Cambuskenneth Abbey and Its Estate: Lands, Resources and Rights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inchmahome Priory Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID:PIC073 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90169); Gardens and Designed Landscapes (GDL00218) Taken into State care: 1926 (Guardianship) Last reviewed: 2012 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE INCHMAHOME PRIORY We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2019 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH INCHMAHOME PRIORY SYNOPSIS Inchmahome Priory nestles on the tree-clad island of Inchmahome, in the Lake of Menteith. It was founded by Walter Comyn, 4th Earl of Menteith, c.1238, though there was already a religious presence on the island. -

Scenery ... History ... Mystery

... Scenery ... History ... Mystery www.witchescraig.co.uk Witches Craig The AA Campsite of the Year 2015 Winner for Scotland is situated at the foot of the Ochil Hills under the watchful gaze of the nearby National Wallace Monument. Visit Scotland have graded Witches Craig “an exceptional 5 star” touring park. Our park has won many other awards in recent years, including “Loo of the Year” and a David Bellamy “Gold” Conservation award. More pleasing than any award is the huge number of repeat customers and great reviews we receive in person and on review websites. We are particularly proud of the many hand drawn pictures of witches and toy witches that line the walls of our reception, gifted by families to mark a great stay. For almost forty years our family run, family friendly site has been a gateway to the Highlands and a base for exploring historic Stirling. Nearby you’ll also discover the scenic Trossachs, the rolling hills of Perthshire, the tranquil beaches of the Kingdom of Fife and much more. More than that, Witches Craig is in itself a destination – a peaceful, relaxing part of Central Scotland where every pitch has stunning views of the Ochil Hills and across to the historic city of Stirling. If you’re feeling active, you can access the Ochil Hills direct from the park, wander along an ancient roadway to the village of Blairlogie, or walk in the footsteps of William Wallace to the nearby Abbey Craig. For a more relaxing stroll you can see lots of wildlife around the Stirling University campus loch. -

The Gazetteer for Scotland Guidebook Series

The Gazetteer for Scotland Guidebook Series: Stirling Produced from Information Contained Within The Gazetteer for Scotland. Tourist Guide of Stirling Index of Pages Introduction to the settlement of Stirling p.3 Features of interest in Stirling and the surrounding areas p.5 Tourist attractions in Stirling and the surrounding areas p.9 Towns near Stirling p.15 Famous people related to Stirling p.18 Further readings p.26 This tourist guide is produced from The Gazetteer for Scotland http://www.scottish-places.info It contains information centred on the settlement of Stirling, including tourist attractions, features of interest, historical events and famous people associated with the settlement. Reproduction of this content is strictly prohibited without the consent of the authors ©The Editors of The Gazetteer for Scotland, 2011. Maps contain Ordnance Survey data provided by EDINA ©Crown Copyright and Database Right, 2011. Introduction to the city of Stirling 3 Scotland's sixth city which is the largest settlement and the administrative centre of Stirling Council Area, Stirling lies between the River Forth and the prominent 122m Settlement Information (400 feet) high crag on top of which sits Stirling Castle. Situated midway between the east and west coasts of Scotland at the lowest crossing point on the River Forth, Settlement Type: city it was for long a place of great strategic significance. To hold Stirling was to hold Scotland. Population: 32673 (2001) Tourist Rating: In 843 Kenneth Macalpine defeated the Picts near Cambuskenneth; in 1297 William Wallace defeated the National Grid: NS 795 936 English at Stirling Bridge and in June 1314 Robert the Bruce routed the English army of Edward II at Stirling Latitude: 56.12°N Bannockburn. -

Aberfoyle Post Shop

Free ISSUE 9 October 2003 Donations Welcome THE VOICE OF YOUR COMMUNITY Highlights of the 5 day programme: TV Chef to open Wed 22nd October 1230 hrs • Festival Opening-Scottish Wool Aberfoyle Centre inside Thurs 23rd October 1930 hrs P2 Mushroom Fest • Victorian Theatre - Scottish Wool One man & his Centre Restaurateur and TV Friday. 24th October 1930 hrs dog chef, Antonio Carluccio, • Fiddlers Rally & Candlelit Waterfall P3 Walk - David Marshall Lodge star of the highly-acclaimed Editorial • Dinner Dance featuring Ireland¹s BBC2 series on Cooking in Italy P4 Trevor Dixon Sound - Inchrie is to open the 3rd Aberfoyle Castle Hotel. Rangers Corner Mushroom Festival and launch Caprese in Buchanan Street, • Shenanigans Irish Night - Clachan th P5 his new book on picking and Glasgow on the Saturday and Sat 25 October, 1930 hrs CC Report Sunday in the Trossachs • Mushrooms and Shamrocks, A cooking with mushrooms, ‘The Feast of Irish Food, Drink and P6 Quiet Hunt’, at the Scottish Discovery Centre in the Music featuring Irish Dancers Owen McKee Wool Centre, Aberfoyle on village. Fungus forays are ‘Celtic Cousins’, The Trevor Dixon P7 Wednesday, 22 October at also a feature on these two Sound, & Mad Murphy - Forth Forest Theatre 1230 hrs. Members of the days, organised by Forest Inn. Enterprise from the David • Shenanigans Irish Night - Clachan P8 public are invited to join Signor Sun 26th October, 1830 hrs Comm Futures Carluccio for a tête-à-tête on Marshall Lodge and from the • Songs of Praise with the New P9 cooking, over a glass of red village by the National Park Scotland Singers - Gartmore House Prophecies wine and a fungi risotto. -

