Master Thesis the Two Faces of Corporate Brands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Companies That Do Test on Animals

COMPANIES THAT DO TEST ON ANIMALS Frequently Asked Questions Why are these companies included on the 'Do Test' list? The following companies manufacture products that ARE tested on animals. Those marked with a are currently observing a moratorium (i.e., current suspension of) on animal testing. Please encourage them to announce a permanent ban. Listed in parentheses are examples of products manufactured by either the company listed or, if applicable, its parent company. For a complete listing of products manufactured by a company on this list, please visit the company's Web site or contact the company directly for more information. Companies on this list may manufacture individual lines of products without animal testing (e.g., Clairol claims that its Herbal Essences line is not animal-tested). They have not, however, eliminated animal testing from their entire line of cosmetics and household products. Similarly, companies on this list may make some products, such as pharmaceuticals, that are required by law to be tested on animals. However, the reason for these companies' inclusion on the list is not the animal testing that they conduct that is required by law, but rather the animal testing (of personal-care and household products) that is not required by law. What can be done about animal tests required by law? Although animal testing of pharmaceuticals and certain chemicals is still mandated by law, the arguments against using animals in cosmetics testing are still valid when applied to the pharmaceutical and chemical industries. These industries are regulated by the Food and Drug Administration and the Environmental Protection Agency, respectively, and it is the responsibility of the companies that kill animals in order to bring their products to market to convince the regulatory agencies that there is a better way to determine product safety. -

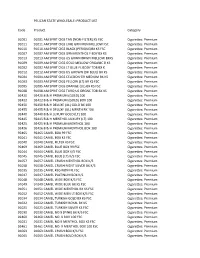

(NON-FILTER) KS FSC Cigarettes: Premiu

PELICAN STATE WHOLESALE: PRODUCT LIST Code Product Category 91001 91001 AM SPRIT CIGS TAN (NON‐FILTER) KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91011 91011 AM SPRIT CIGS LIME GRN MEN MELLOW FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91010 91010 AM SPRIT CIGS BLACK (PERIQUE)BX KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91007 91007 AM SPRIT CIGS GRN MENTHOL F BDY BX KS Cigarettes: Premium 91013 91013 AM SPRIT CIGS US GRWN BRWN MELLOW BXKS Cigarettes: Premium 91009 91009 AM SPRIT CIGS GOLD MELLOW ORGANIC B KS Cigarettes: Premium 91002 91002 AM SPRIT CIGS LT BLUE FL BODY TOB BX K Cigarettes: Premium 91012 91012 AM SPRIT CIGS US GROWN (DK BLUE) BX KS Cigarettes: Premium 91004 91004 AM SPRIT CIGS CELEDON GR MEDIUM BX KS Cigarettes: Premium 91003 91003 AM SPRIT CIGS YELLOW (LT) BX KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91005 91005 AM SPRIT CIGS ORANGE (UL) BX KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91008 91008 AM SPRIT CIGS TURQ US ORGNC TOB BX KS Cigarettes: Premium 92420 92420 B & H PREMIUM (GOLD) 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92422 92422 B & H PREMIUM (GOLD) BOX 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92450 92450 B & H DELUXE (UL) GOLD BX 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92455 92455 B & H DELUXE (UL) MENTH BX 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92440 92440 B & H LUXURY GOLD (LT) 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92445 92445 B & H MENTHOL LUXURY (LT) 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92425 92425 B & H PREMIUM MENTHOL 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92426 92426 B & H PREMIUM MENTHOL BOX 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92465 92465 CAMEL BOX 99 FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91041 91041 CAMEL BOX KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91040 91040 CAMEL FILTER KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 92469 92469 CAMEL BLUE BOX -

