NHB Jurong Trail Booklet Cover R5.Ai

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Government Financial Statements for the Financial Year 2020/2021

GOVERNMENT FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE FINANCIAL YEAR 2020/2021 Cmd. 10 of 2021 ________________ Presented to Parliament by Command of The President of the Republic of Singapore. Ordered by Parliament to lie upon the Table: 28/07/2021 ________________ GOVERNMENT FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE FINANCIAL YEAR by OW FOOK CHUEN 2020/2021 Accountant-General, Singapore Copyright © 2021, Accountant-General's Department Mr Lawrence Wong Minister for Finance Singapore In compliance with Regulation 28 of the Financial Regulations (Cap. 109, Rg 1, 1990 Revised Edition), I submit the attached Financial Statements required by section 18 of the Financial Procedure Act (Cap. 109, 2012 Revised Edition) for the financial year 2020/2021. OW FOOK CHUEN Accountant-General Singapore 22 June 2021 REPORT OF THE AUDITOR-GENERAL ON THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS OF THE GOVERNMENT OF SINGAPORE Opinion The Financial Statements of the Government of Singapore for the financial year 2020/2021 set out on pages 1 to 278 have been examined and audited under my direction as required by section 8(1) of the Audit Act (Cap. 17, 1999 Revised Edition). In my opinion, the accompanying financial statements have been prepared, in all material respects, in accordance with Article 147(5) of the Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (1999 Revised Edition) and the Financial Procedure Act (Cap. 109, 2012 Revised Edition). As disclosed in the Explanatory Notes to the Statement of Budget Outturn, the Statement of Budget Outturn, which reports on the budgetary performance of the Government, includes a Net Investment Returns Contribution. This contribution is the amount of investment returns which the Government has taken in for spending, in accordance with the Constitution of the Republic of Singapore. -

Release No.: 43/OCT SPEECH by MR. LIM HNG KIANG, ACTING MINISTER for NATIONAL DEVELOPMENT, at TEE OPENING of the WHAMPOA FLYOVER

Release No.: 43/OCT 14-2/94/10/29 SPEECH BY MR. LIM HNG KIANG, ACTING MINISTER FOR NATIONAL DEVELOPMENT, AT TEE OPENING OF THE WHAMPOAFLYOVER ON SATURDAY, 29 OCTOBER1994 AT 11.30 AN I am happy to be here this morning to officially open the new Whampoa Flyover. The Pan-Island Expressway (PIE) is Singapore's first and longest expressway. To cater for further increases in travel demand, the Public Works Department (PWD) had in 1991 embarked on a $185 million comprehensive programme to upgrade and improve the middle stretch of PIE between Jalan Eunos and BKE. The upgrading works include the widening of the main carriageway, the expansion of the Woodsville, Whampoa and Whitley Flyovers, the building of the new Kim Keat Flyover, and the improvement to the Toa Payoh South Flyover. The interchange of the Pan Island Expressway and the Central Expressway (CTE) is a major intersection of the two expressways. It is also, at present, the most complex in our expressway network in that it is the only one which serves as a four-way junction for intersecting expressways. Elsewhere in Singapore, our expressways have been planned to meet at three-way junctions. PWD has staged the construction of the interchange to meet traffic needs. When the CTE was built in 1983, the first stage of the interchange, allowing for three turning movements, was constructed. Provisions were made in the design for its expansion to take on more turning movements. Five additional turning movements are catered by the complete interchange layout, two of which have been opened as part of the construction works. -