Fnh Journal Vol 15

Forth Naturalist and Historian, volume 15 1 the Forth Naturalist and Historian Volume 15 3 Global Warming: Reality or Bad Dream - S. J. Harrison 11 The Weather of 1991 - S. J. Harrison 19 Check List of Birds of Central Scotland - C. J. Henty and W. R. Brackenridge Book Review: Robert Louis Stevenson and the Highlands and Islands of Scotland - Louis Stott Forth Area Bird Report 1991 - C. J. Henty Environment notes: British Gas Environmental Issues series: CWS Cooperation for the Environment series: Project Brightwater Tropical Water Fern Azolla filiculoides at Airthrey Loch, Stirling University - Olivia Lassiere Rock Art: an Introduction: Preface to Van Hoek's Rock Art of Menteith - Lorna Main Prehistoric Rock Art of Menteith, Central Scotland - Maarten A. M. van Hoek Recent Books: Exploring Scottish History: Enchantment of the Trosschs: Concise History of the Church in Alloa; Alloa in Georgian Times People of the Forth (6): Saint Margaret, Queen of Scotland - Stewart M. Macpherson 86 Eighteenth Century Occasions: Communion Services in Georgian Stirlingshire - Andrew T. N. Muirhead 99 Quoiting in Central Scotland: Demise of a Traditional Sport - N. L. Tranter 116 Alloa: Port, Ships, Shipbuilding - Jannette Archibald 2 Forth Naturalist and Historian, volume 15 Published by the Forth Naturalist and Historian, a University/Central Regional Council collaboration, and an approved charity. The University, Stirling, 1992. ISSN 0309-7560 EDITORIAL BOARD Stirling University - D. McLusky (Chairman), D. Bryant, N. Dix and J. Proctor, Biology: B. J. Elliott, Education: S. J. Harrison, Environmental Science: N. Tranter, History. Central Region - M. Dickie (Vice Chairman) and N. Fletcher, Education Advisers: K. J. -

Holyrood Abbey Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC223 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM13031) Taken into State care: 1906 (Ownership) Last reviewed: 2014 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE HOLYROOD ABBEY We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2019 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH HOLYROOD ABBEY SYNOPSIS The Augustinian Abbey of Holyrood was founded by David I in 1128 as a daughter-house of Merton Priory (Surrey). By the 15th century the abbey was increasingly being used as a royal residence – James II was born there in 1430 - and by the time of the Protestant Reformation (1560) much of the monastic precinct had been subsumed into the embryonic Palace of Holyroodhouse. -

Polling Scheme –Parliamentary Election – Stirling County Constituency

LIST OF POLLING PLACES/STATIONS – 6 MAY 2021 SCOTTISH PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS Unit Station/ Box No No Polling Place SS105 Callander Kirk Hall 1 2 3 4 SS110 Strathyre Village Hall 5 SS115 Lochearnhead Village Hall 6 SS120 McLaren Hall, Killin 7 SS125 Balquhidder Village Hall 8 SS130 Crianlarich Village Hall 9 SS135 Muir Hall, Doune 10 11 SS140 Deanston Primary School 12 SS145 Blairdrummond Village Hall 13 SS150 Thornhill Community Hall 14 SS155 Port of Menteith Village Hall 15 File Name: M:\J Government & Democracy\J3 Elections\J3.3 Scottish Parliament\2021 DONT USE\Polling Places\Polling Scheme - Stirling.doc Unit Station/ Box No No Polling Place SS160 Gartmore Village Hall 16 SS165 Aberfoyle Nursery 17 (New polling place for 2021 – usually Discovery Centre, Aberfoyle) SS170 Kinlochard Village Hall 18 SS175 Brig O’Turk Village Hall 19 SS205 Gargunnock Community Centre 20 SS210 Kippen Village Hall 21 22 SS215 Buchlyvie Village Hall 23 SS220 Fintry Nursery 24 (New polling place for 2021 usually Menzies Hall, Fintry) SS225 McLintock Hall, Balfron 25 26 SS230 Drymen Public Library 27 SS235 Memorial Hall, Milton of Buchanan 28 SS240 Croftamie Nursery 29 File Name: M:\J Government & Democracy\J3 Elections\J3.3 Scottish Parliament\2021 DONT USE\Polling Places\Polling Scheme - Stirling.doc Unit Station/ Box No No Polling Place SS245 Killearn Church Hall 30 31 SS250 Strathblane Primary School 32 (New polling place for 2021 usually 33 Edmonstone Hall, Strathblane) 34 SS405 Cornton Community Centre 35 36 37 SS410 Logie Kirk Hall 38 39 40 SS415 Raploch -

