Interview with John L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

August-September 07 Issue.Indd

Episcopal Diocese of S.C. • P.O. Box 20127 • Charleston, SC 29413-0127 • Phone: (843) 722-4075 • Email: [email protected] • Web: www.dioceseofsc.org CHANGE SERVICE REQUESTED The Episcopal Diocese of South Carolina August/September 2007 Volume CXII, No. 4 Bishop’s Election August 4 No Petition Candidates Submitted he deadline for the submission mediately following the celebration Tof petition candidates for the of Holy Communion the convention Bishop’s Election of the Diocese of will convene to elect the XIV Bishop South Carolina has come and gone. of South Carolina. We request that No petitions were submitted. each mission and parish submit the The special Bishop’s Election, names of their specially elected lay as previously called by the Stand- delegates to the Diocesan offi ce as ing Committee on June 9, will be soon as possible. begin at 10:00 a.m. on August 4, at St. James Church, James Island. The Rev. J. Haden McCormick Registration of clergy and lay del- President, Standing Committee egates will begin at 8:00 a.m. Im- Photo: Bill Murton Coastal Crisis Chaplaincy Serves During Devastating Fire and Its Aftermath By the Rev. Rob Dewey, Senior Chaplain, Coastal Crisis Chaplaincy ave you ever been part of an When I arrived on the scene, I saw event that you knew would chaos. I reported to the Command Post Hforever change your life, the and was informed that it was feared life of your community, and perhaps nine firefighters were missing. As even the life of your country? Most of fi refi ghters continued to fi ght the blaze, us refl ect back to “9-11 experiences,” word and reality of the loss began to such as President Kennedy’s assassi- spread. -

Seeds of Hope Prophetic Witness at Diocesan Convention

THE WINTER 2014 Episcopal News EpiscopalWWW.EPISCOPALNEWS.COM SERVING THE SIX-COUNTY News DIOCESE OF LOS ANGELES Seeds of Hope Prophetic witness at Diocesan Convention THE EPISCOPAL NEWS Winter 2014 1 FROM THE BISHOP Sharing God’s Peace join my sister bishops and JOHNNY BUZZERIO JOHNNY our families in wishing you J. Jon Bruno I and your family and friends a Bishop of Los Angeles blessed Christmastide and a won- derful new year as once again we welcome the Prince of Peace to be By J. Jon Bruno born in new ways in our lives. In the coming year, let us do all we can to work for peace with justice locally, regionally and in- ternationally — remembering that true peace begins as each of us cul- tivates peace within our own lives and homes, and then our work- The Church of the Nativity marks the site of Jesus’ birth in Bethlehem. places, schools and congregations. My own prayers for peace include the Holy Lands considered the oldest church in Christendom. where Jesus our Savior was born. Each time I have This is a model for Christians everywhere, call- visited Bethlehem and the Church of the Nativity ing all of us — as we honor and share the diverse marking Christ’s birthplace, I have appreciated the gifts of our unique traditions — to come together ways in which monastic communities of three in common prayer and common cause to welcome faith traditions — the Armenian Apostolic, everyone hospitably into the good news of God’s the Greek Orthodox, and the Roman Cath- love for all. -

