Section Training

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Waste Minimization & Recycling in Singapore

2016 World Waste to Energy City Summit Sustainable Singapore – Waste Management and Waste-to-Energy in a global city 11 May 2016 Kan Kok Wah Chief Engineer Waste & Resource Management Department National Environment Agency Singapore Outline 1. Singapore’s Solid Waste Management System 2. Key Challenges & Opportunities 3. Waste-to-Energy (WTE) and Resource Recovery 4. Next Generation WTE plants 2 Singapore Country and a City-State Small Land Area 719.1 km2 Dense Urban Setting 5.54 mil population Limited Natural Resources 3 From Past to Present From Direct landfilling From 1st waste-to-energy plant Ulu Pandan (1979) Lim Chu Kang Choa Chu Kang Tuas (1986) Tuas South (2000) Lorong Halus …to Offshore landfill Senoko (1992) Keppel Seghers (2009) 4 Overview of Solid Waste Management System Non-Incinerable Waste Collection Landfill 516 t/d Domestic Total Waste Generated 21,023 t/d Residential Trade 2% Incinerable Waste Recyclable Waste 7,886 t/d 12,621 t/d 38% 60% Ash 1,766 t/d Reduce Reuse Total Recycled Waste 12,739 t/d Metals Recovered 61% 118 t/d Industries Businesses Recycling Waste-to-Energy Non-Domestic Electricity 2,702 MWh/d 2015 figures 5 5 Key Challenges – Waste Growth and Land Scarcity Singapore’s waste generation increased about 7 folds over the past 40 years Index At this rate of waste growth… 4.00 New waste-to-energy GDP 7-10 years 3.00 Current Population: 5.54 mil Land Area: 719 km2 Semakau Landfill Population Density : 7,705 per km2 ~2035 2.00 Population 30-35 years New offshore landfill 1.00 Waste Disposal 8,402 tonnes/day (2015) -

Country Report Singapore

Country Report Singapore Natural Disaster Risk Assessment and Area Business Continuity Plan Formulation for Industrial Agglomerated Areas in the ASEAN Region March 2015 AHA CENTRE Japan International Cooperation Agency OYO International Corporation Mitsubishi Research Institute, Inc. CTI Engineering International Co., Ltd. Overview of the Country Basic Information of Singapore 1), 2), 3) National Flag Country Name Long form : Republic of Singapore Short form : Singapore Capital Singapore (city-state) Area (km2) Total: 716 Land: 700 Inland Water: 16 Population 5,399,200 Population density(people/ km2 of land area) 7,713 Population growth (annual %) 1.6 Urban population (% of total) 100 Languages Malay (National/Official language), English, Chinese, Tamil (Official languages) Ethnic Groups Chinese 74%, Malay 13%, Indian 9%, Others 3% Religions Buddhism, Islam, Christianity, Daoism, Hinduism GDP (current US$) (billion) 298 GNI per capita, PPP (current international $) 76,850 GDP growth (annual %) 3.9 Agriculture, value added (% of GDP) +0 Industry, value added (% of GDP) 25 Services, etc., value added (% of GDP) 75 Brief Description Singapore is a city-state consisting of Singapore Island, which is located close to the southern edge of the Malay Peninsula, and 62 other smaller outlying islands. Singapore is ranked as the second most densely populated country in the world, after Monaco. With four languages being used as official languages, the country itself is a competitive business district. Therefore, there are many residents other than Singaporean living in the country. Singapore is one of the founding members of ASEAN (founded on August 8, 1967), and the leading economy in ASEAN. Cooperation with ASEAN countries is a basic diplomatic policy of Singapore. -

Ministry of Health List of Approved Offsite Providers for Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) Tests for COVID-19