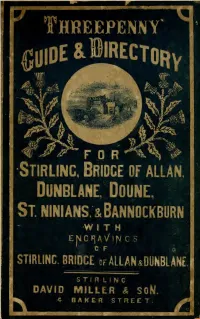

Threepenny Guide & Directory for Stirling, Bridge of Allan

Threepenny STIRLINC/BRIDCE Of ALLAN, Dunblane, DouNE, Si niniansjcBannockbiirn STIRLING. BRiiCE cf ALLAN sDUNBLANt STIRLING DAVID MILLER * SOW. ^ BAK&H STREE T >0A PATERSON & SONS' LONDON AND PARIS PIASOFOBTE, EARMOMM, ASD MFSIC S A L K S. The Largest Stock of Instruments in Scotland for Sale or Hire. PubUshers of the Celebrated GUINEA EDITION of the SCOTCH SONGS. SECOND-HAND PIANOFOKTES AND HARMONIUMS. PATERSON & SONS Have always on hand a Selection of COTTAGE, SQUARE, AND SEMI-GEAND PIANOFOKTES, SLIGHTLY USED. THE PATENT SIMPLEX PIANETTE, In Rosewood or Walnut, EIGHTEEN GUINEAS. This Wonderful Little Cottage Piano has a good touch, and stands well in Tune. FuU Compass (6i Octv.) HARMONIUMS BY ALEXANDRE, EVANS, and DEBAIN, From 6 to 85 GUINEAS. A Large Selection, both New and Segond-Hand. PATERSON 8c SONS, 27 GEORGE STREET, EDINBURGH; 152 BUCHANAN STREET, GLASGOW; 17 PRINCES STREET, PERTH. National Library Of S^^^^^^^^^^ -k ^^^^^ i^fc^^*^^ TO THE HONOURABLE THE OF THE ^v- Zey /Ma Digitized by the Internet Arciiive in 2010 witii funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/threepennyguided1866dire .. ... insriDExi- - Address, . Stirling, Stirling Castle, Back Walk, . Cemetery, . Ladies' Eock, Hospitals, Drummond's Tract Depot, Post-Office, . Stirling General Directory, Street Directory, Academies and Schools, Places of Worship, Sacramental Fast-Days, . Stirling Young Men's Christain Association, Trades and Professions Directory, Stirling Town Council, &c., Commissioners of Police, Sheriflf Court, Small Debt Court, Commissary Court, Justices of the Peace, Stirling Castle Officials, High School, School of Arts, Faculty of Writers, Parochial Board, Excise Office, Gas-Light Company, ... Water-Works, Athenseum Subscription Eeading-Eooru, Macfarlane Free Library, Newspapers, . -

Treasures Under Our Feet the Archaeology of Scotland’S Cities

www.archaeologyscotland.org.uk ISSUE 20 SUMMER 2014 Treasures under our feet The archaeology of Scotland’s cities Life and Bronze death Age jet in in Leith Dunragit - tram- works Urban structures & re-use CONTENTS Issue No 20 / Summer 2014 Editor’s Note ISSN 2041-7039 The next issue will be on the theme of Religion and Religious Published by Archaeology Scotland, editorial recent projects Sites. We also welcome articles on more general topics, community Suite 1a, Stuart House, 04 From the Director 19 Recent work by GUARD Archaeology at Eskmills, Station Road, projects, SAM events and research Musselburgh EH21 7PB Cambuskenneth, Dunragit and Yarrowford projects, as well as members’ Tel: 0845 872 3333 letters. Members are particularly Fax: 0845 872 3334 encouraged to send letters, short Email: info@archaeologyscotland. features news articles, photos and opinions org.uk 05 24 relating to Scottish archaeology Scottish Charity SC001723 Brewers and Backlands Glasgow Exhibition; AGM and Members’ Day at any time for inclusion in our 08 25 Company No. 262056 Life and Death in the City Community Heritage Conference; Accord ‘Members’ Section’. 12 Searching for Stirling’s Secrets Project 15 Structures and Urban Archaeology 26 Free Training; 60 Second Interview If you plan to include something Cover picture 28 in the next issue, please contact Excavation of a tanning tank at Scottish Archaeology Month 2014 the Holyrood North site © CFA the editor in advance to discuss Archaeology Ltd requirements, as space is usually at books a premium. We cannot guarantee Editing and typesetting to include a particular article in a Sue Anderson, 30 Reviews: Glasgow - A History; Historic Bute. -

