C:\Documents and Settings\Alan Smithee\My Documents\MOTM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stibnite Gold Project

STIBNITE GOLD PROJECT PAYETTE & BOISE NATIONAL FORESTS INTERMOUNTAIN REGION August 22, 2018 STIBNITE MINING DISTRICT, PAYETTE NATIONAL FOREST, KRASSEL RANGER DISTRICT Regarding Locatable Minerals , 36 CFR 228, Subpart A: requires the Forest Service to: "Where conflicting interests Respond to a mining plan, evaluate that plan must be reconciled, the Consider requirements to minimize adverse effects to the extent feasible question shall always be Comply with applicable laws, regulations and answered from the stand- standards for environmental protection point of the greatest good of Assure appropriate reclamation Further respond by following National Environmental the greatest number in the Policy Act (NEPA) processes. long run." - James Wilson, Secretary Per 36 CFR 228.4, the Forest Service is required to take of Agriculture, 1905 in a letter to Gifford action to ensure that “operations are conducted so as, Pinchot, 1st Chief of the Forest Service. where feasible, to minimize adverse environmental impacts on National Forest surface resources. 1 Table of Contents Project Context STIBNITE GOLD Project Location 4 Mining History at Stibnite 5 PROJECT Who is Midas Gold 6 Stibnite Plan of Operations PAYETTE & BOISE NATIONAL Proposed Mining Plan of FOREST - INTERMOUNTAIN REGION Operations 7 Open Pit Mining 8 Anadromous Fish - Tunnel 9 Inventoried Roadless Areas - Why is this project of interest to many Access and Powerline 10 people and organizations? Facilities During Mining Operations 10 5 million recoverable ounces of gold x -

40 Common Minerals and Their Uses

40 Common Minerals and Their Uses Aluminum Beryllium The most abundant metal element in Earth’s Used in the nuclear industry and to crust. Aluminum originates as an oxide called make light, very strong alloys used in the alumina. Bauxite ore is the main source aircraft industry. Beryllium salts are used of aluminum and must be imported from in fluorescent lamps, in X-ray tubes and as Jamaica, Guinea, Brazil, Guyana, etc. Used a deoxidizer in bronze metallurgy. Beryl is in transportation (automobiles), packaging, the gem stones emerald and aquamarine. It building/construction, electrical, machinery is used in computers, telecommunication and other uses. The U.S. was 100 percent products, aerospace and defense import reliant for its aluminum in 2012. applications, appliances and automotive and consumer electronics. Also used in medical Antimony equipment. The U.S. was 10 percent import A native element; antimony metal is reliant in 2012. extracted from stibnite ore and other minerals. Used as a hardening alloy for Chromite lead, especially storage batteries and cable The U.S. consumes about 6 percent of world sheaths; also used in bearing metal, type chromite ore production in various forms metal, solder, collapsible tubes and foil, sheet of imported materials, such as chromite ore, and pipes and semiconductor technology. chromite chemicals, chromium ferroalloys, Antimony is used as a flame retardant, in chromium metal and stainless steel. Used fireworks, and in antimony salts are used in as an alloy and in stainless and heat resisting the rubber, chemical and textile industries, steel products. Used in chemical and as well as medicine and glassmaking. -