Ministry of Health List of Approved Offsite Providers for Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) Tests for COVID-19 List updated as at 26 February 2021. Service Provider Name of Location Address Service Provided Partnering Lab Acumed Offsite PCR Swab Parkway Laboratory Services Shangri-La Hotel 22 Orange Grove Rd, Singapore 258350 Medical and Serology Ltd Group Parkway Laboratory Services St Engineering Marine 16 Benoi Road S(629889) Ltd Quest Laboratories Pte Ltd Offsite PCR Swab Ally Health Q Squared Solutions Bukit Batok North N4 432A Bukit Batok West Avenue 8, S(651432) and Serology (In Laboratory Partnership C882 6A Raeburn Park, S(088703) National Public Health With Jaga- Laboratory Me) Sands Expo And Convention Centre 10 Bayfront Ave, Singapore 018956 Parkway Laboratory Services 1 Harbour Front Ave Level 2 Keppel Bay Tower, Singapore Ltd Keppel Office 098632 Offsite PCR Swab 40 Scotts Road, #22-01 Environment Building, Singapore PUB Office 228231 The Istana 35 Orchard Rd, Singapore 238823 One Marina Boulevard 1 Marina Boulevard S018989 Rasa Sentosa Singapore 101 Siloso Road S098970 Bethesda MWOC @ Ponggol Northshore 501A Ponggol Way, Singapore 828646 Offsite PCR Swab Innovative Diagnostics Pte Ltd Medical MWOC @ CCK 10A Lorong Bistari, Singapore 688186 And Serology Centre MWOC @ Eunos 10A Eunos Road 1, Singapore 408523 Services MWOC @ Tengah A 1A Tengah Road, Singapore 698813 Page 1 of 85 MWOC @ Tengah B; 3A Tengah Road, Singapore 698814 Parkway Laboratory Services Hotel Chancellor 28 Cavenagh / Orchard Road, Singapore 229635 Limited -

From Tales to Legends: Discover Singapore Stories a Floral Tribute to Singapore's Stories

Appendix II From Tales to Legends: Discover Singapore Stories A floral tribute to Singapore's stories Amidst a sea of orchids, the mythical Merlion battles a 10-metre-high “wave” and saves a fishing village from nature’s wrath. Against the backdrop of an undulating green wall, a sorcerer’s evil plan and the mystery of Bukit Timah Hill unfolds. Hidden in a secret garden is the legend of Radin Mas and the enchanting story of a filial princess. In celebration of Singapore’s golden jubilee, 10 local folklore are brought to life through the creative use of orchids and other flowers in “Singapore Stories” – a SG50-commemorative floral display in the Flower Dome at Gardens by the Bay. Designed by award-winning Singaporean landscape architect, Damian Tang, and featuring more than 8,000 orchid plants and flowers, the colourful floral showcase recollects the many tales and legends that surround this city-island. Come discover the stories behind Tanjong Pagar, Redhill, Sisters’ Island, Pulau Ubin, Kusu Island, Sang Nila Utama and the Singapore Stone – as told through the language of plants. Along the way, take a walk down memory lane with scenes from the past that pay tribute to the unsung heroes who helped to build this nation. Date: Friday, 31 July 2015 to Sunday, 13 September 2015 Time: 9am – 9pm* Location: Flower Dome Details: Admission charge to the Flower Dome applies * Extended until 10pm on National Day (9 August) About Damian Tang Damian Tang is a multiple award-winning landscape architect with local and international titles to his name. -

National Day Awards 2019

1 NATIONAL DAY AWARDS 2019 THE ORDER OF TEMASEK (WITH DISTINCTION) [Darjah Utama Temasek (Dengan Kepujian)] Name Designation 1 Mr J Y Pillay Former Chairman, Council of Presidential Advisers 1 2 THE ORDER OF NILA UTAMA (WITH HIGH DISTINCTION) [Darjah Utama Nila Utama (Dengan Kepujian Tinggi)] Name Designation 1 Mr Lim Chee Onn Member, Council of Presidential Advisers 林子安 2 3 THE DISTINGUISHED SERVICE ORDER [Darjah Utama Bakti Cemerlang] Name Designation 1 Mr Ang Kong Hua Chairman, Sembcorp Industries Ltd 洪光华 Chairman, GIC Investment Board 2 Mr Chiang Chie Foo Chairman, CPF Board 郑子富 Chairman, PUB 3 Dr Gerard Ee Hock Kim Chairman, Charities Council 余福金 3 4 THE MERITORIOUS SERVICE MEDAL [Pingat Jasa Gemilang] Name Designation 1 Ms Ho Peng Advisor and Former Director-General of 何品 Education 2 Mr Yatiman Yusof Chairman, Malay Language Council Board of Advisors 4 5 THE PUBLIC SERVICE STAR (BAR) [Bintang Bakti Masyarakat (Lintang)] Name Designation Chua Chu Kang GRC 1 Mr Low Beng Tin, BBM Honorary Chairman, Nanyang CCC 刘明镇 East Coast GRC 2 Mr Koh Tong Seng, BBM, P Kepujian Chairman, Changi Simei CCC 许中正 Jalan Besar GRC 3 Mr Tony Phua, BBM Patron, Whampoa CCC 潘东尼 Nee Soon GRC 4 Mr Lim Chap Huat, BBM Patron, Chong Pang CCC 林捷发 West Coast GRC 5 Mr Ng Soh Kim, BBM Honorary Chairman, Boon Lay CCMC 黄素钦 Bukit Batok SMC 6 Mr Peter Yeo Koon Poh, BBM Honorary Chairman, Bukit Batok CCC 杨崐堡 Bukit Panjang SMC 7 Mr Tan Jue Tong, BBM Vice-Chairman, Bukit Panjang C2E 陈维忠 Hougang SMC 8 Mr Lien Wai Poh, BBM Chairman, Hougang CCC 连怀宝 Ministry of Home Affairs -