The Board of the Archives of the Episcopal Church

ARCHIVES The Board of the Archives of the Episcopal Church CONTENTS A. Membership B. Summary of the Board's Work C. Financial Report D. Proposed Resolutions E. Objectives and Goals for the New Triennium F. Proposed Budget for the Coming Triennium G. Proposed Resolution for Budget Appropriation H. Report of the Archivist I. Appendix: The Administration and Care of Our Historical Resources A. MEMBERSHIP The Right Reverend Scott Field Bailey, Chair, San Antonio, TX (1991) The Right Reverend Duncan M. Gray, Vice-Chair, Jackson, MS (1991) The Right Reverend James H. Ottley, Balboa, Panama (1994) The Reverend Donald Hungerford, Treasurer, Odessa, TX (1994) The Reverend Frank E. Sugeno, Austin, TX (1991) The Reverend J. Robert Wright, New York, NY (1991) Dr. David B. Gracy, Austin, TX (1991) Mrs. Frances Swinford Barr, Lexington, KY (1994) MrS. Barbara Smith, Anchorage, AK (1991) The Very Reverend Durstan McDonald, Austin, TX (ex officio) Mr. Mark J. Duffy, Archivist, Austin, TX (ex officio) B. SUMMARY OF THE BOARD'S WORK The purpose of the Board is to set policy for the Archives regarding the records and historical collections of the Episcopal Church, to elect the Archivist of the Episcopal Church, and to set forth the terms and conditions with regard to the work of the Archivist. The full Board met twice in the past triennium as did the Executive Committee of the Board. The meetings were held at the Archives of the Episcopal Church in Austin, Texas. The Board reviewed progress made on all three of its major goals for the past triennium: the selection and appointment of a new Archivist, the computerization of the Archives, and the employment of a professional staff. -

The Episcopal Diocese of Pittsburgh the Search for the Eighth Bishop Diocesan 2011 Diocesan Profile Welcome!

The Episcopal Diocese of Pittsburgh The Search for the Eighth Bishop Diocesan 2011 Diocesan Profile Welcome! The Search/Nominating Committee and the people of the Episcopal Diocese of Pittsburgh of the Episcopal Church prayerfully offer this profile in hope that persons considering a call to be bishop of our diocese, or persons considering submitting the name of a potential candidate, will learn about us and our values, experiences, hopes, and what we discern to be God’s will. Our last decade has been a decade of challenge. The challenge is not yet over but we are confident that God has a plan and, even now, has identified a person who is fit to lead us in our next chapter of growth and rebuilding. As we spoke with members of the diocese in their parishes, we heard their sense of optimism and hope. As we prayed together as a committee and studied the responses to our surveys, the way forward has become clearer to us and, we hope, to those of you who may discern a call to respond. We hope that this profile gives you a snapshot of our Vibrant Episcopal Communities United in Christ and the wonderful region of the country in which we live and work. The Search/Nominating Committee will receive names from August 15 to September 30, 2011. Instructions for submitting names may be found at the end of this profile. Our recommendations for a slate of nominees will be submitted to the Standing Committee before January 15, 2012. Following the publication of that slate, there will be a three-week period for nomination by petition before the slate is final. -

St. Andrew's Episcopal Church the Fourth Sunday in Lent And

St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church The Fourth Sunday in Lent And Commemoration of Bishop Barbara Clementine Harris Home Eucharist, Rite III March 14, 2021 Things to know about Zoom - WELCOME all! Wherever you’re joining us from, we’d love to meet each other and talk after the service. Just accept the invitation to go into breakout rooms to socialize with others! - Everyone is muted during the service to preserve sound quality. You’re still encouraged to pray and sing along at home! The Rt. Rev. Barbara C. Harris June 12, 1930 – March 13, 2020 Born in Philadelphia, Bishop Barbara Harris is the first woman to be consecrated a bishop in the Episcopal Church, and the entire Anglican Communion. As a laywoman, she served as the crucifer at the ordination of the Philadelphia Eleven – the first ordination of women in the Episcopal Church – which took place at the Church of the Advocate in Philadelphia. She is remembered as a powerful advocate for justice within our church, constantly challenging us “never to be instruments of our own or another’s oppression.” Bishop Barbara was a woman of great truth and wit who inspired, challenged, and was held dear by Episcopalians across the country. With her death coming at the beginning of lockdown, it was decided to hold her funeral when it was safe to re-gather (more than 8,000 people attended her consecration as Suffragan Bishop of the Diocese of Massachusetts in 1989). To date, no funeral has been held. The current bishops of Massachusetts issued a call for churches to commemorate Bishop Barbara on this first anniversary of her death. -