Antimony Data Sheet

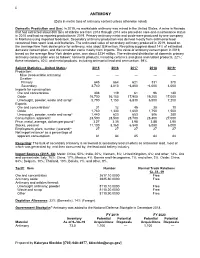

22 ANTIMONY (Data in metric tons of antimony content unless otherwise noted) Domestic Production and Use: In 2019, no marketable antimony was mined in the United States. A mine in Nevada that had extracted about 800 tons of stibnite ore from 2013 through 2014 was placed on care-and-maintenance status in 2015 and had no reported production in 2019. Primary antimony metal and oxide were produced by one company in Montana using imported feedstock. Secondary antimony production was derived mostly from antimonial lead recovered from spent lead-acid batteries. The estimated value of secondary antimony produced in 2019, based on the average New York dealer price for antimony, was about $34 million. Recycling supplied about 14% of estimated domestic consumption, and the remainder came mostly from imports. The value of antimony consumption in 2019, based on the average New York dealer price, was about $234 million. The estimated distribution of domestic primary antimony consumption was as follows: nonmetal products, including ceramics and glass and rubber products, 22%; flame retardants, 40%; and metal products, including antimonial lead and ammunition, 39%. Salient Statistics—United States: 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019e Production: Mine (recoverable antimony) — — — — — Smelter: Primary 645 664 621 331 370 Secondary 3,740 3,810 e3,800 e4,000 4,000 Imports for consumption: Ore and concentrates 308 119 61 96 140 Oxide 16,700 16,100 17,900 19,200 17,000 Unwrought, powder, waste and scrap1 5,790 7,150 6,830 6,500 7,200 Exports: Ore and concentrates1 31 -

Minerals of Bismuthinite-Stibnite Series with Special Reference to Horobetsuite from the Horobetsu Mine, Hokkaido, Japan*

MINERALOGICAL JOURNAL VOL . 1, No. 4, pp. 189-197, JUNE, 1955 MINERALS OF BISMUTHINITE-STIBNITE SERIES WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO HOROBETSUITE FROM THE HOROBETSU MINE, HOKKAIDO, JAPAN* KITARO HAYASE Institute of Mining, Faculty of Science and Engineering , Waseda University. ABSTRACT Horobetsuite occurs associated with free sulphur and iron sulphide minerals, in the sulphur deposit of Horobetsu Mine. The chemical formula of horobetsuite has been determined as (Bi, Sb)2S3. The molecular ratio of Bi2S3 to Sb2S3 varies between 9:11 and 13:7. The mineral is intermediate between bismuthinite and stibnite in lattice constant, specific gravity, optical behaviour and etching reac tion. The data obtained reveal the mineral to be a new species belonging to the bismuthinite-stibnite series. A new mineral name, horobetsuite, is proposed for the mineral of the series which should have the molecular ratio of Bi2S3 to Sb2S3 between 7:3 and 3:7. Introduction The writer1) once reported the results of the study of a Bi-Sb sul phide mineral that occurred at the Horobetsu mine, and suggested that it might represent a solid solution of bismuthinite and stibnite. The slight fluctuation observed of the molecular ratio of Bi2S3 to Sb2S3 has prompt us to a further study. Occurrence of horobetsuitel) The Horobetsu mine in which horobetsuite occurs is located at Sobetsu Village, Usu County, in the vicinity of Muroran, Hokkaido, Japan. (Fig. 1) * Read at the Annual Meeting of the Mineralogical Society of Japan held in Tokyo on June 4, 1954. 190 Minerals of Bismuthinite-Stibnite Series Fig. 1. Sulphur ore body of Horobetsu Mine. -

Antimony Deposits of Alaska

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FRANKLIN K. LANE, Secretary UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, Director Bulletin 649 ANTIMONY DEPOSITS OF ALASKA BY ALFRED H. BROOKS WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1916 CONTENTS. Page. Introduction.............................................................. 5 Mining developments and production........................................ 6 Geographic distribution....................:............................... 8 Geology.................................................................. .9 Occurrence of the antimony deposits................................... 9 Country rock......................................................... 9 Ore bodies............................................................ 10 Classification.................................-.----.-------------- 10 Siliceous gold-bearing stibnite lodes................................ 10 Stibnite-cinnabar lodes. ............................................ 12 Stibnite-galena deposits........................................... 12 Influence of coxmtry rock........................................... 13 Vertical distribution of ores........................................ 13 Oxidation......................................................... 13 Age of mineralization............................................... 14 Localities.................................................. 1............... 17 Fairbanks district. ..................................................... 17 Development of antimony deposits................................. -