Yamato Transport Branch Postal Code Address TA-Q-BIN Lockers

Yamato Transport Branch Postal Code Address TA-Q-BIN Lockers Location Postal Code Cheers Store Address Opening Hours Headquarters 119936 61 Alexandra Terrace #05-08 Harbour Link Complex Cheers @ AMK Hub 569933 No. 53 Ang Mo Kio Ave 3 #01-37, AMK Hub 24 hours TA-Q-BIN Branch Close on Fri and Sat Night 119937 63 Alexandra Terrace #04-01 Harbour Link Complex Cheers @ CPF Building 068897 79 Robinson Road CPF Building #01-02 (Parcel Collection) from 11pm to 7am TA-Q-BIN Call Centre 119936 61 Alexandra Terrace #05-08 Harbour Link Complex Cheers @ Toa Payoh Lorong 1 310109 Block 109 #01-310 Toa Payoh Lorong 1 24 hours Takashimaya Shopping Centre,391 Orchard Rd, #B2-201/8B Fairpricexpress Satellite Office 238873 Operation Hour: 10.00am - 9.30pm every day 228149 1 Sophia Road #01-18, Peace Centre 24 hours @ Peace Centre (Subject to Takashimaya operating hours) Cheers @ Seng Kang Air Freight Office 819834 7 Airline Rd #01-14/15, Cargo Agent Building E 546673 211 Punggol Road 24 hours ESSO Station Fairpricexpress Sea Freight Office 099447 Blk 511 Kampong Bahru Rd #02-05, Keppel Distripark @ Toa Payoh Lorong 2 ESSO 319640 399 Toa Payoh Lorong 2 24 hours Station Fairpricexpress @ Woodlands Logistics & Warehouse 119937 63 Alexandra Terrace #04-01 Harbour Link Complex 739066 50 Woodlands Avenue 1 24 hours Ave 1 ESSO Station Removal Office 119937 63 Alexandra Terrace #04-01 Harbour Link Complex Cheers @ Concourse Skyline 199600 302 Beach Road #01-01 Concourse Skyline 24 hours Cheers @ 810 Hougang Central 530810 BLK 810 Hougang Central #01-214 24 hours -

Fri Sat Sun Public Holidays 1 Central Balestier Access

Alliance Medinet List of Panel Clinics as at November 2017 (APPLICABLE FOR MEDISMART GROUP OUTPATIENT BENEFIT ONLY) OPERATING HOURS - Operating hours are indicative; please call the clinic before visiting to avoid disappointment. - Clinics operating hours may change without prior notice. - Last clinic registration: 30 minutes before closing time, or earlier if the number of patients registered exceeds the capacity that the attending doctor and clinic staff can handle without going way beyond standard clinic operating hours. - Surcharge may be imposed for visit after clinic's last registration. S/N ZONE ESTATE CLINIC NAME BLK ROAD NAME UNIT NO. BUILDING NAME POSTAL CODE PHONE FAX MON - FRI SAT SUN PUBLIC HOLIDAYS CLINIC REMARKS 7.00am - 1.00pm, 7.00am - 1.00pm, 7.00am - 1.00pm, 7.00am - 1.00pm, 1 CENTRAL BALESTIER ACCESS MEDICAL (WHAMPOA) 87 Whampoa Drive #01-869 320087 62521070 67107327 6.00pm - 12.00am 6.00pm - 12.00am 6.00pm - 12.00am 6.00pm - 12.00am Mon, Tue, Thu & Fri: 9.00am - 12.30pm, Formerly located at: 2.00pm - 4.30pm 424 Balestier Road HEAL MEDICAL CENTRE (FORMERLY KNOWN AS 62509550 / Wed: #01-01 2 CENTRAL BALESTIER HEAL BALESTIER CLINIC PTE LTD) 262 Balestier Road #04-01/02 Okio 329714 62512501 63550598 9.00am - 12.30pm 8.30am - 12.30pm Closed Closed Singapore 329810 8.30am - 1.30pm, 3 CENTRAL BALESTIER LIVEWELL MEDICAL FAMILY CLINIC 20 Ah Hood Road #01-08 Zhongshan Mall 329984 69099888 69091448 6.00pm - 9.30pm 6.30pm - 9.30pm 6.30pm - 9.30pm 6.30pm - 9.30pm 8.30am - 12.00pm, 2.00pm - 4.30pm, 4 CENTRAL BALESTIER PARIQUA CLINIC 47 Bendemeer Road #01-1463 330047 62921351 62921351 7.00pm - 9.00pm 8.30am - 12.00pm Closed Closed Mon - Thu: 8.30am - 12.30pm, 2.00pm - 4.30pm, 6.00pm - 9.00pm Fri: 8.30am - 12.30pm, 5 CENTRAL BALESTIER PLUSHEALTH MEDICAL CLINIC & SURGERY 89 Whampoa Drive #01-841 320089 62647845 62648520 2.00pm - 4.30pm 9.00am - 1.00pm 9.00am - 1.00pm Closed Change in clinic operating hours. -