WWD Beauty Inc Top 100 Shows, China Has Been An

a special edition of THE 2018 BEAUT Y TOP 100 Back on track how alex keith is driving growth at p&g Beauty 2.0 Mass MoveMent The Dynamo Propelling CVS’s Transformation all the Feels Skin Care’s Softer Side higher power The Perfumer Who Dresses the Pope BINC Cover_V2.indd 1 4/17/19 4:57 PM ©2019 L’Oréal USA, Inc. Beauty Inc Full-Page and Spread Template.indt 2 4/3/19 10:25 AM ©2019 L’Oréal USA, Inc. Beauty Inc Full-Page and Spread Template.indt 3 4/3/19 10:26 AM TABLE OF CONTENTS 22 Alex Keith shares her strategy for reigniting P&G’s beauty business. IN THIS ISSUE 18 The new feel- 08 Mass EffEct good facial From social-first brands to radical products. transparency, Maly Bernstein of CVS is leading the charge for change. 12 solar EclipsE Mineral-based sunscreens are all the rage for health-minded Millennials. 58 14 billion-Dollar Filippo Sorcinelli buzz practicing one Are sky-high valuations scaring away of his crafts. potential investors? 16 civil sErvicE Insights from a top seller at Bloomies. fEaTUrES Francia Rita 22 stanD anD DElivEr by 18 GEttinG EMotional Under the leadership of Alex Keith, P&G is Skin care’s new feel-good moment. back on track for driving singificant gains in its beauty business. Sorcinelli 20 thE sMEll tEst Lezzi; Our panel puts Dior’s Joy to the test. 29 thE WWD bEauty inc ON THE COvEr: Simone top 100 Alex Keith was by 58 rEnaissancE Man Who’s on top—and who’s not— photographed Meet Filippo Sorcinelli, music-maker, in WWD Beauty Inc’s 2018 ranking of by Simone Lezzi Keith photograph taker, perfumer—and the world’s 100 largest beauty companies exclusively for designer to the Pope and his entourage. -

THE SUPREME COURT of APPEAL of SOUTH AFRICA JUDGMENT Not Reportable Case No: 553/2019

THE SUPREME COURT OF APPEAL OF SOUTH AFRICA JUDGMENT Not reportable Case No: 553/2019 In the matter between: KONI MULTINATIONAL BRANDS (PTY) LTD APPELLANT and BEIERSDORF AG RESPONDENT Neutral citation: Koni Multinational Brands (Pty) Ltd v Beiersdorf AG (553/19) [2021] ZASCA 24 (19 March 2021) Coram: CACHALIA, MAKGOKA AND SCHIPPERS JJA AND SUTHERLAND AND UNTERHALTER AJJA Heard: 19 November 2020 Delivered: This judgment was handed down electronically by circulation to the parties’ representatives by email. It has been published on the Supreme Court of Appeal website and released to SAFLII. The date and time of hand-down is deemed to be 10h00 on 19 March 2021. Summary: Unlawful competition – passing-off – men’s shower gel – whether reputation of respondent’s get-up of predominant colour combination of blue, white and silver protectable – whether appellant’s product confusingly similar – respondent’s get-up used extensively – its products the leading brand in its category and holding majority share of shower gel market – overall appearance and format of appellant’s product confusingly similar – appeal dismissed. 2 ________________________________________________________________ ORDER ________________________________________________________________ On appeal from: Gauteng Division of the High Court, Johannesburg (Fisher J sitting as court of first instance): 1 The appeal is dismissed with costs, including the costs of two counsel, where so employed. 2 The Registrar of this Court is directed to forward a copy of this judgment to the Legal Practice Council, Pretoria, to investigate the circumstances in which the respondent’s attorneys, Mr Gerard du Plessis and Ms Elizabeth Serrurier, failed to disclose Ms Serrurier’s association with the respondent’s attorneys to the Gauteng Division of the High Court, Johannesburg and this Court, when filing an affidavit by her, purportedly as a member of the public, and to take whatever steps it deems appropriate in the light thereof. -

Unilever Annual Report and Accounts 2019 and Is an Exact Copy of the Printed Document Provided to Unilever’S Shareholders