STIBNITE GOLD PROJECT Valley County, Idaho

STIBNITE GOLD PROJECT Valley County, Idaho REFINED PROPOSED ACTION MODPRO2 Midas Gold Idaho, Inc. PO Box 429 13181 Hwy 55 December 2020 Donnelly, ID 83615 STIBNITE GOLD PROJECT REFINED PROPOSED ACTION – MODPRO2 Summary This document describes Midas Gold Idaho, Inc.’s (Midas Gold’s) proposed further refinements of the Stibnite Gold Project (SGP) Plan of Restoration and Operations (PRO) (Midas Gold, 2016) and presents Midas Gold’s updated proposed action, the ModPRO21. The ModPRO2 was developed to further reduce potential environmental impacts of the SGP in alignment with Midas Gold’s Core Values as set out in the PRO (Section 2), Conservation Principles (PRO Section 2), its Sustainability Goals (PRO Section 2.4) and its Environmental Goals (PRO Section 6.2). Project refinements included in the ModPRO2: (1) are supported by udpated data and analysis that identify opportunities to reduce potential environmental impacts; (2) address persistent potential environmental impacts not sufficiently ameliorated or reduced by project refinements included in the original ModPRO; (3) are informed by public and reviewing agencies’ comments on the DEIS, and; (4) align with the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and all applicable Federal, State and Local regulations and permit requirements. The ModPRO2 also aligns with the project development approach in Midas Gold’s Feasibility Study (FS) (M3, 2020). The ModPRO2 is presented in three sections and an appendix: • Section 1 describes the evolution of the ModPRO2 in the context of the original proposed action (the PRO) and alternatives evaluated in the SGP Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) including the ModPRO (DEIS Alternative 2). • Section 2 provides the justification and approach for refinements to components of the SGP that result in the ModPRO2. -

Selective Extraction of Mercury and Antimony from Cinnabar-Stibnite Ore

Bureau of Mines Report of Investigations 5243 SELECTIVE EXTRACTION OF MERCURY AND ANTIMONY FROM CINNABAR-STIBNITE ORE BY E. G. ERSPAMER AND R. R. WELLS p i _I -- United States Department of the Interior- September 1956 ... 1-- - SELECTIVE EXTRACTION OF MERCURY AND ANTIMONY FROM CINNABAR-STIBNITE ORE « BY E. G. ERSPAMER AND R. R. WELLS * * * * * * * * * Report of Investigations 5243 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Fred A. Seaton, Secretary BUREAU OF MINES Marling J. Ankeny, Director Work on manuscript completed November 1955. The Bureau of Mines will welcome reprinting of this paper, provided the following footnote acknowledgment is made: "Reprinted from Bureau of Mines Report of Investigations 5243." September 1956 SELECTIVE EXTRACTION OF MERCURY AND ANTIMONY FROM CINNABAR-STIBNITE ORE by E. G. Erspamerl/ and R. R. Wells2J/ CONTENTS Page Summnary .......................... ,............. 1 Introduction ................... eww=...e=,e, .* .., 1 Concentration of mercury ores ............................ 2 Previous laboratory studies of Red Devil ore ................. 4 Current investigations .................................. .... 5 Scope *............. ............. ....... 5 Mineral-dressing studies ................................. 5 Character of the ore .............................. 5 Physical ..................... ........... 5 Chemical ........................ ........... 5 Preliminary tests ..................... 6 Screen analysis ................................ 6 Heavy-liquid test .............................. 6 Methods -