Spend S$150 and Above at Aeropostale Store to Purchase Aeropostale Perfume at S$19.90

AEROPOSTALE • Spend S$150 and above at Aeropostale store to purchase Aeropostale perfume at S$19.90 Valid from 1 May till 31 Jul 2014 Available at all Aeropostale retail shops • Citylink Mall • ION Orchard • Ngee Ann City • Bugis+ Mall AUDIO HOUSE • 59% OFF PHILIPS 46” 3D Ultra Slim Smart LED TV ( AMBILIGHT SERIES) @ only S$899 (U.P S$2,199) • Inclusive of 2 pairs of 3D glasses • Comes with FREE delivery and wall mounting installation • 3 years local warranty Valid from 1 May till 31 Jul 2014 • The Offer is inclusive of any other applicable taxes, surcharges or fees • Other terms and conditions apply. Available outlets: • Audio House Liang Court & Bendemeer 177 River Valley Road #04-01/15, Liang Court Shopping Centre • 72 Bendemeer Road #01-20/21/22 LUZERNE • Limited to 1 purchase per Cardholder CHALONE • Present your BOC Credit Cards and receive FREE S$10 Chalone Lingerie voucher & Bra Protective Hanger (no min. purchase required) One FREE gift per Cardholder • Offer is valid while stocks last • Terms and conditions on lingerie voucher applies • FREE set of assorted Chalone vouchers (worth S$70) with purchase of S$150 and above Valid from 1 May till 31 Jul 2014 • One FREE set of assorted vouchers per Cardholder • Offer is valid while stocks last • Terms and conditions on voucher applies CITIGEMS • Additional 10% OFF Valid from 1 May till 31 Jul 2014 • Applicable on all jewellery including selected discounted items except Rosella©, Best Buys, 999 Gold and standard chains DICKSON WATCH & JEWELLERY • Additional 15% OFF Baume & Mercier watches Valid from 1 May till 31 Jul 2014 Available outlets: Wisma Atria • Knightsbridge • FREE Dunhill Card Case with any purchase of Baume & Mercier watches Valid till 28 Feb 2015 • Offer is valid while stocks last • Dickson Watch & Jewellery reserves the right to change the gift item without prior notice Available at all Dickson Watch & Jewellery outlets CROCODILE • Additional 10% OFF sale items (min. -

List of 106 Recycling Points for Clean up South West! 2021 BUKIT

List of 106 Recycling Points for Clean Up South West! 2021 BUKIT BATOK SMC Recycling Point Address 1 Bukit Batok Community Club Bukit Batok CC 21 Bukit Batok Central Singapore 659959 Collection date & time: 1) Saturday, 16 Jan 2021, 11.00am to 2.00pm 2) Sunday, 17 Jan 2021, 11.00am to 2.00pm 2 Bukit Batok Zone 2 RC Bukit Batok Zone 2 RC Blk 104 Bukit Batok Central #01-283 Singapore 650104 Collection date: Saturday, 16 Jan 2021 Collection time: 9.00am to 1.00pm CHUA CHU KANG GRC Recycling Point Address 3 Brickland Arcade RN Brickland Arcade RN Blk 251 Choa Chu Kang Avenue 2 #01-290 Singapore 680251 Collection date: Saturday, 16 Jan 2021 Collection time: 9.00am to 6.00pm 4 Bukit Gombak Goodview Garden RC Bukit Gombak Goodview Garden RC Blk 387 Bukit Batok West Ave 5 #01-382 Singapore 650387 Collection date: Saturday, 23 Jan 2021 Collection time: 9.00am to 1.00pm 5 Bukit Gombak Guilin RC Bukit Gombak Guilin RC Blk 536 Bukit Batok Street 52 #01-667 Singapore 650536 Collection date: Saturday, 23 Jan 2021 Collection time: 9.00am to 1.00pm 6 Bukit Gombak Hillgrove RC Bukit Gombak Hillgrove RC Blk 510 Bukit Batok Street 52 #01-13 Singapore 650510 Collection date: Sunday, 23 Jan 2021 Collection time: 9.00am to 1.00pm 7 Bukit Gombak Hillview Garden NC Bukit Gombak Hillview Garden NC Chu Yen Playground, Chu Yen Street Singapore 669814 Collection date & time: 1) Saturday, 16 Jan 2021, 9.00am to 12.00pm 2) Tuesday, 19 Jan 2021, 6.00pm to 9.00pm 3) Saturday, 23 Jan 2021, 9.00am to 12.00pm 4) Saturday, 30 Jan 2021, 9.00am to 12.00pm 8 Bukit Gombak Hillview -