Barbara Harris Visit 1989 Robin Bartlett Denison University

Denison University Denison Digital Commons Looking Back, Looking Forward Women's and Gender Studies 1989 Barbara Harris Visit 1989 Robin Bartlett Denison University John Jackson Denison University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.denison.edu/lookingback Recommended Citation Bartlett, Robin and Jackson, John, "Barbara Harris Visit 1989" (1989). Looking Back, Looking Forward. 9. http://digitalcommons.denison.edu/lookingback/9 This Letter is brought to you for free and open access by the Women's and Gender Studies at Denison Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Looking Back, Looking Forward by an authorized administrator of Denison Digital Commons. December 16, 1988 The Rev. Barbara C. Harris Diocese of Massachusetts 13d Tremont Street Boston.. MA 02 111 Dear Rev. Harris: Next year we at Denison University will celebrate an institutional milestone: the Tenth Anniversary of our pioneering graduation requirement in Women's Studies/Minority Studies. Both Black Studies, Women's Studies, and me College Chaplain, would be honored and excited if you could help us celebrate this event by delivering a public lecture or sermon on campus. Your achievements, coupled with the regrettable opposition to your elevation to the office of Suffragan Bishop, make you a singularly appropriate choise as our keynote speaker. We want to mark both how far the cause of human rights and acceptance has progressed in the United States and yet how far we still have to go. We also want our Tenth Anniversary to mark a renewed educational and spiritual commitment on the part of Denison to the ideal of tolerance of diversity. -

Nominee Information 13 FALL 2012 Crossing the Finish Line

Nominee Crossing the Finish Line Information 13 & Netsforlife® 4 ARIZONA EPISCOPALIAN // VOLUME 3 // ISSUE 4 FA L L 2 012 AZ DIOCESAN EVENTS OCTOBER - DECEMBER 2012 OCTOBER NOVEMBER [continued] 5 First Friday Art Walk 11 Veteran’s Day 6PM | TRINITY CatHEDRAL IN PHOENIX ARIZONA EPISCOPALIAN // VOLUME 3 // ISSUE 4 Bishop’s Visitation 6 Diocesan Women’s Ministries Gathering ST. ANDREW’S IN TUCSON 8:30AM | TRINITY CatHEDRAL IN PHOENIX 12 Southern Arizona Deacons Meeting THE EpISCOpal DIOCESE OF ARIZONA 7 Bishop’s Visitation 12 PM | GRACE ST. PAUL’S IN TUCSON Established in 1959, The Episcopal ST. JOHN’S IN WILLIAMS Diocese of Arizona has 25,000 22-23 Thanksgiving members in 12,500 households in 8 Southern Arizona Deacons Meeting DIOCESAN OFFICE CLOSED 64 congregations. We are part of 12PM | GRACE ST. PAUL’S IN TUCSON The Episcopal Church and the 30-12/2 Men’s Retreat worldwide Anglican Communion. 12 Celebration of New Ministry of The Rev. Julie O’Brien CHAPEL ROCK, PRESCOTT inside this issue 7PM | ST. STEPHEN’S IN PHOENIX DIOCESAN HOUSE FALL 2012 DECEMBER 114 W. Roosevelt Street 13 Quiet Day Phoenix, AZ 85003-1406 9:30AM | ST BARNABAS IN SCOTTSDALE 7 First Friday Art Walk 602-254-0976 phone 800-420-1500 toll free Diocesan Events left Farmers Market of Free Food 6PM | TRINITY CatHEDRAL IN PHOENIX 602-495-6603 fax 10AM | ST. LUKE’S IN PHOENIX Contents 1 azdiocese.org 8 Quiet Day E-pistle 2 14 Bishop’s Visitation 9:30AM | ST BARNABAS IN SCOTTSDALE THE BISHOP OF ARIZONA 52nd Diocesan Convention: Realizing God’s Dreams ST. -