Disclaimer This is a PDF version of the Unilever Annual Report and Accounts 2019 and is an exact copy of the printed document provided to Unilever’s shareholders. Certain sections of the Unilever Annual Report and Accounts 2019 have been audited. These are on pages 87 to 152, and those parts noted as audited within the Directors’ Remuneration Report on pages 66 to 72. The maintenance and integrity of the Unilever website is the responsibility of the Directors; the work carried out by the auditors does not involve consideration of these matters. Accordingly, the auditors accept no responsibility for any changes that may have occurred to the financial statements since they were initially placed on the website. Legislation in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands governing the preparation and dissemination of financial statements may differ from legislation in other jurisdictions. Except where you are a shareholder, this material is provided for information purposes only and is not, in particular, intended to confer any legal rights on you. This Annual Report and Accounts does not constitute an invitation to invest in Unilever shares. Any decisions you make in reliance on this information are solely your responsibility. The information is given as of the dates specified, is not updated, and any forward-looking statements are made subject to the reservations specified in the cautionary statement on the inside back cover of this PDF. Unilever accepts no responsibility for any information on other websites that may be accessed from this site by hyperlinks. Unilever Unilever Annual Report and Accounts 2019 and Accounts Annual Report Unilever Purpose-led, future-fit Unilever Annual Report and Accounts 2019 Unilever Annual Report and In this report Accounts 2019 This document is made up of the Strategic Report, the Governance Strategic Report Report, the Financial Statements and Notes, and Additional How our strategy is delivering value for our stakeholders Information for US Listing Purposes. -

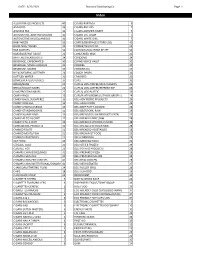

3/22/2021 Standard Distributing Co. Page 1 ALLIGATOR ICE

DATE: 3/22/2021 Standard Distributing Co. Page 1 Index ALLIGATOR ICE PRODUCTS 40 CIGARS-PARTAGA 6 ANTACIDS 33 CIGARS-PHILLIES 7 ARIZONA TEA 31 CIGARS-SWISHER SWEET 7 AUTOMOTIVE-ADDITIVES/FLUIDS 35 CIGARS-U.S. CIGAR 7 AUTOMOTIVE-MISCELLANEOUS 36 CIGARS-WHITE OWL 7 BABY NEEDS 33 COFFEE/BEVERAGE (STORE USE) 40 BAND AIDS/ SWABS 33 COFFEE/TEA/COCOA 23 BAR SUPPLIES 34 COLD/SINUS/ALLERGY RELIEF 33 BARBEQUE/HOT SAUCE 22 CONDENSED MILK 23 BATTERIES/FLASHLIGHTS 34 CONDOMS 34 BEVERAGE, CARBONATED 30 CONVENIENCE VALET 32 BEVERAGE, MISCELLANEOUS 31 COOKIES 20 BEVERAGE, MIXERS 30 COOKING OIL 23 BLEACH/FABRIC SOFTENER 24 COUGH DROPS 33 BOTTLED WATER 31 CRACKERS 20 BOWLS/PLATES/UTENSILS 37 CUPS 36 BREAD/BUNS 27 CUPS & LIDS-COFFEE/JAVA CLASSICS 36 BREAD/DOUGH MIXES 22 CUPS & LIDS-COFFEE/REFRESH EXP 36 CAKE/FROSTING MIXES 22 CUPS & LIDS-PLASTIC 36 CANDY-BAGS 15 CUPS/PLATES/BOWLS/UTENSILS(RESELL) 24 CANDY-BAGS, SUGARFREE 16 DELI-ADV PIERRE PRODUCTS 29 CANDY-KING SIZE 12 DELI-ASIAN FOOD 29 CANDY-MISCELLANEOUS 13 DELI-BEEF PATTY,COOKED 28 CANDY-STANDARD BARS 11 DELI-BEEF/PORK, RAW 28 CANDY-XLARGE BARS 13 DELI-BREAD/DOUGH PRODUCTS FRZN 29 CANDY-45 TO 10 CENT 12 DELI-BREADED BEEF,RAW 28 CANDY-5 TO 2 CENT 12 DELI-BREADED CHICKEN,COOKED 28 CANNABIDIOL PRODUCTS 32 DELI-BREADED CHICKEN,RAW 28 CANNED FRUITS 21 DELI-BREADED VEGETABLES 28 CANNED MEATS/FISH 21 DELI-BREAKFAST FOOD 29 CANNED VEGETABLES 21 DELI-CORNDOGS 29 CAT FOOD 23 DELI-MEXICAN FOOD 29 CEREALS, COLD 23 DELI-OTHER FROZEN 29 CEREALS, HOT 23 DELI-POTATO PRODUCTS 28 CHAMPS CHKN BOXES/BAGS 41 DELI-PREPARED -