Insider People · Places · Events · Dining · Nightlife

APRIL · MAY · JUNE SINGAPORE INSIDER PEOPLE · PLACES · EVENTS · DINING · NIGHTLIFE INSIDE: KATONG-JOO CHIAT HOT TABLES CITY MUST-DOS AND MUCH MORE Ready, set, shop! Shopping is one of Singapore’s national pastimes, and you couldn’t have picked a better time to be here in this amazing city if you’re looking to nab some great deals. Score the latest Spring/Summer goods at the annual Fashion Steps Out festival; discover emerging local and regional designers at trade fair Blueprint; or shop up a storm when The Great Singapore Sale (3 June to 14 August) rolls around. At some point, you’ll want to leave the shops and malls for authentic local experiences in Singapore. Well, that’s where we come in – we’ve curated the best and latest of the city in this nifty booklet to make sure you’ll never want to leave town. Whether you have a week to deep dive or a weekend to scratch the surface, you’ll discover Singapore’s secrets at every turn. There are rich cultural experiences, stylish bars, innovative restaurants, authentic local hawkers, incredible landscapes and so much more. Inside, you’ll find a heap of handy guides – from neighbourhood trails to the best eats, drinks and events in Singapore – to help you make the best of your visit to this sunny island. And these aren’t just our top picks: we’ve asked some of the city’s tastemakers and experts to share their favourite haunts (and then some), so you’ll never have a dull moment exploring this beautiful city we call home. -

Caring for Our People: 50 Years of Healthcare in Singapore

Caring for our People Prime Minister’s Message Good health is important for individuals, for families, and for our society. It is the foundation for our people’s vitality and optimism, and a reflection of our nation’s prosperity and success. A healthy community is also a happy one. Singapore has developed our own system for providing quality healthcare to all. Learning from other countries and taking advantage of a young population, we invested in preventive health, new healthcare facilities and developing our healthcare workforce. We designed a unique financing system, where individuals receive state subsidies for public healthcare but at the same time can draw upon the 3Ms – Medisave, MediShield and Medifund – to pay for their healthcare needs. As responsible members of society, each of us has to save for our own healthcare needs, pay our share of the cost, and make good and sensible decisions about using healthcare services. Our healthcare outcomes are among the best in the world. Average life expectancy is now 83 years, compared with 65 years in 1965. The infant mortality rate is 2 per 1,000 live births, down from 26 per 1,000 live births 50 years ago. This book is dedicated to all those in the Government policies have adapted to the times. We started by focusing on sanitation and public health and went on healthcare sector who laid the foundations to develop primary, secondary and tertiary health services. In recent years, we have enhanced government subsidies of a healthy nation in the years gone by, substantially to ensure that healthcare remains affordable. -