10800 Realgar

10800 Realgar Chemical composition : As4S4 C.I. 77085, Pigment Yellow 39 Realgar is the natural orange-red sulphide of arsenic. It is closely related chemically and associated in nature with orpiment. The two minerals are often found in the same deposits. Realgar occurs as a minor constituent in certain ore veins associated with orpiment and other arsenic minerals, with stibnite, lead, gold and silver. It is found in Romania, the former Czechoslovakia, and the former Yugoslavia, Greece, Germany, Italy, Corsica and the western United States. The name is derived from the Arabic rahj al ghar, powder of the mine. The Latin term was sandarach and De Mayerne who was writing in the seventeenth-century referred to it as rubis d'orpiment. Realgar has been found on a few works by Tintoretto and from Bulgarian icons dating from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance. Realgar has also been reported on Indian sixteenth- to seventeenth-century paintings and an eleventh- to thirteenth-century manuscript from Central Asia. Realgar appears to be less permanent and is known to change to orpiment after long exposure to light. Chinese realgar figurines from the eighteenth-century had oxidized to orpiment and arsenious oxide (Daniels). The chemical and physical properties are similar to orpiment. It belongs to the same crystal system (monoclinic). Its color is orange or an orange-red by transmitted light but usually many yellow particles of orpiment can also be seen. The particles of mineral realgar are usually granular, coarse to fine and have a resinous to greasy luster. Excerpts from: Artist's Pigments Vol.3 Elisabeth West Fitzhugh (editor) and Painting Materials Rutherford J. -

Antimony 2016

2016 Minerals Yearbook ANTIMONY [ADVANCE RELEASE] U.S. Department of the Interior April 2019 U.S. Geological Survey Antimony By Kateryna Klochko Domestic survey data and tables were prepared by Hoa P. Phamdang, statistical assistant. In 2016, no marketable antimony was mined in the Smelter.—The United States had only one antimony smelter, United States. A mine in Nevada that had extracted about operated by U.S. Antimony Corp. (USAC) (Thompson Falls, 800 metric tons (t) of stibnite ore from 2013 through 2014 MT) in Montana. The smelter processed intermediate antimony was placed on care-and-maintenance status in 2015 and had products from Australia, Canada, and Mexico; recovered no reported production in 2016. Primary antimony metal precious metals; and produced antimony trioxide and metal. and antimony trioxide were produced by one company in The company also operated a smelter and mines in Mexico. Montana by upgrading imported antimony intermediate USAC produced antimony metal for bearings, lead alloys, and products. Secondary antimony was recovered as a component ordnance; antimony oxide as a raw material for flame retardants; of lead alloys from recycled lead-acid batteries at secondary and sodium antimonite for glass and other applications. lead smelters. USAC also recycled antimony-containing products that would Reported consumption of primary antimony increased by 10% otherwise be discarded. In 2015, USAC concluded a capacity from that in 2015 primarily owing to increases in consumption expansion project at its smelter in Madero, Mexico, with the for use in metal products (table 2). In 2016, about 31% of the addition of a large furnace and five smaller furnaces to process reported primary antimony used in the United States was in high-grade concentrates. -

40 Common Minerals and Their Uses

40 Common Minerals and Their Uses Aluminum Beryllium The most abundant metal element in Earth’s Used in the nuclear industry and to make light, crust. Aluminum originates as an oxide called but strong alloys used by the aircraft industry. alumina. Bauxite ore is the main source of Beryllium salts are used in fluorescent lamps, aluminum and is imported from Jamaica, Brazil, X-ray tubes and as a deoxidizer in bronze metal- Guinea, Guyana, etc. It’s used in transportation lurgy. It is used in computers, telecommunication (automobiles), packaging, building/construction, and electronics products, aerospace and de- electrical, machinery and other applications. The fense applications, appliances, automotive and U.S. was 52 percent import reliant for aluminum consumer electronics, and medical applications. in 2016. The U.S. was 10 percent import reliant in 2016. Antimony Chromite A native element, antimony metal is extracted The U.S. consumes about 5 percent of world from stibnite ore and other minerals. It is used chromite ore production in various forms of im- as a hardening alloy for lead, especially storage ported materials, such as chromite ore, chromite batteries and cable sheaths. It’s also used in chemicals, chromium ferroalloys, chromium bearing metal, type metal, solder, collapsible metal and stainless steel. It’s used as an alloy in tubes and foil, sheet and pipes and semiconduc- stainless and heat resisting steel products. It’s tor technology. Antimony is used as a flame re- also used in chemical and metallurgical indus- tardant, in fireworks and in antimony salts, which tries (chrome fixtures, etc.). Superalloys require are used in the rubber, chemical and textile chromium. -