Working Commissary List

Page 1 WCCW TEC RESIDENTIAL & IPU COMMISSARY LIST UPDATED: September 1, 2021 PRICES, ITEMS, FLAVORS, AND WEIGHTS MAY CHANGE WITHOUT NOTICE - TAX RATE 8.5% Date: Last First DOC # Unit / Cell# Signature: Code Qty Product Price Limit Code Qty Product Price Limit ENVELOPES SKIN CARE - TAXABLE 8067 Prefranked Envelope-Indigent $ 0.61 10/Month 1306 Medicated Skin Cream, 4 oz $ 1.05 Combined 8068 Prefranked Envelope $ 0.61 40/Order 1326 St. Ives Apricot Scrub, 6 oz $ 3.19 4/Order DEBTABLE PROPERTY ITEMS*- per DOC Policy 440.000 - TAXABLE 1300 Three in One Body Lotion, 12 oz - H $ 4.03 4615 Reading Glasses - +1.50 $ 1.89 1301 Hypoallergenic Lotion, 16 oz $ 2.20 4620 Reading Glasses - +2.00 $ 1.89 1303 Baby Oil - H, 6.5 oz $ 1.07 4625 Reading Glasses - +2.50 $ 1.89 Combined 1305 Crawford Cocoa Butter Lotion, 4oz $ 0.47 4630 Reading Glasses - +3.00 $ 1.89 1/Year 1309 Suave Cocoa Butter Lotion, 10 oz $ 2.20 4635 Reading Glasses - +3.50 $ 1.89 1310 Cococare Cocoa Butter Stick, 1 oz $ 1.56 Combined 4640 Reading Glasses - +4.00 $ 1.89 1311 Petroleum Jelly, 7.5 oz $ 1.27 2/Order OTC - DEBTABLE - Restrictions per DOC Policy 650.040 - TAXABLE 1312 Ambi Complexion Bar, 3.5 oz $ 1.99 1892 Sunscreen, Banana Boat - SPF 30, 1 oz $ 0.99 2/Order 1313 Oil of Olay, 4 oz $ 9.07 4501 Muscle Rub, 1.25 oz $ 0.85 1/M 1315 Infuzed Lotion w/ Aloe, 15 oz $ 1.84 4502 Artificial Tears, 0.5 oz $ 1.33 1/M 1316 Suave Advanced Therapy Lotion, 10 oz $ 2.20 4506 Clotrimazole Topical, 1 oz $ 0.98 1/M 1333 Baby Powder, 15 oz - H $ 1.03 4507 Hydrocortisone 1% Cream, 28 gm $ 1.03 -

5.99 $5.99 $5.49 $5.49

No Waste Only the Best ¢ Broccoli 99 Crowns FROM OUR SEAFOOD DEPARTMENT Trident Premium Seafood Entrees Fresh ¢ $5.99 Express SAVE 5.99 50¢-$I.50 Salad 99 10–14 oz. pkg. Blends SAVE $3.00LB. 10–12 oz. bag. •Italian •American •Hearts of Romaine Jumbo 16/20 ct EZ Peel Shrimp $$ 9.999.99 LB. FROM OUR DELI Dierbergs Signature SAVE $3.00LB. Bavarian-Style Ham Hot House Grown $$ Red Ripe ¢ 5.995.99 Tomatoes 99 99LB. on the Vine SAVE Mayrose Hoffman’s $2LB. Hard Super Sharp Salami Cheddar Cheese LIMIT 4 $$ Farmland 6.996.99 Sliced Bacon $ SAVE Jennie-O $ $ 3.59 SAVE I.50LB. Honey Mesquite $2.40 Turkey Breast 12 oz. pkg. $$5.495.49 LIMIT 4 Frito Lay FROM OUR BAKERY •Baked Lay’s •Sunchips SAVE SAVE •Rold Gold Pretzels 92¢ Strawberry $I Cream Dessert Horns $ Shells SAVE I.79 ¢¢ $$I.49I.49 $ 7777 I.50 6.25–16 oz. pkg. 4 ct. pkg. 4 ct. pkg. Fish Eye Wines $3.97 750 ml. btl. Limit 48 btls. All 7 varieities included! All discounts included in this price. Yellow Tail, Beringer or Robert Mondavi Woodbridge $$44..9797 750 ml. btl. Limit 60 btls. Over 25 selected varieties. Excluding Reserves, Private selections or Founders Estates. Selected varieties only. All discounts included in this price. This pull-out ad section good at all stores, This pull-out ad section good at all stores, Thursday, May 15, 2014. We reserve the right to limit. PULL OUT HERE! Thursday, May 15, 2014. We reserve the right to limit. -