What Chances? Reuse

VOL.66 NO.6 JUNE 1983 publication. and What Chances? reuse for Michael T. Klare George F. Kennan required Susan B. Anthony Permission DFMS. / Church Episcopal the of I Archives 2020. I Copyright LETTERS could hold hearings was the first Convention's strong Standing Commis- Monday. Then both Houses had to act sion on the Church in Metroplitan Areas, on the proposal before Program Budget it may just be powerful enough to cut the T UtilBf and Finance went to press with their ground from under Jack Woodard's budget on Thursday. That was not eloquent plea "Look out for the Spirit possible. and wonderful surprises." And that Jubilee Ministry Wronged It is a matter of deep concern to many would be darkness, indeed. that the present national budget process The Rt. Rev. John E. Hines As always, it was good to read retired puts the real power almost completely in Black Mountain, N.C. Presiding Bishop John Hines' thoughts the hands of the Presiding Bishop. If a in the March issue of THE WITNESS. Standing Commission is trying to put Parenti Article Biased But about the Jubilee Ministry, the into the proposed budget something the record needs setting straight. He says, 815 staff does not favor, it might as well I found Nat Pierce's article in the Feb- "The forces that strove to help extend or save its energy. It will lose the battle ruary issue most thought-provoking. I recreate a socially active ministry of the before the General Convention ever con- have known Nat from several General publication. -

University Job Opportunities

The Sewanee Mountain MESSENGER Vol. XXX No. 20 Friday, June 6, 2014 County School Board St. Andrew’s Chapel Sewanee Requests 7-Cent Community Centennial Mass Property Tax Increase Invited to Presiding Bishop to Preach and Celebrate Th e Most Rev. Dr. Katharine Jeff erts Schori, Presiding Bishop and Primate In an eff ort to solve the continuing budget crisis in the Franklin County of the Episcopal Church of the United States, will preach and celebrate the School system, the board of education has requested a 7-cent property tax Take Survey Holy Eucharist at a special Centennial Mass at St. Andrew’s-Sewanee School’s increase. Th e Franklin County Commission will have to decide whether to In conjunction with the com- St. Andrew’s Chapel on Saturday, June 7. Th e presiding bishop’s visit coincides accept this recommendation. munity meetings in Sewanee with the school’s Alumni Weekend [see story on page 6] and is in tribute to Th e school board and Director of Schools Rebecca Sharber have been strug- regarding the downtown planning the Centennial Celebration of St. gling to have a budget for the 2014–15 year that would have a $3 million fund process, a survey is being con- Andrew’s Chapel. balance. With the proposed property tax increase, the fund balance would be ducted so that the broader com- Th e service begins at 9:30 a.m. approximately $2.4 million. munity can share their thoughts on Saturday. Th e Chapel doors will At the April 7 meeting of the school board, the draft budget showed a $1.2 and opinions. -

158Th Diocesan Convention Passes 9 Resolutions, Elects 29 Offices by Sean Mcconnell That Has Caused Isolation and Division Within the One Clergy and One Lay

an edition of THE EPISCOPAL CHURCH IN CHURCH THE SAN FRANCISCO BAY AREA December 2007 PACIFICNEWS VOL. 18 No. 12 158th Diocesan Convention Passes 9 Resolutions, Elects 29 Offices By Sean McConnell that has caused isolation and division within the one clergy and one lay. The Rev. Nina Pickerrell communion. (Deacon), and Ron Johnson were elected to the Standing he 158th Convention of the Diocese of California, “To follow either extreme is to put at risk the great Committee’s class of 2011. Both Pickerrell and Johnson held at San Francisco’s Grace Cathedral on Friday riches of our Anglican heritage, through which the Lord are from Grace Cathedral. and Saturday, October 19 and 20, passed nine T has blessed us so greatly over the centuries,” Ndungane The Ecclesiastical Court’s class of 2010 added two resolutions and elected diocesan officers and deputies to told the convention Eucharist. members of the clergy and one lay person. They are the the 2009 General Convention of the Episcopal Church to “We must not lose this inheritance, if we are serious Rev. Nancy Eswein (Deacon), the Rev. Paul Burrows be held in Anaheim, California. about being faithful to the Lord, as he has been faithful (priest), and Karen Valentia Clopton.. The week leading up to convention included a Taizé to us. The Board of Directors added two clergy members service for diocesan unity held at St. Paul’s, Walnut “At the heart of Anglicanism is not one single way and one layperson, although unlike the offices above, Creek, and town hall meetings around the diocese of being Christian. -