List of Licensed General Waste Disposal Facilities (Gwdfs) IMPORTANT NOTE: Please Contact the Companies for More Information

List of Licensed General Waste Disposal Facilities (GWDFs) IMPORTANT NOTE: Please contact the companies for more information. Since 1 August 2017, NEA began licensing General Waste Disposal Facilities (GWDFs). A GWDF is defined as a disposal facility which receives, stores, sorts, treats or processes general waste, and includes recycling facilities. Companies can apply for the Licence/Exemption via https://licence1.business.gov.sg. All general waste disposal facilities must obtain their licence or submit an exemption declaration by 31 July 2018. For more information on the GWDF Licence, please visit http://www.nea.gov.sg/energy-waste/waste-management/general-waste-disposal-facility/ Waste Stream Company Facility Address Contacts Ash Paper Plastic Sludge E-Waste Steel Slag Steel C&D waste C&D Refrigerant Scrap Metal Scrap Glass Waste Glass WoodWaste Textile Waste Textile Biomass Waste Biomass Return Concrete Return Used Cooking Oil Cooking Used Spent Copper Slag Spent Copper Mixed Recyclables Mixed Horticultural Waste Horticultural Tyre/RubberWaste Used CoffeeCapsules Used Refrigerant Cylinder/Tank Refrigerant Waste generated from the from generated Waste manufacture of electrical and manufactureofelectrical Industrial and Commercial Waste andCommercial Industrial 800 Super Waste Management 6 Tuas South Street 7 636892 [email protected]; Y Pte Ltd 62 Sungei Kadut Street 1 Sungei [email protected]; 85 Auto Trading Y Kadut Industrial Estate 729363 [email protected]; 21 Tuas West Avenue #03-01 A~Star Plastics Pte Ltd [email protected] -

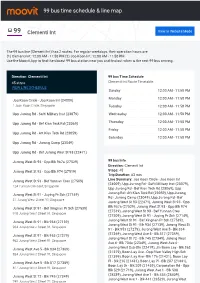

99 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

99 bus time schedule & line map 99 Clementi Int View In Website Mode The 99 bus line (Clementi Int) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Clementi Int: 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM (2) Joo Koon Int: 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 99 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 99 bus arriving. Direction: Clementi Int 99 bus Time Schedule 45 stops Clementi Int Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM Monday 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM Joo Koon Circle - Joo Koon Int (24009) 1 Joon Koon Circle, Singapore Tuesday 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM Upp Jurong Rd - Safti Military Inst (23079) Wednesday 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM Upp Jurong Rd - Bef Kian Teck Rd (23069) Thursday 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM Friday 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM Upp Jurong Rd - Aft Kian Teck Rd (23059) Saturday 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM Upp Jurong Rd - Jurong Camp (23049) Upp Jurong Rd - Bef Jurong West St 93 (22471) Jurong West St 93 - Opp Blk 987a (27529) 99 bus Info Direction: Clementi Int Jurong West St 93 - Opp Blk 974 (27519) Stops: 45 Trip Duration: 63 min Jurong West St 93 - Bef Yunnan Cres (27509) Line Summary: Joo Koon Circle - Joo Koon Int (24009), Upp Jurong Rd - Safti Military Inst (23079), 124 Yunnan Crescent, Singapore Upp Jurong Rd - Bef Kian Teck Rd (23069), Upp Jurong Rd - Aft Kian Teck Rd (23059), Upp Jurong Jurong West St 91 - Juying Pr Sch (27149) Rd - Jurong Camp (23049), Upp Jurong Rd - Bef 31 Jurong West Street 91, Singapore Jurong West St 93 (22471), Jurong West St 93 - Opp Blk 987a (27529), Jurong West St 93 - Opp Blk -