Internships, Jobs and More YOUR MONTHLY SOURCE for CAREER ADVICE, EVENTS & OPPORTUNITIES

April, 2018 51st Issue— STU Career Services Newsletter Internships, Jobs and More YOUR MONTHLY SOURCE FOR CAREER ADVICE, EVENTS & OPPORTUNITIES IN THIS EDITION, YOU WILL FIND: EVENTS & JOBS & SPOTLIGHT AROUND CAMPUS RESOURCES OPPORTUNITIES INTERNSHIPS 1 CAREER SERVICES MESSAGE Although hard to believe, the Spring semester is coming to an end. Now that the summer is rapidly approaching, I encourage you to consider doing an internship to get experience in your field of study while, hopefully, making some money as well. At St. Thomas University we make it extremely easy for you to have access to, apply, and find an internship. We have the industry’s latest career management tool (Handshake) to ease the process for you. Simply create an account on Handshake by logging into https://stu.joinhandshake.com and using your STU username and password as the credentials to access the system. Upload your résumé and a cover letter to get started. Currently, there are 1,618 internships posted in Handshake. By location, 100 internships are located in Miami, and 30 internships are in Ft. Lauderdale. Employers include the Miami Marlins, Florida Department of Transportation, and HBO Latin America, to name a few. What are you waiting for? Apply today online or through Cristina C. López, MBA, M.A., Handshake’s iPhone app! Director of Career Services Editorial Team: Publisher and Editor-in-Chief, Cristina C. López, MBA, M.A. Associate Editor, David Hong, Class of 2021 Marketing Design, Carlos Gamarra, Class of 2018 Newsletter Design, Federico Moronell, B.B.A. ‘17 MEET OUR TEAM! Lawrence Treadwell IV, Associate Professor, Director of the Library & Student Success Center APRIL 2018, 51st Issue Cristina C. -

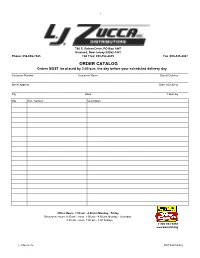

Fall Catalog for Web Site

1 760 S. Delsea Drive, PO Box 1447 Vineland, New Jersey 08362-1447 Phone: 856-692-7425 Toll Free: 800-552-2639 Fax :800-443-2067 ORDER CATALOG Orders MUST be placed by 3:00 p.m. the day before your scheduled delivery day Customer Number Customer Name Day of Delivery Street Address Date of Delivery City State Taken by Qty Item number Description Office Hours: 7:00 am - 4:00 pm Monday - Friday Showroom Hours: 8:30 am - noon, 1:00 pm - 4:30 pm Monday - Thursday 8:30 am - noon, 1:00 pm - 3:00 Fridays 1-800-934-3968 www.wecard.org L J Zucca, Inc. 2007 Fall Catalog 2 Table of contents Pages Automotive Air Fresheners, Antifreeze, Gas Cans, Maps, Motor Oil, Starting Fluid, Windshiel 70-71 Beverages 35-39 Bottle water, Carbonated drinks, Sports drinks, Juices, Cigars 9-14 Boxes, Little Cigars, Packs, Premium, Twin Packs Cigarettes 4-8 25's, 100's, 120's, Generic, King's, Non Filter, Premium, Specialty Confections - Candy 22-32 Candy - Concession, Fundraiser, Gum, King Size, Mints, Nostalgic, Novelty, Peg-bags, Regular, Wrapped, Un-wrapped Dairy 84-86 Butter, Cheese, Dinners, Juice, Meats, Puddings Food Service 46-48 Cappuccino Mixes, Coffee Service, Fountain Syrups, Gallon & Bulk Items Frozen 87-89 Bagels, Cakes, Dinners, Juice, Meats, Pizza, Vegetables, Waffles, Grocery 72-84 Baby Needs, Cookies, Coffee. Condiments, Cleaning items, Laundry supplies, Pasta, Pet Food, Rice, Tea, Vegetables General Merchandise 19-21 Batteries, Duct Tape, Phone Cards, Shoe Polish, Super Glue Health & Beauty Care 56-70 Aspirin, Cold & Cough remedies, Eye care, Shampoo, Toiletries Paper 49-55 Aluminum Foil, Cups, Napkins, Plates, Towels, Trash Bags, Toilet Tissues Snacks 42-46 Chips, Cookies, Meat Snacks, Nuts, Popcorn, Pretzels, Tobacco & Tobacco Accessories 14-18 Chewing, Cigarette Papers, Lighters, Matches, Pipe, Plug, Roll-Your-Own, Snuff, Wraps, L J Zucca, Inc. -