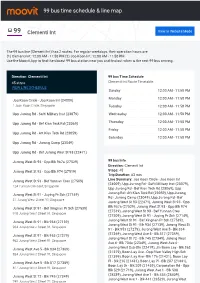

99 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

99 bus time schedule & line map 99 Clementi Int View In Website Mode The 99 bus line (Clementi Int) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Clementi Int: 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM (2) Joo Koon Int: 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 99 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 99 bus arriving. Direction: Clementi Int 99 bus Time Schedule 45 stops Clementi Int Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM Monday 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM Joo Koon Circle - Joo Koon Int (24009) 1 Joon Koon Circle, Singapore Tuesday 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM Upp Jurong Rd - Safti Military Inst (23079) Wednesday 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM Upp Jurong Rd - Bef Kian Teck Rd (23069) Thursday 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM Friday 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM Upp Jurong Rd - Aft Kian Teck Rd (23059) Saturday 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM Upp Jurong Rd - Jurong Camp (23049) Upp Jurong Rd - Bef Jurong West St 93 (22471) Jurong West St 93 - Opp Blk 987a (27529) 99 bus Info Direction: Clementi Int Jurong West St 93 - Opp Blk 974 (27519) Stops: 45 Trip Duration: 63 min Jurong West St 93 - Bef Yunnan Cres (27509) Line Summary: Joo Koon Circle - Joo Koon Int (24009), Upp Jurong Rd - Safti Military Inst (23079), 124 Yunnan Crescent, Singapore Upp Jurong Rd - Bef Kian Teck Rd (23069), Upp Jurong Rd - Aft Kian Teck Rd (23059), Upp Jurong Jurong West St 91 - Juying Pr Sch (27149) Rd - Jurong Camp (23049), Upp Jurong Rd - Bef 31 Jurong West Street 91, Singapore Jurong West St 93 (22471), Jurong West St 93 - Opp Blk 987a (27529), Jurong West St 93 - Opp Blk -

Mr Samuel Kuan)

CONSULTING WORK EXPERIENCES OF THE PRINCIPAL ENGINEER (MR SAMUEL KUAN) No. PE services Project Month/Year 1 Temporary design for Earth Retaining Stabilising Proposed New Erection of 10 Units 2-storey with Jun-13 Structure works attic & Swimming Pool Detached Dwelling House and 30 Units 3-storey with attic and swimming pool semi-detached house with substation at 16 Chestnut Avenue. 2 Temporary design for structural works and Earth Proposed A&A to existing substation (Involving Jul-13 Retaining Stabilising Structure works new erection of a 230KV substation & ancillary facilities) at Upper Jurong Road 3 Temporary design for structural works and Earth Proposed Public Housing Development Jul -13 to Jul Retaining Stabilising Structure works Comprising 3 Blocks of 26/28/30-Storey 16 Residential Building (Total: 808 Units) 1 Block of Part 6 Part 5-Storey Multi-Storey Carpark with Commercial & Community Facilities on the 1st storey & ESS & Ancillary Facilities at Upper Boon Keng Road/ Lor 1 Geylang (Kallang Whampoa C23B) 4 Temporary works design for Geotechnical and Earth C921 Rochor & Little India for Downtown line Aug-13 Retaining Stabilising Structure works 5 Temporary design for structural works and Earth Proposed erection of a 17-storey block of Retaining Stabilising Structure works residential apartments (Total 56 Unit) with a Dec-13 swimming pool and carparks at 235 Balestier Road 6 Temporary design for structural works and Earth Proposed New Erection of a 3-storey Indoor Retaining Stabilising Structure works include Railing Sports Hall -

