBINATIONS (with parentage, where applicable, and standard abbreviations) This list contains the names and intergeneric combinations of all genera, including hybrid genera, which occur in current use in orchid hybrid registration as at 31st. December 2007, regardless of whether they appear in the main list of this volume. The arrangement of the entries is in One-Table format, and for intergeneric combinations is as follows: Under the name of each natural genus is entered (inset) each combination in which it occurs together with the name (following the = sign) of the intergeneric name which represents that combination. Each such combination appears once under the name of the natural genus concerned, the entries being in the alphabetical sequence of the remaining “constituent” genera which, in any entry, are themselves alphabetically arranged. Thus in the course of the whole list each bigeneric combination occurs twice, each trigeneric combination occurs three times, and so on. For example, in addition to the entry of BRASSOLAELIOCATTLEYA in bold type in its own alphabetical position, the combination for Brassolaeliocattleya appears three times, inset: Once under BRASSAVOLA as × Cattleya × Laelia = Brassolaeliocattleya Once under CATTLEYA as × Brassavola × Laelia = Brassolaeliocattleya Once under LAELIA as × Brassavola × Cattleya = Brassolaeliocattleya ACAMPE (Acp.) = Natural genus × Arachnis ................... =Aracampe × Armodorum .................. =Acampodorum × Rhynchostylis