USE THIS Singapore Scenic Driving Map OCT 30

Morning drive 77 Early afternoon drive 56 Industrial Jurong and Exploring the central catchment area km scenic Kranji countryside km The Great START POINT 7 Rie Range Road 1 Seah Im carpark • The little-known stretch • One landmark is the next to hawker centre off Dunearn Road cuts into the Bukit Timah Satellite • The prominent Singapore Drive Bukit Timah Nature Reserve. Earth Station. landmark in Seah Im Road is the 83m tower built in 1974 as part of the cable car system. Who says Singapore is too small for a good road trip? • Seah Im Hawker Centre Follow Straits Times assistant news editor Toh Yong Chuan and a bus terminal were on a 200km drive around the island to discover built in the 1980s, and they were popular meeting spots little-known spots and special lookout points. for those heading towards Sentosa by ferry. 8 Old Upper Thomson 2 “99” turns at Road Grand Prix circuit South Buona Vista Road 1961-1973 • The famously winding • Between 1961 and 1973, road runs downhill from this was the street circuit National University of for the Malaysian Grand Prix Singapore to West Coast and Singapore Grand Prix. Highway. • The 4.8km circuit has • The number of turns is catchy names like Thomson wildly exaggerated. There Mile and Devil’s Bend. are 11, not 99, turns. • A 3km stretch is now • The road is known as a one-way street to an accident hot spot and accommodate a park the 40kmh speed limit is connector. lower than that on most roads in Singapore. 9 Casuarina tree at 10 Soek Seng 1954 Bicycle Cafe Upper Seletar Reservoir • Diners can enjoy views of the • This lone casuarina tree Seletar Airport runway and parked at Upper Seletar Reservoir planes from the eatery. -

Submerged Outlet Drain Once in Three Month Desilting and Flushing

Submerged Outlet Drain Once in Three Month Desilting and Flushing Drain S/No Location Frequency Length 4.5m wide U-drain from the culvert at Jurong Road near Track 22 to the 1 outlet of the culvert at PIE (including the culverts across Jurong Road and 65 1st week of the month across PIE) 9m/12m wide Sungei Jurong subsidiary drain running along PIE from L/P 2 380 1st week of the month 606 to L/P 586 1.5m wide U-drain/covered drain from the junction of Yuan Ching Road/ 3 790 2nd week of the month Jalan Ahmad 13m wide U-drain from Jurong West Street 65 to Major Drain MJ 14 near 4 450 2nd week of the month Blk 664A 15m wide Sg Jurong subsidiary drain from L/P 586 at PIE to Sg Jurong 5 950 2nd week of the month including one 6 10m wide Sg Jurong subsidiary drain from L/P 534 at PIE to Sg Jurong 1180 3rd week of the month Along Boon Lay Way opposite Jurong West Street 61 to Jalan Boon Lay 7 1300 4th week of the month and at Enterprise Road 8 Blk 664A Jurong West Street 64 to MJ13 650 4th week of the month 9 Sungei Lanchar (From Jalan Boon Lay to Jurong Lake 1,600 5th week of the month 10 Sungei Jurong (From Ayer Rajah Expressway to Jurong Lake) 1070 6th week of the month 3.0m wide Outlet drain from culvert at Teban Garden Road running along 11 Jurong Town Hall Road and West Coast Road to Sg Pandan opposite Block 650 7th week of the month 408 30.0m wide Sg Pandan from the branch connection to the downstream Boon 12 350 7th week of the month Lay Way to Sg Ulu Pandan 13 Sungei Pandan (from confluence of Sg Pandan to West Coast Road) 600 7th week -