Submerged Outlet Drain Once in Three Month Desilting and Flushing

Submerged Outlet Drain Once in Three Month Desilting and Flushing Drain S/No Location Frequency Length 4.5m wide U-drain from the culvert at Jurong Road near Track 22 to the 1 outlet of the culvert at PIE (including the culverts across Jurong Road and 65 1st week of the month across PIE) 9m/12m wide Sungei Jurong subsidiary drain running along PIE from L/P 2 380 1st week of the month 606 to L/P 586 1.5m wide U-drain/covered drain from the junction of Yuan Ching Road/ 3 790 2nd week of the month Jalan Ahmad 13m wide U-drain from Jurong West Street 65 to Major Drain MJ 14 near 4 450 2nd week of the month Blk 664A 15m wide Sg Jurong subsidiary drain from L/P 586 at PIE to Sg Jurong 5 950 2nd week of the month including one 6 10m wide Sg Jurong subsidiary drain from L/P 534 at PIE to Sg Jurong 1180 3rd week of the month Along Boon Lay Way opposite Jurong West Street 61 to Jalan Boon Lay 7 1300 4th week of the month and at Enterprise Road 8 Blk 664A Jurong West Street 64 to MJ13 650 4th week of the month 9 Sungei Lanchar (From Jalan Boon Lay to Jurong Lake 1,600 5th week of the month 10 Sungei Jurong (From Ayer Rajah Expressway to Jurong Lake) 1070 6th week of the month 3.0m wide Outlet drain from culvert at Teban Garden Road running along 11 Jurong Town Hall Road and West Coast Road to Sg Pandan opposite Block 650 7th week of the month 408 30.0m wide Sg Pandan from the branch connection to the downstream Boon 12 350 7th week of the month Lay Way to Sg Ulu Pandan 13 Sungei Pandan (from confluence of Sg Pandan to West Coast Road) 600 7th week -

To View Old Chang Kee Operating Hours

Outlet Contact S/N Outlet Outlet Address New Timing Code No. 313 @ Somerset, Orchard Road, #B3-24, (Mon-Fri) 7am - 9pm (BF) 1 313 313 Somerset 6509 4573 Singapore 238895 (Sat/Sun/PH) 10am - 9pm Aljunied MRT Station, 81 Geylang Lorong (Mon-Sat) 7am - 9pm 2 ALJ Aljunied MRT 6518 3534 25, #01-13, Singapore 388310 (Sun/PH) 10am - 9pm 53 Ang Mo Kio Ave 3, #01-32 Ang Mo Kio (Mon-Sat) 7am - 9pm (BF) 3 AMK AMK Hub 6483 0714 Hub, Singapore 569933 (Sun/PH) 10am - 9pm 2450 Ang Mo Kio Ave 8, #01-12/14/15, (Mon-Sat) 7am - 10pm (BF) 4 AMRT AMK MRT 6873 1129 Ang Mo Kio MRT Station, Singapore (Sun/PH) 10am - 10pm 569811 460 Alexandra Road, #02-36 Alexandra (Mon-Fri) 630am - 530pm (BF) 5 ARC Alexandra Retail Centre 6376 0869 Retail Centre, Singapore 119963 (Sat/Sun/PH) Closed 12, Alexandra View, #01-10, Singapore (Mon-Fri) 7am - 10pm (BF) 6 ART ARTRA 6208 9443 158736 (Sat/Sun/PH) 8am - 10pm (BF) 311 New Upper Changi Road, #B2-K4 7 BDM Bedok Mall 6702 4047 (Daily) 10am - 10pm Bedok Mall, Singapore 467360 10, Bukit Batok Central, #01-09 Bukit (Mon-Fri) 630am - 10pm (BF) 8 BBM Bukit Batok MRT 6261 6893 Batok MRT Station, Singapore 659958 (Sat/Sun/PH) 10am - 10pm 230 Victoria St., #B1-13 Bugis Junction, 9 BJ Bugis Junction 6835 9461 (Daily) 11am - 9pm (No BF) Singapore 188024 166 Bukit Merah Central, #02-3531, (Mon-Sat) 630am - 9pm (BF) 10 BM Bukit Merah 6274 9646 Singapore 150166 (Sun/PH) 9am - 9pm (No BF) 1 Jelebu Road, #01-16 Bukit Panjang 11 BP Bukit Panjang 6465 0756 (Daily) 10am-10pm Plaza, Singapore 677743 65 Airport Boulevard, #B2-51 Singapore 12 CA3 Changi Terminal 3 6546 1230 (Daily) 8am-10pm 819663 Caltex Dunearn , 130 Dunearn Road, 13 XDN Caltex Dunearn 6256 0794 (Daily) 9am - 9pm Singapore 309436 Caltex Jurong West, 21 Jurong West St.