Download Seed & Harvest | Fall/Winter 2020

Seed & Harvest TRINITY SCHOOL FOR MINISTRY FALL/WINTER 2020 Celebrating the consecration of Church of Christ our Peace (CCOP) in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, in conjunction with the 25th Anniversary Celebration of the Deanery of Cambodia. This building also houses the National Office of the Deanery. In this issue, we share good news about the growth of the six deaneries in Southeast Asia. See the full article on page 9, written by the Rev. Canon Yee Ching Wah, who is a good friend of Trinity School for Ministry, and supporter of our mission. Registration for 2021 January InterTerm ends soon! See pages 16-18 for details. IN THIS ISSUE Seed & Harvest VOLUME 43 | NUMBER 1 3 From the Dean and President 4 Hope: An Abiding Grace PRODUCTION STAFF 5 Planting Churches: Being Doers of the Word [email protected] Executive Editor 6 Planting Hope Through Prayer The Very Rev. Dr. Henry L. Thompson III 9 Anglican Mission in Southeast Asia [email protected] 12 Church Planting in Anathoth General Editor 14 Serving God May Require Some Pruning, Uprooting, Mary Lou Harju and Planting [email protected] 16 January InterTerm 2021 Layout and Design Alexandra Morra 19 Meeting the Need for Theological Education in Latin America SOLI DEO GLORIA 20 Alumni News 22 Formation...at a Distance 23 For the Proclamation of the Gospel 24 Giving Generously During the Pandemic 25 Stewardship and Generosity in an Age of Coronavirus Dean and President 26 In Memoriam The Very Rev. Dr. Henry L. Thompson III 29 New Opportunities to Serve [email protected] 29 From Our Bookshelf Academic Dean Dr. -

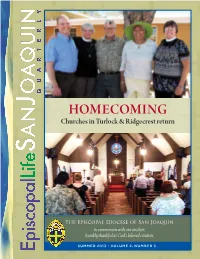

Homecoming Churches in Turlock & Ridgecrest Return

HOMECOMING Churches in Turlock & Ridgecrest return The Episcopal Diocese of San Joaquin In communion with one another, humbly thankful as God’s beloved creation summer 2013 • Volume 2, Number 3 The diocese of san Joaquin Governance StandinG committee depuTies To General convenTion Clergy: Clergy Deputies: 2016 The Rev. Glenn Kanestrom Christ the King, Riverbank C1 The Rev. Canon Mark Hall St. Anne’s, Stockton 2015 The Rev. Suzy Ward, C2 The Rev. Luis Rodriguez Church of the Saviour, Hanford (Secretary) St. Paul’s, Visalia C3 The Rev. Glenn Kanestrom Christ the King, Riverbank 2014 The Rev. Michele Racusin, C4 The Rev. Kathryn Galacia St. Francis, Turlock (President) Holy Family, Fresno CA1 The Rev. Michele Racusin Holy Family, Fresno 2013 The Rev. John Shumaker St. Matthew’s, San Andreas CA2 The Rev. Paul Colbert St. Raphael’s, Oakhurst and Holy Trinity, Madera Lay: CA3 The Rev. Kathleen West St. Paul’s, Modesto 2016 Juanita Weber St. Anne’s, Stockton 2015 Stan Boone Holy Family, Fresno Lay Deputies: 2014 Richard Cress St. John’s, Lodi L1 Nancy Key Holy Family, Fresno 2013 Richard Jennings Holy Family, Fresno L2 Cindy Smith St. Brigid’s Bakersfield L3 Bill Latham Christ the King, Riverbank L4 Jan Dunlap St. Brigid’s Bakersfield diocesan council LA1 Judith Wood St.Paul’s, Visalia LA2 Marilyn Metzgar Grace, Bakersfield NOTHERN DEANERY Clergy: 2014 The Rev. Basil Mattews, St. Clare, Priest In Charge Lay: 2015 Louise McCoskey, Christ the King, Riverbank depuTies To province viii synod CENTRAL DEANERY The Rev. Paul Colbert St. Raphael’s, Oakhurst and Clergy: 2013 The Rev.