An Account of the Excavations at Cambuskenneth Abbey 1864Y Coloney B Ma

I. AN ACCOUNT OF THE EXCAVATIONS AT CAMBUSKENNETH ABBEY 1864Y COLONEY B MA . R JAMEN I SI L . ALEXANDERE S , K.C.L.S., F.S.A. SOOT., &c. (PLATE IV.) Abbee Th f Cambuskennethyo , founde n 114 di Davi y f Scotb 7o . dI - land, stoopeninsula n do rivee th f r ao Forth littld an , e more tha milna e idirecna t line fro e towm th Stirlingf no ferrA . y require crossee b o st d to reach the remains of the venerable pile. So complete has been the destruction of the Church of St Mary of Cambuskennet disciplee th y hb Johf o s n Kno 1559n xi , tha s s sitit t ewa now founquite b o edt covered with greensward, where cows grazedA . white-washed cottage and some old elms were on the south side, and behind the n extensivwalle a m th f o s e eth orcharde s easth wa tn O . windin e e fielcentrg th th river d f n o eI appeare . a dmoun d slightly t somi n raisedo e d thoran , n bushe conjectureds s: here wa t i , , stooe dth higa broke s h wa altar n t wesr i archfo f , o t , e forminentrancth w no ge to a small enclosed cemetery in which are the tombstones of a few of the e peopldistrictth f o e . This arch, pointed, enriched with deeplt cu y mouldings, the capitals of broken shafts and trellis carving, was evidently the principal or western door of the church. -

Fnh Journal Vol 17

CORRIGENDA FN&H Volume 17 P54—with apologies—the Bold Heading BOOK NOTES/REVIEWS should not precede the article THE NORTHERN EMERALD but follow it above HERITAGE WOOD. the Forth Naturalist Volume 17 Historian 3 Mineral Resource Collecting at the Alva Silver Mines - Brian Jackson 5 The Weather of 1993 - S. J. Harrison 13 Alpine Foxtail (Alopecurus Trin.) in the Ochils - R. W. M. Corner 15 Woodlands for the Community - Alastair Seaman 22 Environmental History - an emergent discipline 23 Forth Area Bird Report 1993 - C. J. Henty 54 The Northern Emerald: an Addition to the Forth Valley Dragonfly Fauna - John T. Knowler and John Mitchell: Hermitage Wood: Symposium 55 Mountain Hares in the Ochil Hills - Alex Tewnion 63 Clackmannan River Corridors Survey - Cathy Tilbrook 67 Book Reviews and Notes (Naturalist) 69 Norway: Author/Reviewers Addresses 70 New Light on Robert Louis Stevenson - Louis Stott 74 R. L. Stevenson and France; Stevenson Essays of Local Interest 75 Bridge of Allan: a Heritage of Music; and its Museum Hall - Gavin Millar and George McVicar 89 Blairlogie: a Short History of Central Scotland's First Conservation village - Alastair Maxwell-Irving 94 Trial of Francis Buchanan 1746 - George Thomson 95 People of the Forth (3) Part 2: David Bruce: Medical Scientist, Soldier, Naturalist - G. F. Follett 103 The Ancient Bridge of Stirling: a New Survey - R. Page 111 Launching Forth: The River - Alloa to Stirling - David Angus 119 Archaeology Notes - Lorna Main and Editor 121 Book Reviews and Notes (Historical) 2 Forth Naturalist and Historian, volume 17 Published by the Forth Naturalist and Historian, a University/Central Regional Council collaboration, and an approved charity. -

Eg Phd, Mphil, Dclinpsychol

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Scottish Augustinians: a study of the regular canonical movement in the kingdom of Scotland, c. 1120-1215 Garrett B. Ratcliff Doctor of Philosophy School of History, Classics, and Archaeology University of Edinburgh 2012 In memory of John W. White (1921-2010) and Nicholas S. Whitlock (1982-2012) Declaration I declare that this thesis is entirely my own work and that no part of it has previously been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification. N.B. some of the material found in this thesis appears in A. Smith and G. Ratcliff, ‘A Survey of Relations between Scottish Augustinians before 1215’, in The Regular Canons in the Medieval British Isles, eds. J. Burton and K. Stöber (Turnhout, 2011), pp. 115-44. Acknowledgements It has been a long and winding road.