Smart Score Book the Smart Score Book the Smart Score 3000

SMART SCORE BOOK THE SMART SCORE BOOK THE SMART SCORE 3000 SMART MISSION “IT’S TIME TO BRING SMART PRODUCTS TO THE ENTIRE GLOBE. CHANGING THE WORLD IS A BIG GOAL, BUT IT’S ONE THAT WE ARE UP FOR!” OUR HISTORY IS ROOTED IN CLEAN Over 30 years ago, we started with a single product: Shampoo. In the process of creating our first product, we had to make a “Smart” descision: Either use conventional product ingredients or strive for something safer. We took the road never travelled. We chose safer for our customers, ourselves and the environment. Instead of formulating with SLS (Sodium Lauryl Sulfate), we opted for more sound ingredients. And, while we didn’t know it at the time, that “Smart” decision would go on to define our entire company. Each one of our products is safe, affordable, and accessible to you and your home—and best of all, they perform better than those store‐bought chemfests. We are a company that stands for honesty, integrity, and transparency. We don’t believe in compromise, so we’ve taken a stance against potentially harmful ingredients. Each year, our Lifestyle Advisory Board reviews and makes recommendations on our usage of every single ingredient in our warehouse. If it doesn’t pass that test, we don’t use it. We won’t compromise on safety and take pride in our ability to keep you out of harm’s way. SLS was the first ingredient to which we said no, starting a list of ingredients we refuse to use that now numbers in the thousands and continues to grow. -

A Fact-Sheet on Unilever's Cosmetics

THE HIDDEN COSTS OF SKIN-DEEP BEAUTY Fact sheet on Unilever’s cosmetics Few are indifferent to the images of glamorous models endorsing a widening range of cosmetic products, designed to tweak, twist, stretch, shrink, moisturise and colour the human anatomy. These images seduce middle-class consumers and shape their thoughts, dreams and demands. Most people are aware of the underlying motive – the profit of cosmetics companies. But conscience, even caution, is a poor match for the hypnotic effect of these advertisements. Hindustan Unilever, India’s largest cosmetics seller and manufacturer, is one corporation that thrives in this business. For Unilever to sell its products, it works at a deeper level - shaping and selling public notions of beauty itself. Sadly, much of its marketing carries a racist tinge. Notwithstanding attempts to advertise using ‘ethnic’ models and settings to capture third- world markets, the predominant notion of beauty sold by Unilever is one of fairness. The sale of products such as Fair And Lovely and Emami’s Fair And Handsome relies on selling and exploiting aspirations to fair and spotless skin. The real beauty in accepting oneself and others, warts and all, is ignored, meant only for Ugly Ducklings who’ve given up on the fairness dream. Most alarming, Unilever’s products carry immense costs often hidden from the unsuspecting consumer. These costs cannot always be measured in or mitigated by money. Several of Unilever’s cosmetics have been found to contain dangerous levels of toxic chemicals with long-term impacts on consumers’ health. Further, communities and the environment at the site of production are also affected – for example, inadequately protected workers who are exposed to these toxic chemicals at the manufacturing site, and voiceless animals experimented upon.