Stibnite Historic District AND/OR COMMON Stibnite Mining District ILOCATION STREET& NUMBER U.S

Form No. 10-306 (Rev. 10-74) UN'lTED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THH INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES mill!! 1 INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM iillliilllit FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC Stibnite Historic District AND/OR COMMON Stibnite Mining District ILOCATION STREET& NUMBER U.S. Forest Road 412 N/ANOTFOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Yellow Pine X VICINITY OF First________ STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Idaho 016 Valley 085 CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE X_DISTRICT _PUBLIC _OCCUPIED _AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE X.UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE X-BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS _EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE _SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT N/AT'N PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC N/A- BEING CONSIDERED X-YES: UNRESTRICTED X-'NDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO _MILITARY MOTHER: National _____Forest | AGENCY REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS: inapplicable) Payette National Forest STREET & NUMBER P.O. Box 1026 CITY. TOWN STATE McCall . iiZ& VICINITY OF Idaho 83638 ILOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC. Valley County Courthouse STREET & NUMBER 219 Main Street CITY, TOWN STATE Cascade Idaho 83611 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Idaho State Archeological Survey DATE 1980 —FEDERAL X_STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Idaho State Historical Society CITY. TOWN STATE Boise Idaho CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE -EXCELLENT ^DETERIORATED —UNALTERED K.ORIGINALSITE -GOOD 2LRUINS X.ALTERED —MOVED DATF N/A -FAIR _UNEX POSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Stibnite Historic District is a collection of historic sites associated with tungsten and antimony mining that supplied strategic minerals needed for the U.S. -

STIBNITE-QUARTZ DEPOSITS (MODELS 27D,E and 36C; Bliss and Orris, 1986A-C; Berger, 1993)

STIBNITE-QUARTZ DEPOSITS (MODELS 27d,e and 36c; Bliss and Orris, 1986a-c; Berger, 1993) by Robert R. Seal, II, James D. Bliss, and David L. Campbell SUMMARY OF RELEVANT GEOLOGIC, GEOENVIRONMENTAL, AND GEOPHYSICAL INFORMATION Deposits described in this model are designated "Stibnite-quartz deposits" to describe a group of antimony deposits that share many of the characteristics of simple (vein dominated) antimony deposits (Model 27d; Bliss and Orris, 1986a,b), disseminated antimony deposits (Model 27e; Bliss and Orris, 1986c), and gold-antimony deposits (Model 36c; Berger, 1993), but have features that distinguish them from these models. The Lake George deposit (New Brunswick, Canada) is included in the "stibnite-quartz deposit" geoenvironmental model. However, it was also included by Bliss and Orris (1986a) in their simple antimony (27d) and disseminated antimony (27e) models. The most significant distinction between stibnite-quartz deposits and simple antimony and disseminated antimony models is the lack of an association with volcanic rocks and a minimal association with intrusive rocks. Stibnite-quartz deposits are hosted dominantly by shale, marl, and carbonate rocks (±quartzite and granite) or their low-grade metamorphic (greenschist facies) equivalents, whereas many gold-antimony deposits are associated with mafic and ultramafic metavolcanic rocks. Stibnite-quartz deposits are most similar to those gold-antimony deposits that are hosted by Late Proterozoic turbiditic black shale, siltstone, sandstone, and carbonate rocks; however, gold grades of the stibnite-quartz deposits are distinctly lower than those of the gold-antimony deposits. Gold has been identified in the Lake George (New Brunswick, Canada) stibnite-quartz deposit, but it is present in a minor vein set (Seal and others, 1988) and has not been extracted during mining and milling of the ore.