Media Release to News Editors SAFRA CHOA CHU KANG TO

Media Release To News Editors SAFRA CHOA CHU KANG TO OFFER TRAMPOLINE PARK, INDOOR CLIMBING FACILITY, INTEGRATED ENTERTAINMENT HUB AND ECO-FRIENDLY FEATURES Expected to draw over 1.4 million visitors annually Come 2022, over 90,000 Singapore Armed Forces (SAF) National Servicemen and their families residing within the north-western part of Singapore, will have convenient access to a wide range of unique facilities for fitness and recreation when SAFRA’s seventh club is built within Choa Chu Kang Park. SAFRA Choa Chu Kang is part of the government’s continuing efforts to recognise NSmen for their contributions towards national defence and is expected to draw over 1.4 million visitors annually. The Groundbreaking Ceremony of the club was graced by Minister for Health and Advisor to Chua Chu Kang Group Representative Constituency Grassroots Organisations Mr Gan Kim Yong. The event was also graced by Senior Minister of State for Defence and President of SAFRA Dr Mohamad Maliki Bin Osman. Unique Fitness Facilities Themed as a ‘Fitness Oasis’, SAFRA Choa Chu Kang will feature many firsts among SAFRA clubs and provide NSmen and their families with many avenues to keep fit. It will be the first among SAFRA clubhouses to house a trampoline park. The trampoline park will be operated by Katapult, and will have an obstacle course section and offer fun-filled trampoline aerobics programmes for both adults and children. The club will also be the first among SAFRA clubhouses to have a sheltered swimming pool, aquagym, sheltered futsal court and sky running track, for NSmen to enjoy, rain or shine. -

SAFTI MI 50Th Anniversary

TABLE OF CONTENTS Message by Minister for Defence 02 TOWARDS EXCELLENCE – Our Journey 06 Foreword by Chief of Defence Force 04 TO LEAD – Our Command Schools 30 Specialist and Warrant Officer Institute 32 Officer Cadet School 54 Preface by Commandant 05 SAF Advanced Schools 82 SAFTI Military Institute Goh Keng Swee Command and Staff College 94 TO EXCEL – Our Centres of Excellence 108 Institute for Military Learning 110 Centre for Learning Systems 114 Centre for Operational Learning 119 SAF Education Office 123 Centre for Leadership Development 126 TO OVERCOME – Developing Leaders For The Next 50 Years 134 APPENDICES 146 Speeches SAFTI was the key to these ambitious plans because our founding leaders recognised even at the inception of the SAF that good leaders and professional training were key ingredients to raise a professional military capable of defending Singapore. MESSAGE FROM MINISTER FOR DEFENCE To many pioneer SAF regulars, NSmen and indeed the public at large, SAFTI is the birthplace of the SAF. Here, at Pasir Laba Camp, was where all energies were focused to build the foundations of the military of a newly independent Singapore. The Government and Singaporeans knew what was at stake - a strong SAF was needed urgently to defend our sovereignty and maintain our new found independence. The political battles were fought through the enactment of the SAF and Enlistment Acts in Parliament. These seminal acts were critical but they were but the beginning. The real war had to be fought in the community, as Government and its Members of Parliament convinced each family to do their duty and give up their sons for military service. -

New Zealand Defence Minister Calls on Dr Tan

New Zealand Defence Minister Calls on Dr Tan 30 Sep 1998 The New Zealand Minister for Defence, the Honourable Mr Max Bradford, called on the Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Defence, Dr Tony Tan, this morning, 30 Sep 98, at the Ministry of Defence, Gombak Drive. Upon his arrival at MINDEF, Mr Bradford reviewed a Guard-of-Honour. Mr Bradford is here on his introductory visit from 29 Sep to 2 Oct 98. Mr Bradford will call on Acting Prime Minister BG (NS) Lee Hsien Loong, and deliver the second lecture in the Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies (IDSS) "Strategic Challenges of the Asia Pacific" lecture series on 2 Oct 98. On the same day, Mr Bradford will visit the inaugural Ex SINGKIWI, a bilateral exercise between the Republic of Singapore Air Force (RSAF) and the Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF), at Paya Lebar Air Base (PLAB). RNZAF A-4K Skyhawks, and RSAF F-5 Tiger, F-16 Fighting Falcon and A-4SU Super Skyhawk fighter aircraft are conducting a range of air training activities under the exercise from 21 Sep to 2 Oct 98. Whilst at PLAB, he will also be shown the RSAF's Air Combat Manoeuvring Instrumentation (ACMI) system. Mr Bradford's programme includes visits to SAFTI Military Institute, Tuas Naval Base, Headquarters Artillery, Tengah Air Base, and Changi Air Base for the annual Maritime Patrol Aircraft (MPA) Training Affiliation between the RNZAF's P-3K squadron and the RSAF's Fokker 50 squadron. Singapore and New Zealand have a long-standing defence relationship, and this has strengthened significantly in recent years.